Graphene-Based Ammonia Sensors Functionalised with Sub-Monolayer V2O5: A Comparative Study of Chemical Vapour Deposited and Epitaxial Graphene †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Sensor Material Structure and Composition

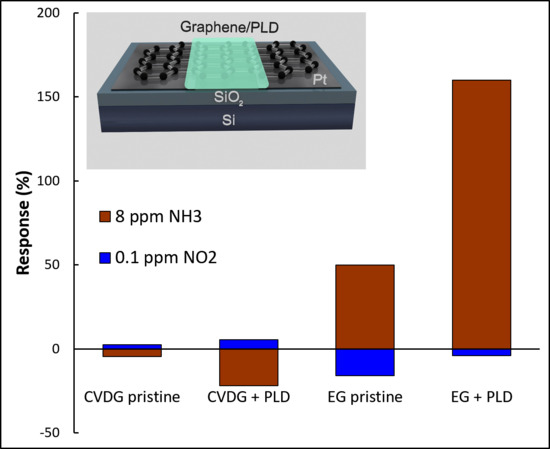

3.2. The Role of Sensor Functionalisation

3.3. Effect of UV Excitation

3.4. Influence of Humidity

3.5. Langmuir Model Fitting of Sensor Response

- (a)

- The transduction coefficients α1 and α2 were both much smaller in case of the CVD graphene sensor, which means either a smaller influence of gas adsorption on the conductivity, or a lower concentration of total active adsorption sites.

- (b)

- The values of corresponding affinity constants b1 and b2 were very close for both types of graphene sensors, which mean that rate constants for adsorption and desorption were similar for both types of functionalised graphene.

3.6. Sensor Selectivity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schedin, F.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Hill, E.W.; Blake, P.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Novoselov, K.S. Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Chen, Y.-B.; Zhou, K.-G.; Liu, C.-H.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, H.-L.; Peng, Y. Improving gas sensing properties of graphene by introducing dopants and defects: A first-principles study. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 185504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.; Yang, G.; Cho, A.; Han, J.W.; Kim, J. Defect-engineered graphene chemical sensors with ultrahigh sensitivity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 14198–14204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, J.; Puglisi, D.; Kang, Y.H.; Yakimova, R.; Lloyd Spetz, A. Adjusting the electronic properties and gas reactivity of epitaxial graphene by thin surface metallization. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2014, 439, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M.; Dong, F.; Yan, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Song, Z.; Chu, W. High efficiency room temperature detection of NO2 gas based on ultrathin metal/graphene devices. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 84082–84089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodu, M.; Berholts, A.; Kahro, T.; Avarmaa, T.; Kasikov, A.; Niilisk, A.; Alles, H.; Jaaniso, R. Highly sensitive NO2 sensors by pulsed laser deposition on graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 113108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Hu, P.A.; Fu, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.; Cao, W.; Yang, B.; Placido, F. A UV light enhanced TiO2/graphene device for oxygen sensing at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 22185–22190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodner, M.; Bahonjic, J.; Mathisen, M.; Gunnarsson, R.; Ekeroth, S.; Helmersson, U.; Ivanov, I.G.; Yakimova, R.; Eriksson, J. Performance tuning of gas sensors based on epitaxial graphene on silicon carbide. Mater. Design 2018, 153, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Wang, K.; Xie, H. Effects of the fabrication temperature and oxygen flux on the properties and nitrogen dioxide sensitivity of the tin oxides-tin/graphene hybrid sensor. J. Mater. Res. 2016, 31, 1993–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, R. (Ed.) Pulsed Laser Deposition of Thin Films: Applications-Led Growth of Functional Materials; Wiley-Interscience (Online Service): Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780470052129. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Paronyan, T.M.; Harutyunyan, A.R. Sub-ppt gas detection with pristine graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 053119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Novikov, S.; Lebedeva, N.; Satrapinski, A.; Walden, J.; Davydov, V.; Lebedev, A. Graphene based sensor for environmental monitoring of NO2. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 236, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, J.; Puglisi, D.; Strandqvist, C.; Gunnarsson, R.; Ekeroth, S.; Ivanov, I.G.; Helmersson, U.; Uvdal, K.; Yakimova, R.; Lloyd Spetz, A. Modified epitaxial graphene on SiC for extremely sensitive and selective gas sensors. Mater. Sci. Forum 2016, 858, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; Hermann, K. Elementary steps of the catalytic NOx reduction with NH3: Cluster studies on reactant adsorption at vanadium oxide substrate. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 094704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodu, M.; Berholts, A.; Kahro, T.; Kook, M.; Ritslaid, P.; Seemen, H.; Avarmaa, T.; Alles, H.; Jaaniso, R. Graphene functionalised by laser-ablated V2O5 for a highly sensitive NH3 sensor. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaaniso, R.; Tan, O.K. (Eds.) Semiconductor Gas Sensors; Woodhead Publ.: Cambridge, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780857098665. [Google Scholar]

- Kodu, M.; Berholts, A.; Kahro, T.; Eriksson, J.; Yakimova, R.; Avarmaa, T.; Renge, I.; Alles, H.; Jaaniso, R. Highly sensitive NH3 sensors using CVD and epitaxial graphene functionalised with vanadium(V) oxide: A comparative study. Proceedings 2018, 2, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakimova, R.; Virojanadara, C.; Gogova, D.; Syväjärvi, M.; Siche, D.; Larsson, K.; Johansson, L.I. Analysis of the formation conditions for large area epitaxial graphene on SiC substrates. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 645–648, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berholts, A.; Kahro, T.; Floren, A.; Alles, H.; Jaaniso, R. Photo-activated oxygen sensitivity of graphene at room temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 162111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, G.R.; Iakimov, T.; Yakimova, R. Epitaxial graphene on SiC: A review of growth and characterization. Crystals 2016, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S.; et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Basko, D.M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.S.; Riedl, C.; Krauss, B.; von Klitzing, K.; Starke, U.; Smet, J.H. Raman spectra of epitaxial graphene on SiC and of epitaxial graphene transferred to SiO2. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 4320–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhafs, C.; Zakharov, A.A.; Ivanov, I.G.; Giannazzo, F.; Eriksson, J.; Stanishev, V.; Kühne, P.; Iakimov, T.; Hofmann, T.; Schubert, M.; et al. Multi-scale investigation of interface properties, stacking order and decoupling of few layer graphene on C-face 4H-SiC. Carbon 2017, 116, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrl, J.; Hundhausen, M.; Emtsev, K.V.; Seyller, T.; Graupner, R.; Ley, L. Raman spectra of epitaxial graphene on SiC (0001). Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 201918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.A.; Puls, C.P.; Staley, N.E.; Stitt, J.P.; Fanton, M.A.; Emtsev, K.V.; Seyller, T.; Liu, Y. Raman topography and strain uniformity of large-area epitaxial graphene. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Pisana, S.; Chakraborty, B.; Piscanec, S.; Saha, S.K.; Waghmare, U.V.; Novoselov, K.S.; Krishnamurthy, H.R.; Geim, A.K.; Ferrari, A.C.; et al. Monitoring dopants by Raman scattering in an electrochemically top-gated graphene transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Li, K.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, C.; Wang, P.; Schwingenschlögl, U.; Yang, W.; et al. Doping monolayer graphene with single atom substitutions. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 14095–14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, L.G.; Jorio, A.; Ferreira, E.H.M.; Stavale, F.; Achete, C.A.; Capaz, R.B.; Moutinho, M.V.O.; Lombardo, A.; Kulmala, T.S.; Ferrari, A.C. Quantifying defects in graphene via Raman spectroscopy at different excitation energies. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3190–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Liu, L.; Berciaud, S.; Yu, Y.J.; Liu, H.; Kim, P.; Flynn, G.W.; Brus, L.E. Atmospheric oxygen binding and hole doping in deformed graphene on a SiO2 substrate. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4944–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Brenner, K.; Murali, R. The influence of atmosphere on electrical transport in graphene. Carbon 2012, 50, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varchon, F.; Feng, R.; Hass, J.; Li, X.; Nguyen, B.N.; Naud, C.; Mallet, P.; Veuillen, J.Y.; Berger, C.; Conrad, E.H.; et al. Electronic structure of epitaxial graphene layers on SiC: Effect of the substrate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emtsev, K.V.; Bostwick, A.; Horn, K.; Jobst, J.; Kellogg, G.L.; Ley, L.; McChesney, J.L.; Ohta, T.; Reshanov, S.A.; Röhrl, J.; et al. Towards wafer-size graphene layers by atmospheric pressure graphitization of silicon carbide. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jaaniso, R.; Kahro, T.; Kozlova, J.; Aarik, J.; Aarik, L.; Alles, H.; Floren, A.; Gerst, A.; Kasikov, A.; Niilisk, A.; et al. Temperature induced inversion of oxygen response in CVD graphene on SiO2. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gui, G.; Huang, Z. Adsorption and oxidation of NH3 over V2O5/AC surface. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 92, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, M.A.; Carrizosa, I.; Odriozola, J.A. NO–NH3 coadsorption on vanadia/titania catalysts: Determination of the reduction degree of vanadium. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2001, 29, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, J.; Bjorklund, R.; Lappalainen, J.; Lloyd Spetz, A. Pulsed laser deposited nanostructured vanadium oxide thin films characterized as ammonia sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 217, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhong, J.; Kyle, J.R.; Penchev, M.; Ozkan, M.; Ozkan, C.S. Molecular absorption and photodesorption in pristine and functionalized large-area graphene layers. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 355701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, R.; Iakimov, T.; Andersson, M.; Hultman, L.; Spetz, A.L.; Yakimova, R. Epitaxially grown graphene based gas sensors for ultra sensitive NO2 detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 155, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, V.; Giusca, C.E.; Lartsev, A.; Martin, N.A.; Cassidy, N.; Myers-Ward, R.L.; Gaskill, D.K.; Kazakova, O. Atmospheric doping effects in epitaxial graphene: Correlation of local and global electrical studies. 2D Materials 2016, 3, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melios, C.; Centeno, A.; Zurutuza, A.; Panchal, V.; Giusca, C.E.; Spencer, S.; Silva, S.R.P.; Kazakova, O. Effects of humidity on the electronic properties of graphene prepared by chemical vapour deposition. Carbon 2016, 103, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.; Hermann, K. Elementary steps of the catalytic NOx reduction with NH3: Cluster studies on reaction paths and energetics at vanadium oxide substrate. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 244701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Han, H.; Gunji, I.; Endou, A.; Ammal, S.S.C.; Kubo, M.; Miyamoto, A. NH3 adsorption on the Brönsted and Lewis acid sites of V2O5 (010): A periodic density functional study. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 4701–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Bai, H. Adsorption behavior of moisture over a vanadia/titania catalyst: A study for the selective catalytic reduction process. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 5983–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lide, D.R. (Ed.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 89th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Shi, T.; Cai, T.; Xu, T.; Sun, L.; Wu, X.; Yu, D. Self healing of defected graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 103107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, R.; Ramasse, Q.M.; Bangert, U.; Novoselov, K.S. Graphene reknits its holes. Nano. Lett. 2012, 12, 3936–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Duan, H.; Xue, J. Mechanism of the defect formation in supported graphene by energetic heavy ion irradiation: The substrate effect. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S. Effect of SiO2 substrate on the irradiation-assisted manipulation of supported graphene: A molecular dynamics study. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 285703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Lu, Y.H.; Cai, Y.Q.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Y.P. Adsorption of gas molecules on transition metal embedded graphene: A search for high-performance graphene-based catalysts and gas sensors. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 385502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzalenchuk, A.; Lara-Avila, S.; Kalaboukhov, A.; Paolillo, S.; Syväjärvi, M.; Yakimova, R.; Kazakova, O.; Janssen, T.J.B.M.; Fal’ko, V.; Kubatkin, S. Towards a quantum resistance standard based on epitaxial graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eriksson, J.; Pearce, R.; Iakimov, T.; Virojanadara, C.; Gogova, D.; Andersson, M.; Syväjärvi, M.; Lloyd Spetz, A.; Yakimova, R. The influence of substrate morphology on thickness uniformity and unintentional doping of epitaxial graphene on SiC. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 241607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, N.; Hayasaka, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Oliveira, O.N.; Lin, L. A review on chemiresistive room temperature gas sensors based on metal oxide nanostructures, graphene and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Ma, T.; Pinna, N.; Zhang, J. Two-dimensional nanostructured materials for gas sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1702168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Neri, G.; Pinna, N. Nanostructured materials for room-temperature gas sensors. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 795–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CVD Graphene on Si/SiO2 | Response | Recovery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line No. | Sample/Conditions | t1 (s) | t2 (s) | Response (%) | t1 (s) | t2 (s) |

| 1 | Pristine, UV, RH20 | 79 | 1887 | −4.7 | 1607 | - |

| 2 | V2O5, no UV, RH20 | 25 | 363 | −18 | 47 | 466 |

| 3 | V2O5, UV, RH0 | 23 | 329 | −16 | 43 | 640 |

| 4 | V2O5, UV, RH20 | 21 | 226 | −22 | 41 | 427 |

| 5 | V2O5, UV, RH50 | 19 | 158 | −25 | 62 | 478 |

| Epitaxial Graphene on SiC | Response | Recovery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line No. | Sample/Conditions | t1 (s) | t2 (s) | Response (%) | t1 (s) | t2 (s) |

| 1 | Pristine, UV, RH20 | 143 | 695 | 50 | 658 | - |

| 2 | V2O5, no UV, RH20 | 16 | 443 | −39 | 56 | 610 |

| 3 | V2O5, UV, RH0 | 23 | 474 | 131 | 41 | 496 |

| 4 | V2O5, UV, RH20 | 19 | 271 | 160 | 30 | 392 |

| 5 | V2O5, UV, RH50 | 26 | 182 | 216 | 57 | 440 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kodu, M.; Berholts, A.; Kahro, T.; Eriksson, J.; Yakimova, R.; Avarmaa, T.; Renge, I.; Alles, H.; Jaaniso, R.

Graphene-Based Ammonia Sensors Functionalised with Sub-Monolayer V2O5: A Comparative Study of Chemical Vapour Deposited and Epitaxial Graphene

Kodu M, Berholts A, Kahro T, Eriksson J, Yakimova R, Avarmaa T, Renge I, Alles H, Jaaniso R.

Graphene-Based Ammonia Sensors Functionalised with Sub-Monolayer V2O5: A Comparative Study of Chemical Vapour Deposited and Epitaxial Graphene

Kodu, Margus, Artjom Berholts, Tauno Kahro, Jens Eriksson, Rositsa Yakimova, Tea Avarmaa, Indrek Renge, Harry Alles, and Raivo Jaaniso.

2019. "Graphene-Based Ammonia Sensors Functionalised with Sub-Monolayer V2O5: A Comparative Study of Chemical Vapour Deposited and Epitaxial Graphene

Kodu, M., Berholts, A., Kahro, T., Eriksson, J., Yakimova, R., Avarmaa, T., Renge, I., Alles, H., & Jaaniso, R.

(2019). Graphene-Based Ammonia Sensors Functionalised with Sub-Monolayer V2O5: A Comparative Study of Chemical Vapour Deposited and Epitaxial Graphene