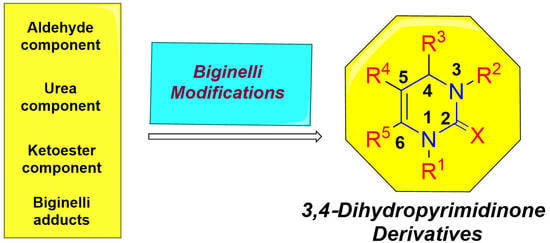

Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidin(thio)one Containing Scaffold: Biginelli-like Reactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Modification of the Urea Counterpart

3. Modification of the Aldehyde Counterpart

4. Modification of the Keto Ester Counterpart

4.1. Diketones as the Keto Ester Component

4.2. Keto Amides as the Keto Ester Component

4.2.1. Barbituric Acid Derivatives

4.2.2. Beta-Ketoamides and Beta-Ketosulfonamides

4.3. Keto Acids as the Keto Ester Component

4.4. Ketones as the Keto Ester Component

4.5. Other Different Substrates as the Keto Ester Component

5. Modification of Two Components

6. Modification of All Components—Alternative Routes to Dihydropyrimidinones

7. Structure Diversification of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidin-2-(1H) (thio)one Derivatives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evans, B.E.; Rittle, K.E.; Bock, M.G.; DiPardo, R.M.; Freidinger, R.M.; Whitter, W.L.; Lundell, G.F.; Veber, D.F.; Anderson, P.S.; Chan, R.S.L.; et al. Methods for drug discovery development of potent, selective, orally effective cholecystokinin antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1988, 31, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patchett, A.A.; Nargund, R.P. Privileged structures—An update. Annual. Rep. Med. Chem. 2000, 35, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Khasimbi, S.; Ali, F.; Manda, K.; Sharma, A.; Chauhan, G.; Wakode, S. Dihydropyrimidinones scaffold as a promising nucleus for synthetic profile and various therapeutic targets: A Review. Curr. Org. Synth. 2021, 18, 270–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeena, T.K.; George, M.; Joseph, L. A systematic review on the recent advances in the pharmacological activities of dihydropyrimidinones. Chem. Res. J. 2019, 4, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Santana-Matos, L.H.; Masson, F.T.; Simeoni, L.A.; Homem-de-Mello, M. Biological activity of dihydropyrimidinone (DHPM) derivatives: A systematic review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Chaudhary, S.; Kumar, K.; Gupta, M.K.; Rawal, R.K. Recent synthetic and medicinal perspectives of dihydropyrimidinones: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 132, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fátima, A.; Braga, T.C.; Neto, L.D.S.; Terra, B.S.; Oliveria, B.G.F.; da Silva, D.L.; Modolo, L.V. A mini-review on Biginelli adducts with notable pharmacological properties. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wan, J.-P.; Pan, Y. Recent advance in the pharmacology of dihydropyrimidinone. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh; Sandhu, J.S. Past, present and future of the Biginelli reaction: A critical perspective. ARKIVOC Online J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2012, 66–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kappe, C.O. Biologically active dihydropyrimidones of the Biginelli-type—A literature survey. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 35, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adole, V.A. Synthetic approaches for the synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones/thiones (Biginelli adducts): A concise review. World. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 9, 1067–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Suma, C.; Amritha, C.K.; Thushara, P.V.; Ananya, V.M. Dihydropyrimidinone derivatives—A review on synthesis and its therapeutic importance. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Res. 2020, 19, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M.; Kaur, A. An update on the synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones using green chemistry approach. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 5, 949–967. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.-P.; Yunyun, L. Synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones and thiones by multicomponent reactions. Strategies beyond the classical Biginelli reaction. Synthesis 2010, 23, 3943–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T.U.; Kapoor, T.M.; Haggarty, S.J.; King, R.W.; Schreiber, S.L.; Mitchison, T.J. Small molecule inhibitor of mitotic spindle bipolarity identified in a phenotype-based screen. Science 1999, 286, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duschinsky, R.; Pleven, E.; Heidelberger, C. Synthesis of potential anticancer agents: 2-fluoroadenosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 4559–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.C.; Nantermet, P.G.; Selnick, H.G.; Glass, K.L.; Rittle, K.E.; Gilbert, K.F.; Steele, T.G.; Homnick, C.F.; Freidinger, R.M.; Ransom, R.W.; et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of dihydropyrimidinone C-5 amides as potent and selective α1A receptor antagonists for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2703–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwal, K.S.; Swanson, B.N.; Unger, S.E.; Floyd, D.M.; Moreland, S.; Hedberg, A.; O´Reilly, B.C. Dihydropyrimidine Calcium Channel Blockers. 3-Carbamoyl-4-aryl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methyl-5-pyrimidinecarboxylic Acid Esters as Orally Effective Antihypertensive Agents. J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, E.W. Experimental chemotherapy of infection with agents of the psittacosis-lymphogranuloma-trachoma group. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1962, 98, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusoff, W.H. Synthesis and biological activities of iododeoxyuridine, and analogue of thymidine. Biochim. Biophis. Acta 1959, 32, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.D.; Kumar, N.V.; Kokke, W.C.; Bean, M.F.; Freyer, A.J.; De Brosse, C.; Mai, S.; Truneh, A.; Faulkner, D.J.; Carte, B.; et al. Novel alkaloids from the sponge Batzella sp.: Inhibitors of HIV gp120-human CD4 binding. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Ren, J.; Esnouf, R.M.; Willcox, B.E.; Jones, E.Y.; Ross, C.; Miyasaka, T.; Walker, R.T.; Tanaka, H.; Stammers, D.K.; et al. Complexes of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with inhibitors of the HEPT series reveal conformational changes relevant to the design of potent non-nucleoside inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 39, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biginelli, P. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1893, 23, 360–416. [Google Scholar]

- Tron, G.C.; Minassi, A.; Appendino, G. Pietro Biginelli: The man behind the reaction. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 5541–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinescu, M. Biginelli Reaction mediated synthesis of antimicrobial pyrimidine derivatives and their therapeutic properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, P.; Nardi, M.; Oliverio, M. Similarity and competition between Biginelli and Hantzsch reactions: An opportunity for modern medicinal chemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 3954–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopda, L.V.; Dave, P.N. Recent advances in homogeneous and heterogeneous catalyst in Biginelli reaction from 2015-19: A concise review. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 5552–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.V.; Chavan, J.U.; Dalal, D.S.; Shinde, V.-S.; Beldar, A.G. Biginelli reaction: Polymer supported catalytic approaches. ACS Comb. Sci. 2019, 21, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumaila, A.M.A.; Al-Thulaia, A.A.N. Mini-review on the synthesis of Biginelli analogs using greener heterogeneous catalysis: Recent strategies with the support or direct catalyzing of inorganic catalysts. Synth. Commun. 2019, 49, 1613–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.M.; Moradi, R.; Mohammadkhani, L.; Moradi, B. Current progress in asymmetric Biginelli reaction: An update. Mol. Divers. 2018, 22, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simurova, N.; Maiboroda, O. Biginelli reaction—An effective method for the synthesis of dihydropyrimidine derivatives. Chem. Het. Comp. 2017, 53, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajaiah, H.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Moorthy, J.N. Biginelli reaction: An overview. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 5135–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.M.; Ghavidel, M.; Heidari, B. Microwave-assisted Biginelli reaction: An old reaction, a new perspective. Curr. Org. Synth. 2016, 13, 569–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, M.M.; Asadi, S.; Lashkariani, B.M. Recent progress in asymmetric Biginelli reaction. Mol. Divers. 2013, 17, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L.-Z.; Chen, X.-H.; Xu, X.-Y. Asymmetric organocatalytic Biginelli reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 8920–8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappe, C.O. 100 years of the Biginelli didydropyrimide synthesis. Tetrahedron 1993, 32, 6937–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, B.C.; Atwal, K.S. Synthesis of substituted 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methyl-2-oxo-5-pyrimidinecarboxyllc acid esters: The Biginelli condensation revisited. Heterocycles 1987, 26, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Atwal, K.S.; O’Reilly, B.C.; Gougoutas, J.Z.; Malley, M.F. Synthesis of substituted 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-methyl thioxo-5-pyrimidinecarboxylic acid esters. Heterocycles 1987, 26, 1189–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwal, K.S.; Rovnyak, G.C.; O’Reilly, B.C.; Schwartz, J. Substituted 1,4-dihydropyrimidines. 3. Synthesis of selectively functionalized 2-hetero-1,4-dihydropyrimidines. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 5898–5907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovnyak, G.C.; Kimball, S.D.; Beyer, B.; Cucinotta, G.; DiMarco, J.D.; Gougoutas, J.; Hedberg, A.; Malley, M.; McCarthy, J.P.; Zhang, R.; et al. Calcium entry blockers and activators: Conformational and structural determinants of dihydropyrimidine calcium channel modulators. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikhale, R.V.; Bhole, R.P.; Khedekar, P.B.; Bhusari, K.P. Synthesis and pharmacological investigation of 3-(substituted-1-phenylethanone)-4-(substituted phenyl)-1, 2, 3,4-tetrahydropyrimidine-5-carboxylates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3645–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, B.; Overman, L. Concise synthesis of guanidine-containing heterocycles using the Biginelli reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 7706–7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, M.J.; Hassan, S.F.; Nisa, R.U.; Ayub, K.; Nadeem, M.S.; Nazir, S.; Ansari, F.L.; Qureshi, N.A.; Rashid, U. Synthesis, in vitro potential and computational studies on 2-amino-1, 4-dihydropyrimidines as multitarget antibacterial ligands. Med. Chem. Res. 2016, 25, 1877–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Jiang, L.-L.; Chen, C.-N.; Yang, G.-F. The first example of a regioselective Biginelli-like reaction based on 3-alkylthio-5-amino-1,2,4-triazole. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2009, 46, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabukhin, S.V.; Plaskon, A.S.; Ostapchuk, E.N.; Volochnyuk, D.M.; Tolmachev, A.A. N-Substituted ureas and thioureas in Biginelli reaction promoted by chlorotrimethylsilane: Convenient synthesis of N1-alkyl-, N1-aryl-, and N1,N3-dialkyl-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-(thi)ones. Synthesis 2007, 3, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, M.S.; Arjun, M.; Sridhar, D.; Srinivas, K.; Raviprasad, T. N-Substituted benzoxazolyl ureas and thioureas in Biginelli reaction promoted by trifluoromethane sulfonic acid: An efficient and convenient synthesis of substituted benzoxazolyl 3,4-dihydropyrimidine (1H)-(thio)-ones. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2009, 20, 909–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajanarendar, E.; Reddy, M.N.; Murthy, K.R.; Reddy, K.G.; Raju, S.; Srinivas, M.; Praveen, B.; Rao, M.S. Synthesis, antimicrobial, and mosquito larvicidal activity of 1-aryl-4-methyl-3,6-bis-(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)-2-thioxo-2,3,6,10b-tetrahydro-1H-pyrimido[5,4-c]quinolin-5-ones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6052–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillo, V.J.; Mansilla, J.; Saá, J.M. Organocatalysis by networks of cooperative hydrogen bonds: Enantioselective direct Mannich addition to preformed arylideneureas. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4312–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninomiya, M.; Garud, D.R.; Koketsu, M. Selenium-containing heterocycles using selenoamides, selenoureas, selenazadienes, and isoselenocyanates. Heterocycles 2010, 81, 2027–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Samdhiana, V.; Bhatiaa, S.K.; Kaura, B. Cell-viability analysis against MCF-7 human breast cell line and antimicrobial evaluation of newly synthesized selenoxopyrimidines. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 55, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauskopf, F.; Truong, K.-N.; Rissanen, K.; Bolm, C. 2,3-Dihydro-1,2,6-thiadiazine 1-oxides by Biginelli-type reactions with sulfonimidamides under mechanochemical conditions. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 2699–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabazzadeh, H.; Saidi, K.; Sheibani, H. Highly efficient conversion of aromatic acylals to 3, 4-dihydropyrimidinones: A new protocol for the Biginelli reaction. Arkivoc 2008, 2008, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stucchi, M.; Lesma, G.; Meneghetti, F.; Rainoldi, G.; Sacchetti, A.; Silvani, A. Organocatalytic asymmetric Biginelli-like reaction involving isatin. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.A.; Dangroo, N.A.; Ara, T. Microwave-assisted tandem Kornblum oxidation and Biginelli reaction for the synthesis of dihydropyrimidones. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12965–12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, S.W.; Patil, N.R.; Samant, S.D. Mg–Al hydrotalcites as the first heterogeneous basic catalysts for the Kornblum oxidation of benzyl halides to benzaldehydes using DMSO. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 1160–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaabani, A.; Bazgir, A.; Teimouri, F. Ammonium chloride-catalyzed one-pot synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-(1H)-ones under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 857–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darehkordi, A.; Hosseini, M.S. Montmorillonite modified as an efficient and environment friendly catalyst for one- pot synthesis of 3, 4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H) ones. Iran. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012, 9, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, M.; Campos, G.; Santos, A.O.; Falcão, A.; Silvestre, S.; Alves, G. Potential antitumoral 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-(1H)-ones: Synthesis, in vitro biological evaluation and QSAR studies. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 84943–84958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, M.; Campos, G.; Santos, A.O.; Falcão, A.; Silvestre, S.; Alves, G. Synthesis, in vitro evaluation and QSAR modelling of potential antitumoral 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-(1H)-thiones. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 5086–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, M.; Sunder-Plassmann, N.; Seiler, J.; Utz, M.; Vernos, I.; Surrey, T.; Giannis, A. Development and biological evaluation of potent and specific inhibitors of mitotic kinesin Eg5. ChemBioChem 2005, 6, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemal, A.L.; Luche, J.L. Lanthanoids in organic synthesis. 6. Reduction of alpha-enones by sodium borohydride in the presence of lanthanoid chlorides: Synthetic and mechanistic aspects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 5454–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwai, M.; Saxena, S.; Khan, M.K.R.; Thukral, S.S. Synthesis of 4-aryl-7,7-dimethyl-1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8-octahydroquinazoline-2-one/thione-5-one derivatives and evaluation as antibacterials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abnous, K.; Barati, B.; Mehri, S.; Farimani, M.R.M.; Alibolandi, M.; Mohammadpour, F.; Ghandadi, M.; Hadizadeh, F. Synthesis and molecular modeling of six novel monastrol analogues: Evaluation of cytotoxicity and kinesin inhibitory activity against HeLa cell line. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 21, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Niralwad, K.S.; Shingate, B.B.; Shingare, M.S. Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis of octahydroquinazolinone derivatives using ammonium metavanadate under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 3616–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badadhe, P.V.; Chate, A.V.; Hingane, D.G.; Mahajan, P.S.; Chavhan, N.M.; Gill, C.H. Microwave-assisted one-pot synthesis of octahydroquinazolinone derivatives catalyzed by thiamine hydrochloride under solvent-free condition. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 2011, 55, 936–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, P.M.; Patel, M.P. Zn(OTf)2-catalyzed three component, one-pot cyclocondensation reaction of some new octahydroquinazolinone derivatives and access their bio-potential. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.C.O.; Correa, J.R.; Rodrigues, M.O.; Alvim, H.G.O.; Guido, B.C.; Gatto, C.C.; Wanderley, K.A.; Fioramonte, M.; Gozzo, F.C.; de Souza, R.O.M.A.; et al. The Biginelli reaction under batch and continuous flow conditions: Catalysis, mechanism and antitumoral activity. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 48506–48515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariwal, J.J.; Malhotra, M.; Molnar, J.; Jain, K.S.; Shah, A.K.; Bariwal, J.B. Synthesis, characterization and anticancer activity of 3-aza-analogues of DP-7. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 4002–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaje, O.C.; Fadeyi, O.O.; Fadeyi, S.A.; Myles, L.E.; Okoro, C.O. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of some fluorinated hexahydropyrimidine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizian, J.; Mohammadi, M.K.; Firuzi, O.; Mirza, B.; Miri, R. Microwave-Assisted Solvent-Free Synthesis of Bis(Dihydropyrimidinone)Benzenes and Evaluation of Their Cytotoxic Activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2010, 75, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Cheng, P.; Lei, N.; Yao, J.; Sheng, C.; Zhuang, C.; Guo, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, G.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel homocamptothecins conjugating with dihydropyrimidine derivatives as potent topoisomerase I inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. 2011, 344, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gijsen, H.J.M.; Berthelot, D.; De Cleyn, M.A.J.; Geuens, I.; Brône, B.; Mercken, M. Tricyclic 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2-thione derivatives as potent TRPA1 antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajitha, G.; Arya, C.G.; Janardhan, B.; Laxmi, S.V.; Ramesh, G.; Kumari, U.S. 3-Aryl/heteryl-5-phenylindeno[1,2-d]thiazolo[3,2-a]pyrimidin-6(5H)-ones: Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial investigation. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 46, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, J.; Gupta, S.K.; Thavaselvam, D.; Agarwal, D.D. Design, synthesis, synergistic antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of 4-aryl substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones of curcumin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2872–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, J.; Gupta, S.K.; Agarwal, D.D. Chitosan: An Efficient Biodegradable and Recyclable Green Catalyst for One-Pot Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidinones of Curcumin in Aqueous Media. Catal. Commun. 2012, 27, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, J.; Gupta, S.K.; Thavaselvam, D.; Agarwal, D.D. Synthesis and pharmacological activity evaluation of curcumin derivatives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Wang, Q.; Tan, T.; Chen, N.; Shuai, M. One-pot synthesis of 13-acetyl-9-methyl-11-oxo(thioxo)-8-oxa-10,12-diazatricyclo[7.3.1.02,7]trideca-2,4,6-trienes under microwave irradiation. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 49, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, B.M.; Shinde, S.K.; Jagdale, A.A.; Jadhav, S.D.; Patil, S.S. Fruit extract of averrhoa bilimbi: A green neoteric micellar medium for isoxazole and biginelli-like synthesis. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2021, 47, 4369–4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.M.; Guido, B.C.; Nobrega, C.C.; Corrêa, J.R.; Silva, R.G.; de Oliveira, H.C.B.; Gomes, A.F.; Gozzo, F.C.; Neto, B.A.D. The Biginelli reaction with an imidazolium–tagged recyclable iron catalyst: Kinetics, mechanism, and antitumoral activity. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4156–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guido, B.C.; Ramos, L.M.; Nolasco, D.O.; Nobrega, C.C.; Andrade, B.Y.G.; Pic-Taylor, A.; Neto, B.A.D.; Corrêa, J.R. Impact of kinesin Eg5 inhibition by 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one derivatives on various breast cancer cell features. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Siddiqui, Z.N.; Khan, T. Unprecedented single-pot protocol for the Synthesis of novel bis-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones using PEG-HClO4 as a biodegradable, highly robust and reusable solid acid green catalyst under solvent-free conditions. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 2526–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davanagere, P.M.; Maiti, B. 1,3-Bis(carboxymethyl)imidazolium chloride as a sustainable, recyclable, and metal-free ionic catalyst for the Biginelli multicomponent reaction in neat condition. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 26035–26047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Emary, T.I.; Abdel-Mohsen, S.A.; Mohamed, S.A. An efficient synthesis and reactions of 5-acetyl-6-methyl-4-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3,4-dihydropyrmidin-2(1H)-thione as potential antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 47, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaabani, A.; Bazgir, A. Microwave-assisted efficient synthesis of spiro-fused heterocycles under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 2575–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaabani, A.; Bazgir, A.; Bijanzadeh, H.R. A reexamination of Biginelli-like multicomponent condensation reaction: One-pot regioselective synthesis of spiro heterobicyclic rings. Mol. Divers. 2004, 8, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, G.; Faramarzi, S.; Asadi, S.; Amanlou, M. Green synthesis and urease inhibitory activity of spiro-pyrimidinethiones/spiro-pyrimidinones-barbituric acid derivatives. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Dabholkar, V.V.; Tripathi, R.D. Synthesis of Biginelli products of thiobarbituric acids and their antimicrobial activity. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2010, 75, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Jain, A.; Joshi, R.; Jain, M. Eco-friendly solventless synthesis of 5-indolylpyrimido[4,5-d]pyrimidinones and their antimicrobial activity. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2011, 32, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rimaz, M.; Khalafy, J.; Mousavi, H. A Green organocatalyzed one-pot protocol for efficient synthesis of new substituted pyrimido[4,5-d]pyrimidinones using a Biginelli-like reaction. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 8185–8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimaz, M.; Khalafy, J.; Mousavi, H.; Bohlooli, S.; Khalili, B. Two different green catalytic systems for one-pot regioselective and chemoselective synthesis of some pyrimido[4,5-d]pyrimidinone derivatives in water. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 3174–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Malik, M.S.; Bajee, S.; Azeeza, S.; Faazil, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Naidu, V.G.M.; Vishnuwardhan, M.V.P.S. Synthesis and biological evaluation of conformationally flexible as well as restricted dimers of monastrol and related dihydropyrimidones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 3274–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadlapalli, R.K.; Chourasia, O.P.; Vemuri, K.; Sritharan, M.; Perali, R.S. Synthesis and in vitro anticancer and antitubercular activity of diarylpyrazole ligated dihydropyrimidines possessing lipophilic carbamoyl group. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2708–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elumalai, K.; Ali, M.A.; Elumalai, M.; Eluri, K.; Srinivasan, S. Design, synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of some novel 3,5-dichloro-2-ethoxy-6-fluoropyridin-4-amine cyclocondensed dihydropyrimidines. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 7, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, K.; Ali, M.A.; Elumalai, M.; Eluri, K.; Srinivasan, S.; Mohanty, S.K. Microwave-assisted synthesis of some novel acetazolamide cyclocondensed 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidines as a potent antimicrobial and cytotoxic agents. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elumalai, K.; Ali, M.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Elumalai, M.; Eluri, K. Antimicrobial and in vitro cytotoxicity of novel sulphanilamide condensed 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidines. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2017, 11, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chikhale, R.; Menghani, S.; Babu, R.; Bansode, R.; Bhargavi, G.; Karodia, N.; Rajasekharan, M.V.; Paradkar, A.; Khedekar, P. Development of selective DprE1 inhibitors: Design, synthesis, crystal structure and antitubercular activity of benzothiazolylpyrimidine-5-carboxamides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 96, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V.; Arumugasamy, K.; Singh, S.K.; Edayadulla, N.; Ramesh, P.; Kamaraj, S.-K. Synthesis, antibacterial studies, and molecular modeling studies of 3,4-dihydropyrimidinone compounds. J. Chem. Biol. 2016, 9, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gein, V.L.; Zamaraeva, T.M.; Fedotov, A.Y.; Balandina, A.V.; Dmitriev, M.V. Synthesis, structure, and antimicrobial activity of N,6-diaryl-4-methyl-2-oxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidine-5-carboxamides. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2016, 86, 2437–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, S.; Kumar, B.P.; Naishima, N.L.; Ashok, T.; Justin, A.; Kumar, M.V.; Chandrashekarappa, R.B.; Raghavendra, N.M.; Kabadi, P.; Adhikary, L. Design, parallel synthesis of Biginelli 1,4-dihydropyrimidines using PTSA as a catalyst, evaluation of anticancer activity and structure activity relationships via 3D QSAR Studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 117, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussolari, J.C.; McDonnell, P.A. A new substrate for the Biginelli cyclocondensation: Direct preparation of 5-unsubstituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones from a β-Keto carboxylic acid. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 6777–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Lam, Y. A rapid and convenient synthesis of 5-unsubstituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-ones and thiones. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahekar, S.S.; Shinde, D.B. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activity of some [4,6-(4-substituted aryl)-2-thioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-pyrimidin-5-yl]-acetic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 1733–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokale, S.N.; Shinde, S.S.; Elgire, R.D.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Shinde, D.B. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activity of some 3-(4,6-disubtituted-2-thioxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidin-5-yl) propanoic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4424–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Chen, X.-H.; Song, J.; Luo, S.-W.; Fan, W.; Gong, L.-Z. Highly enantioselective organocatalytic Biginelli and Biginelli-like condensations: Reversal of the stereochemistry by tuning the 3,3′-disubstituents of phosphoric acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15301–15310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holla, B.S.; Rao, B.S.; Sarojini, B.; Akberali, P. One pot synthesis of thiazolodihydropyrimidinones and evaluation of their anticancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 39, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.; Wang, X.; Wanga, J.-X.; Du, Z. New three-component cyclocondensation reaction: Microwaveassisted one-pot synthesis of 5-unsubstituted-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 1981–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, J.; Gandomi-Ravandi, S. MnO2–MWCNT nanocomposites as efficient catalyst in the synthesis of Biginelli-type compounds under microwave radiation. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2013, 373, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.C.; Joshi, S.B.; Jadeja, K.A. A one-pot multicomponent Biginelli reaction for the preparation of novel pyrimidinthione derivatives as antimicrobial agents. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020, 57, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, M.; Cadamuro, S.; Dughera, S. A Brønsted acid catalysed enantioselective Biginelli reaction. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Y.; Guo, J.-X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R.; Borovkov, V. Stereoselective Biginelli-like reaction catalysed by a chiral phosphoric acid bearing two hydroxy groups. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 1875–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.-L.; Huang, S.-L.; Pan, Y.-J. Highly Chemoselective multicomponent Biginelli-type condensations of cycloalkanones, urea or thiourea and aldehydes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 2354–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Majee, A.; Hajra, A. Microwave-assisted Brønsted acidic ionic liquid-promoted one-pot synthesis of heterobicyclic dihydropyrimidinones by a three-component coupling of cyclopentanone, aldehydes, and urea. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2010, 47, 1230–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-L.; Wang, P.-C.; Lu, M. Bronsted acidic ionic liquid [C3SO3HDoim]HSO4 catalyzed one-pot three-component Biginelli-type reaction: An efficient and solvent-free synthesis of pyrimidinone derivatives and its mechanistic study. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, P.; Dutta, A.K.; Borah, R. Studies on structural changes and catalytic activity of Y-zeolite composites of 1,3-disulfoimidazolium trifluoroacetate ionic liquid (IL) for three-component synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozadeh, A.; Rahmani, S.; Nemati, F. Poly(ethylene)glycol/AlCl3 as a new and efficient system for multicomponent Biginelli-type synthesis of pyrimidinone derivatives. Heterocycl. Commun. 2013, 19, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Bansal, M.; Kaur, B.; Mishra, T.; Bhatia, A. Synthesis of 4-aryl-4,5-dihydro-1H-indeno[1,2-d]pyrimidines by Biginelli condensation and their antibacterial activities. J. Chem. Sci. 2011, 123, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velpula, R.; Banothu, J.; Gali, R.; Deshineni, R.; Bavantula, R. 1-Sulfopyridinium chloride: Green and expeditious ionic liquid for the one-pot synthesis of fused 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones and thiones under solvent-free conditions. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2015, 26, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Li, X.; Mo, F.; Lin, X. Efficient synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones via a three-component Biginelli-type reaction of urea, alkylaldehyde and arylaldehyde. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2846–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Al-Dhfyan, A.; Al-Omar, M.A. Targeting cancer stem cells with novel 4-(4-substituted phenyl)-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxy/3,4-dimethoxy)-benzoyl-3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H)-one/thiones. Molecules. 2016, 21, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carreiro, E.P.; Sena, A.M.; Puerta, A.; Padrón, J.M.; Burke, A.J. Synthesis of novel 1,2,3-triazole-dihydropyrimidinone hybrids using multicomponent 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (click)–Biginelli reactions: Anticancer activity. Synlett 2020, 31, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.M.; Moustafa, A.H.; Ahmed, N.; El-Sayed, H.A.; Mohamed, A.S.A. Nano-K2CO3-catalyzed Biginelli-type reaction: Regioselective synthesis, DFT study, and antimicrobial activity of 4-aryl-6-methyl-5-phenyl-3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H)-thiones. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 58, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.D.S.; Awasthi, C.; Rai, V.K.; Rai, A. Biorenewable and mercaptoacetylating building blocks in the Biginelli reaction: Synthesis of thiosugar-annulated dihydropyrimidines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 4899–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.D.S.; Rai, A.; Rai, V.K.; Awasthi, C. Biorenewable resources in the Biginelli reaction: Cerium(III)-catalyzed synthesis of novel iminosugar-annulated perhydropyrimidines. Synlett 2007, 12, 1905–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.D.S.; Rai, A.; Rai, V.K.; Awasthi, C. Chiral ionic liquid-catalyzed Biginelli reaction: Stereoselective synthesis of polyfunctionalized perhydropyrimidines. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 1420–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizar, P.; Myrboh, B. Three-component synthesis of 5:6 and 6:6 fused pyrimidines using KF–alumina as a catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5283–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savant, M.M.; Pansuriya, A.M.; Bhuva, C.V.; Kapuriya, N.P.; Naliapara, Y.T. Etidronic acid: A new and efficient catalyst for the synthesis of novel 5-nitro-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones. Catal. Lett. 2009, 132, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodasara, H.B.; Trivedi, A.R.; Kataria, V.P.; Patel, B.G.; Shah, V.H. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of novel substituted pyrimidine scaffold. Med. Chem. Res. 2013, 22, 6121–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.-P.; Lin, Y.; Hu, K.; Liu, Y. Secondary amine-initiated three-component synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones and thiones involving alkynes, aldehydes and thiourea/urea. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.R.; Choudhary, A.S.; Patil, V.S.; Sekar, N. Synthesis, optical properties, dyeing study of dihydropyrimidones (DHPMs) skeleton: Green and regioselectivity of novel Biginelli scaffold from lawsone. Fibers Polym. 2015, 16, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.R.; Dholariya, B.H.; Vakhariya, C.P.; Dodiya, D.K.; Ram, H.K.; Kataria, V.B.; Siddiqui, A.B.; Shah, V.H. Synthesis and anti-tubercular evaluation of some novel pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 1887–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaraj, V.; Selvi, S.T.; Abirami, M. Modified Biginelli reaction: Synthesis of pyrimidoquinoline derivatives. Asian J. Chem. 2019, 31, 1243–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, C.K.; Nipate, A.S.; Chate, A.V.; Songire, V.D.; Patil, A.P.; Gill, C.H. Efficient rapid access to Biginelli for the multicomponent synthesis of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrimidines in room-temperature diisopropyl ethyl ammonium acetate. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 22313–22324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Wu, J.; Lan, H.; Gao, L.; Qian, H.; Fan, K.; Yin, Z. Palladium and Brønsted acid co-catalyzed Biginelli-like multicomponent reactions via in situ-generated cyclic enol ether: Access to spirofuran-hydropyrimidinones. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovics-Tóth, N.; Tajti, A.; Hümpfner, E.; Bálint, E. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one-phosphonates by the microwave-assisted Biginelli reaction. Catalysts 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essid, I.; Lahbib, K.; Kaminsky, W.; Nasr, C.B.; Touil, S. 5-Phosphonato-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones: Zinc triflate catalyzed one-pot multi-component synthesis, X-ray crystal structure and anti-inflammatory activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1142, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebil, E.; Touil, S. Behaviour of β-keto-δ-carbethoxyphosphonates and phosphine oxides in the Biginelli multicomponent reaction: Regioselective synthesis of 5-carbethoxy-6-phosphonomethyl-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-ones. Heterocycles 2012, 85, 2765–2774. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, D.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, C. A convenient synthesis of 5-(O,O-dialkylphosphoryl)-4-aryl-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones. Heteroatom Chem. 2003, 14, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essid, I.; Touil, S. β-Ketophosphonates as substrates in the Biginelli multicomponent reaction: An efficient and straightforward synthesis of phosphorylated dihydropyrimidinones. Arkivoc 2013, 2013, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidway, M.; Mohan, R.; Saxena, S. Solid_supported Hantzsch—Biginelli reaction for syntheses of pyrimidine derivatives. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2003, 11, 2457–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, K.-H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, X.; Chui, W.K.; Lam, Y. Traceless solid-phase synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocycles and their biological evaluations as inhibitors of neuronal sodium channels. J. Comb. Chem. 2004, 6, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebanov, V.A.; Saraev, V.E.; Desenko, S.M.; Chernenko, V.N.; Knyazeva, I.V.; Groth, U.; Glasnov, T.N.; Kappe, C.O. Tuning of chemo- and regioselectivities in multicomponent condensations of 5-aminopyrazoles, dimedone, and aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5110–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh, M.B.; Salunkhe, S.M.; Patil, D.R.; Anbhule, P.V. A novel and efficient one-step synthesis of 2-amino-5-cyano-6-hydroxy-4-aryl pyrimidines and their antibacterial activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 2651–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heravi, M.M.; Derikvand, F.; Ranjbar, L. Sulfamic acid–catalyzed, three-component, one-pot synthesis of [1,2,4]triazolo/benzimidazolo quinazolinone derivatives. Synth. Commun. 2010, 40, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabukhin, S.V.; Plaskon, A.S.; Boron, S.Y.; Volochnyuk, D.M.; Tolmachev, A.A. Aminoheterocycles as synthons for combinatorial Biginelli reactions. Mol. Divers. 2011, 15, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roopan, S.M.; Khan, F.N.; Jin, J.S.; Kumar, R.S. An efficient one-pot three-component cyclocondensation in the synthesis of 2-(2-chloroquinolin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-ones: Potential antitumor agents. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2011, 37, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.L.; Simas, A.M.; Falcão, E.P.D.S.; dos Anjos, J.V. Antinociceptive pyrimidine derivatives: Aqueous multicomponent microwave-assisted synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 3462–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, R.; Jain, A.; Madan, Y.; Menghani, E. A “One Pot,” Environmentally friendly, multicomponent synthesis of 2-amino-5-cyano-4-[(2-aryl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-6-hydroxypyrimidines and their antimicrobial activity. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2014, 51, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Aghaei, M.; Ghamari, N. Synthesis of benzimidazolo[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivatives via a one-pot multicomponent reaction promoted by a chitosan-based composite magnetic nanocatalyst. Chem. Lett. 2015, 44, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, P.; Kaur, T.; Singh, N.; Singh, U.P.; Sharma, A. p-Toluenesulfonic acid-mediated three-component reaction “on-water” protocol for the synthesis of novel thiadiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolin-6(7H)-ones. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khansole, G.S.; Prasad, D.; Angulwar, J.A.; Atar, A.B.; Nagaraja, B.M.; Jadhav, A.H.; Bhosale, V.N. Tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate mediated three-component reaction for the synthesis of thiadiazolo [2,3-b]quinazolin-6-(7H)-ones and antioxidant activity. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 9, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, A.A.; Kamble, R.R.; Chougala, L.S.; Kadadevarmath, J.S.; Maidur, S.R.; Patil, P.S.; Kumbar, M.N.; Marganakop, S.B. Photophysical, electrochemical studies of novel pyrazol-4-yl-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-ones and their anticancer activity. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 6882–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, F.; Shirini, F. Introduction of Fe3O4@SiO2–ZrCl2-MNPs for the efficient promotion of some multi-component reactions under solvent-free conditions. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 11778–11791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajaganti, S.; Kumari, S.; Kumar, D.; Allam, B.K.; Srivastava, V.; Singh, S. An Efficient, green, and solvent-free multi-component synthesis of benzimidazolo/benzothiazolo quinazolinone derivatives using Sc(OTf)3 catalyst under controlled microwave irradiation. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018, 55, 2578–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devineni, S.R.; Madduri, T.R.; Chamarthi, N.R.; Liu, C.-Q.; Pavuluri, C.M. An efficient microwave-promoted three-component synthesis of thiazolo[3,2-a]pyrimidines catalyzed by SiO2–ZnBr2 and antimicrobial activity evaluation. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2019, 55, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, S.Ç.; Akkoç, S.; Türkmenoglu, B.; Sarıpınar, E. Synthesis of novel heterocyclic compounds containing pyrimidine nucleus using the Biginelli reaction: Antiproliferative activity and docking studies. J Heterocycl. Chem. 2020, 57, 2615–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethiya, A.; Soni, J.; Manhas, A.; Jha, P.C.; Agarwal, S. Green and highly efficient MCR strategy for the synthesis of pyrimidine analogs in water via C–C and C–N bond formation and docking studies. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2021, 47, 4477–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y.; Kikuchi, H.; Kubo, T.; Arai, R.; Toguchi, Y.; Yuan, B.; Sunaga, K.; Cho, H. Synthesis of 4,4-disubstituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones and -thiones, the corresponding products of Biginelli reaction using ketone, and their antiproliferative effect on HL-60 cells. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 70, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, S.; Dai, P.; Schaus, S.E. Asymmetric Mannich reaction of dicarbonyl compounds with α-amido sulfones catalyzed by cinchona alkaloids and synthesis of chiral dihydropyrimidones. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 9998–10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, S.; Taoka, B.M.; Ting, A.; Schaus, S.E. Asymmetric Mannich reactions of β-keto esters with acyl imines catalyzed by cinchona alkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11256–11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, J.M.; Schaus, S.E. Enantioselective synthesis of SNAP-7941: Chiral dihydropyrimidone inhibitor of MCH1-R. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7651–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fustero, S.; Catalán, S.; Aceña, J.L.; del Pozo, C. A new strategy for the synthesis of fluorinated 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones. J. Fluor. Chem. 2009, 130, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S.M.; Kumar, R.S.; Libertsen, L.A.; Perumal, S.; Yogeeswari, P.; Sriram, D. A green expedient synthesis of pyridopyrimidine-2-thiones and their antitubercular activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 3012–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.S.; Kumar, P.M.; Kumar, K.A.; Sreenivasulu, M.; Jafar, A.A.; Rambabu, D.; Krishna, G.R.; Reddy, C.M.; Kapavarapu, R.; Shivakumar, K.; et al. A new three-component reaction: Green synthesis of novel isoindolo[2,1-a]quinazoline derivatives as potent inhibitors of TNF-α. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 5010–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, G.R.; Reddy, T.R.; Chary, R.G.; Joseph, S.C.; Mukherjee, S.; Pal, M. β-Cyclodextrin mediated MCR in water: Synthesis of dihydroisoindolo[2,1-a]quinazoline-5,11-dione derivatives under microwave irradiation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 6744–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, N.S.; Shaaban, M.I. Synthesis, antimicrobial, antiquorum-sensing, antitumor and cytotoxic activities of new series of fused [1,3,4]thiadiazoles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 63, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sośnicki, J.C.; Struk, L.; Kurzawski, M.; Perużyńska, M.; Maciejewska, G.; Droździk, M. Regioselective synthesis of novel 4,5-diaryl functionalized 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H)-thiones via a non-Biginelli-type approach and evaluation of their in vitro anticancer activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 3427–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, K.; Arora, D.; Falkowski, D.; Liu, Q.; Moreland, R.S. An efficacious protocol for 4-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones: Synthesis and calcium channel binding studies. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2009, 3258–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sośnicki, J.G. Addition of organolithium and Grignard reagents to pyrimidine-2(1H)-thione: Easy access to 4-substituted 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H)-thiones. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2009, 184, 1946–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Arora, D.; Singh, S. A highly regio-and chemoselective addition of carbon nucleophiles to pyrimidinones. A new route to C4 elaborated Biginelli compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, C.; Katoh, A.; Yokota, Y.; Omote, Y. Controlled reduction of pyrimidin(e)-2(1H)-ones and -thiones with metal hydride complexes. Regioselective preparation of dihydro- and tetrahydro-pyrimidin-2(1H)-ones and the corresponding thiones. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1981, 1622–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, C.; Katoh, A.; Yokota, Y.; Omote, Y. Reaction of pyrimidin-2(1H)-ones and -thiones with organometallic compounds. Regioselective preparation of dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones and –thiones. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1981, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-N.; Wang, S.; Nie, J.; Meng, W.; Yao, Q.; Ma, J.A. Hydrogen-bond-directed enantioselective decarboxylative Mannich reaction of β-ketoacids with ketimines: Application to the synthesis of anti-HIV drug DPC 083. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 3961–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.N.; Li, S.; Nie, J.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.A. Highly enantioselective decarboxylative Mannich reaction of malonic acid half oxyesters with cyclic trifluoromethyl ketimines: Synthesis of β-amino esters and anti-HIV drug DPC 083. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 15856–15860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamthulla, S.; Jana, A.; Choudhury, L.H. Synthesis of novel 5,6-disubstituted pyrrolo [2,3-d]pyrimidine-2,4-diones via one-pot three-component reactions. ACS Comb. Sci. 2017, 19, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangolani, S.K.; Panahi, F.; Tavaf, Z.; Nourisefat, M.; Yousefi, R.; Khalafi-Nezhad, A. Synthesis and antioxidant activity evaluation of some novel aminocarbonitrile derivatives incorporating carbohydrate moieties. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10341–10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.-J.; Shi, L.; Feng, G.-S.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.-G. Enantioselective synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones through organocatalytic transfer hydrogenation of 2-hydroxypyrimidines. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 4435–4442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.-R.; Meng, F.-J.; Jiang, W.-F.; Shi, L. ZrCl4-catalyzed nucleophilic dearomatization of 2-hydroxy-pyrimidines: A concise synthesis of novel 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones containing a phosphonic ester group. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 73, 153149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, S.; Baskaran, S.; König, B. Synthesis of 5-unsubstituted dihydropyrimidinone-4-carboxylates from deep eutectic mixtures. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondhi, S.M.; Jain, S.; Dinodia, M.; Shukla, R.; Raghubir, R. One pot synthesis of pyrimidine and bis-pyrimidine derivatives and their evaluation for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 3334–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C.O. Creating chemical diversity space by scaffold decoration of dihydropyrimidines. Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 77, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanetskyy, B.; Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C.O. Combining Biginelli multicomponent and click chemistry: Generation of 6-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-dihydropyrimidone libraries. J. Comb. Chem. 2004, 6, 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Singh, S.; Mahajan, A. Metalation of Biginelli compounds. A general unprecedented route to C-6 functionalized 4-aryl-3,4-dihydropyrimidinones. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 6114–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Singh, S. A mild and practical method for the regioselective synthesis of N-acylated 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2-ones. New acyl transfer reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 8143–8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.A.; Qin, J.; Robinson, J.E.; Bazin, B. Enantioselective total synthesis of the polycyclic guanidine-containing marine alkaloid (−)-batzelladine D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7417–7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobinikhaledi, A.; Foroughifar, N.; Javidan, A.; Amini, E. Synthesis of some novel fused oxo- and thiopyrimidines via an intramolecular Friedel-Crafts reaction. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 44, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, M.; Holla, B.S.; Kumari, N.S. Convenient one pot synthesis of some novel derivatives of thiazolo[2,3-b]dihydropyrimidinone possessing 4-methylthiophenyl moiety and evaluation of their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 42, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Singh, S. Unprecedented single-pot protocol for the synthesis of N1, C6-linked bicyclic 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones via lithiation of Biginelli compounds. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 11718–11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K. N1,N3-Diacyl-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones: Neutral acyl group transfer reagents. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 10395–10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Choi, B.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, K.K.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, H. Oxidation of Biginelli reaction products: Synthesis of 2-unsubstituted 1,4-dihydropyrimidines, pyrimidines, and 2-hydroxypyrimidines. Synlett 2009, 2009, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Chen, Y.G.; Buono, F.G. Oxidative dehydrogenation of dihydropyrimidinones and dihydropyrimidines. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4673–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karade, N.N.; Gampawar, S.V.; Kondre, J.M.; Tiwari, G.B. A novel combination of (diacetoxyiodo)benzene and tert-butylhydroperoxide for the facile oxidative dehydrogenation of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 6698–6700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Saidi, K.; Khabazzadeh, H. An efficient synthesis of substituted 2-iminothiazolidin-4-one and thiadiazoloquinazolinone derivatives. Mol. Div. 2009, 13, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Arora, D.; Poremsky, E.; Lowery, J.; Moreland, R.S. N1-Alkylated 3,4-dihydropyrimidine-2(1H)-ones: Convenient one-pot selective synthesis and evaluation of their calcium channel blocking activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 1997–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, A.R.; Bhuva, V.R.; Dholariya, B.H.; Dodiya, D.K.; Kataria, V.B.; Shah, V.H. Novel dihydropyrimidines as a potential new class of antitubercular agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6100–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Arora, D.; Balzarini, J. Regioselective addition reactions at C-2 of 3,4-dihydropyrimidinones. Synthesis and evaluation of multifunctionalized tetrahydropyrimidines. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 8175–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Singh, K.; Wan, B.; Franzblau, S.; Chibale, K.; Balzarini, J. Facile transformation of Biginelli pyrimidin-2(1H)-ones to pyrimidines. In vitro evaluation as inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and modulators of cytostatic activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2290–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K. An efficacious protocol for the oxidation of 3, 4-dihydropyrimidin-2 (1H)-ones using pyridinium chlorochromate as catalyst. Aust. J. Chem. 2008, 61, 910–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Kaur, H.; Chibale, K.; Balzarini, J.; Little, S.; Bharatam, P.V. 2-Aminopyrimidine based 4-aminoquinoline anti-plasmodial agents. Synthesis, biological activity, structure activity relationship and mode of action studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 52, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Singh, K.; Trappanese, D.M.; Moreland, R.S. Highly regioselective synthesis of N-3 organophosphorous derivatives of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones and their calcium channel binding studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 54, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, H.M.; Kamal, M.M. Efficient one-pot preparation of novel fused chromeno[2,3-d]pyrimidine and pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, P.S.; Bhuyan, P. A novel one-pot three-component reaction for the synthesis of 5-arylamino-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines under microwave irradiation. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 9942–9945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, T.; Zhang, G. Iron-catalyzed vinylogous aldol condensation of Biginelli products and its application toward pyrido[4,3-d]pyrimidinones. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2281–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, J.; Saini, M.; Kumar, S.; Verma, P.K. Design, synthesis and biological potentials of novel tetrahydroimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine derivatives. Chem. Cent. J. 2017, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Zou, C.; Gao, Z.; Fan, C.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, G.; Yu, H. Enantioselective Biginelli reaction of aliphatic aldehydes catalyzed by a chiral phosphoric acid: A key step in the synthesis of the bicyclic guanidine core of crambescin A and batzelladine A. Synthesis 2018, 50, 2394–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, M.A.; Day, K.A.; Durón, S.G.; Gin, D.Y. Total synthesis of (+)-batzelladine A and (−)-batzelladine D via [4 + 2]-annulation of vinyl carbodiimides with N-alkyl imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13255–13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gondru, R.; Peddi, S.R.; Manga, V.; Khanapur, M.; Gali, R.; Sirassu, N.; Bavantula, R. One-pot synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies of fused thiazolo[2,3-b]pyrimidinone-pyrazolylcoumarin hybrids. Mol. Divers. 2018, 22, 943–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveka, S.; Nagaraja, G.K.; Shama, P.; Basavarajaswamy, G.; Rao, K.P.; Sreenivasa, M.Y. One pot synthesis of thiazolo[2,3-b]dihydropyrimidinone possessing pyrazole moiety and evaluation of their anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities. Med. Chem. Res. 2018, 27, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveka, S.; Shama, P.; Naveen, S.; Lokanath, N.K.; Nagaraja, G.K. Design, synthesis, anticonvulsant and analgesic studies of new pyrazole analogues: A Knoevenagel reaction approach. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 94786–94795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brandolese, A.; Ragno, D.; Leonardi, C.; Di Carmine, G.; Bortolini, O.; De Risi, C.; Massi, A. Enantioselective N-acylation of Biginelli dihydropyrimidines by oxidative NHC catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 2439–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Sancho, F.; Escolano, M.; Gaviña, D.; Csáky, A.G.; Sánchez-Roselló, M.; Díaz-Oltra, S.; del Pozo, C. Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidin(thio)one Containing Scaffold: Biginelli-like Reactions. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15080948

Sánchez-Sancho F, Escolano M, Gaviña D, Csáky AG, Sánchez-Roselló M, Díaz-Oltra S, del Pozo C. Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidin(thio)one Containing Scaffold: Biginelli-like Reactions. Pharmaceuticals. 2022; 15(8):948. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15080948

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Sancho, Francisco, Marcos Escolano, Daniel Gaviña, Aurelio G. Csáky, María Sánchez-Roselló, Santiago Díaz-Oltra, and Carlos del Pozo. 2022. "Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidin(thio)one Containing Scaffold: Biginelli-like Reactions" Pharmaceuticals 15, no. 8: 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15080948

APA StyleSánchez-Sancho, F., Escolano, M., Gaviña, D., Csáky, A. G., Sánchez-Roselló, M., Díaz-Oltra, S., & del Pozo, C. (2022). Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydropyrimidin(thio)one Containing Scaffold: Biginelli-like Reactions. Pharmaceuticals, 15(8), 948. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15080948