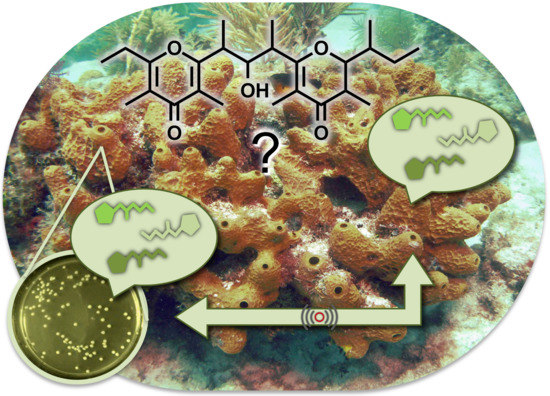

Isolation of Smenopyrone, a Bis-γ-Pyrone Polypropionate from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia aurea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedure

4.2. Collections, Extraction, and Isolation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilk, W.; Waldmann, H.; Kaiser, M. γ-Pyrone natural products—A privileged compound class provided by nature. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2304–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik, J.R. Marine Invertebrate Chemical Defenses. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies-Coleman, M.T.; Garson, M.J. Marine polypropionates. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1998, 15, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, M.; Ciavatta, M.L.; Wang, J.R.; Cirillo, I.; Mathieu, V.; Kiss, R.; Mollo, E.; Guo, Y.W.; Gavagnin, M. Extending the Record of Bis-γ-pyrone Polypropionates from Marine Pulmonate Mollusks. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 2065–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.F.; Li, X.L.; Yao, L.G.; Li, J.; Gavagnin, M.; Guo, Y.W. Marine bis-γ-pyrone polypropionates of onchidione family and their effects on the XBP1 gene expression. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 1093–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suenaga, K.; Kigoshi, H.; Yamada, K. Auripyrones A and B, cytotoxic polypropionates from the sea hare Dolabella auricularia: Isolation and structures. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 5151–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Petit, G.R.; Hamel, E. Dolastatin 10, a powerful cytostatic peptide derived from a marine animal: Inhibition of tubulin polymerization mediated through the vinca alkaloid binding domain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990, 39, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, V.; Fattorusso, E.; Imperatore, C.; Mangoni, A. Ectyoceramide, the First Natural Hexofuranosylceramide from the Marine Sponge Ectyoplasia ferox. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 8, 1433–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, V.; D’Esposito, M.; Fattorusso, E.; Mangoni, A.; Basilico, N.; Parapini, S.; Taramelli, D. Damicoside from Axinella damicornis: The influence of a glycosylated galactose 4-OH group on the immunostimulatory activity of α-galactoglycosphingolipids. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 7411–7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, V.; Fattorusso, E.; Imperatore, C.; Mangoni, A. Glycolipids from sponges. Part 17. Clathrosides and Isoclathrosides, Unique Glycolipids from the Caribbean Sponge Agelas clathrodes. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamoral-Theys, D.; Fattorusso, E.; Mangoni, A.; Perinu, C.; Kiss, R.; Costantino, V. Evaluation of the antiproliferative activity of diterpene isonitriles from the sponge Pseudoaxinella flava in apoptosis-sensitive and apoptosis-resistant cancer cell lines. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 2299–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; Della Sala, G.; Teta, R.; Caso, A.; Bourguet-Kondracki, M.L.; Pawlik, J.R.; Mangoni, A.; Costantino, V. Chlorinated Thiazole-Containing Polyketide-Peptides from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia conulosa: Structure Elucidation on Microgram Scale. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 16, 2871–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, A.; Mangoni, A.; Piccialli, G.; Costantino, V.; Piccialli, V. Studies toward the Synthesis of Smenamide A, an Antiproliferative Metabolite from Smenospongia aurea: Total Synthesis of ent-Smenamide A and 16-epi-Smenamide A. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caso, A.; Laurenzana, I.; Lamorte, D.; Trino, S.; Esposito, G.; Piccialli, V.; Costantino, V. Smenamide A Analogues. Synthesis and Biological Activity on Multiple Myeloma Cells. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik, J.R. Thechemical ecology of sponges on Caribbeanreefs: Natural products shape natural systems. Bioscience 2011, 61, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, V.; Fattorusso, E.; Mangoni, A.; Perinu, C.; Teta, R.; Panza, E.; Ianaro, A. Tedarenes A and B: Structural and stereochemical analysis of two new strained cyclic diarylheptanoids from the marine sponge Tedania ignis. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6377–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangoni, A. Strategies for Structural Assignment of Marine Natural Products Through Advanced NMR-based Techniques. In Handbook of Marine Natural Products; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 518–546. [Google Scholar]

- Manker, D.C.; Faulkner, D.J.; Xe, C.F.; Clardy, J. Metabolites of Siphonaria maura from Costa Rica. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 814–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, J.S.; Perkins, M.V. Total Synthesis and Structural Elucidation of (−)-Maurenone. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwink, L.; Knochel, P. Enantioselective Preparation of C2-Symmetrical Ferrocenyl Ligands for Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 1998, 4, 950–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, N.; Iwatsuki, M.; Suenaga, K.; Uemura, D. Pinnamine, an alkaloidal marine toxin, isolated from Pinna muricata. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 6425–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutignano, A.; Villani, G.; Fontana, A. One metabolite, two pathways: Convergence of polypropionate biosynthesis in fungi and marine molluscs. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Torres, J.P.; Ammon, M.A.; Marett, L.; Teichert, R.W.; Reilly, C.A.; Kwan, J.C.; Hughen, R.W.; Flores, M.; Tianero, M.D.; et al. A bacterial source for mollusk pyrone polyketides. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hentschel, U.; Usher, K.M.; Taylor, M.W. Marine sponges as microbial fermenters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006, 55, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Laroche, M.; Imperatore, C.; Grozdanov, L.; Costantino, V.; Mangoni, A.; Hentschel, U.; Fattorusso, E. Cellular localisation of secondary metabolites isolated from the Caribbean sponge Plakortis simplex. Mar. Biol. 2007, 151, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, A.L.; Peraud, O.; Kasanah, N.; Sims, J.W.; Kothalawala, N.; Anderson, M.A.; Abbas, S.H.; Rao, K.V.; Jupally, V.R.; Kelly, M.; et al. An analysis of the sponge Acanthostrongylophora igens’ microbiome yields an actinomycete that produces the natural product manzamine A. Front. Mar. Sci. 2014, 1, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; Bourguet-Kondracki, M.L.; Mai, L.H.; Longeon, A.; Teta, R.; Meijer, L.; Van Soest, R.; Mangoni, A.; Costantino, V. Chloromethylhalicyclamine B, a Marine-Derived Protein Kinase CK1δ/ε Inhibitor. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2953–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.F.; Venturi, V. A novel widespread interkingdom signaling circuit. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardères, J.; Taupin, L.; Saidin, J.B.; Dufour, A.; Le Pennec, G. N-acyl homoserine lactone production by bacteria within the sponge Suberites domuncula (Olivi, 1972) (Porifera, Demospongiae). Mar. Biol. 2012, 159, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardères, J.; Henry, J.; Bernay, B.; Ritter, A.; Zatylny-Gaudin, C.; Wiens, M.; Müller, W.E.; Le Pennec, G. Cellular Effects of Bacterial N-3-Oxo-Dodecanoyl-L-Homoserine Lactone on the Sponge Suberites domuncula (Olivi, 1792): Insights into an Intimate Inter-Kingdom Dialogue. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Costantino, V.; Della Sala, G.; Saurav, K.; Teta, R.; Bar-Shalom, R.; Mangoni, A.; Steindler, L. Plakofuranolactone as a Quorum Quenching Agent from the Indonesian Sponge Plakortis cf. lita. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachmann, A.O.; Brameyer, S.; Kresovic, D.; Hitkova, I.; Kopp, Y.; Manske, C.; Schubert, K.; Bode, H.B.; Heermann, R. Pyrones as bacterial signaling molecules. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teta, R.; Della Sala, G.; Glukhov, E.; Gerwick, L.; Gerwick, W.H.; Mangoni, A.; Costantino, V. Combined LC−MS/MS and Molecular Networking Approach Reveals New Cyanotoxins from the 2014 Cyanobacterial Bloom in Green Lake, Seattle. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 14301–14310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, G.; Teta, R.; Miceli, R.; Ceccarelli, L.S.; Della Sala, G.; Camerlingo, R.; Irollo, E.; Mangoni, A.; Pirozzi, G.; Costantino, V. Isolation and Assessment of the in Vitro Anti-Tumor Activity of Smenothiazole A and B, Chlorinated Thiazole-Containing Peptide/Polyketides from the Caribbean Sponge, Smenospongia aurea. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teta, R.; Irollo, E.; Della Sala, G.; Pirozzi, G.; Mangoni, A.; Costantino, V. Smenamides A and B, Chlorinated Peptide/Polyketide Hybrids Containing a Dolapyrrolidinone Unit from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia aurea. Evaluation of Their Role as Leads in Antitumor Drug Research. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 4451–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Position | δC, Type | δH, Mult (J in Hz) | HMBC a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11.7 (CH3) | 1.25 (t, 7.5) | 2, 3 | |

| 2 | 25.7 (CH2) | a,b | 2.71 (m) | 1, 3 |

| 3 | 167.5 (C) | - | ||

| 4 | 119.0 (C) | - | ||

| 5 | 182.0 (C) | - | ||

| 6 | 120.3 (C) | - | ||

| 7 | 167.7 (C) | - | ||

| 8 | 41.7 (CH) | 3.15 (quintet, 7.1) | 9, 21 | |

| 9 | 75.6 (CH) | 4.02 (t, 7.1) | 7, 8, 21, 22 | |

| 10 | 41.5 (CH) | 2.93 (quintet, 7.0) | 9, 11, 22 | |

| 11 | 175.6 (C) | - | ||

| 12 | 109.2 (C) | - | ||

| 13 | 197.9 (C) | - | ||

| 14 | 41.5 (CH) | 2.53 (dq, 12.8, 6.9) | 13, 15, 24 | |

| 15 | 88.0 (CH) | 3.84 (dd, 12.8, 3.0) | ||

| 16 | 36.6 (CH) | 1.78 (m) | ||

| 17 | 23.0 (CH2) | a | 1.64 (m) | |

| b | 1.29 (m) | |||

| 18 | 12.1 (CH3) | 0.98 (t, 7.5) | 16, 17 | |

| 19 | 9.6 (CH3) | 1.93 (s) | 3, 4, 5 | |

| 20 | 10.1 (CH3) | 1.91 (s) | 5, 6, 7 | |

| 21 | 15.5 (CH3) | 1.28 (d, 7.1) | 7, 8, 9 | |

| 22 | 14.1 (CH3) | 1.26 (d, 6.9) | 9, 10, 11 | |

| 23 | 9.4 (CH3) | 1.63 (s) | 11, 12, 13 | |

| 24 | 10.7 (CH3) | 1.06 (d, 6.9) | 13, 14, 15 | |

| 25 | 16.6 (CH3) | 1.11 (d, 6.9) | 15, 16, 17 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esposito, G.; Teta, R.; Della Sala, G.; Pawlik, J.R.; Mangoni, A.; Costantino, V. Isolation of Smenopyrone, a Bis-γ-Pyrone Polypropionate from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia aurea. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16080285

Esposito G, Teta R, Della Sala G, Pawlik JR, Mangoni A, Costantino V. Isolation of Smenopyrone, a Bis-γ-Pyrone Polypropionate from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia aurea. Marine Drugs. 2018; 16(8):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16080285

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsposito, Germana, Roberta Teta, Gerardo Della Sala, Joseph R. Pawlik, Alfonso Mangoni, and Valeria Costantino. 2018. "Isolation of Smenopyrone, a Bis-γ-Pyrone Polypropionate from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia aurea" Marine Drugs 16, no. 8: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16080285

APA StyleEsposito, G., Teta, R., Della Sala, G., Pawlik, J. R., Mangoni, A., & Costantino, V. (2018). Isolation of Smenopyrone, a Bis-γ-Pyrone Polypropionate from the Caribbean Sponge Smenospongia aurea. Marine Drugs, 16(8), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/md16080285