Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

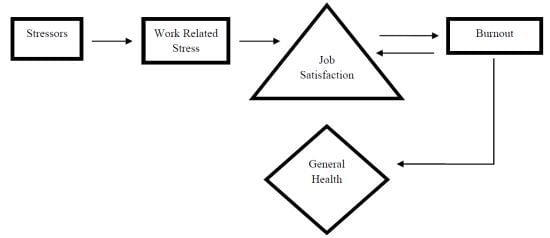

- Do existing studies identify the causal nature and direction of relationships between work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses?

- Do existing studies focus mostly on two and three way relationships between work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses?

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategies

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Work Related Stress and Burnout

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution at conferences and meetings) [25] | 132 nurses (132 women & 22 men) working in different wards and clinics [25] | Working place/nursing role was associated with higher burnout among practicing nurses compared to those who had a managerial function (as head nurse, deputy, or mentor) (t = 3.2, p < 0.01) owing to limited support with complicated treatments, less power, lower status and lack of variation in roles [25] |

| Quantitative (extensive questionnaire survey) [26] | 1,190 registered nurses working in 43 public hospitals [26] | Social context related stressors (lack of professional recognition, professional uncertainty, interpersonal and family conflicts, tension in professional work relationships as well as tensions in nurse-patient relationships) were all significantly associated with emotional exhaustion (β = 0.44, p ≤ 0.01), depersonalization (β = 0.26, p ≤ 0.01) and personal accomplishment (β = −0.33, p ≤ 0.01). Job content related stressors including patient care responsibilities, job demands and role conflict) also had significant relationships with emotional exhaustion (β = 0.22, p ≤ 0.01), and personal accomplishment (β = 0.23, p ≤ 0.01) but not with depersonalization (β = −0.04, p ≥ 0.01) [26] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution and collection in 2 weeks) [27] | 336 nurses (27 male and 309 female) at three hospitals specializing in acute treatment [27] | Emotional exhaustion positively correlated with qualitative workload (β = 0.22, p < 0.01), quantitative workload (β = 0.42, p < 0.01) and conflict with patients (β = 0.19, p < 0.01). Depersonalization was positively related to conflict with other nursing staff (β = 0.28, p < 0.01), qualitative workload (β = 0.15, p < 0.05), quantitative workload (β = 0.19, p < 0.01) and conflict with patients (β = 0.24, p < 0.01) while being negatively related to nursing role conflict (β = −0.17, p < 0.01). Personal accomplishment was negatively correlated with qualitative workload (β = −0.21, p < 0.01) and quantitative workload (β = −0.19, p < 0.01) while being positively correlated with nursing role conflict (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) [27] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution with reminders to non responders [28] | 492 nurses from long stay wards at 5 psychiatric hospitals [28] | Work environment stressors such as job complexity, feedback/clarity, the level of performance of the patient group and social leadership style explained 16% (adjusted R²) of the variance in emotional exhaustion. Job complexity, feedback/clarity and social leadership style explained 12% of the variance in depersonalization. 11% of the variance in personal accomplishment was explained by feedback/clarity and job complexity [28] |

| Quantitative and Qualitative (All nurses received questionnaires with 5 being selected to participate in a semi-structured interview) [29] | 30 community clinical HIV/AIDS nurse specialists [29] | Significant correlations were found between emotional exhaustion and grief/loss (τ = 0.58, p < 0.05), emotional exhaustion and loss tolerance/peer relationship (τ = 0.41, p < 0.05), personal accomplishment and social recognition/reward (τ = 0.40, p < 0.05). A weak but significant relationship was found between emotional exhaustion and stigma/discrimination (τ = 0.29, p < 0.05). Qualitative findings indicated that death of a patient and stigma/grief were related to burnout [29] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution and completion at 2 time points) [30] | 98 nurses attending a post-work course towards a licentiate degree [30] | Amount of variance explained increased (ΔR² = 0.14, p < 0.001) when work related stressors were entered into the burnout model. Work overload was the only stressor that significantly predicted emotional exhaustion (β = 0.35, p < 0.01). Experience with pain and death significantly predicted depersonalization (β = −0.38, p < 0.001) and role ambiguity (β = 0.32, p < 0.05) while lack of cohesion (β = 0.24, p < 0.05) significantly predicted the lack of personal accomplishment [30] |

| Quantitative (Questionnaires posted to members of the Association of Nurses in AIDs Care) [31] | 445 nurses providing care to people living with HIV/AIDS [31] | Findings confirmed association between perceived workload (hours worked and amount of work) and burnout (r = 0.24, p < 0.01). Workload accounted for 5.6% of the variance in burnout [31] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire packages were mailed to nurses) [32] | 574 Australian Nursing Federation members [32] | Generally, working overtime was positively related to higher emotional exhaustion (r = 0.21, p < 0.05). Being pressured or expected to work overtime (involuntarily) was related to higher emotional exhaustion (r = 0.41, p < 0.05) and depersonalization (r = 0.22, p < 0.05); while working unpaid overtime was also associated with higher emotional exhaustion (r = 0.13, p < 0.05) [32] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by nominated coordinator at each hospital) [33] | 495 nurses from three provincial hospitals [33] | Role insufficiency was significantly related to exhaustion (r = 0.38, p < 0.05), cynicism (r = 0.39, p < 0.05) and professional efficacy (r = 0.28, p < .05). Role ambiguity was significantly related to exhaustion (r = 0.20, p < 0.05), cynicism (r = 0.28, p < 0.05) and professional efficacy (r = 0.27, p < 0.05). Role boundary was significantly related to exhaustion (r = 0.29, p < 0.05), cynicism (r = 0.34, p < 0.05) and professional efficacy (r = 0.21, p < 0.05). Responsibility, physical environment, and role overload are all significantly related to exhaustion (r = 0.33, p < 0.05, r = 0.31, p < 0.05, r = 0.42, p < 0.05 respectively) and cynicism (r = 0.28, p < 0.05, r = 0.20, p < 0.05, r = 0.30, p < 0.05 respectively) [33] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution via the hospital’s internal mail system) [34] | 101 registered nurses, employed at a major specialist oncology metropolitan hospital [34] | Significant correlations were found between nursing stressors (lack of support, poor communication with doctors) and emotional exhaustion (r = 0.48, p < 0.01) as well as depersonalization (r = 0.34, p < 0.01), but not personal accomplishment [34] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution after receiving consent) [35] | 292 nurses working at a state hospital [35] | Doctor/nurse conflict (OR = 3.1; 95% CI, 1.9–6.3), low doctor/nurse ratio (OR = 6.1; 95% CI, 2.5–13.2), inadequate nursing personnel (OR = 2.6; 95% CI, 1.5–5.1) and too frequent night duties (OR = 3.1; 95% CI, 1.7–5.6) were significant predictors of emotional exhaustion. Doctor/nurse conflict (OR = 3.4; 95% CI, 2.2–7.6), low doctor/nurse ratio (OR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.4– 4.1), and too frequent night duties (OR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.5– 4.8) significantly predicted depersonalization. High nursing hierarchy (OR = 2.7; 95% CI, 1.5–4.8), poor wages (OR = 2.9; 95% CI, 1.6–5.6) and too frequent night duties (OR = 2.3; 95% CI, 2.3–4.5) significantly predicted reduced personal accomplishment [35] |

3.2. Work Related Stress and Job Satisfaction

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative (interviews, observations and field notes) [36] | 8 nurses selected from a local nursing agency [36] | Thematic analysis revealed that nurses were most satisfied with compensation (patient outcomes, compliments, salary, incentives and lessons learned), team spirit (working together and sharing duties), strong support from physicians and advocacy (assisting and supporting new nurses) [36] |

| Quantitative (questionnaires were sent out with each nurses’ paycheck) [37] | 249 nurses employed at a children’s hospital [37] | In general job stress was found to be significantly associated with job satisfaction (r = 0.64, p < 0.05). Pay (r = 0.40, p < 0.05, r = 0.43, p < 0.05), interaction/cohesion (r = 0.44, p < 0.05, r = .41, p < 0.05) and task requirements (r = 0.53, p < 0.05, r = 0.67, p < 0.05) were significantly associated with both job stress and job satisfaction respectively [37] |

| Quantitative (questionnaires were mailed to nurses) [38] | 944 RN’s working in rural and remote hospital settings [38] | Workplace stressors explained 32% of the variance in job satisfaction. Having available, well maintained and up-to-date equipment and supplies was highly related to job satisfaction, accounting for 17% of the total variance. Greater scheduling and shift satisfaction (no overtime) as well as lower psychological job demands (fewer time constraints, less excessive workloads) were strong predictors of job satisfaction (accounting for 12% of the variance) [38] |

| Quantitative (survey packets with instructions were placed in staff mailboxes) [39] | 116 medical-surgical nurses working in acute-care settings [39] | Only one environmental factor, noise, was significantly associated with perceived stress (r = −0.18, p = 0.05). Perceived stress was directly related to job satisfaction (r = 0.55, p = 0.00) [39] |

| Quantitative (survey distribution via the hospital’s internal mail) [40] | 135 nurses employed in a 170 bed hospital [40] | Work content stressors including variety, autonomy, task identity and feedback are all strongly correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.35–0.50, p < 0.001). Work environment stressors including collaboration with medical staff and cohesion among nurses are also strongly correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.37–0.45, p < 0.001). Job satisfaction was mostly predicted by variety, feedback and collaboration with medical staff (r = 0.55, R² = 0.30) [40] |

| Quantitative (E-mails containing a $5 e-mail gift certificate and a web link to the survey instrument were sent. Reminder e-mails were sent to non responders) [41] | 362 registerednurses in a large metropolitan hospital [41] | Job satisfaction was positively and significantly correlated with physical work environment (r = 0.26, p < 0.01). Significant positive predictors of job satisfaction from the baseline model were autonomy (β = 0.09, p < 0.05), supervisor support (β = 0.05, p < 0.05), workgroup cohesion (β = 0.09, p < 0.05), working in a unit other than the intensive care unit (β = 0.67, p < 0.05), working in a step-down unit or general medical surgical unit (β = 0.31, p < 0.05), and number of hours of voluntary overtime worked in a typical work week (β = 0.05, p < 0.05). A negative significant predictor was working a 12-hour shift (β = −0.83, p < 0.05) [41] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution through the nurse manager of each unit) [42] | 431 critical care nurses, all of whom were RN’s working at 16 different hospitals [42] | Professional autonomy had a moderate positive correlation with reported role conflict and role ambiguity (r = 0.33, p < 0.001). A positive moderate correlation between professional autonomy and job satisfaction was found (r = 0.33, p < 0.001) [42] |

| Quantitative (anonymous questionnaire distribution) [43] | 117 Registered Nurses (77 Army RNs – 40 Civilian RNs) [43] | Work related stress was inversely correlated with job satisfaction for both civilian (r = −0.32, p < 0.05) and army (r = −0.23, p < 0.05) nurses. Army nurses were most stressed and least satisfied by their working relations with colleagues (r = −0.40, p < 0.01), while civilian nurses were most stressed and least satisfied with their physical working environments (r = 0.32, p < 0.05) [43] |

| Quantitative (participants were invited by e-mail to attend a one-day event where they completed surveys) [44] | 271 public health nurses [44] | Control-over-practice (x² = 7.22, p = 0.01; OR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02) and workload (x² = 15.04, p < 0.01; OR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.86–0.95) significantly predicted job satisfaction. The strongest association was found between workload and job satisfaction, whereby a one-unit increase on the work overload scale decreased the odds of job satisfaction by nearly 10%. The interaction between autonomy and workload was a significant predictor of job satisfaction (x² = 15.87, p < 0.01) [44] |

| Quantitative (voluntary completion of standardized questionnaires) [45] | 129 qualified nurses [45] | Results showed that workload was the highest perceived stressor in the nurses’ working environment (M = 1.61, SD ± 0.88). Nursing stress was found to be negatively and significantly correlated with job satisfaction (r = −0.22, p < 0.05). Nurse stress predictor variables combined accounted for 17% of the variance in job satisfaction (R² = 0.17, F (3, 123) = 8.9, p < 0.001) [45] |

| Quantitative (distribution of questionnaire packets) [46] | 140 registered nurses from medical-surgical, management and home health nursing specialties [46] | There was a significantly positive correlation between job satisfaction and perceived autonomy (r = 0.538, p < 0.05) [46] |

| Quantitative (surveys were made available in each unit and were also distributed to nurses during unit meetings with incentives) [47] | 205 nurses employed at a at a large women andchildren’s hospital [47] | Nurses’ perceptions of physicians’ nurse centered communication was significantly related to job satisfaction (r = 0.23, p = 0.002). Physicians’ nurse centered communication behaviors examined as predictors of nurses’ reported job satisfaction revealed a significant model (F (5, 160) = 3.86, R² = 0.11, p = 0.003, with humor and clarity being the most significant predictors of job satisfaction). Work environment, meaningfulness of work, and stress also significantly predicted job satisfaction in another model (F (7, 188) = 27.40, R² = 0.51, p = 0.001) [47] |

| Quantitative (anonymous questionnaire distribution and collection) [48] | 532 nurses with job rotation experience [48] | Structural equation modeling revealed a negative relationship between role stress and job satisfaction (γ = 0.52, p < 0.01) [48] |

| Quantitative (survey distribution by nurse managers. Follow up surveys were redistributed after 2 weeks to boost response rate) [49] | 287 registered nurses employed in state prison health care facilities [49] | The nursing stress score was the strongest explanatory variable, accounting for 30.3% of the variance in job satisfaction. An inverse relationship between nursing stress and job satisfaction was confirmed (β = −0.55, p < 0.01) [49] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by graduate students and administrative staff to nurses’ onsite mailboxes) [50] | 464 RNs employed in five acute care hospitals [50] | Work related stress (including personal stressors (r = −0.11, p < 0.05) as well as situational stressors (r = −0.30, p < 0.05)) were negatively correlated with job satisfaction. Regression analysis further confirmed that work related stress (personal stressors (R² = 0.29, p < 0.05) as well as situational stressors (R² = 0.29, p < 0.05)) is a significant predictor of job satisfaction [50] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by nurse administrators) | 285 nurses from six hospitals | The strongest association was found between job related stress and job satisfaction, which were inversely related (rs = −0.331, p < 0.05). It was concluded that nurses who experience higher stress levels are less satisfied with their jobs. |

3.3. Work Related Stress and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (distribution of self administered questionnaires) [52] | 420 registered nurses and student nurses from public hospitals [52] | The frequency of stressful situations and emotionally provoking problems as well as the lack of social support from peers were the only factors significantly associated with psychosomatic health complaints among registered nurses (R² = 0.11, p < 0.01) and student nurses (R² = 0.06, p < 0.05), after controlling for other variables [52] |

| Quantitative and qualitative (distribution of questionnaires and interviews by a neurologist) [53] | 779 nursing staff at a tertiary medical center [53] | Work overload (M = 3.32, SD ± 0.74, p < 0.001) and health status (M = 2, SD ± 1.16, p < 0.001) were the most significant stressors among headache sufferers [53] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution at an event) [54] | 372 community nurses [54] | High job demands (OR = 2.15; 95% CI, 1.07–4.30), low job control (OR = 1.22; 95% CI, 0.64–2.31) and job strain/low social support at work (OR = 3.78; 95% CI, 2.08–6.87) were related to mental distress. In conclusion, mental distress among the nurses is associated with occupational stress elicited by adverse psychosocial job characteristics [54] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire packets distributed by head nurse for each unit) [55] | 480 hospital nurses from five hospitals in three major cities [55] | The most frequently occurring workplace stressor was workload (M = 9.18, SD ± 3.93). Work place stressors including workload (r = −0.21, p < 0.01, r = −0.30, p < 0.01), physician conflict (r = −0.24, p < 0.01, r = −0.25, p < 0.01), death/dying (r = −0.18, p < 0.01, r = −0.17, p < 0.01), nurse conflict (r = −0.27, p < 0.01, r = −0.28, p < 0.01), lack of support (r = −0.11, p < 0.01, r = −0.14, p < 0.01), inadequate preparation (r = −0.17, p < 0.01, r = −0.23, p < 0.01) and treatment uncertainty (r = −0.25, p < 0.01, r = −0.26, p < 0.01) were all significantly correlated with physical and mental health respectively. Work place stress is related to physical and mental health [55] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by principal nursing officers in each unit) [56] | 1,043 nurses of different grades/ranks/departments [56] | Work stress was found to be negatively related to psychological well-being of the nurses, with stronger effects on anxiety and depression (r = −0.44, p < 0.001) [56] |

| Quantitative (online surveys with email reminders to non responders) [57] | 3,132 registered nurses from five multi-state settings [57] | Perceived work stress levels was confirmed as a strong predictor of poor health among nurses (OR = 1.09; 95% CI, 1.05–1.13) [57] |

3.4. Work Related Stress, Burnout and Job Satisfaction

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (nurses were sent surveys at their home mailing address) [58] | 95,499 nurses from 614 hospitals in four states [58] | Nurses providing direct care for patients reported higher burnout (94%) and job dissatisfaction (64%). A third of nurses working in poor environments were dissatisfied with their jobs. Nurses who were satisfied with their jobs were twice as high for those working in better environments. It was concluded that nursing roles and working environments affect burnout and job satisfaction among nurses [58] |

| Quantitative (Surveys were delivered to nurses by nurse managers) [59] | 1,104 bedside nurses in 89 medical, surgical and intensive care units at 21 hospitals [59] | Improving the work environments of nurses (from poor to better) was associated with a 50% decrease in job dissatisfaction and a 33% decrease in burnout. The chances of higher burnout and job dissatisfaction were lower among nurses working in good environments than those working in poor environments, by OR = 0.67 and 0.50, respectively. Nurses working in poor environments were 1.5 and 2 times more likely than those working in good environments to experience burnout and job dissatisfaction [59] |

| Quantitative (the questionnaires were hand delivered to participants and collected within a week) [60] | 60 nurses from 3 hospitals [60] | Non satisfactory relations with physicians (M = 30.2, SD ± 6.6, M = 10.8, SD ± 4.8, M = 25.9, SD ± 10) and high difficulty in meeting patient care needs (M = 32.8, SD ± 6, M = 12.2, SD ± 5.1, M = 25.3, SD ± 11.7) as well as low work satisfaction (M = 27.5, SD ± 8, M = 9.3, SD ± 4.5, M = 28.1, SD ± 10.6) were all significantly associated with higher emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization as well as low personal accomplishment respectively. High nursing workload (M = 17.2, SD ± 7.1, M = 35.3, SD ± 8.2) was associated with higher emotional exhaustion and depersonalization respectively [60] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution and return in sealed envelopes) [61] | 1,365 nurses from 65 intensive care units at 22 hospitals [61] | Perceived adequate staffing was related to decreases in the odds of dissatisfaction (OR = 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23–0.40) and burnout (OR = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.34–0.73) [61] |

| Quantitative (questionnaires were distributed through the hospitals internal mail systems [62] | 5,006 English nurses and 3773 Scottish nurses [62] | Significant relationships were confirmed between nurse staffing (nurse to patient ratio) and burnout (odds ratios for burnout increased from 0.57 to 0.67 to 0.80 to 1.00 as the number of patients a nurse was responsible for increased from 0–4 to 5–8 to 9–12 to 13 or greater). The relationship between nurse staffing and job dissatisfaction was also significant (OR = 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71–0.93) [62] |

| Quantitative (nurses were invited to voluntarily complete questionnaires distributed by an assigned person) [63] | 401 staff nurses across 31 units in two hospitals [63] | The improved model confirmed the mediating role of burnout (depersonalization and personal accomplishment) in the relationship between nurse practice environment related stress (nurse-physician relationship, nurse management, hospital management and organizational support,) and job outcomes (including job satisfaction) (x² = 548.1; d.f. = 313; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.906; IFI = 0.903; RMSEA = 043) [63] |

| Quantitative (nurses were invited to voluntarily complete questionnaires distributed by an assigned person) [64] | 155 medical, surgical and surgical intensive care unit nurses across 13 units in three hospitals [64] | Nurse–physician relations had a significant positive association with nurse job satisfaction (OR = 7.7; 95% CI, 2.6–22.7) and personal accomplishment (OR = 3.5, S.E. ± 0.8), nurse management at the unit level had a significant positive association with the nurse job satisfaction (OR = 3.6; 95% CI, 1.3–10) and personal accomplishment (OR = 2.7, S.E. ± 0.1.1), hospital management and organizational support had a significant positive association with personal accomplishment (OR = 2.1, S.E. ± 1). Nurse–physician relations (OR = −3.9, S.E. ± 1.2) and nurse management (OR = −3.6, S.E. ± 1.6) had a significant negative association with emotional exhaustion, while hospital management and organizational support had a significant negative association with depersonalization (OR = −2.0, S.E. ± 0.8) [64] |

| Quantitative (nurses were invited to voluntarily complete questionnaires) [65] | 546 staff nurses from 42 units in four hospitals [65] | Emotional exhaustion is the strongest predictor of job satisfaction (OR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.85–0.94). Positive ratings on the nurse work practice environment dimensions including nurse-physician relations (Slope = −4, SE ± 0.7, Slope = −1.3, SE ± .4, Slope = 2.2, SE ± 0.5), nurse management (Slope = −8.5, SE ± 1.2, Slope = −3.1, SE ± 0.6, Slope = 4.32, SE ± 0.8) as well as hospital management and organizational support (Slope = −9.5, SE ± 1.1, Slope = −3.9, SE ± 0.6, Slope = 4.7, SE ± 0.8) were significantly correlated with lower emotional exhaustion and depersonalization as well as high personal accomplishment respectively. Hospital management and organizational support is significantly associated with job satisfaction (OR = 10.7, 95% CI 3.1–37) [65] |

| Quantitative (fieldworkers appointed by hospital management for private hospitals and by the affiliated university for public hospitals were trained to distribute and collect questionnaires) [66] | 935 registered nurses working in critical care units of selected private and public hospitals [66] | Significant correlations were found for all the subscales of the practice environment (including nurse manager leadership, ability and support, nurse physician relations, staffing and resource adequacy, nurse participation in hospital affairs) with job satisfaction (rs = 0.30 to .65, p < 0.01) and burnout (rs = −0.41 to 0.26, p < 0.01). Job satisfaction was also significantly associated with burnout (rs = −0.46 to 0.23, p < 0.01) [66] |

| Quantitative (surveys were mailed to nurses who were members of the Board of Nursing) [7] | 10,184 staff nurses providing adult acute care at 210 general hospitals [7] | An increase of one patient per nurse was found to increase burnout by 1.23 (95% CI, 1.13–1.34) and job dissatisfaction by 1.15 (95% CI, 1.07–1.25) confirming an association between these variables. Nurses working in hospitals with 1:8 patient ratios were found to be 2.29 times more likely to experience burnout and 1.75 times more likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs. Lower staffing increases the likelihood of nurses experiencing burnout and job dissatisfaction [7] |

3.5. Work Related Stress, Burnout and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (distribution of survey packets by head nurses/charge nurses) [67] | 237 paid staff nurses employed on 18 units in 7 hospitals [67] | More health complaints (anxiety, depression and somatization) were associated with higher work related stress and emotional exhaustion (rs = 0.21 to .42, p < 0.001). Work related stress, burnout and health are related [67] |

| Quantitative (questionnaires were sent to nurses’ home address) [68] | 69 nurses from anursing home [68] | High physical demands had adverse effects on physical complaints (β = 0.2, SE ± 0.1) and emotional demands affected emotional exhaustion (β = 0.4, SE ± 0.1) [68] |

| Quantitative (self reported questionnaire distribution) [69] | 1,636 unionized registered nurses (RNs) working in the public health care sector [69] | Demands including overload (γ = 0.57, p < 0.001), role stress (γ = 0.08, p < 0.05), hostility with physicians (γ = 0.12, p < 0.001) and hostility with patients (γ = 0.11, p < 0.01) are the most significantly important determinants of emotional exhaustion which indirectly affect depersonalization via emotional exhaustion (γ = 0.36, p < 0.001). Emotional exhaustion (γ = 0.71, p < 0.001) and depersonalization (γ = 0.22, p < 0.001) are significantly associated with psychosomatic complaints [69] |

| Quantitative (All of the centers were sent questionnaires for each one of their nurses) [70] | 229 professional nurses from medical centers [70] | High emotional exhaustion was found to be directly associated with physical tiredness (OR = 2.01; 95% CI, 1.12–3.61) and health (OR = 1.47; 95% CI, 1.32–1.63). High depersonalization was found to be associated with health (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.07–1.28). Low personal accomplishment was found to be inversely related to losing a patient (OR = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22–0.97) and lack of free time (OR = 0.43, 95% CI, 0.20–0.93). Physical tiredness and working with demanding patients are associated with burnout. Burnout is associated with poor health [70] |

| Quantitative (questionnaires were sent to nurses) [71] | 297 nurses at a large university hospital [71] | Nursing stress was directly associated with burnout as well as health (affective and physical symptoms), whereby nursing stress predicted burnout which predicted affect and physical symptoms (x² = (3, n = 259) = 19.07 (RMSR = 0.05, CFI = 0.92). Burnout was confirmed as an intervening variable between work stress and affective and physical symptomatology (x² = (1, n = 259) = 5.45 (RMSR = 0.01, CFI = 0.98) [71] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by nurse managers) [72] | 126 registered nurses were recruited from area hospitals [72] | Emotional exhaustion (R2 = −0.407; p < 0.0001) and depersonalization (R2 = −0.034; p < 0.05) were inversely predictive of health outcomes whereas personal accomplishment (R2 = 0.03; p < 0.05) was positively predictive of health outcomes. Work stress is indirectly related to burnout (through mediation by hardiness) and burnout is directly related to health outcomes [72] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution followed by reminders) [73] | 1,891 nurses from 6 acute care hospitals [73] | Work stress was significantly associated with burnout (OR = 5.77; 95% CI, 3.92–8.5) and mental health (OR = 2.34; 95% CI, 1.62–3.36) [73] |

3.6. Work Related Stress, Job Satisfaction and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution to nurses) [74] | 475 senior nurses [74] | Stressors accounted for the largest portion of the variance explaining job satisfaction (career stress = 22% and organizational stress = 3%). Job stress was found to be significantly predictive of job satisfaction (F (6, 468) = 31.8, p < 0.001). Only stress associated with workload was found to be a predictor of mental health (accounting for 4% of the variance) [74] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution to nurses) [75] | 561 trained staff nurses from 16 randomly chosen hospitals [75] | Various work dimensions such as job complexity, feedback/clarity, work pressure, autonomy, promotion/growth as well as supervisors’ leadership style are related to job satisfaction (r = 0.18–0.61, p < 0.01) and health complaints (r = 0.20–0.34, p < 0.01). 59% and 20% of variance in job satisfaction and health complaints is explained by the selected predictors (work dimensions) [75] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution to nurses) [74] | 475 senior nurses [74] | Stressors accounted for the largest portion of the variance explaining job satisfaction (career stress = 22% and organizational stress = 3%). Job stress was found to be significantly predictive of job satisfaction (F (6, 468) = 31.8, p < 0.001). Only stress associated with workload was found to be a predictor of mental health (accounting for 4% of the variance) [74] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution to nurses) [75] | 56l trained staff nurses from 16 randomly chosen hospitals [75] | Various work dimensions such as job complexity, feedback/clarity, work pressure, autonomy, promotion/growth as well as supervisors’ leadership style are related to job satisfaction (r = 0.18–0.61, p < 0.01) and health complaints (r = 0.20–0.34, p < 0.01). 59% and 20% of variance in job satisfaction and health complaints is explained by the selected predictors (work dimensions) [75] |

| Quantitative (following invitation and awareness questionnaires were distributed) [76] | 155 nurses from nine units in two general hospitals [76] | Autonomy and workload are significantly associated with job satisfaction (r = 0.46, p < 0.01 and r = −0.33, p < 0.01, respectively) and health complaints (r = −0.17, p < 0.05 and r = 0.25, p < 0.01, respectively). The correlation between complexity of care and job satisfaction was no longer significant (p = 0.38) when workload was corrected for. Workload mediates the relationship between complexity and job satisfaction [76] |

| (Quantitative (questionnaire distribution for completion at own convenience) [77] | 376 female hospital nurses working full time at an urban university teaching hospital [77] | In descending order, perceived relations with the head nurse (β = 0.24, p ≤ 0.001), job conflict (β = −0.19, p ≤ 0.001), relations with coworkers (β = 0.17, p ≤ 0.01), relations with physicians (β = 0.15, p ≤ 0.01), and other units/departments (β = 0.13, p ≤ 0.01) were significant predictors of job satisfaction. Job conflict (β = 0.12, p ≤ 0.05), along with the relations with the head nurse (β = −0.12, p ≤ 0.05) and physicians (β = 0.09, p ≤ 0.05), were predictors of psychological distress. The relations with the head nurse and physicians as well as job conflict, were predictors of both satisfaction and health [77] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution) [78] | 299 staff working in different forms of elderly care [78] | Stressors including workload, cooperation, age, expectations and demands, personal development and internal motivation explained 41% of the variance in perceived stress symptoms. Job satisfaction was positively and significantly associated with perceived stress symptoms including sleep disturbance, depression, headaches and stomach disorders. This model was significant (F(6/280) = 32.54, p < 0.001) [78] |

| Quantitative (self administered questionnaire distribution) [79] | 218 female nurses from public hospitals [79] | Nurses with the highest level of stress reported significantly higher frequency of tension headache (32.4%, p < 0.001), back-pain (30.1%, p < 0.05), sleeping problems (37%, p < 0.001), chronic fatigue (59.5%, p < 0.001), stomach acidity (31.5%, p < 0.01) and palpitations (32.4%, p < 0.01). The frequency of psychosomatic symptoms is an indicator of nurse related stress. No relationship was confirmed between job satisfaction and stress [79] |

| Quantitative (distribution of self administered structured surveys) [80] | 254 nurses working in 15 emergency departments of general hospitals [80] | Work-time demands were found to be important determinants of psychosomatic complaints (β = −0.31, p < 0.001) and fatigue (β = −0.21, p < 0.01) in emergency nurses. Decision authority (β = 0.138, p < 0.05), skill discretion (β = 0.17, p < 0.01), perceived reward (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) and social support by colleagues (β = 0.16, p < 0.01) were found to be strong determinants of job satisfaction. Work related stress explained 21% of the variance in psychosomatic complaints and 34% variance in job satisfaction [80] |

3.7. Burnout and Job Satisfaction

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by administrative officer) [81] | 248 nurses from five hospitals [81] | Satisfaction with supervisors and coworkers was significantly negatively associated with emotional exhaustion (r = −0.50, p < 0.01 and r = −0.34, p < 0.01, respectively) and depersonalization (r = −0.41, p < 0.01 and r = −0.29, p < 0.01, respectively) while being positively correlated with personal accomplishment (r = 0.19, p < 0.01 and r = 0.19, p < 0.01, respectively). This two-factor model compared to the single-factor model was a better fit (Δχ² (1) = 572.533, p < 0.001) [81] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution in a quiet room within the hospital) [11] | 203 employed nurses [11] | Through path analyses, it was found that job satisfaction had a direct negative effect on emotional exhaustion (−0.97, p < 0.01) and on depersonalization through emotional exhaustion (−0.58, p < 0.01). Job satisfaction is a significant predictor of burnout in nurses [11] |

3.8. Burnout and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (anonymous distribution of self reported questionnaires) [82] | 368 members of the nursing staff [82] | A weak but significant relationship between burnout and depression was found (χ² (3) = 12.093, p < 0.01) Younger nurses were found to suffer from burnout and depression (χ² (3) = 13.337, p > 0.01), more than elderly nurses (χ²(3) = 5.685, p < 0.01) [82] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution and collection in one sitting) [83] | 17 male and 62 female nurses in general internal medicine, general surgery and respiratory medical wards [83] | Depression was correlated with burnout to a lesser degree (r = −0.38 to 0.27, p < 0.05) than sense of coherence (r = −0.55 to 0.44, p < 0.05), which was correlated to a higher degree with depression (r = −0.58, p < 0.05). The relationship between burnout and depression may be a product of the relationship between depression and sense of coherence [83] |

3.9. Burnout, Job Satisfaction and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution) [84] | 239 nurses in Japan and 550 nurses in mainland China [84] | Job satisfaction among Japanese nurses was found to be a significant predictor of depersonalization (ΔR² = 0.22, p < 0.001; β = −0.21, p < 0.01), diminished personal accomplishment (ΔR² = 0.10, p < 0.001; β = −0.28, p < 0.01), and depression (ΔR² = 0.37, p < 0.001; β = −0.30, p < 0.001). Among Chinese nurses job satisfaction also significantly predicted depersonalization (ΔR² = 0.11, p < 0.001; β = −0.12, p < 0.05), diminished personal accomplishment (ΔR² = 0.08, p < 0.001; β = −0.25, p < 0.001), and depression (ΔR² = 0.24, p < 0.001; β = −0.18, p < 0.001). Emotional exhaustion was found to significantly predict depression in Japanese (ΔR² = 0.37, p < 0.001; β = 0.43, p < 0.001) as well as Chinese nurses (ΔR² = 0.24, p < 0.001; β = 0.38, p < 0.001). Absenteeism was not significantly predictive of burnout or job satisfaction. Job satisfaction was found to moderate the relationship between emotional exhaustion and absenteeism in predicting depression among Japanese (ΔR² = 0.03, p < 0.01; β = −3.9, p < 0.01) and Chinese nurses (ΔR² = 0.02, p < 0.05; β = −4.2, p < 0.05) [84] |

3.10. Job Satisfaction and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative and qualitative (following a medical pre-examination of mental health as well as interviews about shifts/tasks, questionnaires were distributed to eligible participants) [85] | 101 nurses enrolled at a clinic of occupational medicine [85] | Increase in job satisfaction was associated with decreased psychological distress measured using several indicators including perceived stress (r = −0.44, p < 0.05) and general health (r = −0.24, p < 0.05) scores. Job satisfaction is inversely associated with reduced psychological distress [85] |

3.11. Work Related Stress, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and General Health

| Method | Sample | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative (structure questionnaires were mailed with nurses’ paychecks) [23] | 173 nurses [23] | Job stress was significantly associated with burnout (r = 0.56, p < 0.01) and job satisfaction (r = −0.34, p < 0.01). Job stress was significantly associated with psychosomatic health problems (r = 0.55, p < 0.01). The only significant interaction was found between job stress and psychosomatic health problems accounting for 5% of the variance (p < 0.05) [23] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution following invitation letters) [86] | 1,204 nurses working in general hospitals [86] | The variance explaining job satisfaction was high (R² = 0.44). High job satisfaction was significantly (p < 0.05) predicted by high social support (β = 0.33), low workload (β = −0.21), low role ambiguity (β = −0.19), low role conflict (β = −0.14) and high autonomy (β = 0.09). Psychosomatic health complaints were explained by high workload (β = 0.20, p < 0.05); low social support (β = −0.10, p < .05), and high role conflict (β = 0.09, p < 0.05). A two-way interaction effect was found between workload and social support (β = −0.08) thereby suggesting that higher levels of social support buffer the negative effects of workload on emotional exhaustion. Results also indicated that high levels of social support would buffer the negative effects of workload on job satisfaction (β = 0.08, p < 0.05). High complexity was indirectly predictive of burnout (ΔR² = 0.01, p < 0.05; β = −0.08, p < 0.05) through mediation by workload (ΔR² = 0.29, p < 0.05; β = 0.37, p < 0.05) [86] |

| Quantitative (questionnaires were sent to nurses’ home address) [88] | The sample consisted of 807 registered nurses working in an academic hospital [88] | Organizational and environmental conditions explained significant variance in job characteristics, ranging between 14% in social support colleagues and 41% in workload. Job characteristics explained significant variance in outcomes, ranging between 13% in somatic complaints and 38% in job satisfaction whereas organizational/ environmental conditions explained significant variance in all outcomes: 4% in somatic complaints, 5% in psychological distress, 11% in emotional exhaustion, and 26% in job satisfaction. Occupational stressors overall predict large amounts of the variance in the outcome measures, especially in job satisfaction (44%) and emotional exhaustion (25%). In conclusion, job characteristics (job stressors) mediate the relationship between organisational and environmental conditions and outcomes (burnout, job satisfaction and health) [88] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire administration) [87] | 1,697 registered nurses [87] | Increase in job satisfaction was predicted by emphasis on patient care, recognizing importance of personal lives, satisfaction with salary/benefits, job security and positive relationships with other nurses and managers. Decrease in job satisfaction was predicted by high levels of stress to the point of burnout. Physical health predicted satisfaction with nursing as a career [87] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution with instructions to return by mail) [89] | 175 nurses working in a psychiatric hospital [89] | Job satisfaction was moderately associated with burnout (r = −0.56, p < 0.05), which was also moderately associated with psychosomatic health problems (r = 0.45, p < 0.05). With shift time as a stressor, significant differences were found in psychosomatic health problems between day and evening shifts (t = 2.2, p < 0.05), evening and rotational shifts (t = −2.3, p < 0.05) as well as night and rotational shifts (t = −2.10, p < .05). For job satisfaction, significant differences were found between day and night shifts (t = 2.97, p < .05), evening and night shifts (t = 2.68, p < 0.05) as well as rotational and night shifts (t = 3.13, p < 0.05). Generally, night shift nurses’ wellbeing seemed to be affected more seriously than nurses working other shifts. Only one interaction effect was found to be significant leading to the conclusion that female nurses on rotating shift experience more health problems than other nurses (F = 3.85, p < 0.05) [89] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution with letter explaining the study) [90] | 404 nurses ( 77 male and 317 female) [90] | Job characteristics reflected emotional exhaustion (r = −0.17 to −0.38, p < 0.001) but did not explain it. Emotional exhaustion was most highly correlated with job satisfaction (r = −0.55, p < 0.001). Both emotional exhaustion (r = 0.25, p < 0.001) and job satisfaction (r = −0.12, p < 0.05) were related to sickness absence. Job satisfaction was found to be a strong predictor of emotional exhaustion (β = −0.42, p = 0.001). The most prominent predictor of sickness absence was emotional exhaustion (β = 0.29, p = 0.001) [90] |

| Quantitative (questionnaire distribution by the matron and researchers in each ward) [91] | 309 female nurses working in private and public hospitals in 3 countries [91] | Burnout is most strongly predicted by problems with information provision (ΔR² = 0.17, p < 0.001; β = −0.20, p < 0.001), job satisfaction by lack of social support form supervisors (ΔR² = 0.36, p < 0.001; β = 0.21, p < 0.001) and somatic complaints by physical working conditions (ΔR² = 0.08, p < 0.01; β = 0.16, p < 0.05) [91] |

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Occup. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory: Manual, 2nd ed; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Vanyperen, N.W.; Buunk, B.P.; Schaufeli, W.B. Communal orientation and the burnout syndrome among nurses. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: The Cost of Caring; Malor Books: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 25–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, S.S.; Sotile, W.M.; Sotile, M.O. Physician burnout. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004, 291, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, R.E; Johnson-Leong, C. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among dentists. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 788–794. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Sochalski, J.; Silber, J. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 288, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, M.; Bester, C.L.; Van Den Berg, H.; Van Rensburg, H.C.J. The Prediction of Psychological Burnout by Means of the Availability of Resources, Time Pressure or Workload, Conflict and Social Relations and Locus of Control of Professional Nurses in Public Health Centres in the Free State. In proceedings of the European Applied Business Conference (EABR) and Teaching and Learning Conference (TLC), Rothenburg, Germany, 8–11 June 2008.

- Jennings, B.M. Work Stress and Burnout among Nurses: Role of the Work Environment and Working Conditions. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence Based Handbook for Nurses; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Levert, T.; Lucas, M.; Ortlepp, K. Burnout in psychiatric nurses: Contributions of the work environment and a sense of coherence. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2000, 30, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliath, T.; Morris, R. Job satisfaction among nurses: A predictor of burnout levels. J. Nurs. Admin. 2002, 32, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, J.M. Stress in Nursing Care. In Alzheimer’s Disease: A Handbook for Caregivers, 2nd; Hamdy, R.C., Turnbull, J.M., Clark., W, Lancaster, M.M., Eds.; Mosby: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 319–327. [Google Scholar]

- Demeuroti, F.; Bakker, A.R.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. A model of burnout and life satisfaction among nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 454–464. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Bogossian, F.; Ahern, K. Stress and coping in Australian nurses: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2010, 57, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, P.; Smojkis, M. The mental health of nurses in the UK. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2003, 9, 374–379. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D.; Edwards, D.; Hannigan, B.; Fothergill, A.; Burnard, P. A systematic review of stress among mental health social workers. Int. Soc. Work 2005, 48, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, J.M.; Munz, D.C.; Grawitch, M.J. Test of a dynamic stress model for organisational change: Do males and females require different models? Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2006, 55, 168–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Mashego, T.; Mabeba, M. Short communication: Occupational stress and burnout among South African medical practitioners. Stress Health 2003, 19, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmann, S.; Van Der Colff, J.J.; Rothmann, J.C. Occupational stress of nurses in South Africa. Curationis 2006, 29, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Barriball, K.L.; Zhang, X; While, A.E. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses revisited: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1017–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.G.; Ang, E.; Devi, M.K. Systematic review on the relationship between the nursing shortage and job satisfaction, stress and burnout levels among nurses in oncology/haematology settings. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2012, 10, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony, N. Nurse burnout and the working environment. Emerg. Nurse 2011, 19, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, M.; Baba, V.V. Job stress and burnout among Canadian managers and nurses: An empirical examination. C. J. Public Health 2000, 91, 454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Hillier, V.F. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol. Med. 1979, 9, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chayu, T.; Kreitler, S. Burnout in nephrology nurses in Israel. Nephrol. Nurs. J. 2011, 38, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.Y.; Akhtar, S. Effects of the workplace social context and job content on nurse burnout. Hum. Resource Manage. 2011, 50, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ohue, T.; Moriyama, M.; Nakaya, T. Examination of a cognitive model of stress, burnout and intention to resign for Japanese nurses. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2011, 8, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, M.E.W.; Van Den Berg, A.A.; Halfens, R.; Huyer Abu-Saad, H.; Philipsen, H.; Gassman, P. Burnout and the work environment of nurses in psychiatric long-stay care settings. Soc. Psych. Psych. Epid. 1997, 32, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, M. Burnout and AIDS care related factors in HIV community nurse specialists. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 29, 984–993. [Google Scholar]

- Garrosa, E.; Rainho, C.; Moreno-Jimenez, B.; Monteiro, M.J. The relationship between job stressors, hardy personality, coping resources and burnout in a sample ofnurses: A correlational study at two time points. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gueritault-Chalvin, V.; Kalichman, S.C.; Demi, A.; Peterson, J.L. Work-related stress and occupational burnout in AIDS caregivers: Test of a coping model with nurses providing AIDS care. AIDS Care 2000, 12, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, K.; Lavery, J.F. Burnout in nursing. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 24, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Lan, Y. Relationship between burnout and occupational stress among nurses in China. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 59, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, D.; Street, A.; Love, A.W. Relationships between stressors, work supports and burnout among cancer nurses. Cancer Nurs. 2006, 29, 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Lasebikan, V.O.; Oyetunde, M.O. Burnout among nurses in a Nigerian general hospital: Prevalence and associated factors. ISRN Nurs. 2012, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, C. Job satisfaction among neonatal nurses. Pediatr. Nurs. 2006, 32, 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, M.; Franco, M.; Messmer, P.R.; Gonzalez, J.L. Practice applications of research. Nurses’ job satisfaction, stress and recognition in a pediatric setting. Pediatr. Nurs. 2004, 30, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, K.; Stewart, N.J.; D’Arcy, C.; Morgan, D. Predictors of job satisfaction for rural acute care registered nurses in Canada. Western J. Nurs. Res. 2008, 30, 785–800. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, A.; Fowler, S.; Fiedler, N.; Osinubi, O.; Robson, M. The impact of environmental factors on nursing stress, job satisfaction and turnover intention. J. Nurs. Admin. 2010, 40, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Chaboyer, W.; Williams, G.; Corkill, W.; Creamer, J. Predictors of job satisfaction in remote hospital nursing. Can. J. Nurs. Leadersh. 1999, 12, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Djukic, M.; Kovner, C.; Budin, W.C.; Norman, R. Physical work environment: Testing an expanded model of job satisfaction in a sample of registered nurses. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulou, K.K.; While, A.E. Professional autonomy and job satisfaction: Survey of critical care nurses in mainland Greece. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2520–2531. [Google Scholar]

- Malliarou, M.; Sarafis, P.; Moustaka, E.; Kouvela, T.; Constantinidis, T.C. Greek registered nurses’ job satisfaction in relation to work-related stress. A study on army and civilian RNs. Global J. Health Sci. 2010, 2, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, K.; Davies, B.; Woodend, K.; Simpson, J.; Mantha, S. Impacting Canadian public health nurses’ job satisfaction. C. J. Public Health 2011, 102, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, C.; McKay, M.F. Nursing stress: The effects of coping strategies and job satisfaction in a sample of Australian nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 681–688. [Google Scholar]

- Zurmehly, J. The relationship of educational preparation, autonomy, and critical thinking to nursing job satisfaction. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2008, 39, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzer, M.; Wojtaszczyk, A.M.; Kelly, J. Nurses’ perceptions of physicians’ communication: The relationship among communication practices, satisfaction and collaboration. Health Commun. 2009, 24, 683–691. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, W.H.; Chang, C.S.; Shih, Y.L.; Liang, R.D. Effects of job rotation and role stress among nurses on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, N.A.; Flanagan, T.J. An analysis of the relationship between job satisfaction and job stress in correctional nurses. Res. Nurs. Health 2002, 25, 282–294. [Google Scholar]

- Larrabee, J.H.; Wu, Y.; Persily, C.A.; Simoni, P.S.; Johnston, P.A.; Marcischak, T.L.; Mott, C.L.; Gladden, S.D. Influence of stress resiliency on RN job satisfaction and intent to stay. Western J. Nurs. Res. 2010, 32, 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi, J.; Markham, F.; Bounds, W. Factors related to nurse retention and turnover: An updated study. Health Mark. Q. 1998, 15, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Piko, B.F. Psychosocial work environment and psychosomatic health of nurses in Hungary. WorkStress 2003, 17, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.C.; Huang, C.C.; Wu, C.C. Association between stress at work and primary headache among nursing staff in Taiwan. Headache 2007, 47, 576–584. [Google Scholar]

- Malinauskienė, V.; Leišytė, P.; Malinauskas, R. Psychosocial job characteristics, social support, and sense of coherence as determinants of mental health among nurses. Med. Lith. 2009, 45, 910–917. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, V.A.; Lambert, C.E.; Petrini, M.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, Y.J. Predictors of physical and mental health in hospital nurses within the People’s Republic of China. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2007, 54, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Boey, K.W.; Chan, K.B.; Ko, Y.C.; Goh, C.G.; Lim, G.C. Work stress and psychological well-being among nursing professionals in Singapore. Singap. Med. J. 1997, 38, 256–260. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, S.J.; Harris, M.R.; Pipe, T.B.; Stevens, S.R. Nurses’ ratings of their health and professional work environments. Am. Assoc. Occ. Health Nurses J. 2010, 58, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.D.; Kutney-Lee, A.; Cimiotti, J.; Sloane, D.M.; Aiken, L.H. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Affair. 2011, 2, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; You, L.M.; Chen, S.X.; Hao, Y.T.; Zhu, X.W.; Zhang, L.F.; Aiken, L.H. The relationship between hospital work environment and nurse outcomes in Guangdong, China: A nurse questionnaire survey. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Kiekkas, P.; Spyratos, F.; Lampa, E.; Aretha, D.; Sakellaropoulos, G.C. Level and correlates of burnout among orthopaedic nurses in Greece. Orthop. Nurs. 2010, 29, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.H.; June, K.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Cho, Y.A.; Yoo, C.S.; Yun, S.C.; Sung, Y.H. Nurse staffing, quality of nursing care and nurse job outcomes in intensive care units. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar]

- Sheward, L.; Hunt, J.; Hagen, S.; Macleod, M.; Ball, J. The relationship between UK hospital nurse staffing and emotional exhaustion and job dissatisfaction. J. Nurs. Manage. 2005, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, P.V.; Meulemans, H.; Clarke, S.; Vermeyen, K.; van de Heyning, P. Hospital nurse practice environment, burnout, job outcomes and quality of care: Test of a structural equation model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, P.V.; Clarke, S.; Vermeyen, K.; Meulemans, H.; van de Heyning, P. Practice environments and their associations with nurse-reported outcomes in Belgian hospitals: Development and preliminary validation of a Dutch adaptation of the Revised Nursing Work Index. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, P.V.; Clarke, S.; Roelant, E.; Meulemans, H.; van de Heyning, P. Impacts of unit-level nurse practice environment and burnout on nurse-reported outcomes: A multilevel modelling approach. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Klopper, H.C.; Coetzee, S.K.; Pretorius, R.; Bester, P. Practice environment, job satisfaction and burnout of critical care nurses in South Africa. J. Nurs. Manage. 2012, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar]

- van Servellen, G.; Topf, M.; Leake, B. Personality hardiness, work-related stress, and health in hospital nurses. Hosp. Top. 1994, 72, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tooren, M.; de Jonge, J. Managing job stress in nursing: What kind of resources do we need? J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 63, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, G.; Chenevert, D. Job demands-resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: A questionnaire study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 709–722. [Google Scholar]

- Bressi, C.; Manenti, S.; Porcellana, M.; Cevales, D.; Farina, L.; Felicioni, I.; Meloni, G.; Milone, G.; Miccolis, I.R.; Pavanetto, M.; et al. Haemato-oncology and burnout: An Italian survey. Brit. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillhouse, J.J.; Adler, C. Evaluating a simple model of work, stress, burnout, affective and physical symptoms in nurses. Psychol. Health Med. 1996, 1, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortet, J.; Banks, S. Hardiness, job stress and health in nurses. Hosp. Top. 1996, 74, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bourbonnais, R.; Comeau, M.; Vézina, M.; Dion, G. Job strain, psychological distress, and burnout in nurses. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1998, 34, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglioni, A.J., Jr.; Cooper, C.L.; Hingley, P. Job stress, mental health and job satisfaction among U.K. senior nurses. Stress Med. 1990, 6, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landerweerd, J.A.; Boumans, N.P.G. The effect of work dimensions and need for autonomy on nurses’ work satisfaction and health. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 1994, 67, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, G.E.R.; Landeweerd, J.A.; Merode, G.V. Organization, work and work reactions: A study of the relationship between organizational aspects of nursing and nurses’ work characteristics and work reactions. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2002, 16, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, F.H. Occupational and non occupational factors in job satisfaction and psychological distress among nurses. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, M.; Ljunggren, B.; Lindqvist, R.; Carlsson, M. Staff satisfaction with work, perceived quality of care and stress in elderly care: Psychometric assessments and associations. J. Nurs. Manage. 2006, 14, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piko, B.F. Work related stress among nurses: A challenge for health care institutions. J. R. Soc. Promo. Health 1999, 119, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens, J.; Gucht, V.M.J.; Doef, M.P.; Maes, S. Exploring the burden of emergency care: Predictors of stress-health outcomes in emergency nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, C.; Basim, N. Examination of developmental models of occupational burnout using burnout profiles of nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 64, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovides, A.; Fountoulakis, K.N.; Moysidou, C.; Ierodiakonou, C. Burnout in nursing staff: Is there a relationship between depression and burnout? Int. J. Psychiat. Med. 1999, 29, 421–433. [Google Scholar]

- Tselebis, A.; Moulou, A.; Ilias, I. Burnout versus depression and sense of coherence: Study of Greek nursing staff. Nurs. Health Sci. 2001, 3, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny, L.; Baba, V.V.; Wang, X. Burnout and depression among nurses in Japan and China: The moderating effects of job satisfaction and absence. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2010, 21, 2741–2761. [Google Scholar]

- Amati, M.; Tomasetti, M.; Ciuccarelli, M.; Mariotti, L.; Tarquini, L.M.; Bracci, M.; Baldassari, M.; Balducci, C.; Alleva, R.; Borghi, B.; et al. Relationship of job satisfaction, psychological distress and stress-related biological parameters among healthy nurses: A longitudinal study. J. Occup. Health 2010, 52, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, G.E.R.; Landeweerd, J.A.; van Merode, G.G. Work organization, work characteristics and their psychological effects on nurses in the Netherlands. Int. J. Stress. Manage. 2002, 9, 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Buerhaus, P.I.; Donelan, K.; Ulrich, B.T.; Kirby, L.; Norman, L.; Dittus, R. Registered nurses’ perceptions of nursing. Nurs. Econ. 2005, 23, 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gelsema, T.I.; van Doef, M.; Maes, S.; Akerboom, S.; Verhoeven, C. Job stress in the nursing profession: The influence of organizational and environmental conditions and job characteristics. Int. J. Stress Manage. 2005, 12, 222–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, M.; Baba, V.V. Shiftwork, burnout and well-being: A study of Canadian nurses. Int. J. Stress Manage. 1997, 4, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, M.H.J.; Croon, M.A.; Bressers, B. Childcare involvement, job characteristics, gender and work attitudes as predictors of emotional exhaustion and sickness absence. Work Stress 2005, 19, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Doef, M.; Mbazzi, F.B.; Verhoeven, C. Job conditions, job satisfaction, somatic complaint and burnout among East African nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. The Truth About Burnout: How Organisations Cause Personal Stress and What To Do About It; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, D.; Severance, S.; Feldstein, A. The Effect of Health Care Working Conditions on Patient Safety; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Khamisa, N.; Peltzer, K.; Oldenburg, B. Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 2214-2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10062214

Khamisa N, Peltzer K, Oldenburg B. Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013; 10(6):2214-2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10062214

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhamisa, Natasha, Karl Peltzer, and Brian Oldenburg. 2013. "Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 6: 2214-2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10062214

APA StyleKhamisa, N., Peltzer, K., & Oldenburg, B. (2013). Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(6), 2214-2240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10062214