Lead in School Children from Morelos, Mexico: Levels, Sources and Feasible Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment of Participants

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Laboratory Analysis

2.5. Determination of Lead in the Environment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

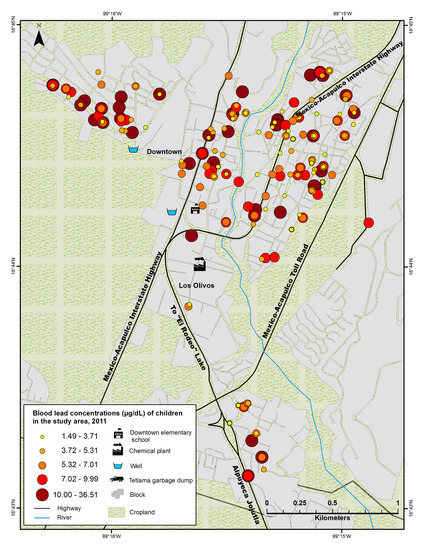

2.7. Geo Spatial Analysis

2.8. Study Approval

3. Results

| Potential Sources or Risk Factors for Higher Blood Lead Levels (%) | Mean Blood Lead Level (µg/dL) | Mean Blood Lead Difference Comparing to Reference Group (µg/dL) | T-Test P(t) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex (47) | 7.57 | 0.69 | 0.29 |

| Exposed to second-hand smoke at home (37) | 6.82 | −0.69 | 0.31 |

| Food is cooked in lead glazed ceramics at home (48) | 7.98 | 1.4 | 0.03 |

| Food is stored in lead glazed ceramics at home (12) | 9.29 | 2.39 | 0.02 |

| Eats potentially lead-contaminated candies (84) | 7.29 | 0.38 | 0.66 |

| Pica (soil, paint, pencils or chalk) (55) | 7.23 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| No flooring within the house (bare soil) (26) | 8.00 | 1.04 | 0.16 |

| Painted walls in the house (47) | 6.55 | −1.34 | 0.05 |

| No tap water available in the house (53) | 7.06 | −0.4 | 0.55 |

| Home located in poorest neighborhoods (53) | 7.28 | 0.11 | 0.87 |

| Attends afternoon school shift (56) | 7.65 | 1.55 | 0.28 |

| Possible para-occupational exposure to lead (18) | 7.02 | −0.26 | 0.76 |

| Sampled Medium | Location and Number of Samples | Sampling Date | Lead Concentrations in Medium | Reference Values of Medium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Soil | Soccer field in downtown elementary school (N = 3) | April 2011 | 5.73, 54.43 mg/kg | 28.80 (15.3) mg/kg | Mexican Official Norm for agricultural, commercial and residential use = 400 mg/kg [41] |

| Playground in both elementary schools (N = 3) | April 2012 | 10.95, 46.62 mg/kg | 24.69 (13.7) mg/kg | EPA for play areas= 400 mg/kg (US EPA, 2001) [42] | |

| Front or back yard of homes corresponding to children with the highest BPb levels (N = 13) | April 2012 | 8.22, 37.47 mg/kg | 18.05 (8.1) mg/kg | ATSDR defines non-polluted soil <50 ppm [43] | |

| Dust | Windowsills and furniture of homes corresponding to children with the highest BPb levels (N = 13) | April 2012 | 10.85, 99.69 mg/kg | 43.16 (31.9) | Not available |

| Sediment | Alpuyeca’s dam (N = 3) | April 2012 | 1.97–17.24 mg/kg | 12.32 (4.7) mg/kg | Not available |

| Alpuyeca’s river (N = 3) | April 2012 | 6.09–7.32 mg/kg | 6.77 (0.6) mg/kg | ||

| Water | Stored tap water from study homes (N = 17), bottled water (N = 17) and superficial water in a recreational area of the river (N = 3) | April 2011 | All below detection limit = 0.005 mg/L | below detection limit | EPA’s action level = 0.015 mg/L [44] |

| Mexican Official Norm for water use and consumption (NOM-127-SSA1-1994) = 0.01 mg/L [45] | |||||

| Non-glazed ceramics | Cuentepec street market (N = 3) | October 2012 | Detection limit: 0.04 mg/Kg | 8.75 (0.04) mg/Kg of total lead | Not available |

| Cuentepec street market (N = 3) | December 2012 | All below detection limit: <0.010 mg Pb/L acetic acid solution | Below detection limit: <0.010 mg Pb/L acetic acid solution | Mexican Official Norm for glazed ceramics= 0.5 Pb to 2 mg/L acetic acid solution [46] | |

| Glazed ceramics | Alpuyeca street market (N = 3) | October 2012 | Detection limit: 0.04 mg/Kg | 27.50 (0.06) mg/Kg of total lead | Not available |

| Alpuyeca street market (N = 3) | December 2012 | 38.23, 278.72 mgPb/L acetic acid solution | 198.19 mg/L | Mexican Official Norm for glazed ceramics= 0.5 to 2 mg Pb/L acetic acid solution [46] | |

| Local candy | Six kinds of candy, ten pieces of each (N = 60) | October 2012 | <0.004 (detection limit), 0.176 ppm | 0.034 (0.01) ppm | FDA recommended maximum lead level of 0.1 ppm in candy likely to be consumed frequently by small children [47] |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

- Paulina Farías: statistical analysis, manuscript draft and final version.

- Urinda Álamo-Hernández: study design and manuscript draft.

- Leonardo Mancilla-Sánchez: data analysis and manuscript draft.

- José Luis Texcalac Sangrador: responsible for geo-spatial analysis.

- Leticia Carrizales-Yáñez: laboratory analysis and manuscript draft.

- Horacio Riojas–Rodríguez: study design, critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Bellinger, D.C.; Arroyo-Quiroz, C.; Lamadrid-Figueroa, H.; Mercado-García, A.; Schnaas-Arrieta, L.; Wright, R.O.; Hernández-Avila, M.; Hu, H. Longitudinal associations between blood lead concentrations lower than 10 microg/dL and neurobehavioral development in environmentally exposed children in Mexico City. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e323–e330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Needleman, H. Low level lead exposure: History and discovery. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnaas, L.; Rothenberg, S.J.; Flores, M.-F.; Martínez, S.; Hernández, C.; Osorio, E.; Perroni, E. Blood lead secular trend in a cohort of children in Mexico City (1987–2002). Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischitelli, G.; Nygren, P.; Bougatsos, C.; Freeman, M.; Helfand, M. Screening for elevated lead levels in childhood and pregnancy: An updated summary of evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1867–e1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, K.S. CDC updates guidelines for children’s lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, A.K.; Taylor, M.P.; Munksgaard, N.C.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Burn-Nunes, L. Identification of environmental lead sources and pathways in a mining and smelting town: Mount Isa, Australia. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 180, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Were, F.H.; Kamau, G.N.; Shiundu, P.M.; Wafula, G.A.; Moturi, C.M. Air and blood lead levels in lead acid battery recycling and manufacturing plants in Kenya. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2012, 9, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.E.; Clickner, R.P.; Zhou, J.Y.; Viet, S.M.; Marker, D.A.; Rogers, J.W.; Zeldin, D.C.; Broene, P.; Friedman, W. The prevalence of lead-based paint hazards in U.S. housing. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, A599–A606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanier, A.J.; Wilson, S.; Ho, M.; Hornung, R.; Lanphear, B.P. The contribution of housing renovation to children’s blood lead levels: A cohort study. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.L.; Gaitens, J.M.; Jacobs, D.E.; Strauss, W.; Nagaraja, J.; Pivetz, T.; Wilson, J.W.; Ashley, P.J. Exposure of U.S. children to residential dust lead, 1999–2004: II. The contribution of lead-contaminated dust to children’s blood lead levels. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuakuila, J.; Kabamba, M.; Mata, H.; Mata, G. Blood lead levels in children after phase-out of leaded gasoline in Kinshasa, the capital of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Arch. Public Health Arch. Belg. 2013, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus-García, A.; Ramos-Bonilla, J.P. Presence of lead in paint of toys sold in stores of the formal market of Bogotá, Colombia. Environ. Res. 2014, 128, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourmoradi, H.; Foroghi, M.; Farhadkhani, M.; Vahid Dastjerdi, M. Assessment of lead and cadmium levels in frequently used cosmetic products in Iran. J. Environ. Public Health 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgaied, J.-E. Release of heavy metals from Tunisian traditional earthenware. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2003, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary-Webb, M.; Paschal, D.C.; Romieu, I.; Ting, B.; Elliot, C.; Hopkins, H.; Sanín, L.H.; Ghazi, M.A. Determining lead sources in Mexico using the lead isotope ratio. Salud Pública México 2003, 45, S183–S188. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, J.; Albert, L.A. Environmental lead in Mexico, 1990–2002. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2004, 181, 37–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Bellinger, D.; Lanphear, B.; Grandjean, P.; International pooled lead study investigators. An international pooled analysis for obtaining a benchmark dose for environmental lead exposure in children. Risk Anal. Off. Publ. Soc. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, J.C.; Dowling, K.C.; Siegel, D.M.; Alexeeff, G.V. A blood lead benchmark for assessing risks from childhood lead exposure. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2009, 44, 1200–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATSDR—Toxicological Profile: Lead. 2007. Available online: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/TP.asp?id=96&tid=22 (accessed on 28 April 2014).

- WHO. Childhood Lead Poisoning. 2010. Available online: http://www.who.int/ceh/publications/childhoodpoisoning/en/ (accessed on 28 April 2014).

- Gump, B.B.; Mackenzie, J.A.; Bendinskas, K.; Morgan, R.; Dumas, A.K.; Palmer, C.D.; Parsons, P.J. Low-level Pb and cardiovascular responses to acute stress in children: The role of cardiac autonomic regulation. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011, 33, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gao, D.; Chen, Y.; Jing, J.; Hu, Q.; Chen, Y. Lead exposure at each stage of pregnancy and neurobehavioral development of neonates. Neurotoxicology 2014, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fels, L.M.; Wünsch, M.; Baranowski, J.; Norska-Borówka, I.; Price, R.G.; Taylor, S.A.; Patel, S.; de Broe, M.; Elsevier, M.M.; Lauwerys, R.; et al. Adverse effects of chronic low level lead exposure on kidney function—A risk group study in children. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc.—Eur. Ren. Assoc. 1998, 13, 2248–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Doumouchtsis, K.K.; Doumouchtsis, S.K.; Doumouchtsis, E.K.; Perrea, D.N. The effect of lead intoxication on endocrine functions. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2009, 32, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, K.P.; Chauhan, U.K.; Naik, S. Effect of lead exposure on serum immunoglobulins and reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediate. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2006, 25, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, B.; Ritz, B.; Heinrich, J.; Hoelscher, B.; Wichmann, H.E. The effect of low-level blood lead on hematologic parameters in children. Environ. Res. 2000, 82, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Burdé, B.; Reames, B. Prevention of pica, the major cause of lead poisoning in children. Am. J. Public Health 1973, 63, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, E.E.; Edwards, B.B.; Jensen, R.L.; Mahaffey, K.R.; Fomon, S.J. Absorption and retention of lead by infants. Pediatr. Res. 1978, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahaffey, K.R. Nutritional factors and susceptibility to lead toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 1974, 7, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Valko, M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology 2011, 283, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; McCauley, L.; Compher, C.; Yan, C.; Shen, X.; Needleman, H.; Pinto-Martin, J.A. Regular breakfast and blood lead levels among preschool children. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda. Available online: http://www.censo2010.org.mx/ (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- Riojas-Rodríguez, H. Environmental Health in Alpuyeca, México. An Ecosystem Approach; The International Society for Environmenntal Epidemiology: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses-González, F.; Richardson, V.; Lino-González, M.; Vidal, M.T. Blood lead levels and exposure factors in children of Morelos state, Mexico. Salud Pública México 2003, 45, S203–S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, K.S. Performance of diammonium hydrogen phosphate-nitric acid-graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometric method for urinary cadmium determination. Clin Chem. 1987, 33. Available online: http://www.clinchem.org/content/33/7/1298.2.full.pdf (accessed on 21 July 1987).

- CONAGUA. Análisis de Agua-Determinación de Metales por Absorción Atómica en Aguas Naturales, Potables, Residuales y Residuales Tratadas-Método de Prueba (Water Analysis-Determination of Metals by Atomic Absorption in Water: Natural, Drinking, Wastewater and Treated Wastewater-Test Method); Consejo Nacional del Agua: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. Available online: http://www.mwa.co.th/download/file_upload/SMWW_10900end.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. Release 11; StataCorp.: Texas, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, P.C. Spatial Epidemiological Approaches in Disease Mapping and Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, C.D. Local Models for Spatial Analysis, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SEMARNAT. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-147-SEMARNAT/SSA1-2004. Available online: http://biblioteca.semarnat.gob.mx/janium/Documentos/Ciga/agenda/PP03/DO950.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Hazard Standards for Lead in Paint, Dust and Soil (TSCA Section 403). Available online: http://www2.epa.gov/lead/hazard-standards-lead-paint-dust-and-soil-tsca-section-403 (accessed on 2 October 2014).

- ATSDR. Lead (Pb) Toxicity: What Are the U.S. Standards for Lead Levels? ATSDR—Environmental Medicine & Environmental Health Education—CSEM. Available online: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=7&po=8 (accessed on 2 October 2014).

- US Environmental Protection Agency. Drinking Water Contaminants. Available online: http://water.epa.gov/drink/contaminants/ (accessed on 2 October 2014).

- SSA. Salud ambiental. Agua para Uso y Consumo Humano-Límites Permisibles de Calidad y Tratamiento a que debe Someterse el Agua para su Potabilización. Modificación a la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-127-SSA1-1994. Available online: http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/m127ssa14.html (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-231-SSA1-2002. Available online: http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/231ssa102.pdfl (accessed on 10 October 2014).

- Guidance Documents & Regulatory Information by Topic—Lead in Candy Likely To Be Consumed by Small Children. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/ucm077904.htm (accessed on 2 October 2014).

- Horton, M. California Department of Public Health Warns Consumers not to Eat Huevines Confitados Sabor Chocolate Candy Imported from Mexico; News Release PH08-39; California Department of Public Health: Canifornia, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez-Lugo, M.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M.; Gómez-Dantés, H.; Hernández-Avila, M. Trends in atmospheric concentrations of lead in the metropolitan area of Mexico city, 1988–1998. Salud Pública México 2003, 45, S196–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.E.; Pérez, M.C.; Ericson, B.; Gualtero, S.; Smith-Jones, A.; Caravanos, J. Childhood blood lead reductions following removal of leaded ceramic glazes in artisanal pottery production: A success story. Blacksm. Inst. J. Health Pollut. 2013, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias-Pérez, M.; Estrada-Sánchez, D.; Luft-Dávalos, R.; Ruiz-Romero, E.; Berrocal-López, E.; Jones, D.E.; Fuller, R.; Ericson, B.; Becker, D. Uso de Plomo en la Alfarería en México; Informe 2010; FONART, Blacksmith Institute: Kabwe, Zambia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- FONART. Programa Nacional para la Adopción del Esmalte Libre de Plomo; Informe 2009–2011; Fondo Nacional para el Fomento de las Artesanías: San Pedro, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, E. Childhood lead poisoning: Conservative estimates of the social and economic benefits of lead hazard control. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichery, C.; Bellanger, M.; Zmirou-Navier, D.; Glorennec, P.; Hartemann, P.; Grandjean, P. Childhood lead exposure in France: Benefit estimation and partial cost-benefit analysis of lead hazard control. Environ. Health Glob. Access Sci. Source 2011, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farías, P.; Álamo-Hernández, U.; Mancilla-Sánchez, L.; Texcalac-Sangrador, J.L.; Carrizales-Yáez, L.; Riojas-Rodríguez, H. Lead in School Children from Morelos, Mexico: Levels, Sources and Feasible Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12668-12682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212668

Farías P, Álamo-Hernández U, Mancilla-Sánchez L, Texcalac-Sangrador JL, Carrizales-Yáez L, Riojas-Rodríguez H. Lead in School Children from Morelos, Mexico: Levels, Sources and Feasible Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014; 11(12):12668-12682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212668

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarías, Paulina, Urinda Álamo-Hernández, Leonardo Mancilla-Sánchez, José Luis Texcalac-Sangrador, Leticia Carrizales-Yáez, and Horacio Riojas-Rodríguez. 2014. "Lead in School Children from Morelos, Mexico: Levels, Sources and Feasible Interventions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11, no. 12: 12668-12682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212668

APA StyleFarías, P., Álamo-Hernández, U., Mancilla-Sánchez, L., Texcalac-Sangrador, J. L., Carrizales-Yáez, L., & Riojas-Rodríguez, H. (2014). Lead in School Children from Morelos, Mexico: Levels, Sources and Feasible Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(12), 12668-12682. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111212668