Older Clients’ Pathway through the Adaptation System for Independent Living in the UK

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

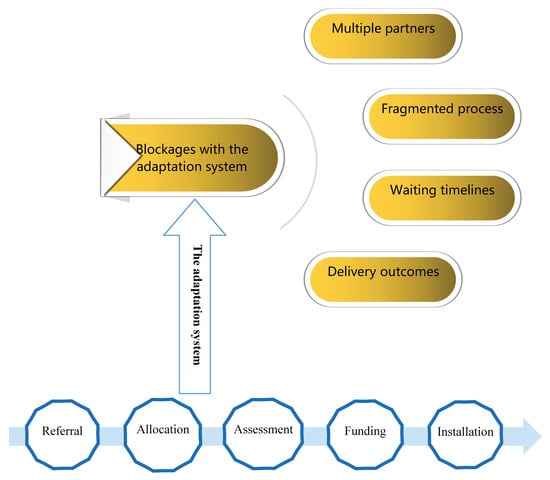

3.1. Multiple Partners

“We are independent and flexible to provide services through the whole process from referral to completion. For example, the grant application needs the title deed, the approval of building insurance, the approval of all the client’s incomes, and the letter from the mortgage provider if the client still has mortgage; older people have no idea how to prepare them. We can go to the client’s house with a big pile of paperwork and help them to go through what it is looking for.”

“We can spend time with clients and help them through the whole process. This is really care, not just repair. Care is a very important part, because getting adaptations done can be very stressful for older people. This is why most C&R are quite successful.”

“At the beginning I had some worries about the shower and the toilet seat, which come out around thousands of pounds and need certain building work. Care and Repair got everything done for me. Brilliant!”

“As the exact procedures and resources for adaptations are decided by the council, we are not able to use innovative ideas to improve the process or save the budget. We can just do what we have been told.”

“The enquiry and assessment processes are managed by the county’s occupational therapy staff, the local authority has no involvement in this other than signposting.”

“Having one dedicated team based in one location would be beneficial to reduce waiting times and streamline the process.”

“Better alignment of IT system enables all partners to transfer information and to monitor cases effectively.”

“No, we don’t have a shared system and we suppose we should have more information. We don’t have any access to the council system, we have our own system. So it just wasn’t practical.”

“Because there isn’t a single shared system, we don’t know how long the process takes and which stage the case is at. We can only advise to the council if we have any problems on our own.”

3.2. Fragmented Process

“People are often unclear who they need to approach when they require an adaptation, so the route to referral can vary–they approach their housing provider, they visit their General Practice (GP) doctor, they are referred by a health professional whilst in hospital, they are referred by hospital occupational therapist, they contact their local authority, they contact their social worker, or they ask a relative or carer.”

“If I have a problem, I will first contact my doctor, they can get referrals through consultants. My doctor will speak to consultants in hospitals and they will then put me in touch with specialists in the council.”

“Any enquiries made directly to our council are usually referred to social services on the same day when a standard form provided by social services.”

“Our staff and seniors on a regular basis screen the initial enquiries and then decide what priority they fit into.”

“A priority scoring system gives us the opportunity to deal with the most complicated situations and to visit high priority cases more quickly.”

“There are lengthy waiting lists to be assessed by occupational therapists especially if the adaptation isn’t seen as critical by the local authority.”

“The available budget is only sufficient to resource critical and substantial cases living in private sector housing.”

“Based on the client’s needs each case is prioritized and given a number of points 6, 7 up to 13. Most clients are 11 or 12 points. So for those with 8, 9 or 10 points, there is really no chance for them.”

“We provide adaptations to people in priority 3 or 4 (low level category priority). The reason we do that is prevention. We provide these people with adaptations, so that they can manage to get downstairs, hopefully, without falls. For a long time, this will save lots of money and improve quality of life for these people, meaning they are more likely to keep active, not get worse, and not have accidents.”

“When we tell older clients that we need these documents, in most cases, they are scared and don’t know what they are going to get. So the process would be a lot slower.”

“Delays mainly result from obtaining landlord permission for private rented tenants and social tenants.”

“We have had some occasions, where the landlord would not allow the adaptation to go ahead, so the tenant had to find another place. That’s a shame.”

“Sometimes the landlord would rather ask an elderly person to move than adapt a family home for him or her.”

“There should be the option and some money to put the home back when a tenant no longer requires the adaptation, but I have never heard of it. This doesn’t happen in our council, and most of councils won’t put money in this area.”

“Where we have a direct involvement, we arrange to meet the OT and the contractor on site to discuss the specification of the installation.”

“The OT, the technical officer and the grant officer will visit the site together to decide the specifications of the adaptation.”

“We have a list of trusted contractors and have built good relationships with them over ten years.”

“C&R suggested the names of a few contractors on their list and got quotes from them. They provided me with the three least expensive ones because of my funding, then I picked.”

“Every adaptation met our expectations and most of clients were happy with the contractor’s work.”

“To minimize waiting times for adaptation, we need more technical staff to assist clients with their enquiries and more suitable building contractors.”

3.3. Waiting Timelines

“Demand for adaptations exceeds financial resources, which means a waiting list for DFGs.”(a housing officer).

“Delays can often occur when clients are required to find the necessary resources towards a funding contribution or share of the costs.”

“If that is the case that the clients only get 80% of the cost, we have to try to raise the money through other ways. Because the clients have a low income, they probably would not have access.”

“These legal requirements need to follow; I can understand that. It is just annoying that they add a number of weeks to the process.”

“When somebody has been offered the grant, by law, they have up to one year to spend that and don’t have to start the works straight away.”

“DFGs are valid for 12 months following approval. Cases that exceed this period are reviewed on a case by case basis and will only be extended if there are reasonable causes.”(a housing officer).

“Applicants have an initial 12 months to use their grant award. If it is not spent within that period, the council will discuss options with the client to extend the time period and to assist them in taking the project forward.”(a housing officer).

“There are huge variations in the number of occupational therapists per population in each area. The waiting lists for assessment vary considerably.”

“We use self-assessment models for low level adaptations to allow greater capacity for OT staff to deal with cases in a reduced time frame.”

“The use of OT assistants for less complex case is effective to alleviate delays in getting assessments.”

“We train staff from housing, social work and NHS who can carry out assessments for simple requests, while professional assessments are undertaken by OTs for people who have more complex needs. This is effective in controlling the waiting lists.”

“We often get poor information. A worst case scenario is, a GP sees an older person and would say, Miss XX is really struggling and needs an OT assessment. But we don’t know how urgent the case is and we don’t know in which way the person is struggling with, so she is put in the waiting list.”

3.4. Delivery Outcomes

“More and more older people demand adaptations, which always outstrips supply in our council.”

“Compared with the number of completed adaptations, the demand is far higher, because the population is aging.”

“We had the same money in total since 2007, the funding has not gone up. In fact, it has gone down. Technically, it has gone down, because the living expense has gone up.”

“The number of adaptations required are increasing year on year. The demand exceeds financial resources.”

“Most people waiting for adaptations are first asked to self-referral through an online system. This saves our staff lots of time and helps people to enter the service quickly.”

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, J.M. Health status and health services utilization in elderly Koreans. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slaug, B.; Schilling, O.; Iwarsson, S.; Carlsson, G. Defining profiles of functional limitations in groups of older persons: How and why? JAH 2011, 23, 578–604. [Google Scholar]

- Tinker, A. The social implications of an ageing population. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2002, 123, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, P.B.; Mayer, K.U. The Berlin Aging Study: Aging from 70 to 100; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, F.; Oldman, J.; Means, R. Housing and Home in Later Life; McGraw Hill Education: Buckingham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R. The Built Environment and Public Health; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abramsson, M.; Andersson, E. Changing preferences with ageing–housing choices and housing plans of older people. Hous. Theory Soc. 2016, 33, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, K.M.; Sadana, R. On the ethics of healthy ageing: Setting impermissible trade-offs relating to the health and well-being of older adults on the path to universal health coverage. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, R.J. The impact of the built environment on health: An emerging field. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1382–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, K. Ageing in Place: Coordinating Housing and Healthcare Provision for Americas Growing Elderly Population; Joint Centre for Housing Studies of Harvard University: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Renaut, S.; Ogg, J.; Petite, S.; Chamahian, A. Home environments and adaptations in the context of ageing. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 1278–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson, S.; Ståhl, A. Accessibility, usability and universal design—positioning and definition of concepts describing person-environment relationships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, F.; Wahl, H.W.; Schilling, O.; Nygren, C.; Fänge, A.; Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J.; Szeman, Z.; Tomsone, S.; Iwarsson, S. Relationships between housing and healthy aging in very old age. Gerontologist 2007, 47, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bull, R.; Watts, V. The legislative and policy context. In Housing Options for Disabled People; Bull, R., Ed.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jette, A.M. Toward a common language for function, disability, and health. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbarah, M.; Silverstein, M.; Seeman, T. A health and demographic profile of noninstitutionalized older Americans residing in environments with home modifications. JAH 2000, 12, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N. Testing home modification interventions: Issues of theory. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1998, 18, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P. The relative impact of congregate and traditional housing on elderlytenants. Gerontologist 1976, 16, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, T.; Stephens, C. Constructing housing decisions in later life: A discursive analysis of older adults’ discussions about their housing decisions in New Zealand. Hous. Theory Soc. 2017, 34, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, J. The meaning of home: An exploratory study of environmental experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 1986, 6, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, F.; Schilling, O.; Wahl, H.W.; Gäng, K. Trouble in paradise? Reasons to relocate and objective environmental changes among well-off older adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.W.; Weisman, G.D. Environmental gerontology at the beginning of the new millennium: Reflections on its historical, empirical, and theoretical development. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutchin, M.P. The process of mediated aging-in-place: A theoretically and empirically based model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G.D. Place and personal identity in old age: Observations from appalachia. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahemow, L.; Lawton, M.P. Toward an ecological theory of adaptation and aging. Environ. Des. Res. 1973, 1, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fänge, A.; Iwarsson, S. Accessibility and usability in housing: Construct validity and implications for research and practice. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitlin, L.N. Conducting research on home environments: Lessons learned and new directions. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wahl, H.W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, L.L.; Steggell, C.D.; Iwarsson, S. Adaptive strategies and person-environment fit among functionally limited older adults aging in place: A mixed methods approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2005, 12, 11954–11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P. Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people. In Aging and the Environment: Theoretical Approaches; Lawton, M.P., Windley, P.G., Byerts, T.O., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Volume 7, pp. 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.W. Environmental influences on aging. Handb. Psychol. Aging. 2001, 3, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Fänge, A.; Iwarsson, S. Changes in ADL dependence and aspects of usability following housing adaptation—A longitudinal perspective. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 59, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thordardottir, B.; Chiatti, C.; Ekstam, L.; Malmgren Fänge, A. Heterogeneity of Characteristics among Housing Adaptation Clients in Sweden—Relationship to Participation and Self-Rated Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettersson, C.; Löfqvist, C.; Malmgren Fänge, A. Clients’ experiences of housing adaptations: A longitudinal mixed-methods study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1706–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, W.S.; Oyegoke, A.S.; Sun, M. Service planning and delivery outcomes of home adaptations for ageing in the UK. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carnemolla, P.; Bridge, C. Housing Design and Community Care: How Home Modifications Reduce Care Needs of Older People and People with Disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 1616, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gitlin, L.N.; Winter, L.; Dennis, M.P.; Corcoran, M.; Schinfeld, S.; Hauck, W.W. A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heywood, F. Adaptation: Altering the house to restore the home. Hous. Stud. 2005, 20, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care and Repair Cymru. Rapid Response Adaptations Programme Strategic and Operations Customer Satisfaction Survey Report; C&R Cymru: Cardiff, Wales, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, F.; Turner, L. Better Outcomes, Lower Costs. Implications for Health and Social Care Budgets of Investment in Housing Adaptations, Improvements and Equipment: Review of the Evidence; Department of Work and Pensions: London, UK, 2007.

- Kim, H.; Ahn, Y.H.; Steinhoff, A.; Lee, K.H. Home modification by older adults and their informal caregivers. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibbings, J.; Boniface, G.; Campbell, J.; Findlay, G.; Reeves-McAll, E.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, P. A Review of Independent Living Adaptations; Welsh Government: Cardiff, Wales, 2015.

- Jones, C. Review of Housing Adaptations Including Disabled Facilities Grants–Wales; Welsh Government: Cardiff, Wales, 2005.

- Zhou, W.S.; Oyegoke, A.S.; Sun, M. Causes of Delays during Housing Adaptation for Healthy Aging in the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Home Adaptations Consortium. Home Adaptations for Disabled People: A Detailed Guide to Related Legislation, Guidance and Good Practice; Care & Repair England: Nottingham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, F. Adaptations–Finding Ways to Say Yes; SAUS: Bristol, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.S.; Oyegoke, A.S.; Sun, M. Adaptations for Aging at Home in the UK: An Evaluation of Current Practice. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Which Partners are Working Together for the Delivery of Adaptations in Local Council? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Department | The Integration Authority | Social Work | Associated Organizations | Others | |

| n | 93 | 15 | 83 | 75 | 26 |

| % | 83.0% | 13.4% | 74.1% | 67.0% | 23.2% |

| Are there written guidance specified service entitlements and service processes between the partners? | |||||

| Yes | No | ||||

| n | 87 | 23 | |||

| % | 79.1% | 20.9% | |||

| How is the effectiveness of current joint work? | |||||

| Very ineffective | Fairly ineffective | Fairly effective | Very effective | ||

| n | 5 | 4 | 57 | 42 | |

| % | 4.6% | 3.7% | 52.8% | 38.9% | |

| Number of Local Authorities Received Different Levels of Self-Referrals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Adaptations | None (n = 43) | 1–25% (n = 26) | 26–50% (n = 5) | 51–75% (n = 9) | Over 75% (n = 9) |

| Fewer than 50 | 23.3% | 15.4% | 0.0% | 33.3% | 0.0% |

| 50–100 | 41.9% | 30.8% | 0.0% | 44.5% | 11.1% |

| 101–150 | 20.9% | 19.2% | 0.0% | 11.1% | 33.3% |

| 151–200 | 9.3% | 3.8% | 40.0% | 11.1% | 33.3% |

| Over 200 | 4.6% | 30.8% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 22.3% |

| The Use of an Initial Screening Mechanism | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of Adaptations | Yes (n = 73) | No (n = 20) |

| Fewer than 50 | 15.1% | 30.0% |

| 51–100 | 28.8% | 45.0% |

| 101–150 | 17.8% | 25.0% |

| 151–200 | 16.4% | 0.0% |

| Over 200 | 21.9% | 0.0% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, W.; Oyegoke, A.S.; Sun, M.; Zhu, H. Older Clients’ Pathway through the Adaptation System for Independent Living in the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103640

Zhou W, Oyegoke AS, Sun M, Zhu H. Older Clients’ Pathway through the Adaptation System for Independent Living in the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(10):3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103640

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Wusi, Adekunle Sabitu Oyegoke, Ming Sun, and Hailong Zhu. 2020. "Older Clients’ Pathway through the Adaptation System for Independent Living in the UK" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 10: 3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103640

APA StyleZhou, W., Oyegoke, A. S., Sun, M., & Zhu, H. (2020). Older Clients’ Pathway through the Adaptation System for Independent Living in the UK. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103640