Budgeting for Environmental Health Services in Healthcare Facilities: A Ten-Step Model for Planning and Costing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Costing-Stakeholders

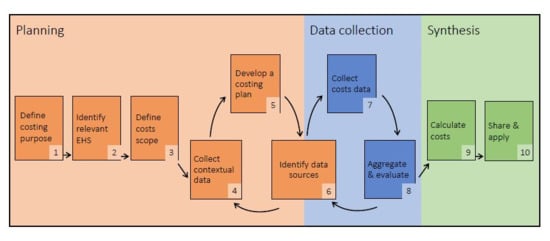

3.2. Model Overview

3.3. Step 1: Define Costing Purpose

3.3.1. Time and Resources Required for Budgeting

3.3.2. Defining Target Outcomes, Target Facilities, and Timeframes

3.4. Step 2: Identify Relevant EHS

3.4.1. Defining EHS in HCFs

3.4.2. Defining EHS Modalities and Levels

3.5. Step 3: Define the Scope of Relevant Costs

3.6. Step 4: Collect Non-Cost Contextual Data

3.7. Step 5: Develop a Costing Plan

3.7.1. Selecting Cost Data Collection Sites

3.7.2. Costing Frameworks

3.7.3. Costing Approaches

3.8. Step 6: Identify Data Sources

3.9. Step 7: Collect Cost Data

3.10. Step 8: Aggregate and Evaluate

3.11. Step 9: Calculate Costs

Unit Costs

3.12. Step 10. Share and Apply

3.13. Application of this Model Toward Future Research

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouzid, M.; Cumming, O.; Hunter, P.R. What is the impact of water sanitation and hygiene in healthcare facilities on care seeking behaviour and patient satisfaction? A systematic review of the evidence from low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittet, D.; Allegranzi, B.; Storr, J.; Donaldson, L. Clean Care is Safer Care: The Global Patient Safety Challenge 2005–2006. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 10, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ducel, G.; Fabry, J.; Nicolle, L. Prevention of Hospital-Acquired Infections, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allegranzi, B.; Nejad, B.S.; Combescure, C.; Graafmans, W.; Attar, H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, S.B.; Allegranzi, B.; Syed, S.B.; Ellis, B.; Pittet, D. Health-care-associated infection in Africa: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. National and State Healthcare Associated Infections: Progress Report; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016.

- Weinstein, R.A. Epidemiology and control of nosocomial infections in adult intensive care units. Am. J. Med. 1991, 91, S179–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Bartram, J.; Chartier, Y. Essential Environmental Health Standards in Health Care Geneva; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. General Assembly: Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sutstainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WASH in Health Care Facilities: Global Baseline Report 2019; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Core Questions and Indicators for Monitoring WASH in Healthcare Facilities in the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://washdata.org/monitoring/health-care-facilities (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Cronk, R.; Bartram, J. Environmental conditions in health care facilities in low and middle-income countries: Coverage and inequalities. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS) 2017 Report: Financing Universal Water, Sanitation and Hygiene under the Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- D’Mello-Guyett, L.; Cumming, O. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Health Care Facilities: Global Strategy, Burden of Disease, and Evidence and Action Priorities; WHO: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.; Cronk, R.; Fejfar, D.; Pak, E.; Cawley, M.; Bartram, J. Safe healthcare facilities: A systematic review on the costs of establishing and maintaining environmental health in facilities in low-and middle-income countries in submission. J. Cleaner Pro. 2020. submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Schwelltzer, R.W.; Grayson, C.; Lockwood, H. WASHCost Tool; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Snehalatha, M.; Fonsesca, C.; Rahman, M.; Uddin, R.; Ahmed, M.; Sharif, A.J. School WASH Programmes in Bangladesh: How Much Does It Cost? Applying the Life-Cycle Costs Approach in Selected Upazilas; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, M.F.; Sculpher, M.J.; Claxton, K.; Stoddart, G.L.; Torrance, G.W. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, C.E. Health Economics; Routledge: Abingdon upon Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Radin, M.; Jeuland, M.; Wang, H.; Whittington, D. Benefit-Cost Analysis of Community-Led Total Sanitation: Incorporating Results from Recent Evaluations, 2019. HARVARD H.C. CHAN School of Public Health Website. Available online: https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2017/01/Radin-Jeuland-Whittington-CLTS-2019.01.07.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Wong, B.; Radin, M. Benefit-Cost Analysis of a Package of Early Childhood Interventions to Improve Nutrition in Haiti. J. Benefit Cost Anal. 2019, 10, 154–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whittington, D.; Radin, M.; Jeuland, M. Evidence-based policy analysis? The strange case of the randomized controlled trials of community-led total sanitation. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36, 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, J.; Saywell, D.; Shields, K.F.; Kolsky, P.; Bartram, J. The true costs of participatory sanitation: Evidence from community-led total sanitation studies in Ghana and Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Management of Wastes from Health Care Activities. Available online: https://www.who.int/docstore/water_sanitation_health/wastemanag/ch13.htm (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Environmental Infection Prevention in Health-Care Facilities; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2003.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Core Competencies for Infection Control and Hospital Hygiene Professionals in the European Union Stockholm; ECDC: Solna, Sweden, 2013.

- Alexander, K.T.; Mwaki, A.; Adhiambo, D.; Cheney-Coker, M.; Muga, R.; Freeman, M.C. The life-cycle costs of school water, sanitation and hygiene access in Kenyan primary schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGinnis, S.M.; McKeon, T.; Desai, R.; Ejelonu, A.; Laskowski, S.; Murphy, H.M. A Systematic Review: Costing and Financing of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) in Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drummond, M.F.; Stoddart, G.L. Economic analysis and clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1984, 5, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Petrou, S.; Carswell, C.; Moher, D.; Greenberg, D.; Augustovski, F.; Briggs, A.H.; Mauskopf, J.; Loder, E. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2013, 346, f1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drummond, M.F.; Jefferson, T.O. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the British Medical Journal. Br. Med. J. 1996, 313, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchaivijitr, S.; Tangtrakool, T.; Chokloikaew, S.; Thamlikitkul, V. Universal precautions: Costs for protective equipment. Am. J. Infect. Control 1997, 25, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.L. Applying Quality Management in Healthcare: A Systems Approach; Health Administration Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, J. Product Lifecycle Management. In Product Lifecycle Management: 21st Century Paradigm for Product Realisation; Stark, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 21, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, M.A.; Bartram, J.; Elimelech, M. Increasing Functional Sustainability of Water and Sanitation Supplies in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2009, 26, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoa, V.T.H.; Van Trang, D.T.; Tien, N.P.; Van, D.T.; Wertheim, H.F.; Son, N.T. Cost-effectiveness of a hand hygiene program on health care-associated infections in intensive care patients at a tertiary care hospital in Vietnam. Am. J. Infect. Control 2015, 43, e93–e99. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji, S.; MacIntyre, C.R.; Seale, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, P.; Wang, X.; Newall, A.T. Cost-effectiveness analysis of N95 respirators and medical masks to protect healthcare workers in China from respiratory infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adhikari, S.R.; Supakankunit, S. Benefits and costs of alternative healthcare waste management: An example of the largest hospital of Nepal. WHO South East Asia J. Public Health 2014, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boardman, A.E.; Greenberg, D.H.; Vining, A.R.; Weimer, D.L. Cost-Benefit Analysis: Concepts and Practice, 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, T.; Murray, C. Making Choices in Health: WHO Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, Y. Safe Management of Wastes from Health-Care Activities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF. Expert Group Meeting on Monitoring WASH in Health Care Facilities in the Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Standard Precautions in Healthcare; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reuland, F.; Behnke, N.; Cronk, R.; McCord, R.; Fisher, M.; Abebe, L.; Suhlrie, L.; Joca, L.; Mofolo, I.; Kafanikhale, H.; et al. Energy access in Malawian healthcare facilities: Consequences for health service delivery and environmental health conditions. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 35, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, D.G. Life cycle costing—Theory, information acquisition and application. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1997, 15, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, B.S. Life Cycle Costing for Engineers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alagöz, A.Z.; Kocasoy, G. Improvement and modification of the routing system for the health-care waste collection and transportation in İstanbul. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.J.; Kapalamula, J.; Chisimbi, S. The cost of the district hospital: A case study in Malawi. Bull. World Health Organ. 1993, 71, 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, B.C.; Seetharam, A.M.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Kamath, R. Comparative analysis of cost of biomedical waste management across varying bed strengths in rural India. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2018, 11, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, D.; Eitzinger, S. Pitfall benchmarking of cleaning costs in hospitals. J. Facil. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHS Program. Service Provision Assessment. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/SPA.cfm (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): An Annual Monitoring System for Service Delivery. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/sara_indicators_questionnaire/en/ (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Scheaffer, R.L.; Mendenhall, I.I.I.W.; Ott, R.L.; Gerow, K.G. Elementary Survey Sampling, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr, S.L. Sampling: Design and Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abeygunasekera, A.M.; Duminda, M.T.; Chamintha, T.; Jayasingha, R. The operational cost of a urology unit. Ceylon Med. J. 2008, 53, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alagöz, B.A.Z.; Kocasoy, G. Treatment and disposal alternatives for health-care waste in developing countries—A case study in Istanbul, Turkey. Waste Manag. Res. 2007, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabbadi, I.; Mahafza, A.; Al-Abbadi, M.A.; Bakir, A. Investment Opportunities in Health: Feasibility of Building an American Private Hospital in Jordan. Editor. Advis. Board 2013, 40, 312–329. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, R.N. Issues involved in hospital waste management—An experience from a large teaching institution. J. Acad. Hosp. Adm. 1995, 7, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Caniato, M.; Tudor, T.L.; Vaccari, M. Assessment of health-care waste management in a humanitarian crisis: A case study of the Gaza Strip. Waste Manag. 2016, 58, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khammaneechan, P.; Okanurak, K.; Sithisarankul, P.; Tantrakarnapa, K.; Norramit, P. Effects of an incinerator project on a healthcare-waste management system. Waste Manag. Res. 2011, 29 (Suppl. 10), 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Jithesh, V.; Gupta, S.K. Does a single specialty intensive care unit make better business sense than a multi-specialty intensive care unit? A costing study in a trauma center in India. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2015, 9, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Filho, D.B.; Ximenes, R.A.; Siqueira-Filha, N.T.; Santos, A.C. Incremental costs of treating tetanus with intrathecal antitetanus immunoglobulin. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2013, 18, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Perera, Y.S.; Makarim, M.F.M.; Wijesinghe, A.; Wanigasuriya, K. The costs in provision of haemodialysis in a developing country: A multi-centered study. BMC Nephrol. 2011, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rao, S.; Ranyal, R.K.; Bhatia, S.S.; Sharma, V.R. Biomedical Waste Management: An Infrastructural Survey of Hospitals. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2004, 60, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rashidian, A.; Alinia, C.; Majdzadeh, R. Cost-effectiveness analysis of health care waste treatment facilities in iran hospitals; A provider perspective. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Gupta, S.; Daga, A.; Siddharth, V.; Wundavalli, L. Cost analysis of a disaster facility at an apex tertiary care trauma center of India. J. Emergencies Trauma Shock 2016, 9, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.R.; Finotti, A.R.; da Silva, V.P.; Alvarenga, R.A. Applications of life cycle assessment and cost analysis in health care waste management. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Compendium of technologies for treatment/destruction of healthcare waste. In UNEP DTIE International Environmental Technology Centre (IETC); UNEP: Osaka, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chapko, M.K.; Liu, C.F.; Perkins, M.; Li, Y.F.; Fortney, J.C.; Maciejewski, M.L. Equivalence of two healthcare costing methods: Bottom-up and top-down. Health Econ. 2009, 18, 1188–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batura, N.; Pulkki-Brännström, A.-M.; Agrawal, P.; Bagra, A.; Haghparast-Bidgoli, H.; Bozzani, F.; Colbourn, T.; Greco, G.; Hossain, T.; Sinha, R.; et al. Collecting and analysing cost data for complex public health trials: Reflections on practice. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 23257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tianviwat, S.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Birch, S. Estimating unit costs for dental service delivery in institutional and community-based settings in southern Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2009, 21, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, S.A.; Qadiri, G.J.; Hassan, G. Cost analysis of central sterlisation services at a tertiary care medical institute. J. Acad. Hosp. Adm. 1994, 6, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, G.; Chase, C. The Knowledge Base for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal Targets on Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paulus, A.; van Raak, A.; Keijzer, F. Core Articles: ABC: The Pathway to Comparison of the Costs of Integrated Care. Public Money Manag. 2002, 22, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, M.; Smith, T.H. Evaluation of activity-based costing versus resource-based relative value costing. J. Med. Pract. Manag. MPM 2004, 19, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Negrini, D. The cost of a hospital ward in Europe: Is there a methodology available to accurately measure the costs? J. Health Organ. Manag. 2004, 18, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.D.; Balas, A.; West, D.A. Contrasting RCC, RVU, and ABC for managed care decisions. Healthc. Financ. Manag. 1996, 50, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, M.E.; Kundu, P.; Boers, A.C.; Bolarinwa, O.A.; Te Pas, M.J.; Akande, T.M.; Agbede, K.; Gomez, G.B.; Redekop, W.K.; Schultsz, C.; et al. Step-by-step guideline for disease-specific costing studies in low-and middle-income countries: A mixed methodology. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 23573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shim, J.K.; Siegel, J.G.; Shim, A.I. Budgeting Basics and Beyond, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koontz, H. Essentials of Management; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: Pennsylvania Plaza, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stackpole, C.S. A User’s Manual to the PMBOK Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen, J.T.; Lereim, J. Management of Project Contingency and Allowance: A Publication of the American Association of Cost Engineers a Publication of the American Association of Cost Engineers. Cost Eng. 2005, 47, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Layard, P.R.G. Cost-Benefit Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, T.; Bozzani, F.; Vassall, A.; Remme, M.; Sinanovic, E. Comparing the Application of CEA and BCA to Tuberculosis Control Interventions in South Africa. J. Benefit Cost Anal. 2019, 10, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anbari, F.T. Earned Value Project Management Method and Extensions. Proj. Manag. J. 2003, 34, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, M. Crowdsourced health research studies: An important emerging complement to clinical trials in the public health research ecosystem. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. UN Water: National Systems to Support Drinking-Water: Sanitation and Hygiene: Global Status Report 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Costing Step | Actions | |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | 1. Define costing purpose | Determine the time and resources available for costing Consult stakeholders to agree a costing purpose and application of data Identify outcomes targeted by spending (e.g., reduce healthcare-acquired infections, meet Joint Monitoring Program (JMP) basic sanitation guidelines) Identify a location, target facilities, and a timeframe for target outcomes |

| 2. Identify relevant EHS | Identify which EHS will be the focus of costing activities Determine relevant modality/ies of EHS provision (e.g., waste management through incineration) Determine relevant EHS provision level(s) (e.g., JMP basic-level waste management) | |

| 3. Define the scope of relevant costs | Define the scope of relevant costs. Consider both technology lifecycles and cost categories. Justify any exclusions of scope as per costing purpose | |

| 4. Collect non-cost contextual data | Describe facility characteristics (e.g., size, patient volume, services provided) Evaluate EHS quantity and quality, and identify any differences between actual and aspirational EHS quantity and quality Assess how EHS are provided. Document EHS inputs and outputs | |

| 5. Develop a costing plan | Develop a costing framework that identifies expected expenses based on EHS inputs and outputs identified in step 4 Select cost data collection sites † Develop a costing plan that identifies the approach (e.g., top-down, bottom-up, hybrid) and data collection tools Secure relevant ethical and administrative permission Pilot test tools at selected data collection sites. Revise as necessary | |

| 6. Identify data sources | Identify key informants and records systems for data collection. Informants may be internal to the facility or external (e.g., contractors or construction firms) Assess the feasibility of the costing plan from Step 4 based on available data sources. Revise as necessary. | |

| Data collection | 7. Collect cost data | Execute the costing plan from Step 5. Collect data from all relevant data sources identified in step 6 Document each data source and iteration (see step 8) Ask relevant stakeholders to evaluate data quality and completeness for each source |

| 8. Aggregate and evaluate | Aggregate data from all sources and categorize into the costing framework Compare expected versus documented costs and identify data gaps Iterate steps 6–8 to fill these gaps | |

| Synthesis | 9. Calculate costs | Calculate total costs. Adjust for taxes, subsidies/tariffs, financing costs, deprecation, or other factors as needed Calculate relevant unit costs Conduct sensitivity analysis (e.g., identify potential variance in costs, inflation) |

| 10. Share and apply | Adhere to reporting guidelines for economic studies‡ Share and review with internal stakeholders as a final validity check Disseminate more widely to external stakeholders. Make data publicly available when possible. Plan for updating information systems, recurrent data collection, learning |

| Example 1: Operating and Maintaining Existing Services | Example 2: Rehabilitating Inadequate Services | Example 3: Installing New Services | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | District hospital establishing an annual operations and maintenance budget for waste management | Government of Cambodia budgeting for facility upgrades in fiscal year 2021/2022 | Non-governmental organization constructing improvements in a small network of private facilities |

| Define costing purpose | Target facility and outcome: Safely operate and maintain waste disposal equipment in a district hospital in urban Maputo for one year | Target facility and outcome: Rehabilitate sanitation facilities to meet WHO guidelines for menstrual hygiene management and disabilities access for all health posts in three rural provinces of Cambodia | Target facility and outcome: Provide access to basic water for drinking and care provision for 10 years at five clinics in rural Zambia currently relying on surface water and intermittent rainwater harvesting |

| Identify relevant EHS | Relevant EHS: Waste management Modality: Incinerator, waste pits Service level: Compliance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for safe management of infectious and sharps waste 1 | Relevant EHS: On-site sanitation Modality: Pit latrines Service level: Improved facilities meeting WHO guidelines for menstrual hygiene management and disability accessibility 2 | Relevant EHS: On-site water source Modality: Boreholes with solar pump, to be connected to existing rooftop rainwater harvesting containers and gravity-fed distribution system Service level: JMP basic water |

| Define the scope of relevant costs | Lifecycle: Operations and maintenance for 1 year Cost categories: Capital maintenance, consumables, personnel, and direct support Excluded from scope: Capital hardware, capital software, and financing costs excluded because infrastructure is already established | Lifecycle: Installation of new or upgraded latrines; disposal or demolition of existing latrines Cost categories: Capital hardware, capital software, financing Excluded from scope: Capital maintenance, consumables, recurrent training, personnel, and direct support, as operations and maintenance covered under separate financing stream | Lifecycle: Installation, operation, and maintenance for 10 years Cost categories: Capital hardware, capital maintenance Excluded from scope: Capital software and recurrent training as boreholes are common locally and staff already know how to use them; consumables as guidelines for basic service do not require testing |

| Collect non-costs contextual data | Assess Joint Monitoring Program (JMP) indicators for waste management and compliance with WHO guidelines in step 1. Qualitatively document waste disposal equipment, common maintenance requests, consumables, and staff training for operation of equipment | Design a random sample of health post, stratified by province. Assess JMP indicators for sanitation and WHO indicators for disability and menstrual hygiene accessibility. Assess rehabilitation needs, and identify major repair types | Document existing water infrastructure in target clinics. Assess demand for water based on patient volume and type of service provided |

| Develop a costing plan | Costing framework: Categorize inputs identified in step 4 into facility-specific framework Cost data collection sites: Target facility Approach: Hybrid top-down and bottom-up costing Data collection tools: Identify key informants, utilize existing budgets and records from maintenance department, develop surveys to assess consumable and personnel costs | Costing framework: Develop frameworks for expected expenses for each major repair type Cost data collection sites: Purposively sample 2 and 3 facilities to match major repair type for costing Approach: Bottom-up Data collection tools: Develop surveys to assess resource inputs and unit costs to rehabilitate latrines | Costing framework: Identify expected expenses based on local borehole installation practices Cost data collection sites: Select facilities with basic services comparable to target clinics Approach: Top-down costing Data collection tools: Past budgets or contract bids for borehole installation; codebooks to identify and apportion relevant expenses |

| Identify data sources | Verify existence of budgets for maintenance for top-down costing Pilot test surveys for bottom-up costing | Identify maintenance and construction workers knowledgeable about rehabilitation costs. Supplement with external contractors as needed | Verify that records exist to facilitate top-down costing |

| Sample iteration in planning phase | Data sources for top-down costing are unavailable (no budgets records kept). Account for equipment and parts needed for maintenance through bottom-up costing. Verify through contacting external maintenance contractors | Facilities selected during purposive sampling do not match repair types. Resample to identify appropriate facilities | Data sources for top-down costing are unavailable (no records kept) at data collection sites. Contact local contractors for estimates of borehole installation |

| Cost Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Capital hardware | Infrastructure or equipment purchases required to establish services or implement changes to EHS delivery method, which are not consumed during normal EHS operation |

| Capital maintenance | Expenses required to repair, rehabilitate, or otherwise maintain functionality of capital hardware, including labor costs required for these purposes |

| Capital software | Planning, procurement, and initial training costs associated with establishing new services or implementing changes to EHS delivery method |

| Recurrent training | Training required to ensure proper ongoing EHS provision, regardless of changes to EHS delivery |

| Consumables | Products and supplies that are consumed during normal operation |

| Personnel | Labor costs associated with normal operation of a service, including staff benefits |

| Direct support | Expenses required to supervise and monitor EHS provision to ensure safety and sustainability that support, but do not have direct EHS outputs, such as auditing or developing management plans |

| Financing | Loan interest and other fees associated with EHS financing |

| Contracted services | Fees paid to external providers to perform all or part of normal EHS operation, including multiple other cost categories, where expenses cannot be accurately disaggregated into categories above; where fees fall solely within another cost category described above, expenses should be included therein |

| Activity | Expense Category † | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Hardware | Capital Maintenance | Capital Software | Recurrent Training | Consumables | Personnel | Direct Support | Financing | Contracted Services | |

| Collection, segregation, packaging, and storage | Point-of-use waste receptacles; interim bulk storage containers; syringe/needle cutters; storage room/area; storage area refrigeration units; waste weighing scale | Cleaning and disinfection of collection and waste storage containers and areas; storage area repairs and maintenance | Equipment operation training; design consultations: environmental/waste management, engineering, and architectural design | Sharps and hazardous waste safe handling and disposal training | Disposable waste containers (sharps bins, biohazard bags, etc.); personal protective equipment; waste labeling materials; cleaning and disinfection equipment; spare parts and tools for equipment maintenance and repairs | Point-of-care providers (nurses, technicians, etc.); support staff; cleaners | Compliance monitoring and audits; immunizations for waste handlers | Taxes; interest; utility costs (water, electricity, fuel, etc.); labor and installation fees for equipment | Extra fees or expenses paid to external contractor for any part of the collection, segregation, packaging, and storage process |

| Transportation: pre- and post-treatment | Trolleys, carts, or other equipment for on-site transport; transportation containers; transportation vehicles for off-site transport | Cleaning and disinfection of waste storage containers and transportation equipment; vehicle repairs and maintenance | Equipment operation training; design consultations: environmental/waste management, engineering, and architectural design | Sharps and hazardous waste safe handling and disposal training; safe transport training | Disposable waste containers; personal protective equipment; waste labeling materials; cleaning and disinfection equipment; spare parts and tools for equipment maintenance and repairs; vehicle fuel | Loading/unloading staff; drivers; support staff | Vehicle licensing and insurance; compliance monitoring and audits; immunizations for waste handlers | Taxes; interest | Extra fees or expenses paid to external contractor for any part of the transportation of waste |

| Treatment: incineration, microwaving, autoclave/hydroclave, chemical disinfection, steam sterilization, or dry thermal ‡ | Solid waste treatment equipment; liquid waste treatment equipment; waste shredders; pollution control on incinerators | Cleaning and disinfection of treatment equipment and treatment area; treatment equipment repairs and maintenance | Equipment operation training; design consultations: environmental/waste management, engineering, and architectural design | Sharps and hazardous waste safe handling and disposal training | Disposable components of treatment process; treatment chemicals; personal protective equipment; cleaning and disinfection equipment; spare parts and tools for equipment maintenance and repairs | Treatment plant staff | Treatment plant licensing; incineration air quality emissions testing; compliance monitoring and audits; immunizations for waste handlers | Taxes; interest; utility costs; labor and installation fees for equipment | Extra fees or expenses paid to external contractor for any part of the waste treatment process |

| Final disposal: solid waste landfilling, liquid waste discharge | Landfill/disposal site; sewerage system | Landfill/disposal site repairs and maintenance; sewerage repairs and maintenance | Design consultations: environmental/waste management, engineering, and architectural design | Sharps and hazardous waste safe handling and disposal training | Personal protective equipment | Loading/unloading staff; treatment plant staff | Landfill licensing; compliance monitoring and audits; immunizations for waste handlers | Taxes; interest; landfill fees for solid waste; sewerage fees for liquid waste | Extra fees or expenses paid to external contractor for any part of the final waste disposal process |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, D.M.; Cronk, R.; Best, L.; Radin, M.; Schram, H.; Tracy, J.W.; Bartram, J. Budgeting for Environmental Health Services in Healthcare Facilities: A Ten-Step Model for Planning and Costing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062075

Anderson DM, Cronk R, Best L, Radin M, Schram H, Tracy JW, Bartram J. Budgeting for Environmental Health Services in Healthcare Facilities: A Ten-Step Model for Planning and Costing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(6):2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062075

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Darcy M., Ryan Cronk, Lucy Best, Mark Radin, Hayley Schram, J. Wren Tracy, and Jamie Bartram. 2020. "Budgeting for Environmental Health Services in Healthcare Facilities: A Ten-Step Model for Planning and Costing" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 6: 2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062075

APA StyleAnderson, D. M., Cronk, R., Best, L., Radin, M., Schram, H., Tracy, J. W., & Bartram, J. (2020). Budgeting for Environmental Health Services in Healthcare Facilities: A Ten-Step Model for Planning and Costing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062075