Employees’ Work-Related Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Perspective of Technology Acceptance Model and JD-R Theory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Work Engagement

Job Characteristics and Work Engagement

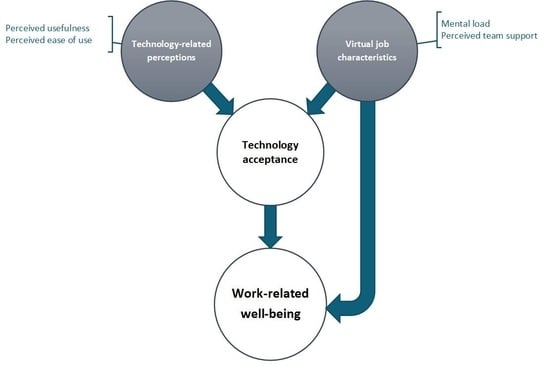

1.2. Technology Acceptance: Antecedents and Work Engagement

1.2.1. Technology-Related Perceptions and Technology Acceptance

1.2.2. Job Characteristics and Technology Acceptance

1.2.3. Technology Acceptance and Work Engagement

1.3. The Mediating Role of Technology Acceptance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Respondents and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

3.2. Structural Model Evaluation

3.3. Tests of Mediation Hypotheses

3.4. Control Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings and Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karlsson, M.; Nilsson, T.; Pichler, S. The impact of the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic on economic performance in Sweden: An Investigation into the consequences of an extraordinary mortality shock. J. Health Econ. 2014, 36, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aassve, A.; Alfani, G.; Gandolfi, F.; Le Moglie, M. Epidemics and trust: The case of the Spanish flu. Health Econ. 2021, 30, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report 86. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200415-sitrep-86-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c615ea20_2 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shigemura, J.; Ursano, R.J.; Morganstein, J.C.; Kurosawa, M.; Benedek, D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-NCOV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, A.; Gorwood, P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Martino, V.; Wirth, L. Telework: A new way of working and living. Int’l Lab. Rev. 1990, 129, 529. [Google Scholar]

- Felstead, A.; Henseke, G. Assessing the growth of remote working and its consequences for effort, well-being and work-life balance. New Technol. Work Employ. 2017, 32, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vander Elst, T.; Verhoogen, R.; Sercu, M.; Van den Broeck, A.; Baillien, E.; Godderis, L. Not extent of telecommuting, but job characteristics as proximal predictors of work-related well-being. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e180–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, D. Good to be Home? Time-use and satisfaction levels among home-based teleworkers. New Technol. Work Employ. 2012, 27, 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher, C.; Anderson, D. Doing More with Less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardeshmukh, S.R.; Sharma, D.; Golden, T.D. Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: A job demands and job resources model. New Technol. Work Employ. 2012, 27, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, A.; Gilliland, A.; Peebles, R.; Rossi, N.; Shrout, T. Telecommuting: Smarter Workplaces. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1811/91648 (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, A.; Barth, E.; Dale-Olsen, H. The effects of organizational change on worker well-being and the moderating role of trade unions. ILR Rev. 2013, 66, 989–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colbert, A.; Yee, N.; George, G. The Digital Workforce and the Workplace of the Future; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murawski, M.; Bick, M. Digital Competences of the Workforce: A Research Topic? Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2017, 23, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Hoeven, C.L.; van Zoonen, W.; Fonner, K.L. The practical paradox of technology: The influence of communication technology use on employee burnout and engagement. Commun. Monogr. 2016, 83, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, J.-C.; Kim, S.; Lee, H. Effect of work-related smartphone use after work on job burnout: Moderating effect of social support and organizational politics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 105, 106194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Tondeur, J. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Comput. Educ. 2019, 128, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reineke, K. The Influence of Digitization on the Emotional Exhaustion of Employees: The Moderating Role of Traditional Job Resources and Age; Paderborn University: Paderborn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale, J.M.; Hoover, C.S. Cell phones during nonwork time: A source of job demands and resources. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeike, S.; Choi, K.-E.; Lindert, L.; Pfaff, H. Managers’ well-being in the digital era: Is it associated with perceived choice overload and pressure from digitalization? An exploratory study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okkonen, J.; Bordi, L.; Mäkiniemi, J.-P.I.; Heikkilä-Tammi, K. Communication in the digital work environment: Implications for wellbeing at work. Nord. J. Work Life Stud. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molino, M.; Cortese, C.G.; Ghislieri, C. The promotion of technology acceptance and work engagement in industry 4. 0: From personal resources to information and training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2438. [Google Scholar]

- Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, G.F.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Wellbeing costs of technology use during COVID-19 remote working: An investigation using the italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, M.; Ingusci, E.; Cortese, C.G.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Manuti, A.; Molino, M.; Signore, F.; Russo, V. Does the end justify the means? The role of organizational communication among work-from-home employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warr, P. The Study of Well-Being, Behaviour and Attitudes. In Psychology at Work; Warr, P., Ed.; Penguin Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rothmann, S. Job satisfaction, occupational stress, burnout and work engagement as components of work-related wellbeing. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2008, 34, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and Measuring Work Engagement: Bringing Clarity to the Concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. Work engagement: What do we know and where do we go? Rom. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 14, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W. Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the job demands-resources model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur. J. Personal. 1987, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, A.; Wientjes, C. Mental load and work stress as two types of energy mobilization. Work Stress 1994, 8, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisopoulos, S.; Dollard, M.F.; Winefield, A.H.; Dormann, C. Increasing the probability of finding an interaction in work stress research: A two-wave longitudinal test of the triple-match principle. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Tooren, M.; De Jonge, J. The role of matching job resources in different demanding situations at work: A vignette study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Salvendy, G. Review and reappraisal of modelling and predicting mental workload in single- and multi-task environments. Work Stress 2000, 14, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Muñoz, E.L.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, R.E. Contribution of mental workload to job stress in industrial workers. Work (Read. Mass.) 2007, 28, 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Omolayo, B.O.; Omole, O.C. Influence of mental workload on job performance. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen, A. Extending the Job Demands-Resources Model: The Relationship between Job Demands and Work Engagement, and the Moderating Role of Job Resources. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- D’Emiljo, A.; Du Preez, R. Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A diagnostic survey of nursing practitioners. Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2017, 19, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G. The effect of emotional dissonance and mental load on need for recovery and work engagement among italian fixed-term researchers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, F. Why has work effort become more intense? Ind. Relat. 2004, 43, 709–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rachinger, M.; Rauter, R.; Müller, C.; Vorraber, W.; Schirgi, E. Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S.L.; Leiter, M.P. Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bishop, J.W.; Scott, K.D.; Burroughs, S.M. Support, commitment, and employee outcomes in a team environment. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chuttur, M.Y. Overview of the technology acceptance model: Origins, developments and future directions. Work Pap. Inf. Syst. 2009, 9, 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- King, W.R.; He, J. A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legris, P.; Ingham, J.; Collerette, P. Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Segars, A.H.; Grover, V. Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness: A confirmatory factor analysis. MIS Q. 1993, 17, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.P.; Sánchez, A.M.; de Luis Carnicer, P.; Jiménez, M.J.V. A technology acceptance model of innovation adoption: The case of teleworking. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2004, 7, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa, G.; Conradie, D.P. Perceptions and attitudes with regard to teleworking among public sector officials in pretoria: Applying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). South Afr. J. Commun. Theory Res. 2003, 29, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razif, M.; Miraja, B.A.; Persada, S.F.; Nadlifatin, R.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Redi, A.A.N.P.; Lin, S.-C. Investigating the role of environmental concern and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology on working from home technologies adoption during COVID-19. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazizadeh, M.; Lee, J.D.; Boyle, L.N. Extending the technology acceptance model to assess automation. Cogn. Technol. Work 2012, 14, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.Y.; Jackson, J.D.; Park, J.S.; Probst, J.C. Understanding information technology acceptance by individual professionals: Toward an integrative view. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer Acceptance of Electronic Commerce: Integrating Trust and Risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathieson, K.; Peacock, E.; Chin, W.W. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model: The Influence of Perceived User Resources. ACM SIGMIS Database 2001, 32, 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Brown, S.A.; Chen, H. Examining the impacts of mental workload and task-technology fit on user acceptance of the social media search system. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.O.; Adkins, M.; Mittleman, D.; Kruse, J.; Miller, S.; Nunamaker Jr, J.F. A technology transition model derived from field investigation of gss use aboard the uss coronado. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1998, 15, 151–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, P.; Heinz, S.; Métrailler, Y.; Opwis, K. Cognitive load in ecommerce applications: Measurement and effects on user satisfaction. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2009, 2009, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, A.; Scott, N.; Kelloway, E.K. Information and Communication Technology: Implications for Job Stress and Employee Well-Being. In New Developments in Theoretical and Conceptual Approaches to Job Stress; Perrewé, P.L., Ganster, D.C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010; pp. 317–350. [Google Scholar]

- A Worker-Centric Design and Evaluation Framework for Operator 4.0 Solutions that Support Work Well-Being. In IFIP Working Conference on HumanWork Interaction Design, Espoo, Finland, 20–21 August 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018.

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Hakanen, J.; Salanova, M.; De Witte, H. An ultra-short measure for work engagement: The uwes-3 validation across five countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 35, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, P.; Kiew, M.-Y. A partial test and development of delone and mclean’s model of is success. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 1996, 4, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lequeurre, J.; Gillet, N.; Ragot, C.; Fouquereau, E. Validation of a french questionnaire to measure job demands and resources. Rev. Int. de Psychol. Soc. 2013, 26, 93–124. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. AMOS User’s Guide Version 3.6; SmallWaters Corporation: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (Multivariate Applications Series); Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 7384. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage Publications Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods 1998, 3, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. An examination of the validity of two models of attitude. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1981, 16, 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, J.; Seubert, C.; Hornung, S.; Herbig, B. The impact of learning demands, work-related resources, and job stressors on creative performance and health. J. Pers. Psychol. 2015, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sawang, S. Is there an inverted u-shaped relationship between job demands and work engagement: The moderating role of social support. Int. J. Manpow. 2012, 33, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Maruping, L.M.; Bala, H. Predicting different conceptualizations of system use: The competing roles of behavioral intention, facilitating conditions, and behavioral expectation. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological Aspects of Workload. In A Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology; Drenth, P.J.D., Thierry, H., de Wolff, C.J., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2013; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Total | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 263 | 44 |

| Female | 330 | 56 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 35 | 6 |

| 30–39 | 118 | 20 | |

| 40–49 | 179 | 30 | |

| 50–59 | 149 | 24 | |

| Over 60 years old | 112 | 20 | |

| University | UiS | 276 | 45 |

| Nord | 115 | 19 | |

| HVL | 219 | 36 | |

| Tenure | 0–5 years | 265 | 45 |

| 6–10 years | 124 | 21 | |

| 11–15 years | 66 | 11 | |

| 16–20 years | 57 | 10 | |

| 21–25 years | 42 | 7 | |

| Over 26 years | 37 | 6 | |

| Education | Bachelor | 10 | 2 |

| Master | 267 | 45 | |

| PhD | 312 | 53 | |

| Main task | Only teaching | 67 | 11 |

| Only research | 94 | 16 | |

| Both teaching and research | 418 | 70 | |

| Other tasks, more than 30% | 22 | 4 | |

| Employment type | Full-time | 525 | 89 |

| Part-time | 67 | 11 |

| Dimension | Items No. | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work engagement | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.53 | |||

| WE1 | At my work, I feel bursting with energy. | 0.65 | ||||

| WE2 | I am enthusiastic about my job. | 0.87 | ||||

| WE3 | I am immersed in my work. | 0.64 | ||||

| Technology acceptance | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.62 | |||

| TA1 | I am satisfied with the performance of these digital tools. | 0.77 | ||||

| TA2 | I am pleased with the experience of using these digital tools. | 0.88 | ||||

| TA3 | Using these digital tools has helped me to improve my work. | 0.70 | ||||

| Perceived ease of use | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.64 | |||

| PEOU1 | My interaction with these digital tools is clear and understandable. | 0.74 | ||||

| PEOU2 | Interacting with these digital tools does not require a lot of mental effort. | 0.73 | ||||

| PEOU3 | I find these digital tools easy to use. | 0.87 | ||||

| PEOU4 | I find it easy to get these digital tools to do what I want them to do. | 0.87 | ||||

| Perceived usefulness | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.81 | |||

| PU1 | Using these digital tools will improve my performance in my job. | 0.82 | ||||

| PU2 | Using these digital tools will improve my productivity in my job. | 0.96 | ||||

| PU3 | Using these digital tools will enhance my effectiveness in my job. | 0.93 | ||||

| Perceived team Support | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.64 | |||

| PTS1 | The department cares about my general satisfaction at work. | 0.88 | ||||

| PTS2 | Even if I did the best job possible, the department would fail to notice. | 0.65 | ||||

| PTS3 | The department really cares about my well-being. | 0.87 | ||||

| PTS4 | The department takes pride in my accomplishments at work. | 0.77 | ||||

| Mental load | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.50 | |||

| ML1 | My work demands much concentration. | 0.71 | ||||

| ML2 | My work requires continual thought. | 0.83 | ||||

| ML3 | I have to give continuous attention to my work. | 0.70 | ||||

| ML4 | My work requires a great deal of carefulness. | 0.55 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work engagement | 3.77 | 0.72 | 0.728 | |||||||

| 2. Technology acceptance | 3.43 | 0.86 | 0.18 ** | 0.787 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived ease of use | 3.75 | 0.93 | 0.15 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.805 | |||||

| 4. Perceived usefulness | 3.13 | 1.11 | 0.14 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.902 | ||||

| 5. Perceived team support | 3.53 | 0.94 | 0.27 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.801 | |||

| 6. Mental load | 4.40 | 0.59 | 0.14 ** | −0.09 * | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.710 | ||

| 7. Gender a | - | - | 0.095 * | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.09 * | 0.03 | 0.11 ** | - | |

| 8. Age a | - | - | 0.04 | −0.11 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.006 | - |

| Indirect Effect | Est. | SE | p | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental load → Technology acceptance → Work engagement | −0.020 | 0.011 | 0.012 | (−0.044, −0.006) |

| Perceived Support → Technology acceptance → Work engagement | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.036 | (0.001, 0.019) |

| Perceived ease of use → Technology acceptance → Work engagement | 0.074 | 0.023 | 0.000 | (0.041, 0.118) |

| Perceived usefulness → Technology acceptance → Work engagement | 0.042 | 0.013 | 0.001 | (0.022, 0.067) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shamsi, M.; Iakovleva, T.; Olsen, E.; Bagozzi, R.P. Employees’ Work-Related Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Perspective of Technology Acceptance Model and JD-R Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211888

Shamsi M, Iakovleva T, Olsen E, Bagozzi RP. Employees’ Work-Related Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Perspective of Technology Acceptance Model and JD-R Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211888

Chicago/Turabian StyleShamsi, Marjan, Tatiana Iakovleva, Espen Olsen, and Richard P. Bagozzi. 2021. "Employees’ Work-Related Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Perspective of Technology Acceptance Model and JD-R Theory" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211888

APA StyleShamsi, M., Iakovleva, T., Olsen, E., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2021). Employees’ Work-Related Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrated Perspective of Technology Acceptance Model and JD-R Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211888