The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Social Impact on Education: Were Engineering Teachers Ready to Teach Online?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim and Scope

2. Materials and Methods

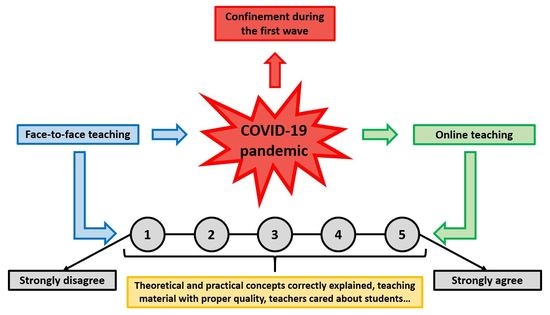

2.1. Experimental Design: Framework and General Marks

- The guidelines that the teachers of the course units selected for the experiment had to follow during the online teaching were established, so that the online teaching was comparable between teachers [50]. These guidelines were of a general nature and each teacher had to adapt to them on the basis of their own knowledge and past experience. The implementation of the experiment was therefore very close to reality [22]. These guidelines are listed in Section 2.2.

- Course units of different types were selected for the experiment, so that they were of a general character [49]. In addition, course units with similar teacher profiles were selected, in order to compare the perceptions of online teaching and F2F teaching [48]. Both these aspects and the process of selecting the course units are explained in detail in Section 2.3.

- The evaluative survey was prepared. This survey regarding F2F teaching was administered to the students on the selected course units in the first week of online classes. At the end of the experiment (last week of online classes), the students responded to the survey on online teaching. In this way, students’ perceptions of both teaching methodologies and a variety of other aspects could be compared. The questions in this survey are listed in Section 2.5.

2.2. Online Teaching Guidelines

2.3. Selected Course Units

- Course units of almost all types from engineering education had to be included.

- The profile of the teacher on each selected course unit had to fit an almost standard one: a specialized teacher with regard to the content of the course unit, with knowledge of new technologies and capable of developing course unit activities online [53]. In addition, the F2F teaching methodology of the teachers had to be similar, so that any effect of the teacher on the comparison between F2F and online teaching could be disregarded [52].

- Students of as many ages as possible should participate.

- Firstly, all course units from all four years of the Bachelor’s Degree in Agroalimentary Engineering & the Rural Environment, the Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering, and the Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering of the University of Burgos were identified. These three university degrees were chosen in representation of all areas of the Higher Polytechnic School of the University of Burgos, with regard to both type of knowledge taught and teaching levels (Bachelor’s Degree and Master’s Degree). Moreover, the authors of this study had formed working relationships of partnership and trust with most of the teachers of these careers, which facilitated their involvement in the experiment.

- Secondly, all the courses were divided into three different groups, according to the type of knowledge that the students are expected to acquire. On the one hand are the Basic Course Units (BCU) that have no engineering-related content, on which concepts of a general nature are taught, such as mathematics, applied sciences and economics. On the other hand are the Design Course Units (DCU) on which technical concepts are taught, such as structural, hydraulic, and thermal theory, as well as computing design. Finally, the Management Course Units (MCU) were selected, on which the future engineers are expected to learn the necessary concepts for professional practice unrelated to engineering design, such as employee management, project timelines, and budgeting. These groups of course units are widely accepted as essential aspects for the training of engineers [47,49].

- In each of these three groups, four course units were selected, which approximately covered the age range of students, from 18 to 24 years old. These course units were selected on the basis of the teachers’ profiles. Their profiles had to fit the one indicated above and the participating teachers had to teach their F2F classes in a similar way, considering such aspects as time dedicated to both theoretical and practical concepts, class methodology, group work, and workload of the qualification. In this way, the students’ perceptions of both F2F and online teaching could be compared on all the selected course units [52]. A comparative process between the available teachers was conducted, to select suitable course units, based on the prior knowledge of the authors, the evaluation surveys from previous years on teaching activity administered to students, and the teaching quality evaluation grade obtained by each teacher of the University of Burgos (DOCENTIA program [54]).

- Finally, the teachers of the selected course units (four in each group, twelve course units in total) were contacted to explain the experiment, its objectives, and what they were expected to do. Agreement was forthcoming from the teachers of five different course units (1 BCU, 2 DCU, and 2 MCU)—a response that was considered acceptable, in view of the social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (family and professional life balance, confinement, teleworking …) that had recently begun to make themselves felt in Spain [30].

- Business Economics II, a BCU on the 2nd year of the Bachelor’s Degree in Agroalimentary Engineering & the Rural Environment.

- Construction & Agroalimentary Building, a DCU on the 3rd year of the Bachelor’s Degree in Agroalimentary Engineering & the Rural Environment.

- Engineering of Green Spaces, a DCU on the 4th year of the Bachelor’s Degree in Agroalimentary Engineering & the Rural Environment.

- Project and Construction Management, an MCU on the 3rd year of the Bachelor’s Degree in Civil Engineering.

- Engineering Projects, an MCU on the 1st year of the Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering.

2.4. Participants

2.5. Instrument: Survey

- The theoretical concepts have been properly explained.

- I would be able to face a real problem related to the course work with the theoretical knowledge that I have learnt.

- It was easy for me to understand the theoretical concepts explained in class.

- The practical concepts have been properly explained.

- My practical knowledge will be sufficient to deal with a real problem related to the course unit.

- It was easy for me to understand the practical concepts explained in class.

- The material provided was prepared for the type of teaching received.

- The teaching material had been carefully prepared in the right format.

- All material provided was necessary for a proper understanding of the course unit.

- It was easy to enter into contact with the teacher and to clarify doubts.

- The teacher responded to all doubts that were raised regardless of their nature, even if so-called “silly questions” were asked.

- The teacher quickly responded to the doubts as they were raised.

- If you communicated with the teacher at some point, how did you do so (F2F, email, Skype, Microsoft Teams …)? The answer to this question was analyzed as a qualitative variable (see Section 2.6).

- I felt that the teacher was concerned that students would understand the concepts that had been explained.

- The teacher continuously monitored the understanding of the concepts that had been explained, for example, by asking whether students had understood them.

- Teachers showed sympathetic attitudes towards project assignment completion dates, mainly when handed in late.

- The course was difficult to understand.

- The course was difficult to pass.

- I have learned a lot during the course.

- The course required a lot of work.

- If you think that they exist, indicate the advantages/disadvantages of the online teaching compared to the F2F teaching or vice versa. What shortcomings if any did you associate with each teaching methodology?

2.6. Analysis Performed

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Numerical Rating Statements: Average Values and Confidence Intervals

3.1.1. Explanation and Learning of Theoretical Concepts: Statements 1–3

3.1.2. Explanation and Learning of Practical Concepts: Statements 4–6

- The results were worse than for the theoretical concepts, reflected by the lower valuations of statements 4 and 6 at around 0.4 points. It confirms that it is more difficult to achieve a correct explanation and understanding of practical concepts in online teaching.

- Figure 2a shows that the best results in this section were for the DCU, regardless of the type of teaching. These course units generally have a highly practical focus, and it is usual for the teacher to emphasize design concepts [53], an attitude that was maintained during the online teaching, which meant that the DCU obtained the highest score in this section.

- The overall rating of statement 5 in online teaching was only 0.1 points lower than F2F teaching (see Figure 2b). The difference in statement 2 (application of theoretical concepts in the professional field) was 0.2 points. The teachers usually linked the solutions of the exercises to aspects of the professional world in which they are experienced [63]. Although this practice is more difficult in online than in F2F teaching, it was observed that the teachers maintained it more easily than in the explanation of theoretical concepts.

3.1.3. Quality of Teaching Material: Statements 7–9

3.1.4. Teacher’s Availability to Communicate with Students: Statements 10–12

3.1.5. Students’ Assessment of Teachers’ Attitudes during Teaching: Statements 14–16

3.1.6. Overall Perception of the Course: Statements 17–20

- Firstly, as expected [13], the students considered that the course unit concepts were more difficult to understand in online teaching. The lack of familiarity with online teaching among both students and teachers may mean that globally the concepts were slightly less well explained [22]. It also meant that students thought they had learned less through online teaching [50]. However, the difference between both types of teaching was very small, due to the aspects highlighted in previous sections.

- Various studies have shown that if a course is graded in online mode in the same way as in F2F, the online grades are clearly lower [66]. It is therefore essential that grading methods are adjusted to the type of teaching [58]. For these reasons, the analysis of course-unit difficulty yielded surprising results, because the students considered it similar in both types of teaching. In addition, the DCU taught online were considered easier to pass. When asked, teachers indicated that the grading method had to be adapted in the middle of the term, after receiving some guidelines from the University for the conversion to virtual teaching and, especially, to fully online assessment. Moreover, some common strategies were detected: the relevance of the exam in the final grade was reduced in all courses, and the weight of the project assignments was increased. As commented upon with regard to other aspects, the teachers also showed a great capability to adapt the grading method of the course unit to the existing situation. It is important to point out that in no way could the design of the experiment be said to condition the grading of the courses (see Section 2.3).

- In line with the above, the students never indicated that the workload varied much between both types of teaching, although it was slightly higher in online teaching. In this type of teaching, the time spent memorizing content in the absence of classroom learning processes is greater than in F2F teaching [30]. However, the relevance of the exam in the final grade was decreased in all the courses, which reduced the need for memorization. In this way, students spent more time on project assignments, work that they considered more enjoyable and that may have given them the impression of a lighter workload.

3.2. Numerical Rating Statements: Effect of the Factors, Two-Way ANOVA

3.3. Channels of Communication between the Teacher and the Students

- On the one hand, the DCU contained the most engineering design-related concepts that have to be explained [47]. This type of course unit therefore has aspects that are difficult for students to understand [65], which means that F2F communication is very common (according to Figure 7c, 4 out of every 10 students used it) during F2F teaching. In turn, web tools were the most frequently used communication channel among those students (5 out of every 10 students) during online teaching, because it is the closest to F2F communication that can be used over a distance [57]. The use of email also increased (from 3 to 4 out of every 10 students), while the number of students who presented no doubts was practically negligible.

- On the other hand, the teacher’s personal preferences also influenced the communication channel in use. The BCU was the only course unit in which the chats available on the teacher support platform were used by students (see Figure 7a,b), meanwhile the increased use of email, from 4 to 8 out of every 10 students, was very notable in the MCU (see Figure 7e,f). In view of this situation, all the teachers who participated in the experiment were asked if they had promoted the use of some specific communication channel. The BCU teachers indicated that they had encouraged students to communicate via the MOODLE platform chat option. In their opinion, it was similar to email as a means of communication, but they could control the resolution of doubts in a simpler and more effective way, as the finding of other studies have also shown [71]. Furthermore, MCU teachers indicated that they had promoted the use of email because it allowed them to better reconcile their teaching activity with family life.

3.4. Global Opinion of Students

3.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

“I believe that the main disadvantage of online teaching has been the difficulty with understanding the practical exercises.”(DCU)

“The communication with the teacher is not as frequent and easy in online teaching as during F2F teaching. In F2F teaching you can ask the teacher about your doubts while they are explaining the exercise.”(BCU)

“I think that the contact with my classmates is beneficial to know their point of view and understand the concepts better.”(DCU)

“I think that in F2F teaching you get a better overall learning experience.”(MCU)

“F2F teaching forces you to follow a study routine that is beneficial for keeping the course up to date.”(MCU)

“I liked videos explaining the concepts that the teacher provided. In this way, I have been able to follow the course as I wanted and study when it was most convenient for me.”(DCU)

“The teacher has positively adapted the course to the confinement situation. He has sent us weekly work that is not excessive and that has meant we can stay up to date with the course unit without too much stress.”(BCU)

“I would like to thank the flexibility of the teacher when responding to our doubts. She has constantly helped us.”(DCU)

“I am happy with the teacher and with the way she has managed the course during this lockdown period. Her monitoring during the online teaching has also been very useful.”(MCU)

“The teacher has always been attentive to the students and their doubts.”(DCU)

3.4.2. Mixed Analysis

3.5. Limitations of the Study

- On the one hand, although the types of course units under analysis were the most common, the large number of existing engineering careers meant that some types of course units were not studied in this research work [49]. Therefore, the results of this study should not be considered valid for all course units, as a detailed study may be necessary in some of them.

- On the other, only the students’ opinions were analyzed. The teachers’ reflections on teaching engineering during the lockdown due to the pandemic were not evaluated. Doing so evaluated whether the teachers were able to adapt correctly to online teaching, but not how they did it [50].

4. Conclusions

- Students considered that the explanations of theoretical concepts were more successful during F2F teaching, except in the basic course units taught in the first years of engineering degrees. The reduced learning autonomy of the recently enrolled students increased the concerns over the explanation of these types of concepts among the teachers [47].

- Despite the need for teachers to balance family and professional life [7], the students indicated that the teaching material provided was prepared in detail, and was adequately adapted to online teaching. In addition, the documentation was not in excess, which is a common problem when teaching online [48].

- The attitude of the teachers towards the students was attentive, expressing constant concern for their learning. The basic course units experienced a notable improvement in this aspect, because students in the first years of their careers were more dependent on the teacher in their learning [62].

- Course unit grades were not influenced by the abrupt change in the teaching modality, due to the way that the teachers had adapted the evaluation system. An online course unit that is graded in the same way as a F2F course will usually result in significantly lower grades [66].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Weert, H. After the first wave: What effects did the COVID-19 measures have on regular care and how can general practitioners respond to this? Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 26, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.A.M.; Austin, Z. COVID-19: How did community pharmacies get through the first wave? Can. Pharm. J. 2020, 153, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, G. Social distancing versus early detection and contacts tracing in epidemic management. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, J.; Mohr, L.; Tenforde, A.S.; Edouard, P.; Fossati, C.; González-Gross, M.; Ramirez, C.S.; Laiño, F.; Tan, B.; Pillay, J.D.; et al. Restrictercise! preferences regarding digital home training programs during confinements associated with the covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashford, N.A.; Hall, R.P.; Arango-Quiroga, J.; Metaxas, K.A.; Showalter, A.L. Addressing inequality: The first step beyond COVID-19 and towards sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calavia, M.Á.G.; Cárdenas, J.; Barbeito Iglesias, R.L. Introduction to the controversy: Social impacts of the COVID-19: A new challenge for sociology. Rev. Esp. Sociol. 2020, 29, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moti, U.G.; Goon, D.T. Novel coronavirus disease: A delicate balancing act between health and the economy. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S134–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martarelli, C.S.; Wolff, W. Too bored to bother? Boredom as a potential threat to the efficacy of pandemic containment measures. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsali, M.E.; Mousa, D.P.V.; Papadopoulou, E.V.K.; Papadopoulou, K.K.K.; Kaparounaki, C.K.; Diakogiannis, I.; Fountoulakis, K.N. University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzek, D.; Skolmowska, D.; Głabska, D. Analysis of gender-dependent personal protective behaviors in a national sample: Polish adolescents’ covid-19 experience (place-19) study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.M.D. The relationship between the covid-19 pandemic and nursing students’ sense of belonging: The experiences and nursing education management of pre-service nursing professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gressman, P.T.; Peck, J.R. Simulating COVID-19 in a university environment. Math. Biosci. 2020, 328, 108436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Cao, S.; Li, H. Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayter, M.; Jackson, D. Pre-registration undergraduate nurses and the COVID-19 pandemic: Students or workers? J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3115–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monforte-Royo, C.; Fuster, P. Coronials: Nurses who graduated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Will they be better nurses? Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 94, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula, J.R. Lockdowns due to COVID-19 threaten PhD students’ and early-career researchers’ careers. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.M.D. How does covid-19 pandemic influence the sense of belonging and decision-making process of nursing students: The study of nursing students’ experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, J.K.; Pate, A.N. The Impact of COVID-19 through the Eyes of a Fourth-Year Pharmacy Student. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omary, M.B.; Eswaraka, J.; Kimball, S.D.; Moghe, P.V.; Panettieri, R.A.; Scotto, K.W. The COVID-19 pandemic and research shutdown: Staying safe and productive. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2745–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloom, D.A.; Reid, J.R.; Cassady, C.I. Education in the time of COVID-19. Pediatr. Radiol. 2020, 50, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, T.A.; Mc Carthy, P.; Mc Govern, R.; Slattery, S.; Yates, J.; Murphy, S. The impact of COVID-19 on medical student education—Navigating uncharted territory. Ir. Med. J. 2020, 113, P109. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, N. Transforming online teaching and learning: Towards learning design informed by information science and learning sciences. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelhauser, E.; Lupu-Dima, L. Is Romania prepared for elearning during the COVID-19 pandemic? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M.C.R.; Frutuoso, L.; Benevides, S.S.N.; Barreira, N.H.M.; Silva, J.L.G.; Pereira, M.C.; Cecilio-Fernandes, D. The challenges and benefits of online teaching about diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasawneh, A.I.; Humeidan, A.A.; Alsulaiman, J.W.; Bloukh, S.; Ramadan, M.; Al-Shatanawi, T.N.; Awad, H.H.; Hijazi, W.Y.; Al-Kammash, K.R.; Obeidat, N.; et al. Medical Students and COVID-19: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Precautionary Measures. A Descriptive Study from Jordan. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Hira, A. Loss of brick-and-mortar schooling: How elementary educators respond. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Tlili, A.; Chang, T.W.; Zhang, X.; Nascimbeni, F.; Burgos, D. Disrupted classes, undisrupted learning during COVID-19 outbreak in China: Application of open educational practices and resources. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.H.; Luong, D.H.; Nguyen, X.A.; Nguyen, H.L.; Ngo, T.T. Impact of female students’ perceptions on behavioral intention to use video conferencing tools in COVID-19: Data of Vietnam. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohmmed, A.O.; Khidhir, B.A.; Nazeer, A.; Vijayan, V.J. Emergency remote teaching during Coronavirus pandemic: The current trend and future directive at Middle East College Oman. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Leal-Costa, C.; Moral-García, J.E.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M. Experiences of nursing students during the abrupt change from face-to-face to e-learning education during the first month of confinement due to COVID-19 in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E. School librarians online: Integrated learning beyond the school walls. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Aguglia, A.; Bianchi, D.; Santi, F.; Costantini, L.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; et al. Covid-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; An, Y.; Tan, X.; Li, X. Mental Health and Its Influencing Factors among Self-Isolating Ordinary Citizens during the Beginning Epidemic of COVID-19. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, H. The Impact of COVID-19 on Anxiety in Chinese University Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.J.; Wang, L.L.; Yang, R.; Yang, X.J.; Zhang, L.G.; Guo, Z.C.; Chen, J.C.; Wang, J.Q.; Chen, J.X. Sleep problems among Chinese adolescents and young adults during the coronavirus-2019 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020, 74, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorca, M.; Martínez-Lorca, A.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J.; Armesilla, M.D.C.; Latorre, J.M. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Validation in spanish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathabhavan, R.; Griffiths, M. First case of student suicide in India due to the COVID-19 education crisis: A brief report and preventive measures. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balhara, Y.P.S.; Kattula, D.; Singh, S.; Chukkali, S.; Bhargava, R. Impact of lockdown following COVID-19 on the gaming behavior of college students. Indian J. Public Health 2020, 64, S172–S176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T.K. COVID-19: Consequences for higher education. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenei, K.; Cassidy-Matthews, C.; Virk, P.; Lulie, B.; Closson, K. Challenges and opportunities for graduate students in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 408–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goghari, V.M.; Hagstrom, S.; Madon, S.; Messer-Engel, K. Experiences and learnings from professional psychology training partners during the covid-19 pandemic: Impacts, challenges, and opportunities. Can. Psychol. 2020, 61, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, P. Contactless u: Higher education in the postcoronavirus world. Computer 2020, 53, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colao, A.; Piscitelli, P.; Pulimeno, M.; Colazzo, S.; Miani, A.; Giannini, S. Rethinking the role of the school after COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Díaz, L.; Fernandez-Caminero, G.; Hernandez-Lloret, C.M.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, H.; Alvarez-Castillo, J.L. Analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on education professionals. Toward a paradigm shift: ICT and neuroeducation as a binomial of action. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, B.M. Will virtual teaching continue after the COVID-19 pandemic? Acta Med. Port. 2020, 33, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Skaf, M.; Manso, J.M.; Ortega-López, V. Student perceptions of formative assessment and cooperative work on a technical engineering course. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, S.; Kandimalla, S.R.; Cao, M.; Maronna, I.; An, H.; Bogart, C.; Murray, R.C.; Hilton, M.; Sakr, M.; Penstein Rosé, C. Designing for learning during collaborative projects online: Tools and takeaways. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang-Saad, A.Y.; Morton, C.S.; Libarkin, J.C. Entrepreneurship Assessment in Higher Education: A Research Review for Engineering Education Researchers. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, C. Collaborating in online teaching: Inviting e-guests to facilitate learning in the digital environment. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.H.; Gallen, A.M. Peer observation, feedback and reflection for development of practice in synchronous online teaching. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2016, 53, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayathirtha, G.; Fields, D.; Kafai, Y.B.; Chipps, J. Supporting making online: The role of artifact, teacher and peer interactions in crafting electronic textiles. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Joy, S. Learning attitudes and resistance to learning language in engineering students. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 2085–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación (ANECA), DOCENTIA Program. Available online: http://www.aneca.es/Programas-de-evaluacion/Evaluacion-institucional/DOCENTIA (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Seifan, M.; Dada, O.D.; Berenjian, A. The effect of real and virtual construction field trips on students’ perception and career aspiration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, R.A., Jr.; Rice, M.; Yang, S.; Jackson, H.A. Self-regulated learning in online learning environments: Strategies for remote learning. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L.; Moorhouse, B.L. Facilitating Synchronous Online Language Learning through Zoom. RELC J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, R.; Quintana, C. When classroom interactions have to go online: The move to specifications grading in a project-based design course. Inform. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-García, C.; Pérez-Pueyo, A.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, M.; Palacios-Picos, A. Teacher trainers’ and trainees’ perceptions of teaching, assessment and development of competences at teacher training colleges. Cult. Educ. 2011, 23, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L.; Doumas, K. Contextual and Analytic Qualities of Research Methods Exemplified in Research on Teaching. Qual. Inq. 2013, 19, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzner, A.; Stucken, K. Reporting on sustainable development with student inclusion as a teaching method. Int. J. Manage. Educ. 2020, 18, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, L.; Yin, J.; Nie, Y. A comparison of flipped and traditional classroom learning: A case study in mechanical engineering. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 1876–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Lakin, J.M.; Wittig, A.H.; Davis, E.W.; Davis, V.A. Am I an engineer yet? Perceptions of engineering and identity among first year students. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Cardella, G.M.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Psychological factors that lessen the impact of covid-19 on the self-employment intention of business administration and economics’ students from latin america. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ní Fhloinn, E.; Carr, M. Formative assessment in mathematics for engineering students. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 42, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdullah, N.A.; Mirza, M.S. Evaluating pre-service teaching practice for online and distance education students in Pakistan. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2020, 21, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ezhov, S.G.; Komarova, N.M.; Khairullina, E.R.; Rapatskaia, L.A.; Miftakhov, R.R.; Khusainova, L.R. Practical recommendations for the development and implementation of youth policy in the university as a tool for development of student public associations. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 9169–9178. [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Skaf, M.; Espinosa, A.B.; Santamaría, A.; Ortega-López, V. Statistical approach for the design of structural self-compacting concrete with fine recycled concrete aggregate. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Jefferson, D.; Broussard, L.; Fox-McCloy, H. Determining roles and best practices when using academic coaches in online learning. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2020, 15, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abella-García, V.; Delgado-Benito, V.; Ausín-Villaverde, V.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D. To tweet or not to tweet: Student perceptions of the use of Twitter on an undergraduate degree course. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 56, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, P.; von Davier, A.; Chamberlain, J.; Koon, A.; Andrews, J.; McIntyre, C. Teaching Teamwork: Electronics Instruction in a Collaborative Environment. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2017, 41, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Course | Number of Students | Mean Age of Students |

|---|---|---|

| Business Economics II | 19 | 20.09 ± 1.04 |

| Basic Course Units (BCU) | 19 | 20.09 ± 1.04 |

| Construction & Agroalimentary Building | 17 | 21.70 ± 2.41 |

| Engineering of Green Spaces | 9 | 22.75 ± 1.50 |

| Design Course Units (DCU) | 26 | 22.00 ± 2.18 |

| Project and Construction Management | 14 | 20.88 ± 0.99 |

| Engineering Projects | 7 | 23.75 ± 1.59 |

| Management Course Units (MCU) | 21 | 22.14 ± 2.14 |

| Statement | p-Value. Factor: Course Type (BCU/DCU/MCU) | Homogeneous Groups. Factor: Course Type (BCU/DCU/MCU) | p-Value. Factor: Teaching Type (F2F/Online) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.1625 | - | 0.4956 |

| 2 | 0.2459 | - | 0.2409 |

| 3 | 0.7707 | - | 0.3305 |

| 4 | 0.3530 | - | 0.1162 |

| 5 | 0.1198 | - | 0.5329 |

| 6 | 0.8408 | - | 0.0395 |

| 7 | 0.3847 | - | 1.0000 |

| 8 | 0.1033 | - | 0.5227 |

| 9 | 0.6482 | - | 0.8789 |

| 10 | 0.3095 | - | 1.0000 |

| 11 | 0.8764 | - | 1.0000 |

| 12 | 0.1122 | - | 0.8531 |

| 14 | 0.0002 | BCU and MCU | 0.7221 |

| 15 | 0.0107 | DCU and MCU | 0.7023 |

| 16 | 0.0004 | DCU and MCU | 0.1376 |

| 17 | 0.3970 | - | 0.4663 |

| 18 | 0.1495 | - | 1.0000 |

| 19 | 0.6904 | - | 0.0289 |

| 20 | 0.0124 | DCU and MCU | 0.5256 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Skaf, M.; Varona, J.M.; Ortega-López, V. The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Social Impact on Education: Were Engineering Teachers Ready to Teach Online? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042127

Revilla-Cuesta V, Skaf M, Varona JM, Ortega-López V. The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Social Impact on Education: Were Engineering Teachers Ready to Teach Online? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):2127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042127

Chicago/Turabian StyleRevilla-Cuesta, Víctor, Marta Skaf, Juan Manuel Varona, and Vanesa Ortega-López. 2021. "The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Social Impact on Education: Were Engineering Teachers Ready to Teach Online?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 2127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042127

APA StyleRevilla-Cuesta, V., Skaf, M., Varona, J. M., & Ortega-López, V. (2021). The Outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic and its Social Impact on Education: Were Engineering Teachers Ready to Teach Online? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 2127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042127