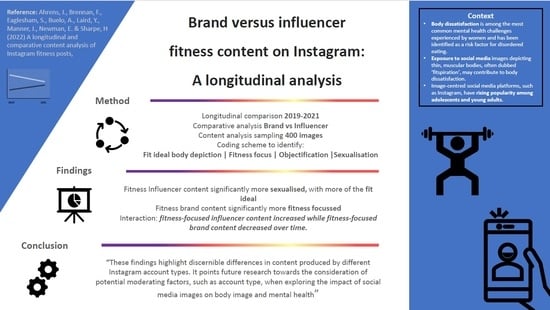

A Longitudinal and Comparative Content Analysis of Instagram Fitness Posts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Coding Procedures

2.4. Coding Attributes

2.4.1. Image Type and Content

2.4.2. Image Purpose

2.4.3. Body Depiction

2.5. Intercoder Reliability

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. RQ1: To What Extent do Rates of Fit Ideal Depiction, Fitness Focus, Objectification, and Sexualisation Differ between Influencer Content and Brand Content?

3.3. RQ2: To What Extent Have Rates of Fit Ideal Depiction, Fitness Focus, Objectification, and Sexualisation in Instagram Fitness Content Changed between 2019 and 2021?

3.4. RQ3: Are There Any Temporal Changes in Fit Ideal Depiction, Fitness Focus, Objectification, and/or Sexualisation That Vary between Influencers and Brands?

4. Discussion

4.1. This Work

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grabe, S.; Ward, L.M.; Hyde, J.S. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreiro, F.; Seoane, G.; Senra, C. Toward understanding the role of body dissatisfaction in the gender differences in depressive symptoms and disordered eating: A longitudinal study during adolescence. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.; Irwin, L.; Newton-John, T.; Slater, A. Bodypositivity: A content analysis of body positive accounts on Instagram. Body Image 2019, 29, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grogan, S. Body Image: Understanding Body Dissatisfaction in Men, Women and Children, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.S.; Kim, H.S. Body-image dissatisfaction as a predictor of suicidal ideation among Korean boys and girls in different stages of adolescence: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C.N.; Durant, S. Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Griffiths, S.; Hay, P.; Mitchison, D.; Mond, J.M.; McLean, S.A.; Rodgers, B.; Massey, R.; Paxton, S.J. Sex differences in the relationships between body dissatisfaction, quality of life and psychological distress. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental Disorders: DSM 5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, P.; Stice, E.; Marti, C.N. Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: Implications for prevention efforts. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharpe, H.; Patalay, P.; Choo, T.H.; Wall, M.; Mason, S.M.; Goldschmidt, A.B.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Bidirectional associations between body dissatisfaction and depressive symptoms from adolescence through early adulthood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M. Sociocultural perspectives on human appearance and body image. In Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention; Cash, T.F., Smolak, L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, E.; Diedrichs, P.C. Influence of the media. In Oxford Handbook of the Psychology of Appearance; Rumsey, N., Harcourt, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, S.; Taki, S.; Laird, Y.; Love, P.; Wen, L.M.; Rissel, C. Cultural adaptations of obesity-related behavioral prevention interventions in early childhood: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, C.; Karazsia, B.T. The effect of thin and muscular images on women’s body satisfaction. Body Image 2015, 13, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; Slater, A. NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. The mediating role of appearance comparisons in the relationship between media usage and self-objectification in young women. Psychol. Women Q. 2015, 39, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckel, L.; Hill, M. Look @ Me 2.0: Self-sexualization in Facebook photographs, body surveillance and body image. Sex Cult. 2017, 21, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrotte, E.R.; Prichard, I.; Lim, M.S. “Fitspiration” on Social Media: A Content Analysis of Gendered Images. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deighton-Smith, N.; Bell, B.T. Objectifying fitness: A content and thematic analysis of fitspiration images on social media. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2018, 7, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maguire, J.S. Body lessons: Fitness publishing and the cultural production of the fitness consumer. Int. Rev. Sport Sociol. 2002, 37, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, B.; Kelly, B.; Baur, L.; Chapman, K.; Chapman, S.; Gill, T.; King, L. Digital junk: Food and beverage marketing on Facebook. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e56–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, K.; Borleis, E.; Brennan, L.; Reid, M.; McCaffrey, T.; Lim, M. What people “like”: Analysis of social media strategies used by food industry brands, lifestyle brands, and health promotion organizations on Facebook and Instagram. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godefroy, J. Recommending Physical Activity during the COVID-19 Health Crisis. Fitness Influencers on Instagram. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 589813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogue, J.V.; Mills, J.S. The effects of active social media engagement with peers on body image in young women. Body Image 2019, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perloff, R.M. Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles 2014, 71, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikoos, T.D.; Buzwell, S.; Sharp, G.; Rossell, S.L. The COVID-19 pandemic: Psychological and behavioral responses to the shutdown of the beauty industry. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branley-Bell, D.; Talbot, C.V. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK lockdown on individuals with experience of eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Internet Celebrity: Understanding Fame Online. Eur. J. Commun. 2018, 33, 696–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutley, S.K.; Falise, A.M.; Henderson, R.; Apostolou, V.; Mathews, C.A.; Striley, C.W. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Disordered Eating Behavior: Qualitative Analysis of Social Media Posts. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e26011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Roberts, T.A. Objectification theory. Psychol. Women Q. 1997, 21, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartky, S.L. Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression; Routledge: London, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780415901864. [Google Scholar]

- Smolak, L.; Murnen, S.K.; Myers, T.A. Sexualizing the self: What college women and men think about and do to be “sexy”. Psychol. Women Q. 2014, 38, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Hendler, L.M.; Nilsen, S.; O’Barr, J.F.; Roberts, T. Bringing back the body: A retrospective on the development of objectification theory. Psychol. Women Q. 2011, 35, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, J.S. Effects of sexually objectifying media on self-objectification and body surveillance in undergraduates: Results of a 2-year panel study. J. Commun. 2006, 56, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxier, B.; Anderson, M. Social Media Use in 2021. Pew Research Centre. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Cash, T.F.; Cash, D.W.; Butters, J.W. ‘Mirror, mirror, on the wall?’: Contrast effects and self-evaluations of physical attractiveness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1983, 9, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinberg, L.J.; Thompson, J.K. Body image and televised images of thinness and attractiveness: A controlled laboratory investigation. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 14, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, Y.; Manner, J.; Buelo, A.; Jepson, R. An Evaluation of Participation Levels and Media Representation of Girls and Women in Sport and Physical Activity in Scotland; The Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy: Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boepple, L.; Ata, R.N.; Rum, R.; Thompson, J.K. Strong is the new skinny: A content analysis of fitspiration websites. Body Image 2016, 17, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaznavi, J.; Taylor, L.D. Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of thinspiration images on popular social media. Body Image 2015, 14, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prichard, I.; Tiggemann, M. Relations among exercise type, self-objectification, and body image in the fitness centre environment: The role of reasons for exercise. Psychol. Sport Exer. 2008, 9, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasylkiw, L.; Emms, A.A.; Meuse, R.; Poirier, K.F. Are all models created equal? A content analysis of women in advertisements of fitness versus fashion magazines. Body Image 2009, 6, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, D.; Tantleff-Dunn, S.; Jentsch, F. Social comparison and the ‘circle of objectification’. Sex Roles 2012, 67, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Sabik, N.J. Integrating social comparison theory and self-esteem within objectification theory to predict women’s disordered eating. Sex Roles 2010, 63, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, L.R.; Donovan, C.L.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Bell, H.S.; Ramme, R.A. The fit beauty ideal: A healthy alternative to thinness or a wolf in sheep’s clothing? Body Image 2018, 25, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozsik, F.; Whisenhunt, B.L.; Hudson, D.L.; Bennett, B.; Lundgren, J.D. Thin is in? Think again: The rising importance of muscularity in the thin ideal female body. Sex Roles 2018, 79, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C.; Lee, J.; Barbetta, T.; Miao, W.S. Influencers and COVID-19: Reviewing key issues in press coverage across Australia, China, Japan, and South Korea. Media Int. Aust. 2021, 178, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, R.; Thompson, J.K. Sexual self-esteem in American and British college women: Relations with self-objectification and eating problems. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Account Type | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influencer | Brand | 2019 | 2021 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Fit Ideal (n = 348) Yes No Total | 123 59 182 | 67.6 32.4 100 | 46 120 166 | 27.7 72.3 100 | 87 85 172 | 50.6 49.4 100 | 82 94 176 | 46.6 53.4 100 |

| Fitness Focus (n = 400) Yes No Total | 66 134 200 | 33 67 100 | 121 79 200 | 60.5 39.5 100 | 94 106 200 | 47 53 100 | 93 107 200 | 46.5 53.5 100 |

| Sexualisation (n = 348) Yes No Total | 64 118 182 | 35.2 64.8 100 | 1 165 166 | 0.6 99.4 100 | 29 143 172 | 16.9 83.1 100 | 36 140 176 | 20.5 79.5 100 |

| Objectification (n = 348) Yes No Total | 39 143 182 | 21.4 78.6 100 | 20 146 166 | 12 88 100 | 21 151 172 | 12.2 87.8 100 | 38 138 176 | 21.6 78.4 100 |

| β | S.E. | p | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I. for Odds Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Fit Ideal | Year | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.969 | 1.01 | 0.54 | 1.89 |

| Account Type | −1.40 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.46 | |

| Year x Account type | −0.65 | 0.48 | 0.175 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 1.33 | |

| Constant | 0.73 | 0.23 | 0.002 | 2.07 | |||

| Fitness Focus | Year | 0.74 | 0.31 | 0.017 | 2.09 | 1.14 | 3.81 |

| Account Type | 1.90 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 6.68 | 3.59 | 12.41 | |

| Year x Account type | −1.46 | 0.43 | 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.54 | |

| Constant | −1.10 | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.33 | |||

| Objectification | Year | 0.88 | 0.39 | 0.022 | 2.413 | 1.13 | 5.13 |

| Account Type | −0.33 | 0.47 | 0.486 | 0.721 | 0.29 | 1.81 | |

| Date x account type | −0.57 | 0.62 | 0.353 | 0.565 | 0.17 | 1.89 | |

| Constant | −1.82 | 0.31 | <0.001 | 0.162 | |||

| Sexualisation | Year | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.486 | 1.24 | 0.67 | 2.29 |

| Account Type | −3.71 | 1.03 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.18 | |

| Year x Account type | −16.98 | 4493.71 | 0.997 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Constant | −0.73 | 0.23 | 0.002 | 0.48 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahrens, J.; Brennan, F.; Eaglesham, S.; Buelo, A.; Laird, Y.; Manner, J.; Newman, E.; Sharpe, H. A Longitudinal and Comparative Content Analysis of Instagram Fitness Posts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6845. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116845

Ahrens J, Brennan F, Eaglesham S, Buelo A, Laird Y, Manner J, Newman E, Sharpe H. A Longitudinal and Comparative Content Analysis of Instagram Fitness Posts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6845. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116845

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhrens, Jacqueline, Fiona Brennan, Sarah Eaglesham, Audrey Buelo, Yvonne Laird, Jillian Manner, Emily Newman, and Helen Sharpe. 2022. "A Longitudinal and Comparative Content Analysis of Instagram Fitness Posts" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6845. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116845

APA StyleAhrens, J., Brennan, F., Eaglesham, S., Buelo, A., Laird, Y., Manner, J., Newman, E., & Sharpe, H. (2022). A Longitudinal and Comparative Content Analysis of Instagram Fitness Posts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6845. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116845