Why They Stayed and Why They Left—A Case Study from Ellicott City, MD after Flash Flooding

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Participants and Interviewing Strategy

2.3. Phenomenological Analysis

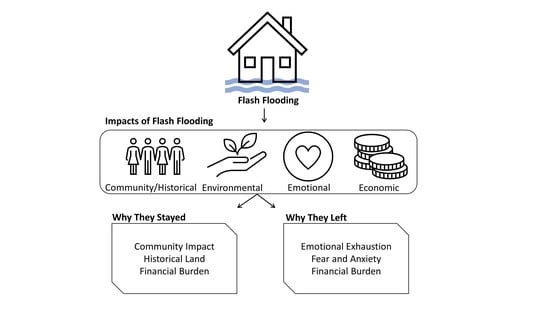

3. Results

3.1. Why Do They Stay?

3.1.1. Theme 1: Community Impact

“When you go through something traumatic…you make friends out of distress and those friendships are deeper and more meaningful…you know, I’m helping people throw out their only copies of their children’s baby photos…I think it’s a level of intimacy that you usually only have with close friends.”(8503)

“The biggest, the reason why we stay is that…there’s something to be said about people who have been through the same experience that you have. We all have PTSD here—we do. We know it, and folks who know what it is, who have been through it as well, they understand… And it’s a support network, and emotionally, for me, it was important to stay.”(7489)

3.1.2. Theme 2: Historical Land

3.1.3. Theme 3: Financial Burdens

3.2. Why Do They Leave?

3.2.1. Theme 1: Emotional Exhaustion and Frustration

“I don’t talk to a lot of the homeowners, the renters, the business owners anymore. I used to be very close with them, so in 2016, it was very devastating because I knew all these people. I visited their houses, and I hung out with them…so the 2016 flood was very devasting just being in this community, seeing how it just broke everyone…I have a sense of detachment I think from the town now because I don’t want to be fully invested anymore because it’s exhausting going through two [floods]…I don’t want to be emotionally invested in this town anymore, or at least Old Ellicott City anymore, because I don’t want to have to feel that again.”(7395)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Fear/Anxiety

“I have a lot of mixed feelings about it. I was really sad to lose my town. I was really sad to have to walk away. I really felt defeated… On the other hand, I was very grateful and I realize that I’m really lucky… not having that ongoing worry. We can sleep through the night when it rains. Whereas we never could before [we moved away].”(8503)

3.2.3. Theme 3: Financial Burdens

4. Discussion

4.1. Community/Historical

4.2. Environmental

4.3. Emotional

4.4. Economic

4.5. Limitations and Advantages

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doheny, E.J.; Nealen, C.W. Storms and Floods of July 30, 2016 and May 27, 2018, in Ellicott City, Howard County, Maryland (Fact Sheet No. 2021–3025), Fact Sheet; United States Geological Survey (USGS): Reston, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Ellicott City Historic Rain and Flash Flood—30 July 2016. National Weather Service; 2016. Available online: https://www.weather.gov/lwx/EllicottCityFlood2016 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Solomon, L. A Year after the Flood, Ellicott City Residents Reflect on Recovery and Community; Baltimore Sun: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. More Than 60 Displaced from Homes after Ellicott City Flood; Baltimore Sun: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Floods. National Weather Service; 2021. Available online: https://www.weather.gov/pbz/floods (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Fullilove, M.T. Psychiatric implications of displacement: Contributions from the psychology of place. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohl, C.A.; Tapsell, S. Flooding and human health. BMJ 2000, 321, 1167–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan, Y.-F.T. A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values, Morning Side Ed.; Columbia UP: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4684-8753-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Defining Place. In Place: A Short Introduction; Blackwell Ltd.: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, A.; Grek-Martin, J. “Now We Understand What Community Really Means”: Reconceptualizing the Role of Sense of Place in the Disaster Recovery Process. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Lin, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, D. Interaction between Risk Perception and Sense of Place in Disaster-Prone Mountain Areas: A Case Study in China’s Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Nat. Hazards 2017, 85, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P. Effects of Sense of Place on Responses to Environmental Impacts: A Study among Residents in Svalbard in the Norwegian High Arctic. Appl. Geogr. 1998, 18, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlikatti, S.; Maghelal, P.; Agnimitra, N.; Chatterjee, V. Should I stay or should I go? Mitigation strategies for flash flooding in India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.; Balogh, R.; Morbey, H.; Araoz, G. Health and social impacts of a flood disaster: Responding to needs and implications for practice. Disasters 2010, 34, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamlee-Wright, E.; Storr, V.H. “There’s No Place like New Orleans”: Sense of Place and Community Recovery in the Ninth Ward after Hurricane Katrina. J. Urban Aff. 2009, 31, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convery, I.; Bailey, C. After the flood: The health and social consequences of the 2005 Carlisle flood event. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2008, 1, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, I.; Garvin, S.; Lawson, N.; Richards, J.; Tippett, J.; White, I. Urban pluvial flooding: A qualitative case study of cause, effect and nonstructural mitigation. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2010, 3, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pross Keene, E. Phenomenological study of the North Dakota flood experience and its impact on survivors’ health. International J. Trauma Nurs. 1998, 4, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsell, S.M.; Tunstall, S.M. “I wish I’d never heard of Banbury”: The relationship between ‘place’ and the health impacts from flooding. Health Place 2008, 14, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Historical Flood Risk and Costs. 2021. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/data-visualization/historical-flood-risk-and-costs (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Noji, E.K. Natural disasters. Crit. Care Clin. 1991, 7, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.; Morbey, H.; Balogh, R.; Araoz, G. Flooded homes, broken bonds, the meaning of home, psychological processes and their impact on psychological health in a disaster. Health Place 2009, 15, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Climate Change. US EPA; 2013. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/climate-change (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Ellicott City CDP, Maryland. 2019. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/ellicottcitycdpmaryland (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Howard County Executive Calvin Ball. Ellicott City “Safe and Sound” Plan: Flood Mitigation Options; Howard County Executive Calvin Ball: Ellicott City, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. MD IMAP Ellicott City Floodplains and Flood Zones; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, K.; Desai, M.U.; Pelupessy, D.C.; Bell, M.L. Mental wellbeing following landslides and residential displacement in Indonesia. SSM-Ment. Health 2021, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Determining Sample Size. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Phenomenological Research Methods. In Existential-Phenomenological Perspectives in Psychology: Exploring the Breadth of Human Experience; Valle, R.S., Halling, S., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josselson, R. Interviewing for Qualitative Inquiry: A Relational Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush, R.; Sales, J.M.; Goldberg, A.; Bahrick, L.; Parker, J. Weathering the storm: Children’s long-term recall of Hurricane Andrew. Memory 2004, 12, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, F.J.; Charmaz, K.; McMullen, L.M.; Josselson, R.; Anderson, R.; McSpadden, E. Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis: Phenomenological Psychology, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquiry; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seebauer, S.; Winkler, C. Should I stay or should I go? Factors in household decisions for or against relocation from a flood risk area. Glob. Chang. 2020, 60, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Planning and Zoning. Ellicott City Watershed Master Plan; Department of Planning and Zoning: Howard County, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- King, D.; Bird, D.; Haynes, K.; Boon, H.; Cottrell, A.; Millar, J.; Okada, T.; Box, P.; Keogh, D.; Thomas, M. Voluntary relocation as an adaptation strategy to extreme weather events. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 8, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, K.; Turner, L.R.; Tong, S. Assessment of the Health Impacts of the 2011 Summer Floods in Brisbane. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2013, 7, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, C.; Latour, S.; Trudel, M.; Fortin, M. Post-traumatic stress disorder. After the flood in Saguenay. Can. Fam. Physician 2000, 46, 2420–2427. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, K.; Ikeda, K.; Kagi, N.; Yanagi, U.; Hasegawa, K.; Osawa, H. Effects of water-damaged homes after flooding: Health status of the residents and the environmental risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2014, 24, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, B.; Bryant, C.; Gilson, K.-M.; Koh, J.; Gibson, P.; Komiti, A.; Jackson, H.; Judd, F. A prospective study of the impact of floods on the mental and physical health of older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 17, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltais, D.; Lachance, L.; Fortin, M.; Lalande, G.; Robichaud, S.; Fortin, C.; Simard, A. Psychological and physical health of the July 1996 disaster victims: A comparative study between victims and non-victims. Sante mentale au Quebec 2000, 25, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillen, C.; North, C.; Mosley, M.; Smith, E. Untangling the psychiatric comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder in a sample of flood survivors. Compr. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wind, T.R.; Joshi, P.C.; Kleber, R.J.; Komproe, I.H. The impact of recurrent disasters on mental health: A study on seasonal floods in northern India. Prehospital. Disaster Med. 2013, 28, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H.; Smiley, S.L.; Blair, T.; Beutler, S.; Bowers, N.; Cadet, E. Coping with Floods in Pikine, Senegal: An Exploration of Household Impacts and Prevention Efforts. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Hunt, L.M.; Haider, W. Urban Flood Problems in Dhaka, Bangladesh: Slum Residents’ Choices for Relocation to Flood-Free Areas. Environ. Manag. 2007, 40, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Total | 19 |

| Experienced Both Floods | 16 |

| Relocated/no longer works in Ellicott City after 2016 flood | 4 |

| Relocated/no longer works in Ellicott City after 2018 flood | 2 |

| Worked AND lived in Ellicott City during flood(s) | 5 |

| Lived in Ellicott City flood zone during flood(s) | 16 |

| 14 |

| 2 |

| Worked in Ellicott City flood zone during floods(s) | 8 |

| 4 |

| 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chan, A.Y.; Burrows, K.; Bell, M.L. Why They Stayed and Why They Left—A Case Study from Ellicott City, MD after Flash Flooding. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710636

Chan AY, Burrows K, Bell ML. Why They Stayed and Why They Left—A Case Study from Ellicott City, MD after Flash Flooding. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710636

Chicago/Turabian StyleChan, Alisha Yee, Kate Burrows, and Michelle L. Bell. 2022. "Why They Stayed and Why They Left—A Case Study from Ellicott City, MD after Flash Flooding" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710636

APA StyleChan, A. Y., Burrows, K., & Bell, M. L. (2022). Why They Stayed and Why They Left—A Case Study from Ellicott City, MD after Flash Flooding. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710636