1. Introduction

Islamic insurance or

takaful is a growing subsector of the Islamic finance industry. Although not as vibrant as the Sukuk and Islamic banking markets, the

takaful industry has consistently enjoyed a double-digit growth (

World Takaful Report 2016). An important feature which distinguishes Islamic insurance from conventional insurance is the structure of its operational business model. A conventional insurance company owns the business and assumes risks from policyholders against a premium. An Islamic insurance company, referred to as

takaful operator (TO), on the other hand, underwrites risks on behalf of the policyholders. A TO technically works for the policyholders and manages the operation of the business against a variety of financial incentives. Unlike conventional insurance, policyholders under

takaful own the premium pool and insure one another by contributing to the pool. A conventional insurance operator owns all profits and losses of the insurance operation, whereas an Islamic insurance operator only receives compensation from policyholders, and all profits and losses legally belong to the policyholders. The relationship between the policyholders and a TO is, therefore, that of a principal and an agent.

A major problem with the principal–agent relationship is that the principal is unable to observe the true effort exerted by the agent leading to the well-known

moral hazard problem: a situation where the agent might not work in the best interest of the principal. This has attracted a great deal of interest in solutions which could mitigate the agency problem. One of the most celebrated solutions is to design incentive schemes and contracts which align the best interest of the principal and agent, in the tradition of

Holmstrom (

1979) and

Holmstrom and Milgrom (

1987). The process involves choosing optimal incentives from a set of feasible or available alternatives.

Islamic insurance operators receive a variety of compensations including (i) a

wakalah fee, where the

takaful operator receives a fixed proportion of the premium as an agency fee; (ii) a

mudarabah share, where the operator invests the premium pool and receives a share in the profit; and (iii) performance fee or a share in insurance surplus

1. Most TOs use a hybrid of these incentive schemes. Although similar in nature, the principal–agent relationship in the context of

takaful operation is unique in the sense that the nature of the competing compensation schemes is quite different from that traditionally considered in a typical model of optimal incentives. This motivated interest in an optimal incentive scheme for

takaful operators. There are only two papers which look at this relationship in the context of Islamic Insurance operations. A pioneering theoretical paper by

Khan (

2015a) studies the impact of competing incentives schemes on the performance of TOs and concludes that the TOs should be offered a share in the insurance surplus as well as some

wakalah fee. A

mudarabah hybrid should be offered only when effort exerted by the operator in investing the premium is more rewarding than effort exerted by the operator in underwriting risks.

Khan’s (

2015b) empirical analysis provides support to the conclusion of

Khan (

2015a) and shows that offering a

mudarabah hybrid is counter-productive.

According to the

World Takaful Report (

2016), the issue of the optimal structure of a

takaful model is a challenge and unsettled so far.

Khan (

2015a,

2015b) analysis is too academic and technical in nature, which does not readily appeal to regulators. Moreover, the standard framework makes some simplifying assumptions for model tractability, which makes it difficult for regulators to appreciate its value. This paper translates the abstract scientific knowledge accumulated in the optimal contracting literature into a simple analytical framework, which provides a novel and broader nontechnical perspective on optimal incentives in general, and on the optimal structure for

takaful operation in particular. The analysis in this paper is theoretical in nature. Given that the main objective of the paper is to identify incentive schemes which could be used to induce the TO to work in the best interest of the policyholders, the paper identifies different aspects of the best interest of the policyholders in the context of

takaful operation and discusses as to what extent does each of the competing operating models induce the TO to work in the best interest of the policyholders. The framework is used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each operational model, and how each of the competing operational models address the

moral hazard (lack of incentives to induce the agent to work in the best interest of the principal) and

adverse selection (lack of incentives to induce the TO to correctly price risks) problems associated with the nature of the

takaful operation; and how to use these incentives to protect infant

takaful operators. This will hopefully serve as a guide to motivate sound regulations and converge the

takaful model to the optimal structure identified through the analytical process used in this paper.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature by presenting the standard model used to study the principal–agent problem and highlights the different dimensions in which this relationship is studied in the literature.

Section 3 introduces the operational environment in which an Islamic insurance company operates.

Section 4 justifies as to why we need an optimal structure in the context of Islamic insurance, followed by an overview of the alternative

takaful models in vogue in

Section 5. These two sections provide a context for our analysis in

Section 6.

Section 6 pins down details of the analytical framework for comparing the efficiency of alternative models of

takaful operation in terms of their ability to align the best interest of the policyholders with that of the TO; uses the analytical framework to identify the optimal business incentives structure for

takaful operation and the supporting environment to reduce over-pricing; and discusses the relevance and implication of

Akerlof’s (

1982)

gift-exchange and how the

wakalah fee could address the

adverse selection problem.

Section 6 also discusses as to how the

wakalah fee could be utilized to protect infant

takaful operators and used as a tool to encourage entry into the

takaful industry.

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

This section presents a standard principal–agent model of optimal incentives, which serves as a point of reference in the relevant literature on optimal contracting. Suppose a principal hires an agent to produce certain output “

z”. The output is directly related to effort “

e” in a noisy environment, i.e.,

where

ε~N(0,

σ2) is the noise term, which means that the agent’s effort and type (

θz) is private information and the principal cannot observe his effort. The agent exerts the unobservable effort, but the actual output is determined by the noise. Both the agent and the principal, therefore, observe the output “

z”, but the principal cannot ascertain whether a particular outcome is due to effort exerted by the agent or a result of the noise in the environment.

The effort exerted by the agent is costly, and the cost function is assumed to be increasing with an increasing rate, i.e.,

c’ > 0 and

c’’ > 0 where

The agent will, therefore, be reluctant to exert effort unless it is in his best interest. This creates the well-known

moral hazard problem. The incentives offered to the agent are directly related to his productivity, captured by the production function

f(

θz,

e), and cost-efficiency, captured by the cost function,

c(

θc,

e). The agent may also consider hiding his true type, tricking the principal into hiring a relatively poor performing agent at a higher wage

2. This is referred to as the

adverse selection problem.

The principal mitigates these problems by offering a wage profile,

w(

z), such that it aligns the best interest of the agent with that of his own interest. The literature derives the optimal contract and chooses incentive parameters such that it maximizes the best interest of both parties. The most popular wage profile is linear in output, i.e.,

The linear contract assumes that the agent receives a lump-sum wage “a” and a share in output “b”. The principal reveals the wage profile; the agent is assumed to maximize his utility by choosing the effort level “e”. The principal maximizes his utility by choosing the incentive parameters “a” and “b”, taking into account the response of the agent.

Let

πi(

z) be the payoffs of

i (=P or A), and

Ui(

πi) be the corresponding utilities from these payoffs. The utility function is defined as

v(.) is concave and twice differentiable, increasing function taking a constant absolute risk aversion (CARA) form

where

ϕi quantifies

i’s degree of risk aversion, and

F(

x,

e) is the distribution of

x for a given

e. In a standard model,

and

, but other extended models modify these definitions to capture a variety of behavioral dynamics such as trust, reciprocity, fairness, and norms.

The agent chooses effort to maximize his utility

UA. The optimal level of effort is, therefore, given below

Given that the optimal effort “

e*” depends on the incentives parameters, “

a” and “

b”, the principal can induce the agent to work in his best interest by choosing the incentive parameters such that it maximizes his utility while leaving the agent at least as better off as his outside option (

UA >

U0 referred to as the participation constraint), i.e.,

3. Operational Environment

Before introducing a framework for analyzing different business models of takaful operation, it is useful to provide a brief overview of the environment an Islamic Insurance company operates in, which is as follows. A group of potential policyholders is interested in insuring each other. They, however, do not have any formal mechanism to coordinate with each other. A TO takes the initiative to bring these policyholders together. An Islamic insurance company is, therefore, a company formed by shareholders with interest in managing the takaful pool against financial incentives. It initiates the business on behalf of the to be policyholders and nominates itself as an operator. The TO admits members to the policyholders’ group; charges each policyholder a premium commensurate with the level of risk through a standard underwriting process. The premium pool, however, is not owned by the operator. It is legally the property of the policyholders as a group. Policyholders have the right to claim compensation in cases where the insured loss materializes. The TO receives certain compensation for managing the insurance operation. As stated earlier, the compensation scheme could either be wakalah, mudarabah, surplus-sharing, or a hybrid of the three.

Some of the critical questions that the literature tries to answer, apart from issues related to shari’ah compliance, are as follows.

A TO incurs a cost when initiating the takaful operation. What is the status of this capital? Is it a sunk cost, a donation, or a loan that is to be recovered from insurance surpluses over time?

The TO practically hires himself to work for policyholders. The policyholders are yet to be recruited by the TO. Who then decides as to what compensation should the TO receive? What is the optimal incentive structure which aligns the best interest of all stakeholders?

If the policyholders technically own the insurance surplus or profit, what happens if there is a deficit due to high claims? How should that deficit be financed?

If the takaful operation generates a surplus, who should receive the surplus and how is it distributed? Is it to be retained to mitigate future risks; distributed back to participants; or shared with the operator? Who decides as to how much should go to each category?

These questions, along with standard aspects of business viability, are frequently debated by academics and taken into consideration when regulators issue operational guidelines and regulations related to the takaful business. This paper mainly focuses on the second question.

4. The Need for an Optimal Structure

We previously stated that the relationship between policyholders and a TO is that of a principal and an agent. As is well known, the most important concern about this type of relationship is that the agent may not work in the best interest of the principal, typically referred to as the moral hazard problem. In practice, there are two popular ways to mitigate the moral hazard problem: (i) designing incentive schemes which induce the agent to work in the best interest of the principal, and (ii) regulations and proper monitoring which take care of the best interest of all stakeholders.

In general, the TO’s compensation scheme is primarily determined by board of directors of the Islamic Insurance company but may need to be approved by shariah supervisory board and the country’s regulatory authority as well. Given that policyholders do not have any representation in deciding the compensation awarded to the TOs on their behalf, regulators have the additional responsibility of designing regulations which prevent the TOs from serving their best interest at the expense of the policyholders. It is in this context that some regulatory regimes have started issuing guidelines or mandatory regulations around compensation for

takaful operators. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), for example, directed operators to use

surplus-sharing incentives only and remove any hybrids (

Khan 2015a). The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions’ (

AAOIFI 2017) Shariah Standard on

takaful, however, bars

takaful operators from receiving any share in the insurance surplus and recommends the use of the

wakalah–

mudarabah hybrid. Malaysia, on the other hand, allows a variety of incentive schemes. It is not clear as to why each country has adopted a different standard with regards to the business model. This paper provides a framework to rationalize the process and provides a simple framework of analysis to judge the competing incentive schemes.

5. Competing Structures for Takaful Operation

The TO’s compensation package could take serval forms. The three most popular compensation schemes were identified earlier:

wakalah,

mudarabah, and

surplus-sharing.

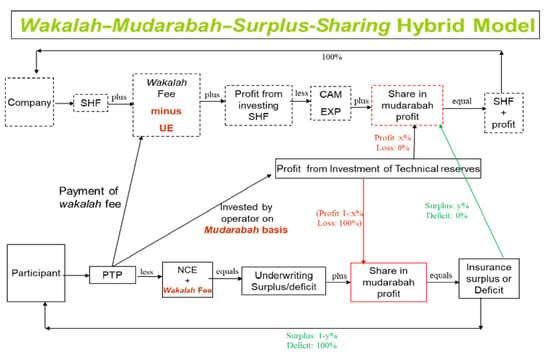

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 depict the different simple and hybrid models in vogue. The upper portion of each figure provides the financial flows of the shareholders of the insurance company, whereas the bottom portion of the figure provides financial flows of the policyholders. Shareholders of the company put together funds, which are invested and earn a profit. The company also incurs some expenses, referred to as CAM EXP (Company’s Admiration and Management Expenses). Deducting these expenses and adding any net income received from managing the

takaful operations determines the profit of the insurance company. The flow and nature of income received from

takaful operation differ across different models, which we will discuss shortly.

Takaful operators charge each policyholder or participant a certain amount of premium, which goes into the participant takaful pool (PTP). In the absence of reinsurance, PTP represents gross written or earned premium. With reinsurance, the pool is simply the net written or earned premium. The takaful operational expenses can be broadly categorized under two heads; NCE (Net claim expenses) and Underwriting Expenses (UE). All claims are paid from the PTP. The Net Claim Expenses (NCE, net of reinsurance claim) are, therefore, deducted from the PTP in all models. UE are expenses incurred in selecting, classifying, and pricing risks which are paid by the policyholders, except under the standard wakalah arrangement, where the TO bears these expenses. With this in mind, let us now briefly outline the structure of each operational model of takaful

Pure Mudarabah Model: The TO underwrites risks in this case on a no-profit and no-loss (NPNL herein) basis, but invests technical reserves in the PTP on a

mudarabah basis. As in

Figure 1, the TO receives a pre-agreed percentage, x, from any profit generated by the investment of technical reserve (PFIITR). The remaining, (100 − x)% goes to the policyholders’ fund. The policyholders, however, bear the entire loss in cases where the profit is negative. The insurance profit or loss (IP) in this case is given by

The mudarabah model can also be seen as a musharakah (partnership) model when the operator jointly invests the technical reserves and shareholders fund (SHF). The profit and losses, in this case, are shared according to the rules of a standard musharakah contract.

Pure Wakalah Model: The TO, in this case, receives an agency fee, expressed as a percentage of the premium. The fee is received upfront at the time policyholders are admitted to the pool. The NCE, in this case, are paid by the policyholders, whereas the UE are paid by the operator. The TO invests the premium pool as part of the

wakalah arrangement as a

wakeel (an agent) of the policyholders, as shown in

Figure 2. The TO, therefore, does not receive a share in the investment income from the technical reserve (PFIITR).

The

wakalah arrangement in practice requires the TO bear the UE. This is, however, not a binding requirement of the

wakalah contract. These expenses could be borne by the policyholders as well. The

wakalah fee, in this case, would naturally be relatively lower. Also, the

wakalah fee could be a lump sum amount as well, which is similar to an

ijarah contract (hiring someone on lump-sum wages). We will include these two options in our technical analysis and show that these alternative options are inferior to the

wakalah structure depicted in

Figure 2.

Surplus-Sharing Model: Just like the

mudarabah model, the TO, in this case, manages the

takaful operation on an NPNL basis. The operator, instead of receiving a share in the PFIITR, receives a share, y, in the insurance surplus as a reward for performance. All expenses, the NCE as well as the UE, are paid by the policyholders. Insurance profit, in this case, is IP = PTP − NCE + PFIITR: y% of which is received by the TO and (100 − y)% belong to policyholders. The entire loss, however, is borne by policyholders in case of a loss. This is depicted in

Figure 3.

Wakalah–Mudarabah Hybrid Model: This model combines the

mudarabah arrangement in

Figure 1 with the

wakalah arrangement in

Figure 2. See

Figure 4. The TO underwrites risks as a

wakeel (agent) of the policyholders and invests the premium pool on a

mudarabah basis. As a

wakeel, the TO receives a

wakalah fee and bears the UE, whereas, as a

mudarib (investment manager), the TO receives a share in the investment income from technical reserves. The insurance profit or loss (IP) in this case is given by

Wakalah–Surplus-Sharing Hybrid Model: This model combines the

wakalah model in

Figure 2 with the

surplus-sharing model in

Figure 3. As shown in

Figure 5, the TO underwrites risks and invests technical reserves as a

wakeel and receives a share in the insurance surplus as a reward for underwriting performance. The NCE are paid from the PTP, whereas the TO bears the UE. The insurance profit or loss is given by IP = PTP −

wakalah fee − NCE + PFIITR, which is shared with the TO according to the agreed proportions.

Wakalah–Mudarabah–Surplus-Sharing Hybrid Model: The TO in this model underwrites risks as a

wakeel; invests technical reserves as

mudarib; and receives a share in the insurance surplus as a reward for careful underwriting (See

Figure 6). Policyholders bear the NCE, whereas, the TO bears the UE. Both share the

mudarabah profit and insurance surplus according to the agreed proportions.

6. Analytical Framework

Having discussed the basic structure and simple accounting framework that underlies each business structure, we are now ready to discuss the effectiveness of each model and identify the optimal business structure which aligns the best interest of policyholders and shareholders of the insurance company. The key to judging the optimality of an incentive scheme is to understand whether or not the incentive scheme induces the agent, TO in our case, to work in the best interest of the principal, policyholders in our case. Given our accounting framework, the best interest of the policyholders is served when the NCE and the UE are minimized and the investment income from technical reserves (IITR) and Insurance Profit (IP) are maximized. Moreover, their best interest also requires that they are charged the right premium. Thus, any incentive scheme which induces the TO to (a) minimize the NCE, (b) minimize the UE, (c) maximize the IITR (d) maximize the IP, and (e) charge the right, actuarially fair, premium.

Table 1 reports whether or not each of the principal contracts underlying the different business models serves the best interest of the policyholders. The table reports the three popular contracts used in

takaful operation, listed earlier, as well as the

Ijarah contract and a variation of the

wakalah contract, as discussed in the previous section.

The ijarah contract simply pays the TO a lump sum salary. All expenses are paid from the premium pool, which is owned by the policyholders. The TO does not receive any share in the investment income from technical reserves and insurance profit. The TO, therefore, does not have any incentive to minimize the NCE and UE or maximize the IITR and the IP. Moreover, he does not have any incentive to charge an actuarially fair premium and may be inclined to over-price. This is a textbook example of the most inefficient incentive scheme in the context of takaful operation. This perspective perhaps explains as to why this model is not adopted by any takaful operator in practice.

In the mudarabah model, the TO underwrites risks on a NPNL basis and receives a share in the IITR. The TOs, therefore, only have an interest in maximizing the IITR. They, however, do not have any interest in minimizing the NCE and the UE and may be inclined to over-price risks to maximize the premium pool. This may come at the cost of poor underwriting. In the wakalah model where the TO receives a wakalah fee and bears the UE, the operator has interest in minimizing the UE only. In the theoretical variation of the wakalah model where the TO does not bear the UE, labeled as wakalah2, the TO does not have any interest in serving the best interest of policyholders and is as inefficient as in the ijarah model. In case of the surplus-sharing model, the TO receives a share in the insurance surplus which creates interest in maximizing the IP. This, by duality, also creates interest in minimizing the UE and NCE and maximizing IITR, as they help maximize the IP.

6.1. Optimal Business Structure for Takaful Operation

In light of the above discussion, it is obvious to conclude that the surplus-sharing model is the most efficient business structure for takaful operation, whereas ijarah is the most inefficient model. A wakalah hybrid might be more efficient if the wakalah fee is optimally chosen. We expect that a dollar received as wakalah fee provides better incentives in terms of motivating an underwriting effort than a dollar received as a reward for performance. This is because wakalah fee, expressed as a percentage of the premium charged to policyholders, is received upfront, whereas the insurance surplus is contingent on performance. A risk-averse TO can, therefore, be motivated to exert greater effort with the right combination of wakalah and surplus-sharing.

A

mudarabah hybrid may or may not add value. To see this, notice that both the return on the effort exerted in investing technical reserves and the return on the effort exerted in overall underwriting in terms of a share in the insurance surplus are uncertain. They are substitutes in the sense that sharing of the IITR reduces the insurance surplus and the dollar value of the surplus received by the TO and policyholders, and vice versa. Thus, it is more efficient to have a

mudarabah hybrid if the

mudarabah profit is more likely to realize than an insurance surplus, and vice versa. Whereas both these outcomes are uncertain, the TO has relatively better prospects to control the insurance surplus than the

mudarabah profit. This is because insurance surplus can be affected by appropriate adjustments in the premium charged to policyholders, minimizing underwriting expenses, and quality underwriting, resulting in better claim management, whereas the IITR depends on the market outcome and expertise of the fund manager. A

mudarabah hybrid is, therefore, more likely to be inefficient, and a

wakalah–

surplus-sharing model might work best. The above is consistent with predictions of the theoretical model presented by

Khan (

2015a) and empirical results in

Khan (

2015b).

6.2. Addressing the Over-Pricing Issue

Risks pricing is actuarially fair if the premiums charged are equal to the expected value of the compensation received against expected losses. A common problem in all of the above operational models is that they all tend to over-price risks, except the

ijarah model

3. The TO may charge more than the actuarially fair premium as this guarantees a higher

wakalah fee in the

wakalah model; a bigger premium pool for investment and a higher profit in dollar terms in the

mudarabah model; and a greater insurance surplus and the dollar amount received by the TO in the

surplus-sharing model. Let us use a stylized example to show how insurance companies manage to charge a higher than the actuarially fair price to policyholders.

Consider an individual who faces a fixed loss of L dollars with probability q. An insurance company offers the individual a policy which promises to bear the entire loss against a premium of P dollars. The expected loss of the policyholder is, therefore, qL, which is the actuarially fair premium the insurer should charge to the policyholder. Thus, an insurance company should collect information related to the probability distribution and associated distribution of insured losses. Insurance companies, however, collect more than that. For example, they tend to collect information about income of the policyholders and additional information to get insight into their degree of risk aversion. This type of information helps with an over-pricing decision.

To see this, let us assume the utility function of the policyholder is

U =

Xa, where

X is the payoff of policyholders, and

a < 1 quantifies a policyholder’s degree of risk aversion. The closer the value to 0, the more risk-averse the individual is. Let

W be the wealth or income of the policyholder. A policyholder who buys the insurance policy will end up having a payoff of

(W −

P), giving her a utility of

(W −

P)a. Similarly, a policyholder who does not buy the insurance policy will end up with either a payoff of

(W −

L) with probability

q in case the loss materializes or

W in case it does not, with probability 1 −

q. The corresponding utilities, in these cases, would be

(W −

L)a and

Wa, respectively. The decision tree in

Figure 7 depicts this information below.

Thus, if a participant purchases the policy, she will have a payoff of

(W −

P)a with certainty, and if she doesn’t, her expected utility will be

q(W −

L)a + (1 −

q)Wa. The expected utility theory tells us that a policyholder will purchase the insurance policy so long as the premium is such that certain utility is at least as much as the expected utility, i.e., Certain Utility = Expected Utility, which means

It is interesting to note that the decision to buy an insurance policy depends upon the probability of loss “q”, the size of the insured loss “L”, the degree of risk aversion “a”, and wealth “W”. Recall that an actuarially fair price depends on “q” and “L” only. This inequality always holds when the policyholder is charged an actuarially fair premium. A risk-averse individual will, therefore, always purchase an actuarially fair insurance policy. Actuarially fair pricing essentially means that the TO must assume that the policyholders are risk neutral, whereas, in reality, they are risk-averse.

Given that a risk-averse individual is willing to pay a higher than the actuarially fair price for the same expected loss, insurance companies, therefore, have the potential to charge a higher premium due to risk aversion. The higher the degree of risk aversion, the greater is the potential to charge a relatively higher premium. Similarly, a relatively low-income client is more concerned about her loss and is more likely to pay, and be charged, a higher premium.

There are mainly two ways to overcome this issue. First, insurance companies should be allowed to collect information related to the expected loss only, i.e., the probabilities and distribution of insured losses. Information such as the degree of risk aversion and income of the prospective policyholders should not be collected unless they are demonstrated to reveal credible information about the expected loss. Given that risk aversion is universal, it is not possible to stop the insurance companies from capitalizing on risk aversion. A more credible solution to resolve the over-pricing issue would be to promote competition among insurance companies. The competition allows insurance companies to compete on price as well as the quality of services delivered, which helps converge the premium to its actuarially fair value and at the same time facilitate a better-quality claim and benefits experience.

6.3. Adverse Selection, Wakalah Fee, and Akerlof’s Gift-Exchange

One of the TO’s main jobs is to underwrite risks, which involves selecting, classifying, and pricing risks. The

wakalah fee is an upfront agency fee received by the TO which is typically a certain percentage of the premium. Whereas this motivates the TO to exert effort in increasing the size of the pool by admitting more policyholders, it does not provide any incentive to make sure the policyholder is appropriately classified in the right risk category and priced accordingly. This increases the risk of misclassification, which leads to

adverse selection. The adverse selection means that the NCE will be higher, which increases the

risk of ruin (the risk that the insurance company will not be able to meet its claims). This argument, however, assumes that individuals respond to

explicit incentives only

4. A plethora of research on

Akerlof’s (

1982)

gift-exchange5, however, shows that they respond to

implicit incentives such as the

wakalah fee. The

gift-exchange hypothesis, first proposed in

Akerlof (

1982), postulates that workers reciprocate the “gift” of above market base-wage with above minimum effort, even though the effort is costly. This behavioral aspect goes against the predictions of standard models of optimal contracting which postulate that people respond to

explicit incentives only. This motivated, and continues to do so, a large number of interesting laboratory and field experiments with a variety of applications, as well as the development of theoretical models to explain the

gift-exchange anomaly

6. What this means in terms of the

takaful operation is that, if the

gift-exchange postulate is valid, the

wakalah fee would motivate the TO to take interest in carefully underwriting risks and minimizing the

adverse selection problem.

Khan (

2015b) tested this hypothesis in the context of Islamic Insurance and found evidence in favor of the

gift-exchange hypothesis. In particular,

Khan (

2015b) finds that there is a U-shaped relationship between

loss ratio (net claim expenses as a percentage of net premium

7) and

wakalah fee which is a direct evidence of the

gift-exchange from the

takaful industry. This an important result which discounts concerns related to

wakalah fee, encouraging poor underwriting and

adverse selection.

6.4. Incentives for Infant Takaful Operators

Given that Islamic insurance is a relatively new industry which is gradually growing over time, every year new operators join in the industry. A good number of operators in the takaful industry can, therefore, be classified as infant takaful operators. This aspect of the industry, therefore, needs special attention. Consistent with the infant industry argument, nascent takaful operators do not have as much underwriting experience as their older competitors. They are, therefore, more likely to misprice and adversely select risks than their experienced competitors. This means that getting an insurance surplus during early stages is relatively difficult. Thus, in order to encourage new operators to join in and existing ones to survive, they need some protection. This protection can be internalized in the incentive schemes. The wakalah fee could balance some of the risk associated with surplus-sharing. Infant takaful operators should, therefore, be paid a relatively higher wakalah fee as compared with the experienced operators with reduced exposure to the surplus-sharing part. These incentives should, however, converge to a standard wakalah–surplus-sharing arrangement as they get experienced over time.

7. Summary and Conclusions

Islamic insurance is a growing sector of the Islamic finance industry. As opposed to conventional insurance companies, A

takaful operator, TO, technically works for policyholders against certain financial compensation. In practice, the compensation offered to a TO is determined by a hybrid of (i) an agency contract known as

wakalah (where the operator receives a fixed upfront fee expressed as a percentage of premiums collected from the policyholders); (ii) a profit-sharing contract known as

mudarabah (where the operator invests the premium pool and receives a share in the profit without sharing losses); and (iii) a

surplus-sharing contract, where the operator receives a share in the insurance surplus and nothing in case of deficit. Even though the TO works for the policyholders, they do not have any say in deciding the compensation scheme. Regulators are therefore keen to regulate the compensation schemes to align the best interest of the policyholders with those of the shareholders of the insurance company. There is, however, lack of guidance as to which compensation scheme to choose from, as pointed out in the

World Takaful Report (

2016). This paper fills this gap, building up on the scientific knowledge accumulated in the optimal contracting literature, develops a nontechnical analytical framework in the context of takaful operation, and shows as to how it can be used to analyze competing operational models of Islamic insurance. The process involves identifying the best interest of policyholders and exploring as to what extent does each of the incentives schemes induce the agent to work in the best interest of the policyholders. An application of the analytical framework to competing

takaful models shows that the

wakalah–

surplus-sharing hybrid is the most efficient operational model in terms of aligning the best interest of policyholders and

takaful operators.

Khan (

2015a) did a survey of incentives offered to TOs and showed that more than 50% of the incentive schemes do not offer

surplus-sharing.

Wakalah–

mudarabah is the most popular incentive scheme offered to TOs in Bahrain, Pakistan, Qatar, and the UAE.

Surplus-sharing, on the other hand, is used in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, and used as a hybrid with

wakalah in some cases in Malaysia. This points towards the possibility that, from an optimal contracting point of view, there is room for improvement in the incentive schemes offered around the world.

This paper also argues that all of the competing incentive schemes encourage the TOs to charge more than the actuarially fair premium and suggests a line of action which could be used to converge the market to charge an actuarially fair premium. It argues that this could be achieved by banning the takaful operators from collecting any information other than those directly related to quantify the expected loss and promoting competition.

The paper also discusses a concern that the wakalah contract might encourage poor underwriting, resulting in adverse selection of risks during the underwriting process. Empirical evidence, however, points towards the existence of gift-exchange in the takaful industry, which discounts such concerns and encourages the use of wakalah as an attractive hybrid.

Finally, given that the takaful industry is still growing and many takaful operators could be classified as infant takaful operators, they might not be as experienced in underwriting risks as their older competitors. They are therefore more likely to misprice and adversely select risk, as compared with their experienced competitors. This reduces the attractiveness of the surplus-sharing incentives, as a surplus is relatively less likely to occur in the case of adverse selection. Just like the infant industry argument, they need some protection. Their risk could be reduced by offering a relatively higher wakalah fee and reducing exposure to the surplus-sharing part.