Defining Self-Management for Solid Organ Transplantation Recipients: A Mixed Method Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. The Approach of This Study

1.1.2. Self-Management and SM Attributes

1.1.3. SOTx Patients and Rationale for Augmented Definition of SM

1.1.4. A Brief Historical Context for SM and Chronic Illness Research

1.2. Study Rationale

1.3. Study Objectives and Research Questions

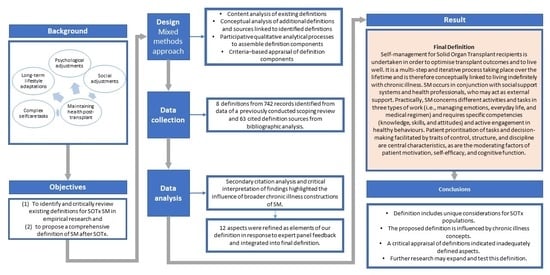

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of an Approach

2.2. Definitions Currently in Use—Study Identification via Secondary Analysis of SMART Scoping Study Dataset

2.3. Definitions Currently in Use–Selection of Sources of Evidence and Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Definitions Currently in Use—Data Extraction

- Verbatim definitions of SM;

- Verbatim citations within definitions and definitions within the original source(s);

- Bibliographic elements were extracted from cited sources: population context and concept [40];

- Solid organ type(s);

- References to behavioural or sociological theory were recorded.

2.5. Bibliographic Analysis of Identified Definitions—Study Identification

2.6. Data Charting

2.7. Data Analysis

Section Critical Appraisal

2.8. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Content Analysis of Definitions

3.3. Conceptual Analysis via Bibliographic Searching

3.4. SOTx SM Attributes (Cluster Headings)

3.5. Conceptual and Contextual Analysis of Definitions and Cited Sources

3.6. Critique of the Adequacy of Definitions Identified

3.7. Creation of an Integrated Comprehensive Definition

3.8. Final Definition for SM for SOTx Patients

3.9. Summary of Conceptual Attributes

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnston, B.; Rogerson, L.; Macijauskiene, J.; Blaževičienė, A.; Cholewka, P. An exploration of self-management support in the context of palliative nursing: A modified concept analysis. BMC Nurs. 2014, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudin, J.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Girard, A.; Houle, J.; Ellefsen, É.; Hudon, C. Integrated self-management support provided by primary care nurses to persons with chronic diseases and common mental disorders: A scoping review. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Been-Dahmen, J. Self-Management Support. Ph.D. Thesis, Erasmus University Roterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ettenger, R.; Albrecht, R.; Alloway, R.; Belen, O.; Cavaillé-Coll, M.W.; Chisholm-Burns, M.A.; Dew, M.A.; Fitzsimmons, W.E.; Nickerson, P.; Thompson, G.; et al. Meeting report: FDA public meeting on patient-focused drug development and medication adherence in solid organ transplant patients. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dew, M.A.; Myaskovsky, L.; Steel, J.L.; DiMartini, A.F. Post-transplant Psychosocial and Mental Health Care of the Renal Recipient. In Psychosocial Care of End-Stage Organ Disease and Transplant Patients; Sher, Y., Maldonado, J.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- DiMartini, A.F.; Golden, E.; Matz, A.; Dew, M.A.; Crone, C. Post-transplant Psychosocial and Mental Health Care of the Liver Recipient. In Psychosocial Care of End-Stage Organ Disease and Transplant Patients; Sher, Y., Maldonado, J.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Abtahi, H.; Safdari, R.; Gholamzadeh, M. Pragmatic solutions to enhance self-management skills in solid organ transplant patients: Systematic review and thematic analysis. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Egidio, V.; Mannocci, A.; Sestili, C.; Cocchiara, R.; Cimmuto, A.; La Torre, G. Return to work after kidney transplant: A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada, J.; Crone, C. Post-transplant Psychosocial and Mental Health Care of Pancreas and Visceral Transplant Recipients. In Psychosocial Care of End-Stage Organ Disease and Transplant Patients; Sher, Y., Maldonado, J.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, P.A.; Pereira, L.F.; Taylor, K.E.; Wiener, I. Post-transplant Psychosocial and Mental Health Care of the Cardiac Recipient. In Psychosocial Care of End-Stage Organ Disease and Transplant Patients; Sher, Y., Maldonado, J.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 237–344. [Google Scholar]

- Sher, Y. Post-transplant Psychosocial and Mental Health Care of the Lung Recipient. In Psychosocial Care of End-Stage Organ Disease and Transplant Patients; Sher, Y., Maldonado, J.R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte, L.M.; Powell, H. Preventive Health in the Adult Solid Organ Transplant Recipient. In Primary Care of the Solid Organ Transplant Recipient; Wong, C.J., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 275–300. [Google Scholar]

- De Geest, S.; Dobbels, F.; Gordon, E.; De Simone, P. Chronic Illness Management as an In-novative Pathway for Enhancing Long-Term Survival in Transplantation. Am. J. Trans-Plant. 2011, 11, 2262–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Been-Dahmen, J.M.J.; Grijpma, J.W.; Ista, E.; Dwarswaard, J.; Maasdam, L.; Weimar, W.; Van Staa, A.; Massey, E.K. Self-management challenges and support needs among kidney transplant recipients: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 2393–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, U.; Haaland-Øverby, M.; Fredriksen, K.; Westermann, K.F.; Kvisvik, T. A scoping review of the literature on benefits and challenges of participating in patient education programs aimed at promoting self-management for people living with chronic illness. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klewitz, F.; Nöhre, M.; Bauer-Hohmann, M.; Tegtbur, U.; Schiffer, L.; Pape, L.; de Zwaan, M. Information Needs of Patients About Immunosuppressive Medication in a German Kidney Transplant Sample: Prevalence and Correlates. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urstad, K.H.; Wahl, A.K.; Moum, T.; Engebretsen, E.; Andersen, M.H. Renal recipients’ knowledge and self-efficacy during first year after implementing an evidence based educational intervention as routine care at the transplantation clinic. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, C.; Dunsmore, V.; Murphy, F.; Rolfe, C.; Trevitt, R. Long-term care and nursing management of a patient who is the recipient of a renal transplant. J. Ren. Care 2012, 38, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzer, K.; Sterneck, M.; Welker, M.-W.; Nadalin, S.; Kirchner, G.; Braun, F.; Malessa, C.; Herber, A.; Pratschke, J.; Weiss, K.H.; et al. Current Challenges in the Post-Transplant Care of Liver Transplant Recipients in Germany. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988; Volume XVIII, 358p, ISBN 1-55542-082-6. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Managing Chronic Illness at Home: Three Lines of Work. Qual. Sociol. 1985, 8, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L. Chronic Illness and the Quality of Life, 1st ed.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bratzke, L.C.; Muehrer, R.J.; Kehl, K.A.; Lee, K.S.; Ward, E.C.; Kwekkeboom, K.L. Self-management priority setting and decision-making in adults with multimorbidity: A narrative review of literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K. Self-Management of Chronic Illness: A Model for the Future. Gener. J. Am. Soc. Aging 1993, 17, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K.; Holman, H. Self-Management Education: History, Definition, Outcomes, and Mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, J.; Wright, C.; Sheasby, J.; Turner, A.; Hainsworth, J. Self-Management Approaches for People with Chronic Conditions: A Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.; Schoo, A. Supporting Self-Management of Chronic Health Conditions: Common Approaches. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, P.M.; Kendall, S.; Brooks, F. Nurses’ responses to expert patients: The rhetoric and reality of self-management in long-term conditions: A grounded theory study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2006, 43, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audulv, Å. The over time development of chronic illness self-management patterns: A longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Lorig, K.; Holman, H.; Grumbach, K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002, 288, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, J. How to use education as an intervention in osteoarthritis. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2001, 15, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.-C.; Chen, H.-M.; Huang, C.-M.; Hsieh, P.-L.; Wang, S.-S.; Chen, C.-M. The Difficulties and Needs of Organ Trans-plant Recipients during Postoperative Care at Home: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, A.A.; Shea, K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2011, 43, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, A.; Whitehead, L. Evolution of the concept of self-care and implications for nurses: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.; Barclay, L.; Schmied, V. Defining Social Support in Context: A Necessary Step in Improving Research, Intervention, and Practice. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 942–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobst, S.; Stadelmaier, J.; Zöller, P.; Grummich, K.; Schmucker, C.; Wünsch, A.; Kugler, C.; Rebafka, A. Self-management in adults after solid-organ transplantation: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e064347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 5th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-215688-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, G.; Greenhalgh, T.; Westhorp, G.; Buckingham, J.; Pawson, R. RAMESES Publication Standards: Meta-Narrative Reviews. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Fetters, M.D.; Ivankova, N.V. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patzer, R.E.; Serper, M.; Reese, P.P.; Przytula, K.; Koval, R.; Ladner, D.P.; Levitsky, J.M.; Abecassis, M.M.; Wolf, M.S. Medication understanding, non-adherence, and clinical outcomes among adult kidney transplant recipients. Clin. Transplant. 2016, 30, 1294–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Bader, M.; Beltran, K.; Dojlidko, D. Improving Transplant Discharge Education Using a Structured Teaching Approach. Prog. Transplant. 2011, 21, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvindt, M.; Nozohoor, S.; Kisch, A.; Lennerling, A.; Forsberg, A. Symptom Occurrence and Distress after Heart Transplantation-A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Demir, I. Effects of Illness Perception on Self-Care Agency and Hopelessness Levels in Liver Transplant Patients: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 31, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.; Bratzke, L.C. Cognitive Function in Liver Transplant Recipients Who Survived More Than 6 Months. Prog. Transplant. 2020, 30, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demian, M.N.; Thornton, A.E.; Shapiro, R.J.; Loken Thornton, W. Negative affect and self-agency’s association with immunosuppressant adherence in organ transplant: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2021, 40, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almgren, M.; Lundqvist, P.; Lennerling, A.; Forsberg, A. Self-efficacy, recovery and psychological wellbeing one to five years after heart transplantation: A Swedish cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021, 20, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadami, A.; Memarian, R.; Mohamadi, E.; Abdoli, S. Patients’ experiences from their received education about the process of kidney transplant: A qualitative study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2012, 17 (Suppl. S1), S157–S164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Astin, F.; José Closs, S. Guest Editorial: Chronic Disease Management and Self-Care Support for People Living with Long-Term Conditions: Is the Nursing Workforce Prepared? J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action/Albert Bandura: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; Volume XIII, 617p, ISBN 0-13-815614-X. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, J.H.; Turner, A.P.; Wright, C.C. A Randomized Controlled Study of the Arthritis Self-Management Programme in the UK. Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, J.H.; Williams, B.; Wright, C.C. ‘Instilling the Strength to Fight the Pain and Get on with Life’: Learning to Become an Arthritis Self-Manager through an Adult Education Programme. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, S.H.; Burlingame, G.M.; Nebeker, R.S.; Anderson, E. Meta-Analysis of Medical Self-Help Groups. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2000, 50, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateson, G. Mind and Nature a Necessary Unity; Collins: Glasgow, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, M. Chronic Illness as Biographical Disruption. Sociol. Health Illn. 1982, 4, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, E.A.; Steiner, J.F.; Fernald, D.H.; Crane, L.A.; Main, D.S. Descriptions of Barriers to Self-Care by Persons with Comorbid Chronic Diseases. Ann. Fam. Med. 2003, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, B. Complications and Comorbidities. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2007, 107, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.M.; Becker, M.H.; Janz, N.K.; Lorig, K.; Rakowski, W.; Anderson, L. Self-Management of Chronic Disease by Older Adults: A Review and Questions for Research. J. Aging Health 1991, 3, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. A Nursing Model for Chronic Illness Management Based upon the Trajectory Framework. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 1991, 5, 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Creer, T.L.; Renne, C.M.; Christian, W.P. Behavioral Contributions to Rehabilitation and Childhood Asthma. Rehabil. Lit. 1976, 37, 226–232,247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. Self Care—A Real Choice Self Care Support—A Practical Option; Department of Health: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fishwick, D.; D’Souza, W.; Beasley, R. The Asthma Self-Management Plan System of Care: What Does It Mean, How Is It Done, Does It Work, What Models Are Available, What Do Patients Want and Who Needs It? Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 32, S21–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzmaurice, D.A.; Machin, S.J. Recommendations for Patients Undertaking Self Management of Oral Anticoagulation. BMJ 2001, 323, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantz, S.B. Self-Care: Perspectives from Six Disciplines. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 1990, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gately, C.; Rogers, A.; Sanders, C. Re-Thinking the Relationship between Long-Term Condition Self-Management Education and the Utilisation of Health Services. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gül, A.; Üstündağ, H.; Zengin, N.; Üniversitesi, İ.; Sağlık, B.; Okulu, Y. Böbrek Nakli Yapılan Hastalarda Öz-Bakım Gücünün Değerlendirilmesi. J. Gen. Med. Genel Tıp Derg. 2010, 20, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, K.; Corrigan, J.M. (Eds.) The 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities: Report of a Summit; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, K.; Corrigan, J.M. (Eds.) Priority Areas for National Action: Transforming Health Care Quality; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; ISBN 0-309-08543-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jerant, A.F.; von Friederichs-Fitzwater, M.M.; Moore, M. Patients’ Perceived Barriers to Active Self-Management of Chronic Conditions. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 57, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, E.; Ehrlich, C.; Sunderland, N.; Muenchberger, H.; Rushton, C. Self-Managing versus Self-Management: Reinvigorating the Socio-Political Dimensions of Self-Management. Chronic Illn. 2011, 7, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.; Muehrer, R.J.; Bratzke, L.C. Self-Management in Liver Transplant Recipients: A Narrative Review. Prog. Transplant. 2018, 28, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, D.; Koch, T.; Price, K.; Howard, N. Chronic Illness Self-Management: Taking Action to Create Order. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krein, S.L.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D.; Makki, F.; Kerr, E.A. The Effect of Chronic Pain on Diabetes Patients’ Self-Management. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, S. How and Why the Motivation and Skill to Self-Manage Chronic Disease Are Socially Unequal. Res. Sociol. Health Care 2008, 26, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S. Prioritizing Illness: Lessons in Self-Managing Multiple Chronic Diseases. Can. J. Sociol. 2009, 34, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Holman, H.; Sobel, D.; Laurent, D.; Gonzalez, V.; Minor, M. Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions: Self-Management of Heart Disease, Arthritis, Stroke, Diabetes, Asthma, Bronchitis, Emphysema and Others, 2nd ed.; Bull: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K. Chronic Disease Self-Management: A Model for Tertiary Prevention. Am. Behav. Sci. 1996, 39, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Holman, H. Arthritis Self-Management Studies: A Twelve-Year Review. Health Educ. Q. 1993, 20, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.; Chastain, R.L.; Ung, E.; Shoor, S.; Holman, H.R. Development and Evaluation of a Scale to Measure Perceived Self-Efficacy in People with Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989, 32, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.; González, V.M.; Laurent, D.D.; Morgan, L.; Laris, B.A. Arthritis Self-Management Program Variations: Three Studies. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 11, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.; Lubeck, D.; Kraines, R.G.; Seleznick, M.; Holman, H.R. Outcomes of Self-Help Education for Patients with Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1985, 28, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; Sanders, C.; Kennedy, A.P.; Rogers, A. Shifting Priorities in Multimorbidity: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study of Patient’s Prioritization of Multiple Conditions. Chronic Illn. 2011, 7, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Committee, Ministry of Health. Meeting the Needs of People with Chronic Conditions; National Health Committee, Ministry of Health: Wellington, NZ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, L.; De Souza, L.H.; Ide, L. A Delphi Study of Self-Care in a Community Population of People with Multiple Sclerosis. Clin. Rehabil. 2000, 14, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Palen, J.; Klein, J.J.; Seydel, E.R. Are High Generalised and Asthma-Specific Self-Efficacy Predictive of Adequate Self-Management Behaviour among Adult Asthma Patients? Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 32, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, V.; Cossette, S.; Frasure-Smith, N.; Heppell, S.; Guertin, M.-C. The Efficacy of a Motivational Nursing Intervention Based on the Stages of Change on Self-Care in Heart Failure Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 25, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, M.R. Self-Management in Adults with Asthma. Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, B.L. The Shifting Perspectives Model of Chronic Illness. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2001, 33, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasauskas, R.; Spoo, L. Literally Improving Patient Outcomes. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2006, 18, 270–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, B.K. Patient Adherence or Patient Self-Management in Transplantation: An Ethical Analysis. Prog. Transplant. 2009, 19, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, B.K. Patient Self-Management of Chronic Disease: The Health Care Provider’s Challenge, 1st ed.; Jones & Bartlett: Massachusetts, UK, 2004; ISBN 0-7637-2307-X. [Google Scholar]

- Redman, B.K. Responsibility for Control; Ethics of Patient Preparation for Self-Management of Chronic Disease. Bioethics 2007, 21, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.; Poole, H. Chronic Pain and Coping: A Proposed Role for Nurses and Nursing Models. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 34, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Dickson, V.V. A Situation-Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-Care. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 23, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer-Keller, P.; Dickenmann, M.; Berry, D.L.; Steiger, J.; Bock, A.; De Geest, S. Computerized Patient Education in Kidney Transplantation: Testing the Content Validity and Usability of the Organ Transplant Information System (OTIS). Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecher, V.J.; DeVellis, B.M.; Becker, M.H.; Rosenstock, I.M. The Role of Self-Efficacy in Achieving Health Behavior Change. Health Educ. Q. 1986, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S.; Paterson, B.; Russell, C. The Structure of Everyday Self-Care Decision Making in Chronic Illness. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 1337–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, W.R.; Buelow, J.M. Hybrid Concept Analysis of Self-Management in Adults Newly Diagnosed with Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009, 14, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstündağ, H. Renal Transplantasyon Uygulanan Hastanın Taburculuk Eğitimi. Nefroloji Hemşireliği Derg. 2006, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Von Korff, M. Organizing Care for Patients with Chronic Illness. Milbank Q. 1996, 74, 511–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worth, H. Self Management in COPD: One Step Beyond? Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 32, S105–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, T.; Jenkin, P.; Kralik, D. Chronic illness self-management: Locating the “self”. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 48, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M. The Corbin and Strauss Chronic Illness Trajectory Model: An Update. Sch. Inq. Nurs. Pract. 1998, 12, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

| Included Publications’ Author, Year of Publication, Title | Methodology | Summary of Study Methods and Results | Definition Extract within Included Publication | Defining Attributes (Conceptual Component Codes) from 8 Definitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almgren et al., 2021 [50] Self-efficacy, recovery and psychological wellbeing one to five years after heart transplantation: a Swedish cross-sectional study | Cross sectional Obs (Quant) | Methods: cross sectional study with 79 HTx; instrument: German version of the self-efficacy for managing chronic disease 6-item scale (SES6G). Results: level of self-efficacy was high, fully/partly recovered HTX; overall good wellbeing in population. Discussion: self-efficacy is about balancing expectations; self-efficacy is a mediator for self-management | The success of transplantation partly rests on the self-management ability of the heart transplant recipient (HTR), in conjunction with family and transplant professionals to manage symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes and psychosocial, cultural and spiritual consequences. After HTx self-management is mainly constituted by the ability and process that the HTR uses in conscious attempts to gain control of his or her everyday life with a new heart rather than being controlled by it [33].” “Self-management focuses on the activities people carry out in order to create structure, discipline and control in their lives [50].” (p. 35) | In conjunction with family and transplant professionals > To manage symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes, and psychosocial, cultural and spiritual consequences > Is mainly constituted by the ability and process > To gain control of his or her everyday > Focuses on the activities to create structure, discipline, and control in their lives |

| Demian et al., 2021 [49] Negative affect and self-agency’s association with immunosuppressant adherence in organ transplant | Systematic review—meta-analysis | Methods: meta-analysis. Results: 50 studies included, increased NA is associated with worse adherence, high self-agency associated with good adherence. Discussion: different adherence measurement methods applied in the studies; cultural effect on association | “Living with a transplant requires a high degree of self-management, defined as ‘the tasks [one] must undertake to live well with one or more chronic conditions’ (Adams et al., 2004, p. 57) [70] and includes adherence to the medication regimen” (p. 90) | The tasks [one] must undertake > To live well > Includes adherence to the medication regimen |

| Demir and Demir, 2021 [47] Effects of illness perception on self-care agency and hopelessness levels in liver transplant patients: a descriptive cross-sectional study | Descriptive /exploratory/ obs(quant) | Methods: descriptive cross-sectional method, “Patient Identification Form (PIF)”, the “Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ)”, the “Self-Care Agency Scale (SCAS)”, and the “Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS). Results: 120 Ltx correlation between BHS and B-IPQ, mean hopelessness scale scores. Discussion: high negative illness perception, mean sores of self-efficacy, no correlation between self-efficacy and illness perception→but LTx feeling stronger; participation in care | “After the transplant, it is necessary to increase the self-care ability of the patient to take an active role in protecting, improving, and raising their own health, to continue their daily life activities, and to ensure transition to normal life as soon as possible (Gül et al., 2010)” (p. 474) | Increase the self-care ability > To take an active role in protecting, improving, and raising their own health > Continue their daily life activities > Ensure transition to normal life as soon as possible |

| Dalvindt et al., 2020 [46] Symptom occurrence and distress after heart transplantation: a nationwide cross-sectional cohort study | Descriptive/exploratory/ observational (quant) | Methods: wellbeing instruments→Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB), Organ Transplant Symptom and Well-being Instrument (OTSWI). Results: 79 HTx; most common symptoms: trembling hands, decreased libido; sociodemographic factors, more symptoms when not working; with poor psychological wellbeing, living alone, depended on follow up. Discussion: fatigue is strongest predictor | “Self-management has been adopted by transplant professionals as a framework for efficient support to transplant recipients in managing their chronic condition, namely the transplantation” (p. 2) | A framework for efficient support > Managing their chronic condition |

| Ko and Bratzke, 2020 [48] Cognitive function in liver transplant recipients who survived more than 6 months | Secondary data analysis (quant) | Methods: secondary data analysis with Monreals Cognitive Assessment, and Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ), and the Basel Assessment of Adherence with Immunosuppressive Medication Scale (BAASIS). Results: 107 Ltx; More than half of the recipients had global cognitive impairment. Age was associated with significant differences in global cognitive function. Discussion: SM and cognitive function are somehow related | “Liver transplant recipients ability to self-manage, which for this study is defined as ‘an iterative process of priority setting and decision making for the practical management of an illness’ is likely influenced by cognitive function, especially memory and executive function [74]” (p. 1) | An iterative process > Priority setting > Decision-making > Practical management of an illness > Cognitive function, especially memory and executive function |

| Patzer et al., 2016 [44] Medication understanding, non-adherence, and clinical outcomes among adult kidney transplant recipients | Descriptive/exploratory/ observational (quant) | Methods: in-person interviews about medication knowledge, regimen use, medication adherence. Results: 99KTx high percentage (35%) of non-adherence to immunosuppressive medication. Discussion: higher number of medications, lower health literacy level, longer time after Tx leads to medication non-adherence | “Medication self-management for transplant recipients is a multistep process by which organ transplant recipients take their medication. The patient must first fill the prescription, and then, the patient should be able to correctly name, identify, and understand the medication. The third step is organization of multiple medications into the appropriate dosing frequency. Next, actually taking the medication at the correct dosage is essential. For those who are on complex or multiple medications, monitoring medication changes is essential. Finally, patients must sustain medication behaviors indefinitely to achieve medication self-management” (p. 1295) | Multi-step process > Monitoring medication changes is essential |

| Ghadami et al., 2012 [51] Patients’ experiences from their received education about the process of kidney transplant: a qualitative study | Qualitative | Methods: qualitative study with content analysis approach with 18 participants. Results: need for educational experiences at the beginning and end of transplantation; personal struggle to increase awareness to reach self-management and transplanted kidney preservation. Discussion: demand for efficient education to achieve the level of decision-making and problem-solving; demand for encouragement | “Renal transplant recipient self-management can be divided into the same components as used for other chronic illness populations: (1) management of the medical regimen, (2) management of the emotions and (3) management of the new life roles [20]. Since KT patients need support in fields of knowledge, skills and motivations, [99] they should acquire awareness, skills and attitudes as well as adequate resources to attain healthy behaviours in order to feel responsible” (p. 158) | Can be divided into the same components as used for other chronic illness populations > Management of the medical regimen > management of emotions > Management of the new life roles > Need support in fields of knowledge, skills, and motivations > Acquire awareness, skills, and attitudes > To attain healthy behaviours in order to feel responsible |

| Frank-Bader et al., 2011 [45] Improving transplant discharge education using a structured teaching approach | Best/clinical practice article | Methods: development of standardised teaching process to Ktx/LTx, strategies to encourage patient and families. Results: patient and nurses’ satisfaction with teaching process. Discussion: structured learning process helped to minimise the amount of information at one time | “Redman (2009) [94] has posited that self-management is also essential for transplant patients because, although transplantation itself is an acute intervention, living with the transplant is a chronic condition. Therefore, patients must have the self-efficacy and knowledge and skills to manage their own care over a lifetime” (p. 332) | >Essential > Acute intervention > Chronic condition > Must have self-efficacy > Must have knowledge < Must have skills > Over lifetime |

| Reference and Year of Publication | SOTx Population Focus in Cited Sources? | Missing Aspects not Present in Our Identified Definitions Found in Level 1 Secondary Sources | Deviations in Summary | Theoretical Basis Identified in 8 Definitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almgren (2021) [50] | No | 1 Richard and Shea 2011 [33] 2 Kralik 2004 [75] Richard and Shea 2011 [33], Wilkinson and Whitehead (2009) [34]—second generation cited source, who also included community in the collaborative aspect of SM | Richard and Shea 2011 [33] is citing another (original) source: Thorne 2003 [101] | None |

| Demian (2021) [49] | No | Demian et al. 2021 [49] omit dimensions of definitions from [69,74] Adams 2004 [70] reference—including self-management support (which includes SM education) | None identified | (Adams et al., 2003) [71] Self-management support: the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions by health care staff to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems, including regular assessment of progress and problems, goal setting, and problem-solving support |

| Demir and Demir (2021) [47] | Yes | 1 No full translation available for Gül 2010 [69] Üstündağ (2006) [103] (a second generation cited source—no full text available) | None identified | Self-care ([69] renal transplantation discharge education), concepts: the patient to protect and improve their own health, to take an active role in upgrading, daily life self-care, to maintain their activities, to increase the ability to live a normal life as soon as possible |

| Dalvindt et al. [46] | N/a | Authors composed their own definition | Not applicable | None |

| Ko and Bratzke 2020 [48] | No | Ko 2018 [74] Source cited in Ko et al. 2018 is Bratzke et al. 2015 [23] with Lindsay 2009; Morris et al. 2011 [78,86] | None identified | Self-management—iterative process, ongoing process, prioritising care based on changing needs and conditions |

| Patzer (2016) [44] | N/a | Authors composed their own definition | Not applicable | None |

| Ghadami (2012) [51] | 1 No 2 Yes 3 No | 1 Corbin JM, Strauss 1988 [21] 2 Schäfer-Keller et al. 2009 [99] Concept missing from summary: “It is impossible not to manage one’s health. The only question is how one manages.” Self-management is a lifetime task. From Lorig and Holman (2003) p. 1 [24] Schaffer-Keller (2009) summarise important aspects of the cited model (from Corbin and Strauss 1988): (i) kidney transplant recipient self-management includes managing a medical regimen, emotions, and (new) life roles; (ii) SOTx may affect the patient’s family and/or community and should significantly influence interaction with healthcare professionals; (iii) this may begin pre-transplantation; (iv) specific aspects assuming varying levels of importance at each stage; (v) core skills [10,13] deemed reasonable for kidney recipients to have or acquire p. 111 3 Prasauskas and Spoo 2006 [93] Home health care management practice and delivery of information to improve patient outcomes | 3 Prasauskas and Spoo, 2006 [93] cited, however, this does not accurately summarise elements in the publication: use a teach-back technique for addressing home care for the elderly if managing their own care. The paper emphasises responsibility of a clinician and delivery of information. -This paper is about health literacy, not self-management -Likely the associated source is Schäfer-Keller 2009 [99], who talk about control | Corbin JM, Strauss 1988 [21], patient education |

| Frank-Bader (2011) [45] | Yes | Redman 2009 [96] Inherent symptom management, physical and psychosocial consequences (defined by Barlow (2002) [27] within citation) are absent | Barlow (2002) [26], definition within Redman (2009) [94] not cited | None |

| Population | SOTX | C/I | Gen. | C/I | Single | Non-C/I | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOTx | SOTx—kidney | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| Source level 1 | ● | ●● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||||||

| Source level 2 | ●●●●● | ●●● | ●●●●● | ●● | ●●● | ● | |||||||||||

| Source level 3 | ●●●●●●●●●● | ● | ● | ● | ●● | ●● | ●● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Source level 4 | ●● | ●● | ●● | ● | ● |

| Definition Component | [50] | [46] | [49] | [47] | [51] | [45] | [48] | [44] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defines population | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Defines conceptual/theoretical approach | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Defines settings of SM | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Isolates key concepts | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Defines key concepts | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | |

| Indicates relative importance of concepts | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ○ | ● |

| Explains relationship between concepts (process) | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ● |

| Linkages to patient behaviours | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Contextualised temporally | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● |

| Defines various relevant persons/perspectives | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| Inclusion of HCP perspective | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Provides an explanation of possible interventions | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ |

| Defines measurable outcomes | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Inclusion of or reference to defining elements endorsed by patient or HCP group | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Relevancy for our study to create a definition for the entire SOTX population for all SM tasks | ○ Heart transplant recipient | ● | ● | ● | ○ Renal transplant recipient | ● | ○ Liver transplant recipients (from first 6 months) | ○ (Medication only) |

| Attribute in Our Working Definition of SM for SOTx | Type of Population Attribute | Associated Attribute within SM General Population [2] |

|---|---|---|

| To optimise transplant outcomes | SOTx population only | - |

| Active engagement in healthy behaviours | SOTx population only | - |

| Patient prioritisation of tasks and decision-making facilitated by traits | SOTx population only | - |

| Control, structure, and discipline are central characteristics | SOTx population only | - |

| Moderating factors of patient motivation, self-efficacy, and cognitive function | SOTx population only | - |

| Medical regimen | SOTx population only | - |

| It is a multi-step and iterative process | Attributable to SOTx and possibly SM general population | |

| Requires specific competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) | Attributable to SOTx and possibly SM general population | Information about condition and/or its management Training/rehearsal for psychological strategies, |

| Taking place over the lifetime and is therefore conceptually linked to living indefinitely with chronic illness | Attributable to general SM population | |

| SM occurs in conjunction with social support systems and health professionals | Attributable to general SM population | Social support and lifestyle advice and support Provision of/agreement on specific clinical action plans, regular clinical review |

| SM concerns different activities and tasks in three types of work (i.e., managing emotions, everyday life, and medical regimen) | Attributable to general SM population | Training/rehearsal for practical self-management activities Monitoring of condition with feedback, practical support with adherence—medication or behavioural Provision of equipment, training/rehearsal for everyday activities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brunner, K.; Weisschuh, L.; Jobst, S.; Kugler, C.; Rebafka, A. Defining Self-Management for Solid Organ Transplantation Recipients: A Mixed Method Study. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 961-987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020073

Brunner K, Weisschuh L, Jobst S, Kugler C, Rebafka A. Defining Self-Management for Solid Organ Transplantation Recipients: A Mixed Method Study. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(2):961-987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020073

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrunner, Katie, Lydia Weisschuh, Stefan Jobst, Christiane Kugler, and Anne Rebafka. 2024. "Defining Self-Management for Solid Organ Transplantation Recipients: A Mixed Method Study" Nursing Reports 14, no. 2: 961-987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020073

APA StyleBrunner, K., Weisschuh, L., Jobst, S., Kugler, C., & Rebafka, A. (2024). Defining Self-Management for Solid Organ Transplantation Recipients: A Mixed Method Study. Nursing Reports, 14(2), 961-987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020073