1. Introduction

An observed, regularity of certain magnitudes by people in their ordinary life is a basic motive for calculation inquiry, which invites measurement system and shapes human behavior. The computation capacities have been casting a light on the measurement advancement of economics and other disciplines in human history [

1]. Recently, it is quite challenging to make economic decisions (production, trade condition, and functional aspect of products) without reliable specification, quality, and quantity measurement. Measurement behavior forms a significant portion of the economies in China and African countries, as it can, therefore, contribute towards major continental priorities, such as boosting intra-Africa trade and investments. It is also an effective approach to deal with projects associated with modern agricultural development in sub-Saharan Africa [

2]. Previous study revealed that human capital and know-how are needed for any agricultural development [

3]. Moreover, some factors, such as long-standing practices in Africa and China, also contribute to measurement behavior disparities.

A thirty-five days’ training (from April 2016 to May 2016) in a rural area of China (Guangshui) exposed a significant difference between Chinese and African measurement behaviors. The conventional tools and methods, such as cup, bulk, or heaps are the major means of measurement to exchange agricultural product in many African countries. In South Africa, for instance, during the 17th century, the measurement system was somewhat confusing, because there was no accurate standard of reference [

4]. Additionally, in Ethiopia, numerous units of measurement have been used in history, but until now the values of most of those units are not well defined [

5]. Moreover, Abebe et al. [

6] in their study in Oromia region in Ethiopia, identified multiplicity and non-uniformity of local measures, the anomalies of conversion conventions of local units, ownership and choice decisions of appropriate units, the two-hand palm cereals gift, the different home, and marketplace quantity measurements, and the buyers’ unethical conducts proved the existence of measurement disparities hence the unreliability of such measurements.

Similarly, in Cote d’Ivoire, the measurement system practice has been taking a long time to develop. According to Legge [

7], Cote d’Ivoire started to use metric system since 1890. Conversely, the heterogeneous units of measurement are still vastly in use mainly in rural agricultural marketplace. In other words, the diffusion of metric units of measurement to the distant areas of the country was not effective almost for more than a century. For instance, nowadays, people employe heaps, cups, buckets measurement tools, and methods to conduct economic transactions. The inconsistency in such measurement units markedly complicates domestic exchange and intensifies the disintegration of the local market. Furthermore, the multiplicity and unreliability of measures create a significant cost of measurement, which also has an adverse consequence for macro-level economy.

Historically, in China, the development of measurement tools, such as “dù” to measure the length of an object, the “liàng”, an instrument to measure the volume of an object and also the “héng” an instrument to measure the weight of an object, and the commodities measurement system has undergone varied improvements. However, in search of a surviving society, China has tried to develop modern measurement tools to reduce transaction costs. In Qin dynasty, the unifier of China in 221 B.C. started “a system of weight and measure” to stabilize the country. The “big and small theory” was developed during Sui dynasty reunified China in A.D. 589, and subsequently, with the emergence of the “decimal” as a system of measurement during the tang and song dynasties [

8]. As early as the Qin Dynasty, China had achieved standardization of “weights and measures” across the country [

8,

9]. During the preliminary study of this research, a second measurement behavior observed in China was the use of “jin” (half a kilogram) quantity measurement system instead of one kilogram (kg) as a unit of measure. Despite the long history of measurement system evolution for economic trade, currently, the people of China are employing a homogenous measurement instrument across the country.

However, the important inquiry that needs to be answered here is why the various traditional units of measurement are yet to be used in the rural marketplace of Cote d’Ivoire? In contrast, what are the major explanations that made China capable of implementing and using the same standard unit across the country? A few researchers stated that mathematical capacities were key bases to the measurements [

1,

10,

11,

12]. Indeed, from this point, one can understand certainly that calculation capacity is not only the beginning for measurement and technology but also nurtures measurement behaviors. Universal measurement practices across different countries (rural marketplace of China and Cote d’Ivoire) are, therefore, existing because of the inconsistency of the computing power of people. However, the association between mathematics (computation) capacities and measurement system of economic trade remains an unchartered interest of research. In fact, investigating whether the mathematical computation and measurement have a connection and simultaneous effect on measurement technology adoption is discipline quo discipline, or second-order questions [

13]. Herein, the second-order question is not discipline-specific subject matter rather beyond a discipline issue.

It is against this backdrop that this study was conducted to examine the differences in the measurement behaviors of market participants in the context of the rural marketplace of China and Cote d’Ivoire. The calculation capacity of market traders in both countries’ rural marketplaces was also explored. Moreover, the correlation between the calculation capacities and measurement behavior was analyzed. The influence of measurement behavior and PCC upon institution, knowledge and cultural capital, technological cooperation, and economic development were examined. Overall, the study has practical and theoretical contributions. The study highlights the need for stakeholders to re-consider measurement issues in macro-policies, thereby trading parties could acquire potential benefits from agricultural trade. Furthermore, the study expands the knowledge economy and technology adoption issues in the context of China and Africa. So far, the mathematics spillover effect on the economic trade measurement system and behavior is limited. To this aspect, the study contributes to the existing theories of both disciplines of economics and mathematics. This paper is organized into introduction where a general view on the topic is extensively provided. The methods and sampling techniques used in data collection are described in the methodology section. The results and discussion present major findings of the study and are thoroughly discussed with respect to their theoretical and policy implications, while the conclusion summarizes the practical implications of these findings and recommendations for the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Areas

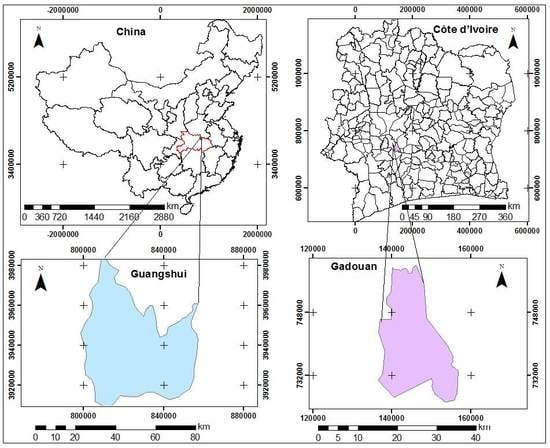

A comparative analysis of the measurement behaviors and computing power of rural people was made by selecting two rural towns from China and Cote d’Ivoire purposively. Four rural markets were selected in both China and Cote D’Ivoire. Chenxiang and Luodian rural markets were the two study zones chosen to conduct this study in China. Chenxiang town is under the jurisdiction of Guangshui city (northern part of Hubei province,

Figure 1), which is located 18 km south from Guangshui. Chenxiang has a total population of 52,751 and covers an area of 142 square kilometers. Luodian township is also under the jurisdiction of Guangshui city, located in the south-central part of Guangshui city, with an area of 109 square kilometers and a population of 46,799. In Cote d’Ivoire, the sub-prefecture of Gadouan was selected (

Figure 1). Gadouan is a town in west-central Cote d’Ivoire, a sub-prefecture of Daloa department in Haut-Sassandra region, Sassandra-Marahoué district. The town is located between the geographic coordinates of 6°39′ N 6°10′ W with a population of 57,470 [

14]. Additionally, Zaliohouan is a village in western Cote d’Ivoire and located in the sub-prefecture of Gadouan with latitude and longitude of 6°47′ N 6°14′ W.

2.2. Data Collection and Sampling Methods

A simple random sampling method was used to collect data from 167 rural people from the target population in China and Cote d’Ivoire (

Figure 2). Primary data was obtained by using a semi-structured questionnaire as a data collection tool. The socio-demographic/economic characteristics of the respondents are summarized as descriptive statistics. There was a total of 84 questionnaires (49 in Chenxiang town and 35 in Luodian township) rural markets in China (

Figure 2). In the case of Cote d’Ivoire, there was a total of 83 questionnaires with 54 in Gadouan town and 29 in Zaliohouan (

Figure 2). The difference in the size of the sample in the two study zones in each country is due to the differences in the township in both countries.

A primary survey conducted on food quality and its pricing was organized with traders in traditional markets. A pilot survey was organized in China and Cote d’Ivoire rural areas to validate the data collection instrument (semi-structured questionnaires). The pilot research allowed us to have an idea on the content of the questionnaire and the variables needed and more importantly, to identify the zones where this study could be conducted. In reality, asking a question about the calculation capacity of rural people is somewhat challenging because they tend to be reluctant about this kind of questionnaires. From a practical perspective, we opted for a small number of questions. The survey questionnaires included information on basic socio-economic characteristics of traders and some business information, such as occupation, experience in business, transaction type, market type, use of calculator, type of weighing and trading frequency, together with a detailed description based on a list of quality indicators. In rural markets, people usually sell agricultural products (grains, vegetables, fruits) and some daily consumption products (convenience shops). Traders that specialize in specific products and often sell only those products and traders selling similar products are usually clustered in the same area within the market. In these four chosen zones, it is usually an open market. Comparatively, 60% and 77.10% of rural traders practice the open market system in China and Cote d’Ivoire, respectively. The respondents included farmers, agricultural retailers, and wholesalers, mainly engaged in the trading of vegetable and melon, agricultural and side-line products, and a few were engaged in industrial retailing. In the Chenxiang and Luodian market, 100% of traders use traditional or current electronic balances to perform weighing transactions, which are priced in Chinese Yuan (RMB). The market value of products traded between 350 and 207,266 yuan ($50 to $30,000). In Cote D’Ivoire markets, the main products are essentially agricultural products including beef, vegetables, grains, and tubers and the traders consist of retailers, shopkeepers, and wholesalers of agricultural products. The total value of goods traded is between, 2000 West African CFA Franc (XOF) and 2,000,000 West African CFA franc (XOF) ($3.5 to $17,300).

2.3. The Peasants ‘Calculation Capacities (PCC) Measurement and Data Analyses

The measurement of computing power was mainly based on measuring the mental arithmetic ability without using any calculation tool. The questionnaires have been arranged from the less difficult to the most difficult one in such a way to save time. The difficulty level of the questions was determined during the pilot research study and reorganized in the final version of the questionnaire. The calculations were divided into three categories: One-digit multiplication, fractional multiplication, two-digit multiplication (

Table 1). Based on these three categories, the proportion of true responses provided by each peasant was determined. This proportion of true answers provided by each peasant was our PCC.

Does this mental arithmetic ability represent the computing power of the respondents? Indeed, we did not find a direct study that explains the association between mental arithmetic and the computing power of peasants. However, a few studies assumed that the individuals who are familiar with the operation of the numbers and who frequently perform calculations are inevitably strong in mental arithmetics [

1,

10,

11,

12]. This assumption is reasonable. We performed econometric analyses to identify factors that influence peasants’ computational capacity. The econometric analysis used the multiple regression model to predict the various correlates that have been studied. The multiple linear regression model was built based on the assumptions of least square method regarding linearity, normality, and homoscedasticity.

where:

Yi = calculation capacity of the peasant

i (dependent variable), and

Xi are the independents variables and

εi = Error term. Based on the literature [

15,

16], we summarized the explanatory variables (

Xi) of our model (

Table 2).

4. Theoretical Implications

Measurement is the backbone of science and technology as science and technology are the basics of every economic development. Meanwhile, measurement and science are to some extent related, and, therefore, having a weak measurement system in a country can highly impact the knowledge dissemination. Various comparative studies of mathematics abilities among inter-racial and intercultural subjects have been copiously reported in the United States and elsewhere [

27]. However, the direct comparison between measurement behavior and computational power in rural markets in China and Africa has not been seen in the existing literature. Our findings may have important theoretical implications in the following aspects:

4.1. Institutional Level Aspect

Most African rural traders seldom use weighing scales to measure agricultural products not necessarily because they cannot afford them, but because of the apparent lack of a socio-cultural orientation towards this as a habit and willingness to adapt. Habits are just like instincts. Changing a habit needs a lot of sacrifices and time. During the survey in Cote d’Ivoire, the authors asked one respondent who was selling chicken in Gadouan rural market. Why don’t you use a weighing balance to measure the chicken’s weights since the weights of chickens are not uniform? The participant replied that:

The balances are not beneficial to us. When we are selling by unit, it is much profitable. Can you see this chicken is completely white without any other colors? Thus, some consumers come to market looking for this special attribute to use it as a sacrifice or in other ritual ceremonies. In this kind of situation, we can significantly increase the price and gain more on the chickens. So, in this case, it is really difficult for us to use balance and we work based on market demand. When there are some ritual ceremonies, people will pay any price without arguing on it. You know we are in Africa, and we are still attached to our traditional believes and habits.

This justification was not so convincing since there is a possibility to set some specific prices for such an attribute. However, such traders think such situations were profitable for them as they arrogate the power to dictate products pricing to their benefit. Many unique product attributes, such as color, are just periodic, and represent only one-third of market demands. Therefore, setting a standardized price and using weighing balance can significantly reduce the transaction costs for the sellers and the consumers. The trading behavior of this chicken seller in Gadouan rural market is also a common practice even in some markets of Abidjan (economic capital of Cote d’Ivoire). Indicating that urbanization failed to eliminate this kind of practice in Cote d’Ivoire. Regulatory institutions are the surest bet to legislate and ensure strict compliance with such rules for a leap forward. Many attempts of weighing balance implementation in Cote d’Ivoire have failed probably due to the reasons above and more importantly, the attachment to the long-standing practices.

4.2. Cultural Capital and Knowledge Paradigm

The attachment to local traditions which conflicts with the development of science and technology partly explains the lack of modernization of most African countries. African and Chinese societies are not logic-based societies as they learned how to cope with contradictions compared to Western societies where everything seems logic-based. The Chinese society has a narrower gap between traditional and modern societies compared to African societies, partly attributable to socio-cultural diversity. The Shanxi, the Hui, and the Ningbo merchants in the old Shanghai were trained from the apprenticeship system. This shows Chinese culture and modern enterprise management became compatible with each other. Chinese culture attaches importance to the present world, the anxiety of survival, the importance attached to children, and the emphasis on practice-based education promotes capital accumulation and knowledge dissemination.

The paradigm of knowledge is also a common problem in China, as China relies on its agricultural economy, the path dependence of its related way of thinking and overemphasis on technology at the expense of science. Logical thinking, precision, and scientific theory have been underdeveloped in China [

8,

28]. Despite local empirical knowledge, it is not sufficient to produce modern science, but it helps them understand and imitate modern science and technology. The huge differences in history and cultural foundation will inevitably lead to differences in real development. The existing measurement disparities in Africa (Cote d’Ivoire) between long-standing practices and development of science exacerbate the stagnation of science and technology. African countries need to embrace modern science and integrate it with their traditions to make a move towards sustainable development. To this context, measurement and calculation, which are one of the basics of science and technology, will ease local transactions and rural commerce. Therefore, they are interesting variables towards the development of science and technology.

The measurements and calculations need skills and innovation, not just a copy and paste. Chinese have over the years been labelled as imitators. Chinese take their time to remove errors based on their own situation and reality before applying any model. Imitation is the advanced copying, in other words, to imitate is to copy intelligently. It is like the scanned version versus the original version of a document. African countries will benefit more by learning how to imitate instead of blindly copying a particular model. Chinese society learned how to imitate but not copy. Measurements of quality and calculation capacities of a population show the quality of a country in terms of human capital. Measurement is the basis of science and technology. That is why Africa needs to pay much attention to this problem. Improving the measurement system in Africa in general and particularly in Cote d’Ivoire will easily help the country to adapt to science and technology development. The attachment to long-standing traditional practices creates what we call path dependence which conflicts with the development of science and technology. Although East Asian society or more specifically Chinese society is traditionally an experience-skilled knowledge system, its high level of skill system contains high measurement and computational power, coupled with a strong impulse to the economic benefits behind technological advancement, technical foundation, and technology. Ultimately, Chinese society can quickly absorb the Western science and technology system by showing strong imitation [

29]. This interpretation is consistent with the perspective of cultural capital research of Bai Tao [

30].

4.3. China-Africa Technological Cooperation and Economic Development Level

China–Africa cooperation can start with practical technology, strengthen the interaction and cooperation between Chinese smallholder farmers and African smallholder farmers, and gradually improve measurement and calculation habits of African people. China is slightly ahead of Africa in measurements and calculations. This proximity effect can provide unique advantages for China–Africa cooperation. Many trading and production tools or methods and techniques traditionally used in China require high measurement accuracy and computational power. The introduction of these practical tools, techniques, and methods into Africa can gradually improve the ability of African peasants to calculate and predict. In terms of China–Africa cooperation, China first needs to train African human resources. This is not simply to train international students, technicians and government officials in Chinese or Western universities, but to face the vast majority of African workers (farmers). Key socio-demographic variables like gender and education were not statistically significant, and should be factored in selecting the trainees in agricultural technology transfer programs between China and Cote d’Ivoire or other African countries.

The concept of a developing country is unclear, a non-strict economic term. In the existing developing countries, there are significant differences with some having a long history of civilization, some with a relatively short history, and their economies revolving around collecting, fishing, and hunting. Each of these countries has its own distinctiveness. Some have a strong religious orientation and some are more secular. Some have experienced a long-term planned economy, and some have always been a free economy. These geo-cultural variables have an important impact on economic development. The economy is not only subject to the variables of the economic system but also subject to variables outside the economic system, especially historical, technical, and cultural variables. The same labor force, the same capital stock, have different meanings in different cultural contexts. The difference in measurement behaviors observed in Cote d’Ivoire and China, to some extent, explains the difference in their respective developmental stages. It is better to classify countries with different historical backgrounds, especially those with different economic and technological historical backgrounds, social and cultural variables that have a greater impact on the economy. For instance, studying developing countries with intensive farming, studying developing countries with primitive agriculture, and studying developing countries with strong religious backgrounds. In this way, a good economy strategy can be designed. The East Asian economic miracle is a major event in the second half of the 20th century and the 21st century of the world economy. Although many explanations are given in theory, there is not much attention paid to the quality of individual workers in the East Asian society. From the perspective of China’s development history, the Chinese labor force is certainly one of the key elements as exemplified by the tight relationship between measurement and computing power of its population and quality of labor. African countries should understand that the basic resource of any country is its population and the driving force is its working class.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed peasants’ measurement behaviors and computing powers in China (Chenxiang and Luodian rural marketplaces) and Cote d’Ivoire (Gadouan and Zaliohouan rural marketplaces). The study showed that the trading behaviors and calculation capacities were diverse between China and Cote d’Ivoire rural markets. The comparative results depicted that the traditional and modern balances were popular in China, whereas selling by heaps, cup/glass, pieces systems were practiced in Cote d’Ivoire among retailers and modern balance was popular only with large traders or wholesalers dealing bulk commodities, or traders with expensive products. In fact, the two sets of trading systems may be efficient in their respective societies, or as a result of rational choice.

Conversely, the calculation capacity of Chinese rural traders was found to be higher than that of Cote d’Ivoire rural traders. The PCC increases with trading behaviors, but to a certain extent in the two countries. Experience was found to be the most effective factor that influences the calculation capacity of Chinese and Ivorian rural traders. Rural marketplace measurement behaviors reflect the quality of the whole population’s attitude to dealing with numbers (digitalized world). Although the two options are rational under their respective socio-economic conditions, this does not mean that the difference between the two is not important. Moreover, the difference in computing power does not reflect racial differences but is the result of different social practices. Measurement behaviors on the rural market reflect the ability of people to deal with numbers, and this daily practice has a profound influence on increasing the quality of digital citizens. China’s high ability and habits in measurement and calculation make it relatively easy for Chinese society and even East Asian societies to receive modern Western technology.

Besides, the study sows a seed to explain the economic benefit of a reliable measurement system at a transactional level, by relating mathematics and economics disciplines together. The implication of PCC and measurement practices to institution, knowledge and cultural capital, and China–Africa technological cooperation were revealed in a way to contribute to the economic growth. Herein, the approach employed to measure the rural traders’ computing power needs further improvement, which will require developing a more accurate method to measure the PCC. However, future studies should investigate if there is a direct relationship between measurement accuracy and acceptance of modern science and technology.