1. Introduction

Fueled by the global K-beauty syndrome, Korea’s cosmetics industry [

1,

2,

3], the eighth largest in the world [

4], representing nearly 3.0% of the global market, in 2019 the revenue in the beauty and personal care market amounts was estimated to be

$11.3 billion and the market is expected to grow annually by 4.0% (CAGR 2019–2023) (see

Figure 1) [

5]. The market’s largest segment is skin care with a market volume of

$6.8 billion in 2019. In relation to the total population figures, per person revenues of

$220.63 are generated in 2019 (see

Figure 2). According to the data from the Korea National Statistical Office, in 2018, the annual online shopping transaction value of cosmetics was about KRW9.84 trillion, of which the mobile shopping transaction value was about KRW5.51 trillion (1000 KRW is approximately equal to 0.75 Euro and 0.83 USD) [

6].

Since the infant death scandal caused by a humidifier disinfectant in 2016 has been a shock to the Korean society, many harmful ingredients have been detected in various product groups and consumers are increasingly unable to trust the ingredients of products sold on the market [

7,

8,

9]. The public anxiety about these consumer goods caused the emergence of a new terms such as “Checksumer,” Researsumer, and Smarsumer; consumers who search for various information and decide to make a purchase are “checksumer,” a combination of “check” and “consumer”; consumers researching and exploring areas of interest refer to researchers and consumers as “researsumer.” They are also known as “smarsumer,” a combination word of smart and consumer, who purchases the consumer goods after confirming the ingredients and raw materials of the product [

10]. The emphasis of research about human safety of synthetic chemicals outweigh natural ingredients [

11,

12,

13], while natural materials are still of toxicological concerns [

14,

15,

16]. Through a simple Internet search or Mintel GNPD data [

17], the number of ingredients in the cosmetics marketed is usually over 20. It is not so difficult to find cosmetics containing more than 40 ingredients. In this vein, the consumers’ loyalty and trust to famous and big brand cosmetics in terms of safety has been receded nowadays, and the external cue effect of brand loyalty is relatively weakening. Smartphone applications (apps) are beginning to emerge to alleviate these consumer anxieties. Typical examples are apps such as “Hwahae” and “Glowpick” that display the hazard ratings of cosmetic ingredients and identify ingredients that may be toxic or allergic to the skin [

18]. For every product, the apps show a full list of the ingredients it contains with a one-to-ten scale indicator of harmfulness to the skin. These apps help consumers decode unfamiliar chemical ingredients and become increasingly clever and choose to rely on less subjective assessments [

19].

Unlike medicines that are used only when health problems occur, cosmetics are a daily necessity concept, regardless of the presence or absence of a disease, so the ingredients of the product are exposed to the human body every day [

20,

21], and consequently, the human safety features as well as skin beauty features such as moisturizing, anti-aging, or sun protection are essential requirements for the purchase of cosmetics [

22]. In line with this context, there are numerous studies on the safety of cosmetics. In other words, studies allied with the risks and regulations of trace harmful chemicals [

16,

20,

21,

23] and the association between organic/natural ingredients and the safety of cosmetics [

24] (some of them argue that organic and natural cosmetics lead to positive effect on consumers’ purchase intentions [

12,

13,

25] but on the other hand, contrary to general belief, there are many reports that natural cosmetic ingredients are not free from toxicity [

26,

27]) are visible. However, researches based on consumers’ perception of quality and their trust in accessible information of safety data to them actually and their purchase intentions related to the safety of cosmetics of consumers are rare.

Quality perceived by consumers are classified into intrinsic signal related to the physical composition of the product such as the flavor, color, texture, and durability of the product, and external signals associated with the brand name or product price or reputation of the store, which are product-related but not part of the physical product itself [

28,

29]. Consumers perceive products with these signals as precious products by utilizing excellent quality and performance as signals. In other words, good quality is one of the reasons consumers buy precious goods [

30,

31]. Quality is a functional value or utility value that represents the uniqueness, usefulness, reliability, and durability of a product, and quality-oriented consumers tend to be rational to focus on the highest level of products as well as finding the right price and quality combination for their purchase [

32,

33]. Signal theory also suggests that trustworthiness is a key determinant of brand signals for effectively communicating information [

34]. This means that brands can be a trusty signal because they can implement the cumulative effort of a premarket communication strategy. In other words, brand trust is at the core of the brand as a signal [

35,

36]. Given the possibility of using the brand as a signal, brand trust and brand reputation can affect consumers’ brand purchase intentions, as they can increase their confidence in brand choices and improve their social status and self-worth via purchasing the brand [

37]. However, other studies show that when faced with multiple signals, consumers can trust in a larger scope of signals to make decisions and the effect of other signals is attenuated [

38,

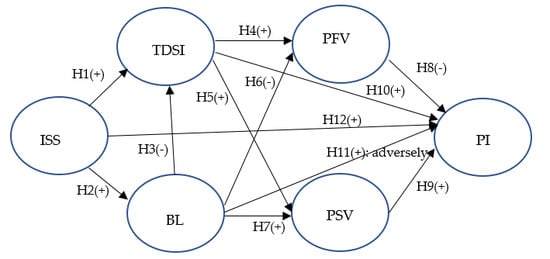

39]. As an example of the cosmetics industry, this can be explained by drawing two signals, brand and information of safety rating for all ingredients of cosmetic formulations provided by a domain-specific organization. In this case, the signals are not complementary to each other, but the brand and domain specific information are mutually independent and conflicting; only the larger scope out of the two signals influences the consumer decision-making and the other is weakened. As a result of a series of safety incidents in consumer products, Korean consumers’ brand confidence has weakened in line with the chemical phobia atmosphere in the society that caused safety problems in renowned brand/products by multinational chemical companies and big local cosmetic makers. Consequently, our research model was designed focusing on the signal of trust in domain-specific safety information for cosmetic ingredients while involving the variable of brand loyalty.

In the end, these contextual backgrounds motivated us to address the following three research questions. First, how will trust in domain specific information on the safety rating of cosmetic ingredients influence consumers’ perceived values and intentions to purchase cosmetics formulated with high safety grade ingredients (named as green-grade cosmetics here)? Second, how is individuals’ brand loyalty associated with their perceived values and purchase intentions for these green-grade cosmetics? Third, what decisions on marketing and sales strategies can cosmetic makers and e-commerce vendors make from the results of this study?

3. Research Methodology

To test the research model, an experimental methodology was employed. First, a mobile app that resembles an actual mobile app available in the domain was created. Although not having a billing feature, the mobile app was designed to look analogous to regular mobile e-commerce. For the sake of making it easier for participants to concentrate on their apps without spending a long time before responding to the survey, the app was simplified and only seven cosmetics were included. Similar to the form provided by Hwahae and Glowpick, we have entered all the ingredients and their hazard ratings for the seven products (see

Figure 4). Since Hwahae and Glowpick’s hazardousness criteria of individual ingredients are based primarily on the EWG’s Skin Deep

® Cosmetics Database provided by Environmental Working Group (EWG) [

72,

95] which is a non-profit, non-partisan organization with the purpose of establishment to protect human health and the environment, our study also identified the hazard classes of each ingredient utilizing EWG’s Skin Deep

® Cosmetic database [

95] (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Two of the seven selected products were famous branded products made by Korean cosmetics companies which ranked first and second in sales; the two products were indie cosmetics that are on the rise, and the remaining goods were new launching products of startup companies. For the convenience of the experiment, some modifications were made to the product names and the components. However, the brand names were used without adjustment as they were in the market.

Similar to EWG’s method of marking as green-grades for high-safety cosmetics and their ingredients, in our study, such products or materials were called green-grade cosmetics or ingredients. In addition, we calculated the safety levels of individual commercial formulations by averaging the safety ratings of all the ingredients, and seven of the finished products with green- grade results were placed in the mobile e-commerce store developed for this study.

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

The population of this study included women in their late teens to fifties and men in their twenties to thirties who live in Seoul, Inchon, and Kyunggi-do of South Korea and purchase skin-care cosmetics through mobile apps. About 50% of the South Korea’s total population lives in Seoul [

98], Incheon, and Gyeonggi-do, and these areas are also leading the trends as a center of South Korea’s economy and culture. Non-probability sampling was employed over a period of 24 days from 27 July to 19 August 2019. Purposive sampling [

11] was employed by determining the specific sample on the basis of their relevance on the study and their experience on mobile commerce. The sample consisted of undergraduates, MBA students, and the alumni association members of a business school in Sungkyunkwan university of South Korea and their family, friends, company colleagues, and other acquaintances, who were recruited through multi-level online communication process. Each study participant was requested to download one of open apps and an experimental app and answer a questionnaire after reviewing the apps. The online survey was conducted using the Google Forms tool to collect data for the empirical analysis. A total of subjects was recruited and rewarded with a beverage coupon equivalent to about 4000 KRW. We analyzed data from 240 respondents who completed the entire survey; four incomplete answers were removed. High response rates meant no serious problems concerned with non-response bias [

11]. In this study, female comprised 74.2% of the respondents, while the majority were between 18 and 30 years old (88.7%) and university students (66.3%) who are generally known as the generations that are sensitive to new trends and relatively active in utilizing mobile apps and mobile shopping. Based on the general conjecture that the main consumer groups buying cosmetics through mobile apps are women in their late teens and 20s, sampling for our study was conducted. As yet, we couldn’t rule out that these purchases are being made in other groups, so we decided to involve some percentage of other age groups and men into our experiments. Men’s responses, 25.8% of the total response rate, were used in our study, according to Euromonitor’s 2018 statistics (fee accessible service, [

99]). Men’s cosmetics accounted for 17% of the general skin-care cosmetics sales in South Korea and respecting the advice of three cosmetics industry experts that the use of male consumers in sunscreen cosmetics and women’s cosmetics is increasing. Most non-college respondents have a bachelor’s degree or higher. In addition, for cosmetics purchases, 29.6% of respondents spend between KRW10,000 and KRW20,000 a month, and the other 29.6% spend between KRW20,000 and KRW50,000 a month. The descriptive statistics of the samples are listed in

Table 1.

Instead of the mobile app registered in the market, the participants were required to download and use the trial version, so we hired four experimental assistants to recruit suitable participants and help them download the mobile app. Most of the communication between respondents and experimental assistants was through mobile messengers. Because this trial mobile app did not work on the IOS operating system and only runs on the Android environment, there was a limit to participate Apple phone users in our experiment.

3.2. Measures

They were asked to check out the Hwahae or Glowpick apps that are available from “Google play store” and to browse them for ten minutes (80.4% of the participants close Hwahae app; see

Table 1) before downloading the research app that takes stock of seven commercial cosmetic formulations, e.g., three skin hydrating creams, two sunscreen creams, an eye cream, and a skin toner. Subsequently, the respondents were asked to look around the research app for five minutes before engaging in the survey. In the sense that potentially high non-response rates or reluctancy on taking required actions because of sort of concern about financial safety issues could occur when the participants were requested to make an actual decision of clicking on a purchase function key or feedback through transaction pages, a survey response method was utilized.

The reminder of the survey contained several items intended to measure TDSI, BL, PFV, PSV, PI, and individual characteristics (demographics). No control variable was specifically used since the study was designed so that the participants who are accustomed to using mobile app and have experience in purchasing cosmetics via mobile commerce, are supposed to respond after using the mobile apps. All items shown in

Table 2 were measured on a seven-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Prior to analyzing the proposed research model, the first step was to verify the reliability and convergent validity of the survey items, and the factor loading values had to exceed the recommended minimum measurement (0.7) to evidence that every item is an appropriate explanation for the dimensionality of the factors [

1,

2]. In this study, after conducting the construct validity measurement using item loading, average variance extraction (AVE) and composite reliability (CR), we had to ensure that Cronbach’s α, factor loading, and CR were more than 0.7 and AVE was more than 0.5 [

100,

101], for the sake of validity acceptance [

11,

102].

3.3. Statistical Analyses

For the sake of testing the validity of the proposed research model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted employing structural equation modeling (SEM), run via AMOS software, which allows causality models with latent variables using maximum likelihood estimation [

109,

110]. The model validity, which stands for validity of the relationship between six latent variables with eleven hypothesized relationships, were tested utilizing CFA, while the model reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha. The model validity was assessed by inspecting the overall fit and construct validity; (1) besides, we calculated

(relative chi-square), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), incremental fit index (IFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), to verify that the model showed acceptable fit [

105]; (2) item loading, AVE, and CR were evaluated for the construct validity measures.

5. Discussion

The aim of our study was to investigate the effects of factors such as involvement in skin safety, trust in domain specific information, and perceived safety and social values of green grade cosmetics, on purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics. Brand loyalty factor was also considered for our research model. For the sake of manipulating the respondents’ context as identical as possible, we created a simple mobile e-commerce app and used it as a stimulus for this study. Through the mobile shopping mall, we provided information on the safety ratings of all ingredients and their average safety level for individual cosmetic products according to a standard sourced by a non-profit, non-partisan organization (e.g., EWG’s Skin Deep

® Cosmetic Guide) [

95], and made up only the cosmetic products with high skin safety ratings (commonly referred to as green-grade cosmetics). Besides, in order to minimize the variance between the respondents’ understanding level of the research app and the proficiency of its use, respondents were instructed to preview the Hwahae and Glowpick apps, which provided a safety rating for each ingredients of cosmetic products in a similar way to the research app.

5.1. Key Findings

Involvement in skin safety (β = 0.508, t = 7.716) had a strong positive effect on trust in domain-specific information for safety rating of cosmetic ingredients; that is, it has been found that consumers who place more importance on skin safety when purchasing cosmetics show greater confidence in the information on the safety ratings of product ingredients from third-party agencies specialized in the cosmetics industry such as EWG. In addition, our finding indicated that the higher the level of involvement in skin safety, the higher the brand loyalty, as H1 was supported; it can be inferred that the expectation that a certain brand of cosmetics will be safe for the skin is a reason consumers are loyal to the brand. We speculated that based on the inference that consumers who show high loyalty to a particular brand are likely to be more largely engaged in quality of cosmetics, they will show greater trust on skin safety data of cosmetic raw materials rated according to certain criteria; however, there was no relationship between brand loyalty and trust in domain-specific information of skin safety for cosmetic ingredients, which was different from our assumption (H3 was rejected).

Trust in domain-specific information of the safety for cosmetic ingredients had a very strong positive effect on perceived safety value of green-grade cosmetics (β = 0.704, t = 11.299), but our test result showed that the perceived safety value did not affect the purchase intention (β = 0.044, t = 0.490). On the other hand, our test results verified that the trust in domain-specific information has a strong positive influence on perceived social value of green-grade cosmetics (β = 0.610, t = 9.992), and subsequently the perceived social values (β = 0.255, t = 3.238) affected the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics at a significant level. Meanwhile, involvement in skin safety in skin safety of cosmetics (β = 0.165, t = 2.341) and trust in domain-specific information of skin safety for cosmetic ingredients (β = 0.286, t = 2.580) had a positive effect on the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics. These findings suggest that although the perceived importance of consumers on skin safety and trust of the related information from specialized agencies in this domain are important factors in the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics and the trust is also very important to the perceived safety value of their perceived green-grade cosmetics, the perceived safety value does not lead to the purchase intention of their green-grade cosmetics; instead, our test results state that their perceived social value for green-grade cosmetics directly effects the purchase intention of those products. These results imply that the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics is not driven by the perceived safety value of safety for those cosmetics but motivated by perceived social value such as social recognition or pride in using the cosmetics with green concept.

Brand loyalty did not affect the perceived safety value (β = 0.063, t = 1.195) of green-grade cosmetics but was found to be a cause for the perceived social value (β = 0.159, t = 2.907) of such products. Besides, brand loyalty (β= −0.125, t= −2.519) had an adverse effect on the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics. From these results, it is interpreted that consumers with higher brand loyalty put more weight on perceived social values, such as public recognition and solidarity as members of society, rather than just on the perceived safety value for green-grade cosmetics. Since consumers with higher brand loyalty show lower brand switching intention [

101], it is inferred that despite the positive effect on perceived social value of brand loyalty, the factor has an adverse impact on the intention to purchase green-grade cosmetics, which may be an alternative to brand cosmetics.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

We originally designed a conceptual framework with PFV and PSV, including perceived emotion value (PEV) latent variables. However, the PEV factor was removed in consideration of the study purpose and model suitability, since the distinction of PEV and PFV variables was not clear and the construct validity was not secured, while processing the explanatory factor analysis (EFA). Although PFV did not have a significant effect on PI, PSV showed a positive effect on the dependent variable, so we conducted an additional analysis of our model by substituting PFV latent variable to perceived emotion value and verified its construct validity, reliability, and goodness of fit indices for the research model (see the results from

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3). Like PSV, perceived emotion value of green-grade cosmetics was found to positively influence the purchase intention of those products. It is interpreted that respondents perceive the terms green color and green-grade as “green” in a broader sense than the scope of safety of the ingredients, given that EWG ’s Skin Deep [

72], our research app, Hwahae, and Glowpick are displaying and communicating with consumers on safe grades of cosmetic ingredients. It is inductively inferred that the broader meaning of the term “green” in an intuitive sense based on respondents’ life experiences acted as an important signal, and it had an important influence on the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics. In other words, it is assumed that the word “green” and its color image acted as an environmental stimuli leading to emotional response, based upon stimulus-organism-responses (SOR) theory; “green” as an environmental stimulus (S) called emotional reactions (O), which in turn derived consumers’ purchase intention (R) [

103,

107,

121].

5.3. Practical Implications

From our hypothesis testing, we ascertained that the higher the involvement in skin safety, the higher the trust in domain specific information, and the lower the brand loyalty and the greater the consumer’s intention to purchase green-grade cosmetics. Given those results, the following suggestions may be given to the stakeholders related to a cosmetic business: (1) New entrants to the cosmetic business or companies with relatively weak brand power will be able to facilitate consumer purchases by developing and promoting green-concept cosmetics while using information from human safety databases from domain specific organizations; (2) cosmetic manufacturers and sellers through mobile commerce will be encouraged to have consumer communications in a clear and compelling and legible sentence on the mobile shopping window with evidence on the skin safety of green-grade cosmetics; (3) manufacturers with relatively weak brand power are encouraged to identify credible specialist agencies that can ensure trust in the safety of cosmetic ingredients in terms of both breadth and depth, and are imperative to construct ample databases with diverse types of safety criteria and data, which convince consumers; (4) sellers via mobile commerce will also be able to build these databases, establish sellers’ criteria for green-grade cosmetics, and share this information with consumers and their suppliers (i.e., manufacturers) to increase transparency and persuasion, which may lead to stimulating consumers’ purchases and engaging more partners.

In addition, perceived social value also had a positive effect on the purchase intention of green-grade cosmetics, whereas perceived safety value of green-grade cosmetics was not a cause of purchase intention of the products. As stated in the previous section, consumers of green-grade cosmetics tend to purchase such products because of their social value such as social recognition, acceptance, and pride rather than the functional value of the product. These results may be interpreted that the functional value of the green-grade cosmetics’ safety attribute alone is difficult to meet the usefulness of consumers to determine their purchase. From the positive effects of social value on purchasing intentions, it is expected to lead business growth that e-commerce sellers and cosmetics manufacturers share a portion of their sales revenues with those located at bottom of pyramid (BOP) [

122], e.g., through sponsoring low-income patients with skin diseases or certain organization such as international relief NGOs.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study still has some limitations and shortcomings in this paper that need further exploration in the future. First, although the mobile commerce app was developed to realistically design the experimental situation, the data of the structures used in this study were self-reported and may contain some biases. The measurement of the variables, ISS, TDSI, BL, PFV, PSV, and PI, is based on subjective response. Because capturing consumers’ ideas and thoughts lack a longitudinal analysis of customer behavior, future research will call more direct data that encourage consumers to click on purchase function keys and write review texts in e-commerce mobile apps developed for research purposes. By analyzing those data, we will be able to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how domain specific information of safety data for cosmetics affects the purchase intention. Second, since we were limited in finding statistics showing the percentage of consumers purchasing cosmetic products through mobile shopping by age, gender, and income, rather than the optimal sample elements, we relied on a paid industry statistic such as Eurominitor data and advices from industry experts. Third, this trial mobile app did not work on the iOS operating system and only ran in the Android environment, so there was a limit to involving Apple phone users in the experiment. In the future study, research apps could actually register the Android and IOS app markets, improving the flexibility of sampling by allowing subjects to use them without inconvenience.