Sustainability and Branding in Retail: A Model of Chain of Effects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

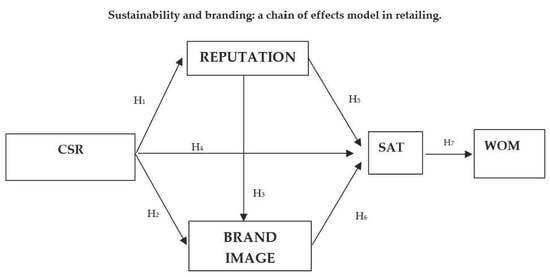

2. Theoretical Background and Developed Hypotheses

2.1. CSR, Brand Image and Reputation

2.2. CSR and Satisfaction

2.3. Satisfaction and WOM

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| CONSTRUCT/ITEMS | Mean | St Dev |

|---|---|---|

| BRAND IMAGE (B IMAG) [53] (0.818; 0.879; 0.645) | ||

| B1. The [brand] logo is easily recognised. | 6.635 | 3.500 |

| B2. My social environment is aware of the values conveyed by [brand]. | 5.087 | 1.407 |

| B3. I think [brand] stands out among its competitors. | 6.092 | 1.061 |

| B4. I think [brand] is easily remembered by consumers. | 6.427 | 0.959 |

| B5. Society can rely on [brand]. | 5.481 | 1.345 |

| CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (CSR) [53] (0.898; 0.929; 0.766) | ||

| CSR1. I consider [brand] to be socially responsible. | 4.868 | 1.398 |

| CSR2. [Brand] is committed to promoting well-being in society. | 4.789 | 1.462 |

| CSR3. [Brand] is environmentally friendly. | 4.697 | 1.513 |

| CSR4. The human resources management of [brand] goes beyond legal requirements. | 4.530 | 1.416 |

| REPUTATION (REP) [59] (0.900; 0.926; 0.717) | ||

| R1. I think [brand] has a good reputation. | 5.608 | 1.351 |

| R2. I think [brand] is well known. | 6.467 | 0.997 |

| R3. I think [brand] is admired. | 5.583 | 1.280 |

| R4. I think [brand] is prestigious. | 5.811 | 1.248 |

| R5. Overall, I think [brand] has a good reputation. | 5.759 | 1.260 |

| SATISFACTION (SAT) [84] (0.949; 0.963; 0.867) | ||

| S1. My relationship with [brand] has been positive. | 4.772 | 1.596 |

| S2. Compared to what my ideal relationship would be, I am very satisfied with my relationship with [brand]. | 4.752 | 1.535 |

| S3. Overall, I am very satisfied with [brand]. | 5.005 | 1.449 |

| S4. I am very satisfied with [brand], as it has fulfilled my expectations. | 4.968 | 1.488 |

| WORD OF MOUTH (WOM) [90] (0.869; 0.938; 0.883) | ||

| WOM1. I like to share my experiences as a [brand] customer with others. | 4.417 | 1.701 |

| WOM2. I’ll recommend [brand] to friends and family. | 4.643 | 1.663 |

| WOM3. I always give my honest opinion about [brand] services. | 5.821 | 1.339 |

References

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero-Polo, I.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J.J. Sustainability and Business Outcomes in the Context of SMEs: Comparing Family Firms vs. Non-Family Firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olsson, J.; Hellström, D.; Palsson, H. Framework of Last Mile Logistics Research: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Valenciano, J.D.P. Sustainability and Retail: Analysis of Global Research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Mei, L. Sustainable Development in the Service Industry: Managerial Learning and Management Improvement of Chinese Retailers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rao, F. Resilient Forms of Shopping Centers Amid the Rise of Online Retailing: Towards the Urban Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Claro, D.P.; Silvio Abrahao, L.N.; de Priscila Borin, O.C. Sustainability drivers in food retail. J. Ret. Cons. Serv. 2013, 20, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meise, J.N.; Rudolph, T.; Kenning, P.; Phillips, D.M. Feed them facts: Value perceptions and consumer use of sustainability-related product information. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessous, A.; Boncori, A.-L.; Paché, G. Are consumers sensitive to large retailers’ sustainable practices? A semiotic analysis in the French context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.; Kotler, P.; Harker, M.; Brennan, R. Marketing: An Introduction; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Kumar, V. Drivers of brand community engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Mele, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Miocevic, D. The power of emotional value: Moderating customer orientation effect in professional business services relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Milan, A.; Felix, R.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Hinsch, C. Strategic customer engagement marketing: A decision making framework. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Foroudi, P.; Yen, D. Investigating relationship types for creating brand value for resellers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 72, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardoni, A.; Kiseleva, E.; Taticchi, P. In Search of Sustainable Value: A Structured Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A. The Evolution of Business Groups’ Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 153, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirodkar, V.; Beddewela, E.; Richter, U.H. Firm-Level Determinants of Political CSR in Emerging Economies: Evidence from India. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 148, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.M.-D.; Amores-Salvadó, J.; Navas-López, J.E. Environmental Management Systems and Firm Performance: Improving Firm Environmental Policy through Stakeholder Engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Investigating Stakeholder Theory and Social Capital: CSR in Large Firms and SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saridakis, C.; Angelidou, S.; Woodside, A.G. What type of CSR engagement suits my firm best? Evidence from an abductively-derived typology. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 108, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility: A Scale Development Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.D.T.; Van Der Meer, M. How Does It Fit? Exploring the Congruence Between Organizations and Their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Activities. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiessling, T.; Isaksson, L.; Yasar, B. Market Orientation and CSR: Performance Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskentli, S.; Sen, S.; Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C. Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of CSR domains. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.T.; Nguyen, N.; Pervan, S. Retailer corporate social responsibility and consumer citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of perceived consumer effectiveness and consumer trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E.; Kantur, D.; Maden, C.; Telci, E.E.; Arıkan, E. Investigating the mediating role of corporate reputation on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and multiple stakeholder outcomes. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasuwa, G. Do the ends justify the means? How altruistic values moderate consumer responses to corporate social initiatives. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3714–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cesar, S.; Jhony, O. Corporate Social Responsibility supports the construction of a strong social capital in the mining context: Evidence from Peru. J. Cl. Prod. 2020, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Cowley, J. The Relevance of Stakeholder Theory and Social Capital Theory in the Context of CSR in SMEs: An Australian Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Wang, L.; Zou, H.; Ma, H. How Does Environmental Irresponsibility Impair Corporate Reputation? A Multi-Method Investigation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaland, A.J.S.; Lwin, M.O.; Murphy, P.E. Consumer Perceptions of the Antecedents and Consequences of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H. The Effect of CSR Fit and CSR Authenticity on the Brand Attitude. Sustainability 2020, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, K.-T. The Advertising Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and Brand Equity: Evidence from the Life Insurance Industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Gupta, N. Effect of corporate environmental sustainability on dimensions of firm performance—Towards sustainable development: Evidence from India. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications for Strategy Formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martelo, S.; Barroso-Castro, C.; Cepeda, G.; Martelo-Landroguez, S. The use of organizational capabilities to increase customer value. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2042–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P.; Davari, A.; Srivastava, S.; Paswan, A.K. Market orientation, brand management processes and brand performance. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C.; Guzmán, F. The evolution of brand management thinking over the last 25 years as recorded in the Journal of Product and Brand Management. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malär, L.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D.; Nyffenegger, B. Emotional Brand Attachment and Brand Personality: The Relative Importance of the Actual and the Ideal Self. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetscherin, M.; Guzmán, F.; Veloutsou, C.; Cayolla, R.R. Latest research on brand relationships: Introduction to the special issue. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.J.; Muñiz, A.M.; Arnould, E.J. How Brand Community Practices Create Value. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Guzmán, F. How CSR reputation, sustainability signals, and country-of-origin sustainability reputation contribute to corporate brand performance: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C. Reputation. In Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, S. The Role of Corporate Reputation in Determining Investor Satisfaction and Loyalty. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehtap, O.; Kokalan, O. The relationship between corporate reputation and organizational citizenship behavior: A comparative study on TV companies and banks. Qual. Quant. 2012, 47, 3609–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Bijmolt, T.H.; Tribo, J.A.; Verhoef, P. Generating global brand equity through corporate social responsibility to key stakeholders. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; De Chernatony, L. The power of emotion: Brand communication in business-to-business markets. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 11, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; Saha, R.; Goswami, S.; Dahiya, R. Consumer’s response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.; Zeithaml, V.; Lemmon, K. Driving Customer Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Sun, S. Building Consumer-Oriented CSR Differentiation Strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holt, D.B.; Quelch, J.A.; Taylor, E.L. How global brands compete. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración 2014, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T.; Garrido-Morgado, A. Corporate Reputation: A Combination of Social Responsibility and Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Corporate Reputation and Social Performance: The Importance of Fit. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritsen, B.D.; Perks, K.J. The influence of interactive, non-interactive, implicit and explicit CSR communication on young adults’ perception of UK supermarkets’ corporate brand image and reputation. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2015, 20, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popoli, P. Linking CSR strategy and brand image. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Hernández, J.A.; Cambra-Fierro, J.J.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R. Sustainability, brand image, reputation and financial value: Manager perceptions in an emerging economy context. Sustain. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugre, J.B.; Anlesinya, A. Corporate social responsibility strategy and economic business value of multinational companies in emerging economies: The mediating role of corporate reputation. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2020, 3, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratihari, S.K.; Uzma, S.H.; Balmer, J. CSR and corporate branding effect on brand loyalty: A study on Indian banking industry. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-S.; Chiu, C.-J.; Yang, C.-F.; Pai, D.-C. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Performance: The Mediating Effect of Industrial Brand Equity and Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P.; Ketola, T. Corporate Responsibility and Identity: From a Stakeholder to an Awareness Approach. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2012, 21, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. How Customer Support for Corporate Social Responsibility Influences the Image of Companies: Evidence from the Banking Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, H. Corporate social responsibility as an organization attractiveness for prospective public relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Dacin, P. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galbreath, J. Building corporate social responsibility into strategy. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2009, 21, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Harrison, D.E.; Ferrell, L.; Hair, J.F. Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Narus, J. A model of distributor’s perspective of distributor-manufacturer working relationships. J. Mark. 1984, 48, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. Consumer socially sustainable consumption: The perspective toward corporate social responsibility, perspective value, and brand loyalty. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 13, 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, H.; Li, Y. CSR and Service Brand: The Mediating Effect of Brand Identification and Moderating Effect of Service Quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 100, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffie, S. Positioning strategies for branding services in an emerging economy. J. Strat. Mark. 2018, 28, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R. Brand marketing programs and consumer loyalty—Evidence from mobile phone users in an emerging market. J. Prod. B. Manag. 2016, 25, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Alexander, C. The companies with the best CSR reputations. Forbes, 2 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cambra-Fierro, J.J.; Polo-Redondo, Y. Long-term Orientation of the Supply Function in the SME Context. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2008, 26, 619–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, C.; Arikan, E.; Telci, E.; Kantur, D.; Arıkan, E. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility to Corporate Reputation: A Study on Understanding Behavioral Consequences. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, B.A.; Bell, S.; Mengüç, B. Corporate reputation, stakeholders and the social performance-financial performance relationship. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Rashid, B. A conceptual model of corporate social responsibility dimensions, brand image, and customer satisfaction in Malaysian hotel industry. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grott, E.M.; Cambra-Fierro, J.; Perez, L.; Yani-De-Soriano, M. How cross-culture affects the outcomes of co-creation. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 544–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, J. Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product. J. Mark. Res. 1967, 4, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: A pilot study. J. Mark. 1983, 47, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, N.Y.; Seock, Y.-K. Effect of service recovery on customers’ perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruvian Institute of Statistics and Computing. Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/ (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Atradius. Available online: https://group.atradius.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Kok, W.; Fon, S. Shopper perception and loyalty: A stochastic approach to modeling shopping mall behavior. Int. J Ret. Dist. Manag. 2014, 42, 626–642. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, A.; Hair, J. An assessment of the mall intercept as a data collection method. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yani-De-Soriano, M.; Hanel, P.H.; Vazquez-Carrasco, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J.; Wilson, A.; Centeno, E. Investigating the role of customers’ perceptions of employee effort and justice in service recovery. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 708–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keillor, B.D.; Lewison, D.; Hult, G.T.M.; Hauser, W. The service encounter in a multi-national context. J. Serv. Mark. 2007, 21, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. Bridging Design and Behavioral Research with Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. On comparingr from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five perspectives and five recommendations. Mark. ZFP 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.; Zeller, R. Reliability and Validity Asses Sment; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hil: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.; Miller, N. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Pozza, I.D.; Ganesh, J. Revisiting the Satisfaction–Loyalty Relationship: Empirical Generalizations and Directions for Future Research. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Universe | Consumers of Food and Beverage Products, over 18 Years of Age, from the Metropolitan Lima Area (Peru) |

|---|---|

| Sample size | 403 |

| Geographical scope | National. Peru |

| Sampling method | Random quota |

| Fieldwork | October-December, 2018 |

| Sampling error | 4.9% (p = q = 0.5; z = 1.96; 95%) |

| Analysis of information | PLS Software (SmartPLS 3.2.7) |

| Brand Image | CSR | Reputation | Satisfaction | WOM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand image | 0.803 | ||||

| CSR | 0.578 | 0.875 | |||

| Reputation | 0.798 | 0.563 | 0.847 | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.603 | 0.569 | 0.570 | 0.931 | |

| WOM | 0.508 | 0.512 | 0.479 | 0.723 | 0.94 |

| Hypothesis | B | t-Value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: CSR −> REP | 0.153 ** | 3.048 | 0.652 |

| H2: CSR −> B IMAG | 0.578 *** | 15.986 | |

| H3: REP −> B IMAG | 0.709 *** | 16.054 | 0.334 |

| H4: CSR −> SAT | 0.307 *** | 4.909 | 0.445 |

| H5: REP −> SAT | 0.159 * | 1.948 | |

| H6: B IMAG −> SAT | 0.298 *** | 4.663 | |

| H7: SAT −> WOM | 0.723 *** | 27.301 | 0.522 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Flores-Hernández, A.; Olavarría-Jaraba, A.; Valera-Blanes, G.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R. Sustainability and Branding in Retail: A Model of Chain of Effects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145800

Flores-Hernández A, Olavarría-Jaraba A, Valera-Blanes G, Vázquez-Carrasco R. Sustainability and Branding in Retail: A Model of Chain of Effects. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145800

Chicago/Turabian StyleFlores-Hernández, Alfredo, Ana Olavarría-Jaraba, Guadalupe Valera-Blanes, and Rosario Vázquez-Carrasco. 2020. "Sustainability and Branding in Retail: A Model of Chain of Effects" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145800

APA StyleFlores-Hernández, A., Olavarría-Jaraba, A., Valera-Blanes, G., & Vázquez-Carrasco, R. (2020). Sustainability and Branding in Retail: A Model of Chain of Effects. Sustainability, 12(14), 5800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145800