Challenges for Protected Areas Management in China

Abstract

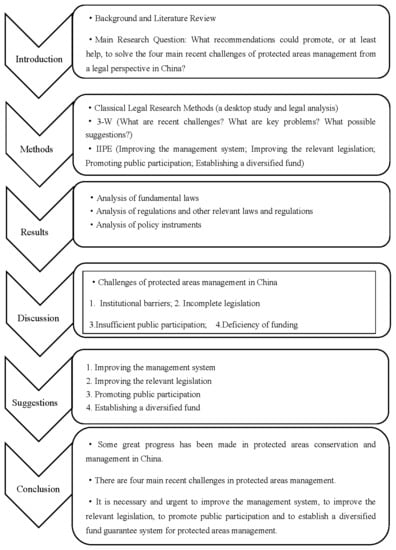

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results: Laws, Regulations and Policy on Protected Areas Management in China

3.1. Fundamental Laws

3.2. Regulations for Nature Reserves

3.3. Other Relevant Laws and Regulations

3.4. Policy Instruments

3.4.1. The Initiative Period: From 1991 Till 2010

3.4.2. The Rapid Development Period: From 2011 Till 2020

4. Discussion: Challenges of Protected Areas Management

4.1. Institutional Barriers

4.2. Incomplete Legislation

4.2.1. No Comprehensive Law Covering All Types of Protected Areas

4.2.2. Challenges after Issuing a Specific Law for National Parks

4.2.3. Other Gaps in the Existing Legislation

4.3. Insufficient Public Participation

4.3.1. Limitations for Public Participation

4.3.2. Analysis of the Right to Participation in Protected Areas

4.4. Deficiency of Funding for Protected Areas

4.4.1. Limited Financial Sources

4.4.2. Subsidies for Protected Areas

4.4.3. Problems in the Use of Funding

5. Suggestions for Better Protected Areas Management in China

5.1. Improving the Management System by Establishing “One Type of Protected Areas, One Law or Regulation” System

5.2. Improving the Relevant Legislation

5.2.1. Towards a Comprehensive Legislative System for Protected Areas

5.2.2. Key challenges for a Comprehensive Legislative System on Protected Areas

5.3. Promoting Public Participation

5.3.1. From ‘Passive Participation’ to ‘Active Participation’

5.3.2. Some Improvements on Public Participation in the Recent Regulations and Policies

5.3.3. Recent Improvements in Practice

5.4. Establishing a Diversified Funding Guarantee System

5.4.1. Shortage of Funding for Protected Areas Management

5.4.2. Establishing a Diversified Financing Mechanism

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- He, M. A Human Rights-Based Approach to Conserving Protected Areas in China: Lessons from Europe; Intersentia Publisher: Antwerp, Belgium, 2016; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lopoukhine, N.; Crawhall, N.; Dudley, N.; Figgis, P.; Karibuhoye, C.; Laffoley, D.; Miranda Londono, J.; Mackinnon, K.; Sandwith, T. Protected Areas: Providing Natural Solutions to 21st Century Challenges. S.A.P.I.EN.S (Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society) [Online], Online Since 10 August 2012; Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1254 (accessed on 30 September 2016).

- TEEB. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity in National and International Policy Making; Ten Brink, P., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: http://img.teebweb.org/wp-content/uploads/Study%20and%20Reports/Reports/National%20and%20International%20Policy%20Making/Executive%20Summary/National%20Executive%20Summary_%20English.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Mulongoy, K.J.; Gidda, S.B. The value of nature: Ecological, economic, cultural and social benefits of protected areas. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2008, 73, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Protected Planet. May 2020 Update of the WDPA. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/c/monthly-updates/2020/may-2020-update-of-the-wdpa (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Aichi Biodiversity Targets, UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/X/2 (29 October 2010).

- Protected Planet. Aichi Target 11 Dashboard. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/target-11-dashboard (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Cliquet, A.; Schoukens, H. Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat, Ramsar, 2 February 1971, (1972) 11 ILM 963; Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Paris, 16 November 1972, (1972) 11 ILM 1358; Convention on Biological Diversity, 5 June 1992, (1992) 31 ILM 818; on international law on protected areas. Terrestrial protected areas. In Biodiversity and Nature Protection Law, Encyclopedia of Environmental Law; Razzaque, J., Morgera, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Cliquet, A. Sustainable development through a rights-based approach to conserve protected areas in China. China-EU Law J. 2014, 3, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area Profile for China from the World Database of Protected Areas. May 2020. Available online: www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- CBD. Sixth National Report for the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2018. Available online: https://chm.cbd.int/database/record/C7B6BC32-C06D-B09C-BFF8-7D265F24DBE6 (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- People’s Daily; People’s Daily Publisher: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 14.

- Protected Areas in China Occupy Nearly 15% of the Territory. Issued on 13:55; China National Radio: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Peng, J. Protected areas system with national parks as the main body: Connotation, composition and construction path. J. Beijing. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 1, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- The “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves” [中华人民共和国自然保护区条例] entered into effect on 1 December 1994 and was revised and promulgated on 7 October 2017 by “State Council Order No. 687” of the People’s Republic of China.

- IUCN protected areas management categories classify protected areas according to their management objectives. The categories are recognized by international bodies such as the United Nations and by many national governments as the global standard for defining and recording protected areas and as such are increasingly being incorporated into government legislation. IUCN protected areas management categories are la strict nature reserve, lb wilderness area, II national park, II natural monument or feature, IV habitat/species management area, V protected landscape/seascape, VI protected area with sustainable use of natural resources.

- Xie, Y. Comparison and reference of nature reserves in China and IUCN protected areas management categories. World Environ. 2016, 5, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Worboys, G.L.; Lockwood, M.; Kothari, A.; Feary, S.; Pulsford, L. (Eds.) Protected Area Governance and Management; The Australian National University Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Article 22 of the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves” focuses on the duties of the management authorities.

- The “Constitution of the People’s Republic of China” [中华人民共和国宪法] was adopted in 1982 and newly amended on 11 March 2018.

- The “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” [中华人民共和国环境保护法] was promulgated by Order No. 22 of the President of the People’s Republic of China on December 26 1989, and entered into effect on the date of promulgation.

- Article 17 states “The people’s governments at various levels shall take measures to conserve areas representing various types of natural ecological systems, areas with a natural distribution of rare and endangered wild animals and plants, areas where major sources of water are conserved, geological structures of major scientific and cultural value, famous areas where karst caves and fossil deposits are distributed, traces of glaciers, volcanos and hot springs, traces of human history, and ancient and precious trees. Damage to the mentioned-above shall be strictly forbidden”. Article 17 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) is the same as Article 29 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version). The “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version) [中华人民共和国环境保护法] was newly modified based on the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) on 24 April 2014 and entered into force on 1 January 2015.

- The term ‘nature reserve’ was adopted by most of the relevant regulations; however, at present, more people and NGOs view the term ‘protected areas’ as more formal and meaningful. For instance, the Nature Conservation Legislation Research Group has argued to replace the term ‘nature reserve’ with ‘protected areas’. This group was organized by Yan Xie from the Institute of Zoology in the Chinese Academy of Sciences and consisted of more than fifty experts in law, biology and other relevant aspects from universities, NGOs, local governments and so on. This paper adopts the more popular term ‘protected areas’, but when it refers to legal documents, it adopts ‘nature reserve’ to keep consistent with their translation.

- Article 18 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) does not exist in the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version). The “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version) [中华人民共和国环境保护法] was newly modified based on the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) on 24 April 2014 and entered into force on 1 January 2015.

- Article 19 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) [中华人民共和国环境保护法] is similar with Article 30 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version). Article 30 says “Exploitation and utilization of natural resources shall be developed in a rational way that conserves biological diversity and safeguards ecological security. Ecological protection and restoration programs shall be developed in accordance with laws and be implemented. For introduction of exotic species as well as the research, development and utilization of biotechnology, effective measures shall be taken to prevent destruction of biodiversity.” The “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version) [中华人民共和国环境保护法] was newly modified based on the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) on 24 April 2014 and entered into force on 1 January 2015.

- Regarding the hierarchy of legislative documents, generally speaking, there are six categories, namely law (法律), administrative regulation (行政法规), local regulation (地方性法规), autonomous regulation and separate regulation (自治条例和单行条例), department rule (部门规章) and local government rule (地方政府规章). The “Law” refers to the one enacted by the National People’s Congress (NPC) or its standing Committee.

- Article 5 of the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves” [中华人民共和国自然保护区条例].

- Article 32 and Article 33 of the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves” [中华人民共和国自然保护区条例].

- The “Law on the Wildlife Protection of the People’s Republic of China” [中华人民共和国野生动物保护法] was issued on 8 November 1988 and revised on 26 October 2018.

- The “Law on the Wild Plants Protection of the People’s Republic of China” [中华人民共和国野生植物保护法] was issued 30 September 1996 and entered into practice on 1 January 1997. It was revised on 7 October 2017.

- The “Forest Law of the People’ Republic of China” [中华人民共和国森林法] was adopted in 1984 and amended on 27 August 2009.

- The “Mineral Resources Law of the People’s Republic of China” [中华人民共和国矿产资源法] was adopted in 1989 and amended on 27 August 2009.

- The “Management Measures on the Special Marine Protected Areas” [海洋特别保护区管理办法] was issued by the State Oceanic Administration of the People’s Republic of China on 31August 2010. Although it is called and translated as “management measures”, it is a regulation for special marine protected areas in China.

- The “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention of Pollution Damage to the Marine Environment by Land-sourced Pollution” [中华人民共和国防治陆源污染物污染损害海洋环境管理条例] entered into effect on 1 August 1990.

- The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention of Environmental Pollution Caused by Solid Waste” [中华人民共和国固体废物污染环境防治法] was issued in 1995 and was amended on 25 June 2019.

- The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention and Control of Desertification” [中华人民共和国防沙治沙法] entered into effect on 31 August 2001 and was revised on 26 October 2018.

- SEPA, National 8th Five-Year Plan and Ten-Year Plan on Protection of Nature Reserve and Species [全国自然保护区和物种保护八五计划和十年规划], 1991.

- SEPA, Outline of the Development Plan for Nature Reserves in China (1996–2010) [中国自然保护区发展规划纲要(1996–2010年)], 1997.

- The “National Wildlife Conservation and Natural Reserve Construction General Plan” [全国野生动植物保护及自然保护区建设工程总体规划] Was Issued in 2001. Available online: http://www.beinet.net.cn/zcfg/gh/qggh/200802/P020080423597945791148.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Xu, J.C.; Melick, D. Towards Community-Driven Conservation in Southwest China: Reconciling State and Local Perceptions; Working Paper No. 52; ICRAF (International Center for Research in AgroForestry): Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- The “National Developmental Program on Forest Protected Areas (2006–2030)” [全国林业自然保护区发展规划(2006–2030年)] was issued by the State Forestry Bureau in 2006.

- The “Strategy and Action Plan for Biodiversity Preservation in China (2011–2030)” [中国生物多样性保护战略与行动计划(2011–2030)] was issued by the Chinese Environmental Protection Bureau on 17 September 2010. Although it is only a legal document from the Chinese Environmental Protection Bureau, it is regarded as guidelines for solving the relevant issues in China.

- The “Notification on Well Managing Protected Areas from the General Office of the State Council” [国务院办公厅关于做好自然保护区管理有关工作的通知] was issued in December 2010. Although it is called and translated as “Notification”, it is regarded as guidelines for implementing the relevant regulation and solving the relevant issues on protected areas in China.

- China Environmental Newspaper. Strengthen Protected Areas Management and Promote Ecological Civilization. 2010. Available online: http://www.clapv.org/weiquanwenxian_content.asp?id=175 (accessed on 8 October 2018). (In Chinese).

- The “Decisions of the CPC Central Committee on Several Major Issues Concerning Comprehensively Deepening Reform” [《中共中央关于全面深化改革若干重大问题的决定》] was published during the third plenary session of the 18th central committee on 15 November 2013.

- The “Notification on the Pilot Program of Establishing the National Park System” [《关于印发建立国家公园体制试点方案的通知》] was issued by the National Development and Reform Commission and other 12 Ministries in January 2015.

- Xinhua News(新华社). The General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued “Guidance on Establishing a System of Protected Areas with National Parks as the Main Body” [中共中央办公厅国务院办公厅印发《关于建立以国家公园为主体的自然保护地体系的指导意见》], 26 June 2019.

- Lv, Z.M. Some thoughts on the legislative system for protected areas with national parks as the main body. Biodiversity 2019, 27, 128–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.L. A Draft of China’s First National Parks Law Will Be Issued by THE End of This Year; China Daily: BeiJing, China, 2019; Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn (accessed on 9 July 2019). (In Chinese)

- OFweek Net. How Should China’s Nature Reserves Be Reformed. Shenzhen. 4 November 2016. Available online: https://ecep.ofweek.com/2016-11/ART-93000-8610-30062481.html (accessed on 25 May 2018).

- Ma, Y. Resolving Conflicts between Conservation and Recreation in Protected Areas: A Comparative Legal Analysis of the United States and China. Ph.D. Thesis, Dissertation in Erasmus School of Law, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Y. Thoughts and Suggestions on Protected Areas Establishment in the New Era. Qinhai Daily. 12 January 2018. Available online: http://bhq.papc.cn/sf_2E55FACFBE634AB69B8F7ADC42117FBF_262_isenlinzx.html (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Chen, J.K. Four Challenges in Biodiversity Conservation in China. In Proceedings of the Mainstreaming and Marketization of Biodiversity International Conference, Rome, Italy, 9 July 2016; Available online: http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2016-07-09/doc-ifxtwchx8368378.shtml (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- McElwee, C. Environmental Law in China: Mitigating Risk and Ensuring Compliance; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- For example, in 2012, an investment company was expected to spend up to 20 billion yuan to flatten 700 mountains in Lanzhou in the Gansu Province, which is one of China’s most chronically water-scarce cities, to build a new metropolis on the outskirts of the city.

- For example, in 2014, the illegal construction of a dam and hydropower station in a nationally designated poor country in the Shaanxi Province was publicized. This project was not based on an EIA or on the approval procedures from higher authorities. The planned inundated area covers the territory of a national wetland park inhabited by quite a few endangered species. The primary purpose of this project is not to generate electricity but to create human-made and dam-based scenery to facilitate the creation of a ‘waterscape city’ and the construction of water-based recreational facilities. See detailed information from Chen, X.W. A National Designated Poor Country in Shaanxi Province Spent Millions of Dollars to Build a Hydropower Station for Creating Human-Made and Dam-Based Scenery. Oriental Morning Post. 8 May 2014. Available online: http://news.163.com/14/0508/08/9RN89R4800014AED.html (accessed on 19 May 2019).

- The Ministry of Environmental Protection was replaced by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China according to the “Institutional Reform Plan for the State Council” approved by the 13th session of the National People’s Congress Conference in March 2018.

- Ministry of Environmental Protection, PRC. China’s Fourth National Report on the Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.P.; Luo, Y. The theoretical analysis on the legislative model of “One Reserve, One Enabling Act” in nature reserves at the national level. World For. Res. 2007, 20, 68–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- MoHURD. Bulletin of the Development of Scenic and Historic Areas in China (1982–2012). Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 3–4. Available online: http://www.mohrd.gov.cn/zxydt/w02012120419937414971793750.doc (accessed on 5 April 2019). (In Chinese)

- The State Council. “Report of the State Council on the Construction and Management of Protected Areas” [《国务院关于自然保护区建设和管理工作情况的报告》] was issued on 30 June 2016 and implemented on 30 June 2016.

- Tang, F.L.; Yan, Y.; Liu, W.G. Construction Progress of National Parks in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2019, 27, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- The “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Scenic Spot” [中华人民共和国风景名胜区管理条例] was issued on 6 September 2006 by the State Council and entered into practice on 1 December 2006.

- China Business Network (CBN). The Shortage of Funds for Protected Areas in China Became Worse. Shanghai. 3 March 2019. Available online: http://finance.eastmoney.com/a/201903031057966427.html (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Hu, X.L. Research on Public Participation in Environmental Decision-Making in the Internet+ Era; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Study on Legal System for Public Participation in Promoting Ecological Progress. Master’s Thesis, Environment and Resources Protection Law of Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Tian, B. Improvement of public participation system in the east dongting lake nature reserve. J. Wuling 2012, 37, 12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.M.; Wen, Z.G. Review and challenges of politicizes of environmental protection and sustainable development in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 3, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.L. Research on legal system of right protection of residents of nature reserves in China. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci.) 2012, 33, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Article 6 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) is similar with Article 6 of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version). Article 6 says “All units and individuals shall have the obligation to protect the environment. Local people’s governments at various levels shall be responsible for the environmental quality within areas under their jurisdiction. Enterprises, public institutions and any other producers/business operators shall prevent and reduce environmental pollution and ecological destruction, and shall bear the liability for their damage caused by them in accordance with the law. Citizens shall enhance environmental protection awareness, adopt low-carbon and energy-saving lifestyle, and conscientiously fulfill the obligation of environmental protection.” The “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (2014 version) [中华人民共和国环境保护法] was newly modified based on the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” (1989 version) on 24 April 2014 and entered into force on 1 January 2015.

- The “Decision by the State Council on Several Issues Concerning Environmental Protection” [国务院关于环境保护若干问题的决定] was issued on 3 August 1996. Although it is named as a ‘decision’, it is regarded as an important guideline for legislation and policy on environmental protection issues.

- Li, Y.F. The legal system for the public participation and environmental protection. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2004, 2, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Public Participation in Environmental Management from the Perspective of China. Discussion Papers in Social Responsibility. 2009. Available online: www.socialresponsibility.biz (accessed on 8 August 2012).

- The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention and Control of Pollution from Environmental Noise” [中华人民共和国噪声污染防治法] Was Issued on 29 October 1996 and Entered into Effect on 1 March 1997. Available online: http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?lib=law&id=544 (accessed on 9 August 2012).

- Wu, G. China in 2010: Dilemmas of “scientific development”. Asian Surv. 2010, 51, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q. Public participation and the challenges of environmental justice in China. In Environmental Law and Justice in Context; Ebbesson, J., Okowa, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Net. The First “Measures on Public Participation in Environmental Issues was Issued, it Strengthens Democracy in Decision-Making”. Beijing, China, 22 February 2006. Available online: http://env.people.com.cn/GB/1072/4130691.html (accessed on 10 October 2012).

- Ribot, J.C. Democratic Decentralization of Natural Resources: Institutionalizing Popular Participation; World Resource Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, W.; Wang, B.; Jones, P.J.S.; Axmacher, J.C. Challenges in developing China’s marine protected areas system. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Xu, S.S.W. Recent protected-area designation in China: An evaluation of administrative and statutory procedures. Geogr. J. 2004, 170, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The “Law on Environmental Impact Assessment of the People’s Republic of China” [中华人民共和国环境影响评价法] Was Adopted in 2012 and Entered into Effect on 1 September 2003. Available online: http://www.people.com.cn/GB/shehui/212/3572/3574/20021029/853043.html (accessed on 4 May 2012).

- Pengpai News. Five Hundred Green Peacocks Shut Down a Billion Hydropower pRojects? Both Sides of the Case Appeal, Environmental Impact Assessment Left Hidden Dangers. Shanghai. 8 May 2020. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/393832963_260616?spm=smpc.home.top-news2.6.1588943004583s0X6bqd&_f=index_news_5 (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Article 46 of the “Management Measures on the Special Marine Protected Areas” [海洋特别保护区管理办法] points out that “(…) the authority and the enterprise who explore the special marine protected areas shall sign a franchise agreement that the income should be devoted to conserve protected areas and give the compensation to rights holders. Due to accidents and emergencies in the special marine protected areas, any units and individuals that cause pollution and damage to the special marine protected areas must take timely measures to reduce or eliminate the impact on the ecology and resources of the special marine protected areas and restore the damaged marine landscape”.

- Bardhan, P. Decentralization of governance and development. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- In the late 1970s, there was an urgent need to draft China’s first environmental protection law(Trial), some legal scholars from Peking University and Chinese Academy of Social Sciences began to research environmental laws. In the early 1980s, Chinese Universities began to offer undergraduate courses on environmental laws. In the early 1990s, the academic degree committee of the State Council began to approve the granting of doctoral degrees in environmental law in Chinese Universities. See more details: Wang, J. The Chinese phenomenon of environmental law: Origin and future. Tsinghua Univ. Law J. 2018, 12, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- State Council, Announcement of the State Council on Further Strengthening the Management of Nature Reserves [国务院办公厅关于进一步加强自然保护区管理工作的通知], Guobanfa No. 111, 1998.

- Harkness, J. Recent trends in forestry and conservation of biodiversity in China. China Q. (Spec. Issue China’s Environ.) 1998, 156, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.Y. Management of marine nature reserves in China: A legal perspective. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2003, 6, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.B.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Fan, M. Current status and recent trends in financing China’s nature reserves. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Yuan, Ren(人) Min(民) Bi(币), Chinese Currency.

- Xu, H.G. Discussion on the funding policy of protected areas in China. Rural Ecol. Environ. 2001, 17, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. Report reveals that 26 billion yuan is needed per year to defend the bottom line of ecological safety. First Financial Daily. 9 November 2012. Available online: http://finacne.qq.com/a/20121109/000350.htm (accessed on 16 May 2018).

- In recent years, the percentage of the NPS budget in terms of the federal outlay is between around 0.08% and 0.1%. In China, the estimation of 27 billion covers every aspect of ecological protection in which PA funding only accounts for a very limited part. The overall outlay in 2012 was 125, 71 billion yuan in China. See Ministry of Finance, Financial Revenue and Expenditure in 2012. Available online: http://gks.mof.gov.cn/zhengfuxinxi-/tongjishuju/201301/t20130122_729462.html (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Sohu News. How to Obtain Stable and Reasonable Financial Security? On the Fund Guarantee Mechanism of National Parks in China. 24 October 2018. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/271054616_168681 (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Tao, S.M. Prospects for Protected Areas: From the Perspective of Historical Mission and Strategic for Survival; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S. Improve the law on the fund mechanism for protected areas in China. Xi’an Build. Univ. Sci. Technol. J. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2012, 6, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- The “Establishment Standards for Protected Areas Projects” was formulated by the forestry and grass bureau, jointly managed by the ministry of housing and urban rural development and the National Development and Reform Commission. It entered into practice on 1 December 2018.

- Wang, Q.D. Legal research on social charge for natural resources management in protected areas. Jurist 2008, 3, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- The “Management Methods on Special Funds Utilization for Protected Areas” (2001) [自然保护区专项资金使用管理办法] was issued by the Ministry of Finance on 5 December 2001. Available online: http://www.mof.gov.cn/zhengwuxinxi/caizhengwengao/caizhengbuwengao2002/caizhengbuwengao20021/200805/t20080519_21042.html (accessed on 2 September 2018).

- The “Standardization of Construction and Management Guidelines for National Protected Areas” (2009) [国家级自然保护区规范化建设和管理导则(试行)] was issued on 13 August 2009. Available online: http://www.zhb.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bh/201004/t20100409_187994.htm (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- Dan, G.; Song, Y.Q. Making central-local relations work: Comparing America and China environmental governance systems. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2007, 4, 418. [Google Scholar]

- Prof. Cai Shouqiu and Prof. Luo Ji hold different opinions on how to re-allocate the productive function of the SFA on the panel discussion during the Annual Conference of the Environmental and Nature Resource Law Society of 2014, held on 21–22 August in Guangzhou, China. Prof. Cai proposed that it is necessary to establish a state-owned enterprise that is responsible for timber production and Prof. Luo proposed for privatization of timber rights in China.

- For example, Wuyishan Protected Areas at the National Level is under the direct control of the Forestry Department of Fujian Province, instead of the government of Wuyishan City.

- Lv, Z.M. New thoughts on legislation of protected areas. Environ. Ecol. Netw. Environ. Prot. 2019, 3, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.W.; Yang, R. Discussion on some issues of the legislation for national parks and protected areas in China. Chin. Gard. 2016, 2, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, B.R. Reform of national parks system in China: Review and prospect. Biodivers. Sci. 2019, 27, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. Legal expression of the natural reserve system with national park as the main body. J. Jishou Univ. 2019, 5, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pimber, M.L.; Pretty, J.N. Passive participation’ means people participate by being told what is going to happen or what has already happened, but they have no opportunity to change them. Parks people and professionals: Putting “participation” into protected area management. In Social Change and Conservation: Environmental Politics and Impacts of National Parks and Protected Areas; Ghimire, K.B., Pimber, M.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.L. ‘Self-Mobilization Participation’ Means People Participate by Taking Initiatives Independent of External Institutions to Change Systems. The “Self-Mobilization Participation” Also Means All the Relevant Parties Actively Participate in the Whole Process and Take Their Possible Reasonable Responsibilities. The Community-based Management on Fishery in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The “Notification on Further to Strengthen Hydropower Construction and Environmental Protection” [关于进一步加强水电建设环境保护的通知] was issued on 6 January 2012 by the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China. This notification can be regarded as a policy, but it helps to forbid some economic activities in protected areas in China.

- Xinhua Net. The department of environmental protection response to environmental groups events: It is rule of development. Posted on 12 November 2012.

- Lang, H.L. As for analysis of the public participation provisions in the new EPL, Public participation in environmental decision-making in China: Towards an ecosystem approach. Int. Biodeterior. 2014, 95, 356–363. [Google Scholar]

- “Government oriented, common participation” means the government play a leading role in protected areas establishment and management and local peoples, experts, enterprises, social organizations are also invited to actively participate in the whole progress of national parks establishment and management.

- The “Hubei Xingdoushan National Nature Reserve Management Regulation in Enshi Tujia and Miao autonomous prefecture” was issued on 30 July 2010.

- Conservation, Human Rights & Protected Areas Governance: A field-Based Workshop in the Baviaanskloof Mega-Reserve. South Africa. 6–7 July 2007. Available online: http://cmsdata.iucn.org/downloads/bav_workshop.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2012).

- Tang, F.L. Thoughts on the system construction of national parks with Chinese characteristics. For. Constr. 2018, 5, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- The pilot reform plan of the Sanjiangyuan national park system was examined and approved at the central level at the end of 2015. Since then, China’s first national park pilot program was officially launched.

- Zhuang, Y.B.; Yang, R.; Zhao, Z.C. Preliminary analysis on the implementation plans for the Chinese national park pilot areas, China. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 33, 5–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zero draft of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. In Proceedings of the Open-Ended Working Group on the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework Second Meeting, Kunming, China, 24–29 January 2020. CBD/WG2020/2/3.

| Main Class | Subclass | Type | Objectives of Protection and Targets for Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Protection | National Parks | National Parks | To protect natural ecosystems in special land or sea areas that represent the State in the strictest intensity and to ensure the scientific protection and rational utilization of natural resources |

| Original Protected Areas | To protect natural ecosystems, rare and endangered species of wild animals and plants in natural concentrated distribution areas and natural relics with special significance and other objects of protection in the land, land water or sea | ||

| Natural Protected Areas | Marine Protected Areas (excluding Marine Parks) | To protect sea areas and islands with important marine interests and special hydrodynamic conditions, to protect marine biodiversity and ecosystem services, to protect marine biological resources, mineral resources, oil and gas resources and marine energy resources and to promote sustainable utilization of marine resources | |

| Protection Zones of Aquatic Germplasm Resources | To protect aquatic germplasm resources and their living environment (e.g., the main production and reproduction areas, including waters, beaches and adjacent islands, land, etc.) | ||

| Natural Small Protected Areas | To protect relatively intact natural ecosystems or wildlife, ancient and famous trees, rare and endangered species and precious genetic resources with important values in small areas that are outside the traditional protected areas | ||

| Restricted Utilization | Landscape and Famous Scenery | Scenic Spots | To protect and make rational use of the natural resources in landscape and famous scenery with ornamental, cultural or scientific value, and to realize scientific planning, unified management, strict protection and sustainable use |

| Forest Parks | To make rational use of forest scenic resources and to develop forest tourism | ||

| Geological Parks | To protect the geological relic resources with special geological significance and high aesthetic values and to promote the sustainable development of the social economy | ||

| Natural Parks | Wetlands Parks | To protect the ecosystems in wetlands, to make rational use of wetland resources and to carry out wetland publicity, education and scientific research | |

| Marine Parks | To protect the ecosystems and the historical and cultural value in marine parks | ||

| Desert Parks | To protect the ecosystems and the ecological functions in desert parks and to make rational use of natural and cultural landscape resources, and to carry out some important activities such as ecological protection, vegetation restoration, scientific research monitoring, publicity and education and ecological tourism | ||

| Sustainable Use | Ornamental Recreation | Water Recreation Areas | To protect water and scenic resources, to improve the environment, to achieve the balance among social benefits, environmental benefits and economic benefits and to achieve harmony between humans and nature |

| Resources Benefits | National Natural Forests | To protect the forests formed by natural formation and artificial promotion of natural regeneration or germination, to maintain and improve the ecological environment to meet the demand of social and national economic development for forest products | |

| National Public Welfare Forests | To protect the forest land that provides public welfare and social products or services, to maintain and to improve the environment, to maintain ecological balance, to protect biological diversity and to meet the requirements of the ecological and social needs of humans and sustainable development |

| Law | Article No. | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Laws on Endangered Species | ||

| Law on the Wildlife Protection of the People’s Republic of China [29] | Article 12 | (…) The people’s governments at or above the provincial level shall delimit relevant nature reserves in accordance with the law to conserve wildlife and their important habitats and protect, restore and improve the living environment of wildlife. Where the conditions for the delimitation of relevant nature reserves are not met, the people’s governments at or above the county level may conserve wildlife and their habitats by delimiting no-hunting (or no-fishing) zones or prescribing closed hunting (or fishing) seasons or other means. Human disturbances threatening the living and breeding of wildlife, such as introducing alien species into relevant nature reserves, creating pure forests, and excessively spraying pesticides, shall be prohibited or restricted. The relevant nature reserves shall be delimited and administered in accordance with the provisions of relevant laws and regulations. |

| Article 13 | (...) It shall be prohibited to construct, in relevant nature reserves, any projects which are not allowed to be constructed under relevant law and regulations. (...) | |

| Article 20 | It shall be prohibited to hunt or catch wildlife or otherwise disturb the living and breeding of wildlife within the relevant nature reserves and the no-hunting (or no-fishing) zones or during the closed hunting (or fishing) seasons, except as otherwise specified by laws and regulations. (...) | |

| Article 45 | Whoever, in violation of Article 20, Article 21, paragraph 1 of Article 23, or paragraph 1 of Article 24, hunts or catches any wildlife under state priority conservation in a relevant nature reserve or a no-hunting (or no-fishing) zone or during a closed hunting (or fishing) season, hunts, catches, or kills any wildlife under state priority conservation without a special hunting or catching permit or against the requirements of a special hunting or catching permit, or hunts or catches any wildlife under state priority conservation with a prohibited tool or by a prohibited means shall be fined not less than two nor more than ten times the value of the catch or if there is no catch, be fined not less than 10,000 yuan nor more than 50,000 yuan by the competent department of wildlife conservation of the people’s government at or above the county level, the oceanic law enforcement department, or the administrative authority of the relevant reserve according to the division of their functions, with the catch, the hunting or catching tool, and all illegal income confiscated and the special hunting or catching permit revoked; and if the violation is criminally punishable, the offender shall be held criminally liable in accordance with the law. | |

| Law on the Wild Plants Protection of the People’s Republic of China [30] | Article 2 | (…) As regards the protection of medicinal wild plants and wild plants within urban gardens, nature reserves and scenic spots, other relevant laws and regulations shall be also applied. |

| Article 11 | Districts with a natural concentrated distribution of species of wild plants under special state or local protection shall be designated as nature reserves in accordance with relevant laws and regulations; (…). | |

| Laws on Natural Resources | ||

| Forest Law of the People’s Republic of China [31] | Article 24 | (…) Serious protection should be given to rare and precious trees outside nature reserves and plant resources with special value in forest regions; it is forbidden to cut or collect any plants resources without the approval of the competent department of forestry of the provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the Central Government. |

| Mineral Resources Law of the People’s Republic of China [32] | Article 20 | Unless approved by the competent departments authorized by the State Council, no one may mine mineral resources in the following places: … (5) nature reserves and important scenic spots designated by the State, major sites of immovable historical relics and places of historical interest and scenic beauty that are under State protection; and (6) other areas where mineral mining is prohibited by the State. |

| Law on the Special Marine Protected Areas | ||

| Management Measures on the Special Marine Protected Areas [33] | Article 13 | (…) Before submitting the approval of establishing special marine protected areas, the authority who submits to the approval shall inform the public and let the public give some suggestions and comments. |

| Article 17 | After establishing special marine protected areas, the management authority shall build some landmarks and signs in some appropriate places according to their boundaries, the authority also shall publish management rules, measures and other relevant information on special marine protected areas. | |

| Article 28 | The administrative agency of marine special protected areas shall organize units and individuals within the areas to participate in the construction and management of marine special protected areas, cooperate local communities to participate in the co-management and protection of marine special protected areas, and jointly formulate plans for cooperative projects, community development plans, general plans and management plans within the areas. | |

| Article 46 | (…) the authority and the enterprises who explore the special marine protected areas shall sign a franchise agreement that the income should be devoted to conserve protected areas and give the compensation to rights holders (…) | |

| Laws on Preventing Pollution | ||

| Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention of Pollution Damage to the Marine Environment by Land-sourced Pollution [34] | Article 8 | No organization or individual may establish outlets for discharging sewage within special marine reserves, marine nature reserves, seashore scenic and tourist areas, salt works reserves, bathing beaches, important fishing areas and other areas which need special protection. Those outlets already established within these areas stipulated in the preceding paragraph, where the discharge of pollutants is in excess of the national or local discharge standards, shall be improved within a prescribed period of time. |

| Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention of Environmental Pollution Caused by Solid Waste [35] | Article 22 | It shall be forbidden to construct facilities or sites for the centralized storage and disposal of industrial solid waste or burial site for residential refuse in nature reserves, scenic spots, historic sites, drinking water sources, and other places of special protection designated by the State Council and the people’s governments at the provincial, municipal or autonomous regional levels. |

| Law of the People’s Republic of China on Prevention and Control of Desertification [36] | Article 22 | (…) The local people’s government at or above the county level shall make plans to help the farmers and herdsmen living in the enclosed and forbidden reserves of desertified land move out of the areas and settle down appropriately. With regards to production and everyday life of the farmers and herdsmen still living in the enclosed and forbidden reserves of desertified land, the authority there shall make proper arrangements for them. Without approval of the State Council or the authority designated by the State Council, no railways, highways, etc. may be constructed in enclosed and forbidden reserves of desertified land. |

| Prior Fields No. | Contents |

|---|---|

| Prior Fields 1 | To improve the policy and legal system for biodiversity conservation and sustainable utilization |

| Prior Fields 2 | To integrate biodiversity conservation into sectoral and regional planning to promote sustainable use |

| Prior Fields 3 | To carry out biodiversity survey, assessment and monitoring |

| Prior Fields 4 | To strengthen in-situ protection for biodiversity |

| Prior Fields 5 | To scientifically adopt ex-situ protection for biodiversity |

| Prior Fields 6 | To promote rational utilization and benefit sharing of biological genetic resources and the related traditional knowledge |

| Prior Fields 7 | To strengthen the safety management for invasive alien species and genetically modified organisms |

| Prior Fields 8 | To enhance our capacity to respond to climate change |

| Prior Fields 9 | To strengthen scientific research and talent training in the field of biodiversity |

| Prior Fields 10 | To establish public participation mechanisms and partnerships for biodiversity conservation |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, M.; Cliquet, A. Challenges for Protected Areas Management in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155879

He M, Cliquet A. Challenges for Protected Areas Management in China. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155879

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Miao, and An Cliquet. 2020. "Challenges for Protected Areas Management in China" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155879

APA StyleHe, M., & Cliquet, A. (2020). Challenges for Protected Areas Management in China. Sustainability, 12(15), 5879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155879