1. Introduction

Sustainable tourism development requires a balance between several dimensions—environmental, economic, and socio-cultural—as well as the participation of all the agents and actors (governments, business and stakeholders) to achieve long-term sustainability. In terms of worldwide economies, most businesses have used linear production models based on production and consumption. These business models have negative impacts on the environment such as CO

2 emissions, global warming, damage to natural and non-renewable resources, pollution, high energy resources and waste [

1]. The environmental perspective requires that companies improve their production models, such as minimizing the consumption of resources in order to increase competitiveness with a focus on sustainability, and adopting new business models such as circular economy models [

2,

3,

4].

The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) proposes four main areas to promote sustainable business in the tourism industry: effective planning for sustainability, maximizing social and economic benefits for the local community, to promote cultural heritage, and to avoid negative impacts on the environment (GSCT, 2020). The criteria are established as minimum levels to achieve best practices in sustainable tourism, and these criteria are developed through a set of criteria, indicators and guidelines [

5]. The analysis of business efficiency is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals SDG (Goal 12—responsible production and consumption). The use of fewer inputs or resources to obtain a better efficiency with a sustainable perspective is crucial for future business models in tourism industry.

Efficiency is an economic concept related to the scarcity of available resources, which is susceptible to alternative uses. In the previous literature, efficiency has been linked to productive activity, by relating inputs or resources and outputs or production. However, the term business efficiency is more extensive than productive efficiency, and implies a relationship between inputs or economic resources, expressed both in physical and monetary units, and outputs expressed as economic results of the company, both in physical units and monetary value (income, costs, benefits, etc.). Furthermore, the efficiency index is a relative index: a company or decision-making unit is more or less efficient according to the sample of firms analyzed [

6,

7].

There is extensive efficiency research on the hotel industry focusing on how well firms manage their resources. In the last decade, the academic literature has made notable progress in overcoming the main weaknesses of early efficiency studies, mostly related to scope (only one objective, efficiency measure), setting (a single city, region or destination), period (only one year), methodology (one-stage Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) or performance models), sample size (small samples with few observations), available data (few variables selected for inputs and outputs as well as potential drivers of efficiency) and industries (most empirical tourism research examines hotel firms).

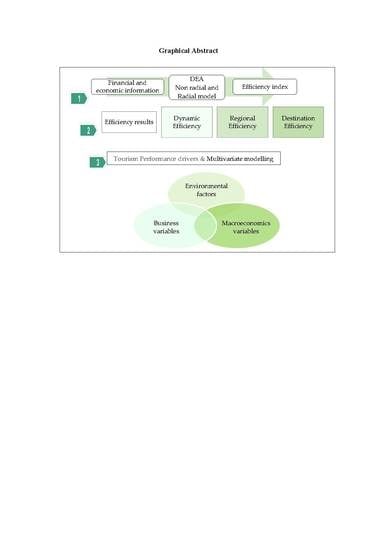

Our study aims to contribute to the substantial efficiency literature in several ways. The study offers evidence on a tourism sector that has not been widely explored to date: holiday and other short-stay accommodation (the classification includes the provision of accommodation, typically on a daily or weekly basis, principally for short stays by visitors, in a self-contained space consisting of complete furnished rooms or areas for living/dining and sleeping, with cooking facilities or fully equipped kitchens. This may take the form of apartments in small, free-standing, multi-storey buildings or clusters, single-storey bungalows, chalets, cottages and cabins). The evidence on new industries responds to recent calls for research on new contexts and industries [

8]. To overcome the problem of micro-samples and cross-sectional data, the study uses 12,864 firm-level observations during the period 2005–2016. We used radial and non-radial DEA models to assess tourism firm efficiency. The non-parametric frontier analysis DEA covers a large set of theoretical and empirical tourism research papers based on the original Farrell model [

9] to measure efficiency. In fact, DEA is a nonparametric technique for frontier analysis that has been widely used to measure efficiency in tourism firms by means of a comparative synthetic index [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The results of the study are analysed by year, regional location and destination type. The analysis by year allows us to understand the evolution of the efficiency over the period (it should be noted that the period includes the pre-2008 financial crisis years, the years affected by the 2008 financial crisis and post-2008 financial crisis years). It is also interesting to show the results by regional location because most related empirical studies find that location is a source of competitive advantage for tourism firms and the tourist accommodation sector [

10,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The current study also proposes a range of tourist destination dimensions in order to better analyse the efficiency of the industry. Our paper is the first to examine a wide variety of destination types (diversified and non-diversified tourism), thereby contributing new insights to the existing literature. The results of this research are particularly interesting in terms of the tourist non-diversified destinations: (i) sun-and-sea, (ii) cultural, and (iii) rural tourism, as well as diversified/mixed destinations that combine dimensions, such as (i) cultural and sea tourism; (ii) cultural and rural tourism; (iii) sea and rural tourism; (iv) snow and mountain tourism; (v) wine and rural tourism.

Another interesting question concerns the factors that boost efficiency. The short-stay accommodation industry is a subsector with a clear prevalence of micro-firms (fewer than 10 persons employed). Micro-firm characteristics such as governance, ownership, agency problems, strategies and access to external funds, differ from large firms. Traditional drivers of efficiency in the hotel industry (size, location, tourist attraction) and ongoing drivers proposed by the recent literature (environmental variables and other business factors) can show similar behaviours in the holiday and short-stay accommodation industry or a different picture. To explore this issue, we run both Tobit regressions and bootstrapped regressions to test the association among efficiency scores and business, environmental and macroeconomic variables. Specifically, the current study examines factors such as firm size, legal form, leverage, cash flow, 2008 financial crisis, tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay.

Finally, given recent calls for robust research applying methodological advances, we use an additional DEA model to assess efficiency and its potential drivers. That is, we combine more advanced methods such as the non-radial with radial DEA models to confirm the previous results. By using several DEA approaches, the study provides further evidence and contributes to a better understanding of efficient firm management as well as confirming the drivers of that efficiency.

The dynamic efficiency results confirm the impact of the financial crisis (2008–2011) on tourism firms. The results also indicate that firms geographically located in diversified destinations that combine cultural and rural dimensions (cultural and sea tourism, cultural and rural tourism, sea and rural tourism, snow and mountain tourism, and wine and rural tourism) perform better than those located in non-diversified destinations such as: (i) only sun-and-sea tourism, (ii) only cultural tourism, and (iii) only rural tourism. Considering regional efficiency, the most efficient firms are located in the Basque country, Catalonia, La Rioja, Madrid and the Canary Islands.

The results also show that factors such as legal form, cash flow, tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay are positive and significantly associated with efficiency score, whereas factors such as the 2008 financial crisis, firm size and leverage are negative and significantly associated with efficiency score. However, the variable legal form needs further examination in future research, as most of the firms in the sample belong to the same category. It should be also noted that the most representative firm size segment is micro-firms. The evidence shows that the highest levels of efficiency are achieved by micro-firms and large firms. Furthermore, the Tobit and bootstrap regressions also confirm the association between the efficiency score and firm determinants: business, environmental and macroeconomic variables.

A novel contribution of this study to the previous literature is the industry under analysis—short-stay tourist accommodation—in conjunction with the segmentation by tourist destinations associated with the firms’ geographical locations (diversified and non-diversified tourism; including some tourism dimensions such as rural, cultural and wine tourism), as well as the application of several methodologies and sensitivity analyses to confirm the results. This study provides important evidence for decision-makers, entrepreneurs and tourism policymakers seeking to define the behaviour of the most efficient companies by regions and tourist destinations. It also confirms that the diversification of the tourist destinations based on cultural and rural tourism dimensions is a useful strategy for improving economic growth, competitiveness and tourist firms’ performance.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: the next section reviews the existing literature.

Section 3 explains the methodology, business, macroeconomics and environmental variables used in the empirical analysis, as well as the sample and descriptive statistics for all the models.

Section 4 presents the empirical results and includes supplemental analyses.

Section 5 and

Section 6 present the discussion and the conclusions, and finally the last section focuses on the limitations and future developments.

2. Literature Review

A matter of considerable interest in production theory and tourism growth is the assessment of performance and efficiency. The main body of the tourism and efficiency literature [

13,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] has primarily applied non-parametric frontier analysis methodologies such as the DEA model to evaluate the competitiveness and efficiency of firms. This methodology allows the researcher to estimate a synthetic index through a set of input and output variables, and with several DEA model specifications.

Liu et al. [

28] review the main areas for the application of DEA in recent years and point out that the “two-stage contextual factor evaluation framework” is the prevailing trend. In the tourism industry, location has been considered a key factor for boosting economic growth, competitiveness and efficiency. There is extensive research focusing on location as source of competitive advantage for tourism firms.

Previous studies have analyzed the tourist destination variables as a factor linked to geographical location. For example, Botti et al. [

29] compare the competitiveness of tourist destinations considering 22 French regions. The study focuses on regional performance from a geographical perspective. Their model identifies the best regional practices as well as the possibility of improving efficiency in the 12 regions analysed. Ben Aissa and Goaied [

13] focus on the competitiveness of Tunisian tourist destinations from a regional perspective, and the influence of macroeconomic variables, namely, investment, economic circumstances, number of travel agents and worker skills. Other studies analyse economic growth, competitiveness and regional efficiency focusing on cultural tourism [

30]; specifically, such studies aim to link cultural resources and tourist demand, by including a production function and the region’s available cultural resources.

More recent studies assess the impact of tourist destination on firm efficiency, focusing on tourist location. Lado-Sestayo and Fernández-Castro [

24] classify the location at the tourist destination level instead of tourist regions. Our research expands on the previous literature focusing on tourist destination variables by including geographical location (regional location) and tourist destinations type: non-diversified destinations such as (i) sun-and-sea tourism, (ii) rural tourism, and (iii) cultural tourism), and diversified tourism destinations (based on several tourism dimensions such as rural, cultural and wine tourism): (i) cultural and sea tourism; (ii) cultural and rural tourism; (iii) sea and rural tourism; (iv) snow and mountain tourism; (v) wine and rural tourism. The empirical literature has also tested the relationship between firm efficiency and a wide range of business variables such as firm size [

8,

10,

17,

20,

21,

31], management styles and ownership types [

12,

16,

17,

20,

31,

32], type of service [

8], firm age [

16,

20], professional specialization [

33], and corporate governance variables [

34,

35], among others.

For example, Barros [

10] found evidence that firm size and location are positively associated with firm efficiency in a sample of Portuguese hotels. Barros and Dieke [

32] examined the efficiency of 12 Luanda hotels for the years 2000–2006. In a second stage, they ran a bootstrap regression to test the relationship between hotel efficiency and market share, hotels belonging to a commercial group and hotels with an international expansion strategy. Shang et al. [

16] examined the efficiency in international tourist hotels in Taiwan and the efficiency drivers using Tobit regressions and bootstrap regressions. The results indicate that firm efficiency is influenced by location (they compare resort hotels and metropolitan area hotels) and firm age. Conversely, management style and e-commerce are not associated with firm efficiency. Parte and Alberca [

12] show that market conditions and business factors such as ownership structure and audit variables are associated with efficiency scores.

Assaf and Agbola [

20] examined technical efficiency in Australian hotels during the period 2004–2007 using a DEA double bootstrap approach. They found that location, firm size, star rating and age are drivers of greater efficiency. In another paper, Assaf et al. [

17] evaluated firm-level determinants of efficiency in 78 Taiwanese hotels during the period from 2004 to 2008 using a bootstrap model. The results reveal that firm size, type of organization (chain or independent hotels), and the type of tourist (international tourist class or tourist class hotels) are positively associated with firm efficiency. Moreover, Assaf and Tsionas [

8] examined 613 hotels operating in different locations worldwide and found that location (urban, airport, suburban, interstate, small metro/town and resort) and type of service (full vs. limited) are drivers of firm efficiency. Regarding firm size, the study shows that this factor is not important in boosting firm efficiency.

Regional-level efficiency analysis has also attracted the attention of academia [

22,

24,

25,

26,

29,

36,

37,

38]. Generally, prior studies use DEA methodology to measure efficiency in a first stage, and Tobit or bootstrap models to test the association between the efficiency level and its potential determinants in a second stage. For example, Botti et al. [

29] examined regional efficiency in France and found that the number of tourists is a driver of efficiency. Barros et al. [

36] also focused on regional efficiency in France, showing in the second-stage analysis that efficiency scores are associated with the number of monuments, number of museums, number of theme parks, kilometres of beaches, presence of ski resorts, and presence of natural parks. Huang et al. [

37] examined the Chinese industry and included factors such as the richness of tourism resources, international tourism attractiveness (ratio of inbound arrivals to total inbound arrivals in China), education (proportion of urban employees with senior high school education or higher), payment levels of employees, market competition and regional trade openness.

Focusing on the hotel industry in Spain, Solana-Ibáñez et al. [

22] examined variables such as coastal destination, number of cultural sites, number of museums and collections, meeting attendance, number of federated golf clubs, number of restaurants and number of retailers. To obtain robust results, they used two-stage double bootstrap DEA. Sellers-Rubio and Casado-Díaz [

25] find that the length of stay and tourist arrivals are strong drivers of firm efficiency. Lado-Sestayo and Fernández-Castro [

24] used a sample of 400 hotels in 97 tourist destinations in Spain. In the second stage, they included factors related to destination (accessibility, population density, market concentration, occupancy, demand and seasonality) and management factors (size, market orientation or meeting space capacity, market share, number of stars, management agreements and distance to the tourist destination). The results show the importance of tourist destination variables for firm efficiency.

Yang et al. [

38] focused on regional efficiency in the Chinese hotel industry using a super-efficiency slack-based measure in DEA. The findings suggest that room price and occupancy rate are the main determinants of firm efficiency. Chaabouni [

26] examined 31 Chinese provinces during the period 2008–2013 using a two-stage double bootstrap approach. He found that trade openness, climate change and the intensity of market competition all boost tourism efficiency. To gain an understanding of the potential determinants of hotel performance, Assaf et al. [

17] conducted an extended analysis with more than 20 variables. The results show that the quality of the educational system, government support, disposable income, and number of international arrivals to a tourism destination are key factors in firm performance.

In terms of sustainability, Kularatne et al. [

26] focused on the efficiency in hotels environmentally sustainable in Sri Lanka for the period 2010–2014. The eco-friendly practices were measured through three variables: energy-saving, water-saving and waste management practices. The evidence shows that hotels that are environmentally responsible in terms of improving energy competitiveness and waste management achieve more efficiency compared to the remaining hotels. In contrast, water consumption does not present the result expected. Radovanov et al. [

4] evaluated the sustainable tourism development efficiency, using a DEA model in a sample of 27 EU countries and five Western Balkan countries over the period from 2011 to 2017. The results show a positive and significant association between tourism efficiency and factors such as sustainability of tourism development, share of GDP and tourist arrivals and inbound receipts. In contrast, government expenditure on tourism is negatively and significantly associated with tourism efficiency.

The review of the literature points to the remarkable progress made in the study of efficiency determinants over the last decade; however, there are still calls in academia for a better understanding of efficiency determinants [

33,

38,

39]. Yang et al. [

38] argue that it is crucial to introduce industry factors as well as local factors in the evaluation of efficiency.

It is important to highlight that the related tourism research has primarily focused on hotel firms, with little evidence reported for other subsectors such as the holiday and short-stay accommodation industry. To fill this gap, this study provides empirical evidence to contribute to a better understanding of this subsector. Moreover, this study deals with the efficiency of tourist destinations competitiveness, combining several dimensions such as geographical location and diversification level of tourism destination based on some tourism dimensions such as rural, cultural and wine tourism. These classifications and segmentations have not been analysed in previous efficiency studies.

4. Empirical Results

The empirical results of the first and the second methodological stages are shown in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2, respectively.

Section 4.1 presents the first-stage results: the efficiency results of tourism firms (hostels and tourist apartments) by year, region and tourist destination.

Section 4.2 presents the second stage results: the association between the efficiency scores and contextual factors (business, macroeconomic and environmental variables) using correlation analysis, non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal Wallis test), and multivariate models such as Tobit and bootstrapped regressions. The subsection concludes with a Robustness analysis.

4.1. First Stage Results: Dynamic Efficiency Results, Regional Efficiency Results and Efficiency Results by Tourist Destination

This section summarizes the efficiency results in relation to three dimensions: year, regional location and tourist destination (diversified and non-diversified).

The results of the efficiency index by year for tourism firms (

Table 5 last row “Total”) reveal some variations over the period: in the pre-2008 financial crisis period (2005–2007) and the post-2008 financial crisis period (2012–2016), the efficiency indexes increase.

For example, in 2005, the efficiency index (

Table 5, average efficiency on the last row “Total”) was 0.499 and the average efficiency in 2007 period was 0.544; however, in the years affected by the 2008 financial crisis (2008–2011) some variations in average efficiency are observed. On average, the highest levels of efficiency are registered in the years 2007, 2010 and 2014, and the lowest in 2008 and 2011 (

Table 5, average efficiency on the last row “Total”). The Kruskal Wallis test (results not reported for brevity) shows statistically significant differences for the period analysed (

p < 0.05).

Figure 1 shows the tourist destinations according to two dimensions: non-diversified destinations (sun-and-sea tourism, rural tourism, and cultural tourism) and diversified destinations (specifically, cultural and sea tourism; Camino de Santiago, cultural and rural tourism; sea and rural tourism; snow and mountain tourism; and finally wine and rural tourism). The efficiency results by tourist destination types indicate that the most efficient tourism destinations correspond to mixed or diversified destinations based on some tourism dimensions such as rural, cultural and wine tourism; for example, those that combine cultural and sea dimensions, and those that combine the rural dimension with wine tourism. In contrast, the lowest ranked are the snow and mountain tourism destinations, and the Camino de Santiago, cultural and rural tourism destinations.

Table 6 shows the non-parametric analysis (Kruskal Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U test) to confirm the above efficiency results by tourist destination. The Kruskal Wallis test (

Table 6) indicates statistically significant differences (

p < 0.05) for the eight tourist destinations’ classification (sun and sea tourism, cultural tourism, rural tourism, snow and mountain tourism, Camino de Santiago, cultural and rural, cultural and sea tourism, wine tourism and rural tourism, sea tourism and rural tourism). The Mann–Whitney U test (

Table 7) indicates statistically significant differences for diversified and non-diversified tourism destinations (

p < 0.05).

The efficiency results (

Table 7, column “Mean efficiency”) indicate that diversified destinations (efficiency mean score = 0.5269) perform better than non-diversified destinations on efficiency (mean score = 0.5037).

An important novelty of this study is that it expands the efficiency results by region, including the variable tourist destination type, which indicates the type of tourism associated with the geographical location of tourism firms. Most previous research in the field shows that hotel efficiency is strongly associated with geographical location [

10,

16,

17,

20,

22,

24,

31]. In the empirical framework of this study, the regions registering the highest efficiency on average are the Basque country, Valencia, Catalonia, La Rioja and Madrid. In contrast, regions such as Extremadura occupy the bottom positions. The Kruskal Wallis test reveals statistically significant differences for regions (

p < 0.05).

Figure 2 presents the efficiency results by regional location of tourism firms. When the results are analysed by regions and tourist destinations types, the Valencia, Catalonia, Asturias and Canary Islands achieve the top positions in non-diversified destinations such as sun-and-sea tourism; Madrid and Cantabria achieve high efficiency levels in cultural tourism. Conversely, the results by diversified destinations indicate that Basque country and Catalonia achieve the top positions in diversified destinations based on rural, cultural and wine tourism dimensions, for example, destinations that combines cultural and sea tourism, the Canary islands achieve high efficiency levels in destinations that combine sea and rural tourism, and La Rioja ranks top in wine and rural tourism.

4.2. Second Stage Results: The Influence of Contextual Factors (Environmental Variables, Business Variables and Macroeconomic Factors)

The second methodological stage focuses on the association between the efficiency scores and the influence of contextual factors (business, macroeconomic and environmental variables). Firstly, we use several statistics or exploratory test (Spearman’s rank correlation, Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal Wallis test), and secondly we use more advanced multivariate models such as Tobit regression and bootstrapped regression. Specifically, in the second stage, we include eight factors in the exploratory test and the regression models to analyse the influence of contextual variables: the 2008 financial crisis as a macroeconomic factor, firm size, legal form, cash flow and leverage as business factors, and finally the arrivals of international tourist, overnight stays and average stay as environmental variables. Finally, we conclude the second methodological stage by using a VRS radial DEA model to confirm the above efficiency results and potential efficiency drivers.

Firstly, the

Table 8 presents the Spearman’s rank correlation. This correlation analysis helps to explore the association between the efficiency score and the contextual factors.

The correlation between efficiency score and environmental variables is positively and statistically significant: tourist arrivals (r = 0.023,

p < 0.05), overnight stays (r = 0.026,

p < 0.05), and average stay (r = 0.017,

p < 0.05). Similar results have been found for hotel firms [

11,

12,

24].

Table 8 also presents the correlation between efficiency scores and the macroeconomic factors (2008 financial crisis). This correlation is negative and statistically significant (r = −0.057,

p < 0.005). Finally, regarding business variables (legal form, cash flow or CFO, size and leverage),

Table 5 presents the correlation between efficiency score and business variables. The correlation between efficiency scores and legal form is positive and statistically significant (r = 0.116,

p < 0.05), as well as the correlation between efficiency score and cash flow (r = 0.203,

p < 0.05). In contrast, the efficiency score is negatively associated with size (r = −0.269,

p < 0.05) and leverage (r = −0.153,

p < 0.05). Previous empirical papers have also found that large firms do not always outperform second- and third-tier firms (see, for example [

8,

19]).

Additionally, we apply the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal Wallis test (see

Table A1,

Appendix A) to show if there are differences in efficiency score by contextual factors. The Kruskal Wallis test shows statistically significant differences for size (

p < 0.05) and legal form (

p < 0.05) and the Mann–Whitney U test reveals statistically significant differences for financial crisis (

p < 0.05). Regarding the size variable, the results show the highest efficiency for firms with fewer than five employees and firms with more than 20 employees. Considering the legal form, permanent establishments owned by non-resident entities and LLC achieve higher efficiency, on average, than other types of firms, such as foreign entities. Finally, the efficiency is lower, on average, during years affected by the 2008 financial crisis (2008–2011) than in the pre-2008 financial crisis and the post-2008 financial crisis periods.

The determinants of firm efficiency are analysed using Tobit regression models and bootstrap regression models. In order to deal with multicollinearity, we run several regressions including environmental variables in separate models.

The regression models show that efficiency scores are positively and statistically significantly associated with business variables such as legal form and cash flows, whereas efficiency scores are negatively and statistically significant associated with macroeconomic factors such as the 2008 financial crisis and other business variables such as size and leverage. In terms of environmental variables,

Table 9 and

Table 10 reveal that efficiency scores are positively and statistically significantly associated with environmental variables such as tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay. Consequently, both the Tobit and bootstrap regressions models show that the business variables, macroeconomic factors and environmental variables examined in this paper can be considered as drivers or variables that influence firm efficiency in the holiday and short-stay accommodation sector.

In this subsection, we conducted a robustness analysis to validate and confirm the previous results considering both the new dependent variable (efficiency scores with a new radial DEA model) and independent variables or contextual variables that could influence firm efficiency (the same contextual variables and also alternative measures). We applied the DEA radial model with variable returns to scale proposed by Banker et al. [

55] to obtain the efficiency results with a new model, and we repeated the second stage analysis to confirm the results for factors that could influence firm efficiency (environmental variables, macroeconomic factors and business variables). The radial DEA model was developed in a seminal paper by Charnes et al. [

40], in which the authors evaluated the Debreu–Farrell measure with the constant returns to scale (CRS) hypothesis. Banker et al. [

55] extended this original DEA model, proposing the BCC model with variable returns to scale.

As in the previous section, the BCC radial model results show that the years 2007, 2010 and 2014 register the highest levels of efficiency, while the years 2008 and 2011 present the lowest levels. The Kruskal Wallis test confirms statistically significant differences for years (p < 0.05), for tourist destination profile, for regions (p < 0.05) and for tourist destination (p < 0.05). Results are not reported for brevity.

The Spearman’s rank correlation also confirms previous results. The efficiency score has a significant and positive correlation with environmental variables such as tourist arrivals (r = 0.019, p < 0.05), overnight stays (r = 0.021, p < 0.05), and average stay (r = 0.028, p < 0.05), and business variables such as legal form (r = 0.10, p < 0.05) and cash flow (r = 0.029, p < 0.05). In contrast, the correlations are negative and statistically significant with size (−0.52, p < 0.05) and leverage (r = −0.104, p < 0.05). The Kruskal Wallis test also confirms statistically significant differences for business factors: size (p < 0.05) and legal form (p < 0.05). The Tobit regression and bootstrap regressions indicate that efficiency is positively associated with legal form, cash flow, tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay, while efficiency scores are negatively associated with size and leverage. The coefficients are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Results are not reported for brevity.

Second, we used alternative proxies for the independent variable to test the results presented in the previous section. In particular, we used different classifications for legal form because is not equally distributed among the sample, and alternative proxies for independent variables. The Kruskal Wallis test, Spearman correlation and regression analysis remain similar.

5. Discussion

This section discusses the results of this study and the similarities and differences with other previous results on the efficiency tourism field. Firstly, we comment on the efficiency results by year, region and tourism destination, secondly, the influence of environmental variables, business variables and macroeconomic factors on efficiency scores (or the efficiency drivers), and finally we present some comparisons with the prior efficiency literature.

Dynamic efficiency results by year indicate that the 2008 financial crisis (2008–2011) affected the tourism companies analysed, with average efficiency scores lower than in the pre-2008 financial crisis period (2005–2007) and the post-2008 financial crisis period (2012–2016). An important novelty of this study is that it expands the efficiency results by regional location, including the tourist destination (non-diversified and diversified) which indicates the type of tourism associated with the geographical location of the tourism firms. The dynamic efficiency results by tourist destination type (non-diversified and diversified) indicate that diversified destinations achieve higher efficiency levels than non-diversified destinations.

Focusing on non-diversified destinations, the main results indicate that Cantabria and Madrid are the top-ranked regions for some tourism dimensions, such as cultural tourism; Catalonia, Valencia and the Canary Islands obtain better efficiency results in sun-and-sea tourism and rural tourism. Conversely, efficiency results by diversified/mixed destinations indicate that the Basque country and Catalonia are the top-ranked regions for cultural and sea tourism; La Rioja is best positioned for wine and rural tourism, and the Canary Islands perform best for the sea and rural profile. On average, the main efficiency results by region indicate that the Basque country, Catalonia, La Rioja, Madrid and the Canary Islands perform better than other regions.

We also explore efficiency drivers focusing on a set of business factors, macroeconomic variables and environmental variables such as tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay. Multivariate models—Tobit and bootstrapped regressions—indicate that business factors and environmental variables are drivers of firm efficiency. Specifically, efficiency scores are positively and statistically significantly associated with cash flows, legal form, tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay, whereas efficiency scores are negatively and statistically significantly associated with the 2008 financial crisis, size and leverage. In addition, the study provides a robustness analysis using a DEA model with radial DEA model proposed by Banker et al. [

55] in order to confirm prior findings; the results remain similar.

Since the prior efficiency literature and empirical tourism efficiency analysis have primarily focused on hotel firms, there is no evidence reported from other subsectors such as the holiday and short-stay accommodation industry. However, if we compare the results of this study with prior efficiency tourism studies (mainly focusing on hotels firms) we find some similarities and differences. Similarly to Radovanov et al. [

4], Assaf et al. [

17], Lado-Sestayo and Fernández-Castro [

24], Sellers-Rubio and Casado-Díaz [

25], Botti et al. [

29], Yang et al. [

38], we find that the environmental variables (tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay) are strong drivers of firm efficiency. Furthermore, the previous tourism efficiency literature provide evidence that firm size is a key factor or driver of hotel efficiency: Barros [

10], Parte and Alberca [

12], Assaf et al. [

17], Assaf and Agbola [

20]. In this study, in the empirical context of hostels and apartments, we also find that firm size is a key factor linked with firm efficiency.

Following the prior literature, location is a main factor or driver in tourism firm efficiency: Assaf and Tsionas [

8], Barros [

10], Parte and Alberca [

12], Shang et al. [

16], Lado-Sestayo and Fernández-Castro [

24], Chaabouni [

26], Botti et al. [

29], Huang et al. [

37], Yang et al. [

38]. The main results of this study also confirm the above evidence: geographical location is also a key efficiency factor or variable that influences firm efficiency in the holiday and short-stay accommodation industry (hostels and tourist apartments).

6. Conclusions

Since tourism efficiency analysis has mainly focused on hotel firms, this study analyses dynamic efficiency in the holiday and short-stay tourism accommodation industry (e.g., apartments and hostels), on which there is limited evidence to date.

Based on two methodological stages, the study applies several DEA models to investigate the efficiency of tourism firms and the associated variables or drivers. The study uses a non-radial frontier DEA model in order to measure the efficiency and competitiveness of tourism firms. This nonparametric model offers important advantages over classic radial models: it takes into account all inefficiencies (both radial and non-radial) and is invariant to the units of measurement.

A major contribution of this study to the previous efficiency literature is the industry under analysis—the holiday and short-stay tourism accommodation industry—in conjunction with the segmentation associated with the firms’ geographical locations on tourist destinations (non-diversified destinations and diversified destinations; including some tourism dimensions as rural, cultural and wine tourism), as well as the application of several methodologies and sensitivity analyses to confirm the results. This research combines more advanced methods such as the non-radial with radial DEA models to confirm the results. By using several DEA approaches, the study provides further evidence and contributes to a better understanding of efficient firm management as well as confirming efficiency drivers.

The efficiency results confirm the impact of the financial crisis (2008–2011) on tourism firms. The results also indicate that firms geographically located in diversified destinations obtain better efficiency results than those located in non-diversified destinations. Furthermore, considering regional efficiency, the most efficient firms are located in the Basque country, Catalonia, La Rioja, Madrid and the Canary Islands.

Another findings of this study also confirms the influence of some environmental and business variables on firm efficiency: factors such as legal form, cash flow, tourist arrivals, overnight stays and average stay are positive and significantly associated with efficiency score, whereas factors such as the 2008 financial crisis, firm size and leverage are negative and significantly associated with efficiency score.

Business efficiency is closely linked to sustainability: the efficient firms can achieve their production goals with the lowest consumption of resources and responsible production (Goal 12 of SGD). The evidence for the holiday and other short-stay accommodation sector may help entrepreneurs, tourism policymakers and practitioners in their decision-making and development of new strategies seeking the behaviour of the most efficient companies by regions and tourist destination types. The results also confirm that the diversification of the tourist destination based on some tourism dimensions (rural, cultural and wine tourism) is a useful strategy for improving tourist firms’ performance and competitiveness. With respect to efficiency drivers, the evidence indicates that managerial effectiveness with respect to environmental variables, business variables and macroeconomic factors (positively or negatively) can influence tourist firms’ performance.

7. Limitations and Future Developments

In this study, we focus on economic efficiency, generally related to a lower consumption of inputs or productive resources. The efficiency score is estimated using the input variables (capital, labour and materials), which included all the productive resources of each firm. The database used in the paper collects financial and non-financial information for each firm but does not contain specific information related to the sustainable resources and investments of each firm. This is a limitation that can be addressed in future papers. Furthermore, it could be interesting to use additional databases and collect specific information for each firm to examine, for example, eco-efficiency practices such as investments in solar and renewable energy and other aspects. Depending on the available data, it could be interesting to include alternative inputs and outputs to measure efficiency.

Finally, it is worth noting that the empirical analysis in this study assesses efficiency in the holiday and short-stay tourism accommodation industry using several nonparametric frontier estimation approaches, and examines a set of efficiency drivers through multivariate modelling. The results and conclusions of this study could change if other sectors (hotels, restaurants), other countries and regions, and other methodological approaches were considered.

Future studies could extend the results by using an international sample of short-stay accommodation firms. The introduction of more business factors, environmental variables and macroeconomics factors may also reinforce the comparability of this results. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing severe disruptions in the tourism industry; future studies should examine the pandemic effects in all the subsectors from a broad perspective.