Managerial Strategies for Long-Term Care Organization Professionals: COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

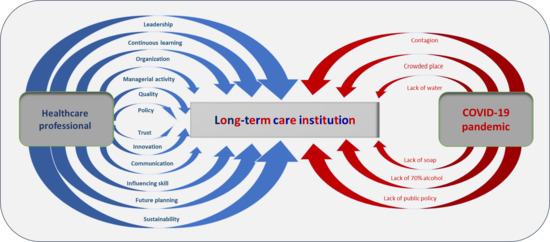

2. The Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Strategies to Prevent the COVID-19 Pandemic in Long-Term Care Organizations

2.2. Competencies for Healthcare Professionals

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Empirical Research

3.2. The Theoretical Research

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rio de Janeiro State Health Secretary. Saúde do Idoso. 2020. Available online: https://www.saude.rj.gov.br/atencao-primaria-a-saude/areas-tecnicas/saude-do-idoso#:~:text=A%20SA%C3%9ADE%20DO%20IDOSO%20NO%20ESTADO%20DO%20RJ&text=Ainda%20de%20acordo%20com%20o,de%201.078.991%20mil%20idosos (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Agência Brasil. Brasileiros com 65 anos ou mais são 10,53% da população, diz FGV. 2020. Available online: https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/saude/noticia/2020-04/brasileiros-com-65-anos-ou-mais-sao-10-53-da-populacao-diz-FGV (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Portal da Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Estudo mostra que população do Rio será mais idosa em 2065. Available online: http://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/guest/exibeconteudo?id=5943906 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Camarano, A.A.; Kanso, S. As instituições de longa permanência para idosos no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Estud. Popul. 2010, 27, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Portal da Cidade de São Paulo. Instituição de Longa Permanência para Idoso (ILPI). Available online: http://www.capital.sp.gov.br/cidadao/familia-e-assistencia-social/centros-de-acolhida/centros-de-acolhida-especial/instituicao-de-longa-permanencia-para-idoso-ilpi (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- ANVISA. Resolução de Diretoria Colegiada—RDC No. 283, de 26 de Setembro de 2005. Available online: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/10181/2718376/RDC_283_2005_COMP.pdf/a38f2055-c23a-4eca-94ed-76fa43acb1df (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- ACASA. O papel das instituições de longa permanência para idosos. 2020. Available online: https://www.grupoacasa.com.br/ilpi/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Creutzberg, M.; Gonçalves, L.H.T.; Sobottka, E.A.; Ojeda, B.S. A instituição de longa permanência para idosos e o sistema de saúde. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vellingiri, B.; Jayaramayya, K.; Iyer, M.; Narayanasam, A.; Govindasamy, V.; Giridharan, B.; Ganesan, S.; Venugopal, A.; Venkatesan, D.; Ganesan, H.; et al. COVID-19: A promising cure for the global panic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Surveillance Case Definitions for Human Infection with Novel Coronavirus (nCoV). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/surveillance-case-definitions-for-human-infection-withnovel-coronavirus-(ncov) (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Surveillance for COVID-19 Caused by Human Infection with COVID-19 Virus. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331506/WHO-2019-nCoV-SurveillanceGuidance-2020.6-eng.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Brazilian Health Ministry. Coronavirus Covid-19. 2020. Available online: https://coronavirus.saude.gov.br/sobre-a-doença (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Beech, N.; Anseel, F. COVID-19 and Its Impact on Management Research and education: Threats, Opportunities and a Manifesto. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Strengthening the Health System Response to COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/443605/Tech-guidance-6-COVID19-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- Giacomin, K.C. Frente Nacional de Fortalecimento às Instituições de Longa Permanência para Idosos. 2020. Available online: https://coronavirus.saude.gov.br/sobre-a-doenca#o-que-e-covid (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Bittar, O.J.; Nogueira, V.; Mendes, J.D.V. Healthcare and teaching hospitals. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2018, 64, 1058–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, K.; Baker, L.; Egan-Lee, E.; Esdaile, M.; Reeves, S. Advancing Faculty Development in Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Zodpey, S. Need and opportunities for health management education in India. Public Health Educ. 2010, 54, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, E.R.B. La educacion medica global en funcion de la salud global. Educ. Med. Super. 2016, 30, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos Junior, C.J.; Misael, J.R.; da Silva, M.R. Educação Médica e Formação na Perspectiva Ampliada e Multidimensional: Considerações acerca de uma Experiência de Ensino-Aprendizagem. Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2019, 43, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, P.F.; Liang, Z.; Leggat, S.; Karimi, L. Validation of a management competency assessment tool for health service managers. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2017, 32, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, G.R.d. Diseño e implementacion de un curriculo por competencias para la formación de médicos. Rev. Perú Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2014, 31, 572–581. [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks, P.; Hobbs, L.; Tippett, V.; Aitken, P. Paramedic Disaster Health Management Competencies: A Scoping Review. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2018, 34, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.G.; Narattharaksa, K.; Siripornpibul, T.; Briggs, D. An assessment of management competencies for primary health care managers in Timor-Leste. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 35, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, S.; Last, J.; Finnegan, H.; O’Connor, K.; Cullen, W. What are the current ‘top five’ perceived educational needs of Irish general practitioners? Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 189, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, J.R.; Pandit, M. Why healthcare leadership had no Coronavirus infection embrace quality improvement. Qual. Improv. 2020, 368, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenzi, A.; Capolongo, S.; Ricciardi, G.; Signorelli, C.; Napier, D.; Rebecchi, A.; Spinato, C. New competences to manage urban health: Health City Manager core curriculum. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E.H.; Taylor, L.A.; Cuellar, C.J. Management Matters: A Leverage Point for Health Systems Strengthening in Global Health. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2015, 4, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Picoli, R.P.; Domingo, A.L.A.; dos Santos, S.C.; de Andrade, A.H.G.; Araujo, C.A.F.; de Mattos Martins Kosloski, R.; da Costa Dias, T.L. Competências Propostas no Currículo de Medicina: Percepção do Egresso. Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2017, 41, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovacic, H.; Rus, A. Leadership Competences in Slovenian Health Care. Zdrav. Var. 2015, 54, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersson, T. The medical leadership challenge in healthcare is an identity challenge. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2015, 28, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, D.H. Ten Core Competencies for Hospital Administrators. Health Care Manag. 2017, 36, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, S.; Lanza, G.; Enna, C.; Zangrandi, A. Managerial competences in public organisations: The healthcare professionals’ Perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harrison, R.; Meyer, L.; Chauhan, A.; Agaliotis, M. What qualities are required for globally relevant health service managers? An exploratory analysis of health systems internationally. Glob. Health 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayeleke, R.O.; North, N.H.; Dunham, A.W.; Katharine, A. Impact of training and professional development on health management and leadership competence A mixed methods systematic review. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2018, 33, 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, T.; Ashill, N.J. The effects of high-performance work practices on job outcomes: Evidence from frontline employees in Russia. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2013, 31, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirey, M.R. Strategic Leadership for Organizational Change. JONA 2015, 45, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.D.C. Leadership in healthcare. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2013, 14, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Riet, M.C.P.; Berghout, M.A.; Samardz, M.B.; van Exel, J.; Hilders, C.G.J.M. What makes an ideal hospital-based medical leader? Three views of healthcare professionals and managers: A case study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller-Hayon, O.; Korn, L.; Magnezi, R. The contribution of the health management studies program to the professional status of graduates. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2015, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Quisenberry, D. Estimating return on leadership development investment. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 27, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghout, M.A.; Fabbricotti, I.N.; Buljac-Samardzic, M.; Hilders, C.G.J.M. Medical leaders or masters? A systematic review of medical leadership in hospital settings. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0120317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karimi, L.; Dadich, A.; Fulop, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Rada, J.; Hayes, K.J.; Kippist, L.; Eljiz, K.; Smyth, A.; Fitzgerald, J.A. Empirical exploration of brilliance in health care: Perceptions of health professionals. Aust. Health Rev. 2017, 41, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavarda, A.; Dau, G.; Scavarda, L.F.; Azevedo, B.D.; Korzenowski, A.L. Social and ecological approaches in urban interfaces: A sharing economy management framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 713, 134407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, N.G.; Decker, F.H. Top management leadership style and quality of care in nursing homes. Gerontologist 2011, 5, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjøs, B.Ø.; Botten, G.; Gjevjon, E.R.; Romøren, T.I. Quality work in long-term care: The role of first-line leaders. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2010, 22, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M.R.; Roos, M.; Kantanen, K.; Suominen, T. International Nursing: Nurse Managers’ Leadership and Management Competencies Assessed by Nursing Personnel in a Finnish Hospital. Nurs. Admin. Q. 2018, 42, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingvoll, W.A.; Saeterstrand, T.; McClusky, M. The challenges of primary health care nurse leaders in the wake of New Health Care Reform in Norway. BMC Nurs. 2016, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Macphee, M.; Suryaprakash, N. First-line nurse leaders health-care change management initiatives. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charette, M.; Goudreau, J.; Bourbonnais, A. How do new graduated nurses from a competency-based program demonstrate their competencies? A focused ethnography of acute care settings. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 79, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.K.; Dennehy, C.; Fitzsimmons, A.; Hyde, S.; Lee, K.; Rivera, J.; Shunk, R.; Wamsley, M. Teaching interprofessional collaborative care skills using a blended learning approach. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussami, M.; Hamad, S.; Darawad, M.; Maharmeh, M. The effects of leadership competencies and quality of work on the perceived readiness for organizational change among nurse managers. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2017, 3, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyo, P.; Swartwout, E.; Drenkard, K. Nurse Manager Competencies Supporting Patient Engagement. JONA 2016, 46, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.J.; Pedersen, C.G.; Martin, H.M.; Lomborg, K. Implementation of patient involvement methods in the clinical setting: A qualitative study exploring the health professional perspective. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2019, 26, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantanen, K.; Kaunonen, M.; Helminen, M.; Suominen, T. Leadership and management competencies of head nurses and directors of nursing in Finnish social and health care. J. Res. Nurs. 2017, 22, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Damanpour, F.; Schneider, M. Phases of the Adoption of Innovation in Organizations: Effects of Environment, Organization and Top Managers. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, R.; Scott, S.D.; Rotter, T.; Hartfield, D. The potential for nurses to contribute to and lead improvement science in health care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giacomelli, G.; Ferre, F.; Furlan, M.; Nuti, S. Involving hybrid professionals in top management decision-making: How managerial training can make the difference. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2019, 32, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Burgess, N.; Hayton, J.C. HR practices and knowledge brokering by hybrid middle managers in hospital settings: The influence of professional hierarchy. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K.; Tuomikoski, A.M.; Sjögren, T.; Koivula, M.; Koskimäki, M.; Lähteenmäki, M.L.; Mäki-Hakola, H.; Wallin, O.; Sormunen, M.; Saaranen, T.; et al. Development and testing of an instrument (HeSoEduCo) for health and social care educators’ competence in professional education. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 84, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannocci, A.; di Bella, O.; Barbato, D.; Castellani, F.; La Torre, G.; de Giusti, M.; del Cimmuto, A. Assessing knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare personnel regarding biomedical waste management: A systematic review of available tools. Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, B.D.; Scavarda, L.F.; Caiado, R.G.G. Urban solid waste management in developing countries from the sustainable supply chain management perspective: A case study of Brazil’s largest slum. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, A.L.C.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Scavarda, A.J. Sustainable urban infrastructure: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magon, R.B.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Ferrer, A.L.C.; Scavarda, L.F. Sustainability and performance in operations management research. J. Clean. Prod 2018, 190, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavarda, A.; Daú, G.L.; Scavarda, L.F.; Korzenowski, A.L. A proposed healthcare supply chain management framework in the emerging economies with the sustainable lenses: The theory, the practice, and the policy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojekalu, S.O.; Ojo, O.; Oladokun, T.T.; Olabisi, S.A. Factors influencing service quality- An empirical evidence from property managers of shopping complexes in Ibadan, Nigeria. Prop. Manag. 2018, 37, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M. Qualifications and Competencies for Population Health Management Positions: A Content Analysis of Job Postings. Popul. Health Manag. 2017, 20, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.C.; Reis, A.C.; Oliveira, R.P.; Maruyama, U.G.R.; Martinez, P. Lean Manufacturing in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of Literature. Rev. Produção Desenvolv. 2018, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, G.; Scavarda, A.; Scavarda, L.F.; Portugal, V.J.T. The Healthcare Sustainable Supply Chain 4.0: The Circular Economy Transition Conceptual Framework with the Corporate Social Responsibility Mirror. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scavarda, A.; Dau, G.; Scavarda, L.F.; Caiado, R.G.G. An Analysis of the Corporate Social Responsibility and the Industry 4.0 with Focus on the Youth Generation: A Sustainable Human Resource Management Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaidya, R.W.; Prasad, K.D.V.; Mangipudi, M.R. Mental and Emotional Competencies of Leader’s Dealing with Disruptive Business Environment—A Conceptual Review. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, D.A.; Smerek, R.E.; Thomas-Hunt, M.C.; James, E.H. The real-time power of Twitter: Crisis management and leadership in an age of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brian, Y.A.; Tang, S.Y. Lessons From COVID-19 Responses in East Asia: Institutional Infrastructure and Enduring Policy Instruments. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.; Briggs, R.; Holmerová, I.; Samuelsson, O.; Gordon, A.L.; Martin, F.C. COVID-19 highlights the need for universal adoption of standards of medical care for physicians in nursing homes in Europe. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.J.; Self, M.M.; Davis, C., III; Conway, F.; Crepeau-Hobson, F. University of Health Service Psychology Education and Training in the Time of COVID-19: Challenges and Opportunities. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, O.; Zimmermann, J.; Ares, G. Surgical Residents in the Battle Against COVID-19. J. Surg. Educ. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirani, K.M.; Abadi, M.; Alizadeh, A.; Barhate, B.; Garza, R.C.; Gunasekara, N.; Ibrahim, G.; Majzun, Z. Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: A response to Covid-19 pandemic. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, R.M.; Schärrer, L. Outpacing the pandemic? A factorial survey on decision speed of COVID-19 task forces. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2020, 7, 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mike, E.V.; Laroche, D. Preserving Vision in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Focus on Health Equity. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 2073–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxton, C.E.; Nace, D.A.; Nazir, A. Solving the COVID-19 Crisis in Post-Acute and Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Y. Medical leadership: An important and required competency for medical students. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2018, 30, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, D. Healthcare educational leadership in the twenty-first century. Med Teach. 2019, 41, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Universidade Aberta da Terceira Idade (UNATI). Relação das Instituições de Longa Permanência para Idosos do Município do Rio de Janeiro. 2015. Available online: http://www.unatiuerj.com.br/relacao.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Brazilian Health Ministry. Covid-19 no Brasil. 2020. Available online: https://susanalitico.saude.gov.br/extensions/covid-19_html/covid-19_html.html (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Agência Brasil. Estado do Rio passa de 4 mil mortes por coronavírus. 2020. Available online: https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/saude/noticia/2020-05/estado-do-rio-passa-de-4-mil-mortes-por-coronavirus (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Brazilian Health Ministry. Painel Coronavirus 2020c. Available online: https://covid.saude.gov.br (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Barbosa, F.S.; Scavarda, A.; Sellitto, M.A.; Marques, D.I.L. Sustainability in the winemaking industry: An analysis of Southern Brazilian companies based on a literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 192, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Competency | Author |

|---|---|

| Attending clinical forums | [32] |

| Balancing management theory and practice | [34] |

| Collaborative managers and compassionate leaders | [34] |

| Communication | [24,33,39,51,55] |

| Community and customer assessment and engagement | [28] |

| Continuous learning | [25,27,28,34] |

| Cooperating for public benefit | [32] |

| Demonstrating personal qualities | [28] |

| Disclosing and genuinely empathizing about medical errors and futile care | [32] |

| Donating | [32] |

| Engaging with clinical partners | [32] |

| Engaging in the culture and environment | [40] |

| Experiencing all shifts | [32] |

| Experiencing hospital services | [32] |

| Financial management | [24] |

| Governance and leadership | [28] |

| Human resource management | [28] |

| Improving services | [67] |

| Influencing skill | [55,56] |

| Innovation | [55,56,66,81,82] |

| Leadership | [21,24,26,30,31,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,49,50,51,52,66,81,82] |

| Managing and making change | [34] |

| Managing services | [28,34] |

| Organization | [31,35,36,48] |

| Performance management and accountability | [28] |

| Political analysis and dialogue | [28] |

| Political and legal issues | [55,56] |

| Quality | [45,46,47,55,68] |

| Remaining actively on call | [32] |

| Research | [55,56] |

| Setting direction | [55] |

| Sending a condolence card | [32] |

| Topic strategic thinking and problem solving | [24,28] |

| Visiting physicians and nurses where they work | [32] |

| Waste disposal (sustainability) | [62,63,64,65] |

| Working with others | [55] |

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | Standard Deviation | Sum | Coefficient of Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The capacity before the Coronavirus pandemic | 11 | 80 | 31.00 | 37.10 | 20.07 | 742 | 0.54 |

| The capacity after the appearance of the Coronavirus pandemic | 11 | 80 | 30.50 | 36.15 | 19.63 | 723 | 0.54 |

| The number of residents before the Coronavirus pandemic | 11 | 69 | 27.50 | 31.70 | 18 | 634 | 0.56 |

| The number of residents after the appearance of the Coronavirus pandemic | 11 | 69 | 27.50 | 32.15 | 18 | 643 | 0.56 |

| The occupancy rate before the Coronavirus pandemic | 56.5% | 100.0% | 88.11% | 85.43% | 13.01% | - | 0.15 |

| The occupancy rate after the appearance of the Coronavirus pandemic | 63.2% | 108.0% | 93.30% | 88.22% | 15.06% | - | 0.17 |

| Level | Competency | Professional |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital (professional practice) | Leadership | All professionals |

| Communication | All professionals | |

| Innovation | All professionals | |

| Influencing skill | All professionals | |

| Research | Physicians and nurses | |

| Organization | All professionals | |

| Political and legal issues | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Financial management | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Quality | All professionals | |

| Managing and bringing about change | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Performance management and accountability | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Experiencing all shifts | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Political analysis and dialogue | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Attending clinical forums | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Engaging with clinical partners | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Experiencing hospital services | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Disclosing and genuinely empathizing about medical errors and futile care | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Cooperating for public benefit | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Remaining actively on call | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Balancing management theory and practice | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Sending a condolence card | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Collaborative managers and compassionate leaders | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Continuous learning | All professionals | |

| Topic strategic thinking and problem solving | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Human resource management | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Donating | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Governance and leadership | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Visiting physicians and nurses where they work | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Community and customer assessment and engagement | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Engaging in the culture and environment | Managers (healthcare leaders) | |

| Waste disposal (sustainability) | All professionals | |

| Working with others | Nurses (healthcare leaders) | |

| Demonstrating personal qualities | Nurses (healthcare leaders) | |

| Setting direction | Nurses (healthcare leaders) | |

| Managing services | Nurses (healthcare leaders) | |

| Improving services | Nurses (healthcare leaders) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dias, A.; Scavarda, A.; Reis, A.; Silveira, H.; Ebecken, N.F.F. Managerial Strategies for Long-Term Care Organization Professionals: COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229682

Dias A, Scavarda A, Reis A, Silveira H, Ebecken NFF. Managerial Strategies for Long-Term Care Organization Professionals: COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229682

Chicago/Turabian StyleDias, Ana, Annibal Scavarda, Augusto Reis, Haydee Silveira, and Nelson Francisco Favilla Ebecken. 2020. "Managerial Strategies for Long-Term Care Organization Professionals: COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229682

APA StyleDias, A., Scavarda, A., Reis, A., Silveira, H., & Ebecken, N. F. F. (2020). Managerial Strategies for Long-Term Care Organization Professionals: COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts. Sustainability, 12(22), 9682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229682