Sustaining Rainforest Plants, People and Global Health: A Model for Learning from Traditions in Holistic Health Promotion and Community Based Conservation as Implemented by Q’eqchi’ Maya Healers, Maya Mountains, Belize

Abstract

:1. Introduction

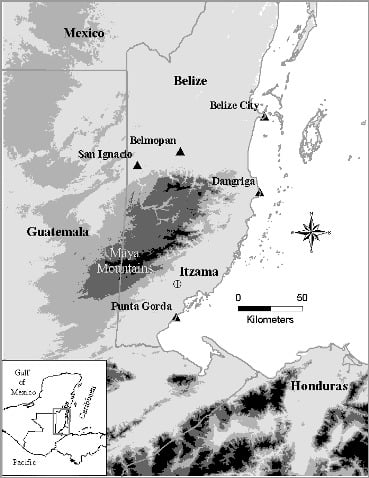

1.1. Maya Mountains Region

1.2. Itzama

1.3. Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Informed Consent and Ethics

2.2. Q’eqchi’ Maya Healers

2.3. Study Sites and Collections

3. Results

| Family | Scientific name | Q'eqchi' name | In Garden |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Aphelandra scabra (Vahl.) Sm. | Saxjolom chacmut #2 (Sita pim) | Y |

| Blechum pyramidatum (Lam.) Urb. | None | N | |

| Justicia aff.fimbriata (Nees) V.A.W. Graham | Saxjolom chacmut #1 | N | |

| Justicia pectoralis Jacq. | Santa Maria kejen | Y | |

| Mendoncia lindavii Rusby | None | N | |

| Adiantaceae | Adiantum petiolatum Desv. | None | Y |

| Adiantum pulverulentum L. | Sis' bi pim | N | |

| Adiantum wilsonii Hook. | Ruj' i' rak' aj tza | N | |

| Annonaceae | Annona aff. glabra L. | Ho' lo' bob | N |

| Apiaceae | Eryngium foetidum L. | Samat | N |

| Apocynaceae | Thevetia ahouai (L.) A.DC. | Chi' chi tyak | N |

| Araceae | Anthurium willdenowii Kunth. | Xchich ma'us | Y |

| Araliaceae | Dendropanax arboreus (L.) Decne.& Planch. | Cojl | Y |

| Aspleniaceae | Bolbitis pergamentacea (Maxon) Ching. | None | N |

| Elaphoglossum herminieri (Bory ex Fée) T. Moore | Rubelsa' i' xul #2 | N | |

| Elaphoglossum peltatum (Sw.) Urb. | Culantro pim | N | |

| Asteraceae | Baccharis trinervis Pers. | None | N |

| Chromolaena odorata (Lam.) R.M. King & H. Rob. | None | Y | |

| Mikania micrantha H.B.K. | Cha' ko' nob #1 | N | |

| Neurolaena lobata (L.) R. Br.ex Cass. | Q'an mank | Y | |

| Piptocarpha poeppigiana (DC.) Baker | Chu' nac kejen #2 | N | |

| Pluchea odorata (L.) Cass. | None | N | |

| Asteraceae | Vernonia stellaris La Llave & Lex. | Hob' lob' te | N |

| Begoniaceae | Begonia glabra Aubl. | Kak' i' pim #1 (Pa'u'lul #3) | N |

| Begonia heracleifolia Schltdl.& Cham.. | Xac' peck (Pa'u'lul #1) | N | |

| Begonia nelumbiifolia Schltdl.& Cham. | Pa' u' lul #2 | Y | |

| Burseraceae | Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. | Kakajl | N |

| Cactaceae | Epiphyllum phyllanthus (L.) Haw. var strictum (Lem.) Kimnach Wilmattea minutiflora (Britton & Rose) Britton & Rose. | Chic' ba' bac #2Chic’ ba’ bac #1 | YN |

| Campanulaceae | Hippobroma longiflora (L.) G. Don. | None | Y |

| Clusiaceae | Vismia baccifera (L.) Triana & Planch. | Q’an para’ quay | N |

| Combretaceae | Combretum fruticosum (Loefl.) Stuntz. | Kan shan cahan | N |

| Commelinaceae | Dichorisandra hexandra (Aubl.) Standl. | Tzima’aj pim | N |

| Tripogandra grandiflora (Donn.Sm.) Woodson | Tzima'aj kejen #2 | N | |

| Convolvulaceae | Merremia dissecta (Jacq.) Hallier f. | Is caham | Y |

| Merremia tuberosa (L.) Rendle | None | N | |

| Costaceae | Costus laevis Ruiz & Pav. | Chu’ un | Y |

| Cucurbitaceae | Gurania makoyana (Lem.) Cogn. | Cu’ um pim | N |

| Melothria pendula L. | Sandia cho' | N | |

| Momordica charantia L. | Ya’ mor | N | |

| Davalliaceae | Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott. | Xqu’q moco’ ch | N |

| Dilleniaceae | Davilla kunthii A. St.-Hil. | Kak’ I’ caham | N |

| Euphorbiaceae | Chamaesyce hyssopifolia (L.) Small. | None | N |

| Croton schiedeanus Schltdl. | Copal chi | N | |

| Euphorbia lancifolia Schltdl. | None | N | |

| Fabaceae-Caesalpinioideae | Senna alata (L.) Roxb. | Bajero pim | N |

| Senna hayesiana (Britton & Rose) H.S. Irwin & Barneby | Carabans’ I’ che | N | |

| Fabaceae-Mimosoideae | Desmodium adscendens (Sw.) DC. | Ch'in pim | Y |

| Fabaceae-Papilionoideae | Acosmium panamense (Benth.) Yakovlev | Ka che | Y |

| Machaerium cirrhiferum Pittier | Lokoch kix | Y | |

| Tephrosia multifolia Rose | Chalam | N | |

| Gesneriaceae | Besleria laxiflora Benth. | Kehal pim | Y |

| Columnea sulfurea Donn. Sm. | Kak’ I’ pim #2 | Y | |

| Haemodoraceae | Xiphidium caeruleum Aubl. | Xcual’ I’ cu’ uch | Y |

| Lamiaceae | Hyptis capitata Jacq. | Se’ ruj’ kaway | N |

| Hyptis verticillata Jacq. | Chu pim | N | |

| Loganiaceae | Strychnos panamensis Seem. | Curux kix | N |

| Malvaceae | Sida acuta Burm. f. | Mes’ beel | N |

| Marattiaceae | Danaea aff. nodosa (L.) Sm. | None | N |

| Marcgraviaceae | Souroubea gilgii V.A. Richt. | Hu’ bub | N |

| Melastomataceae | Adelobotrys adscendens (Sw.) Triana | Chu’ nac kejen #1 | N |

| Arthrostemma ciliatum Pav. ex D. Don. | Roq za’ ak | Y | |

| Blakea cuneata Standl. | Oxlaju chajom | Y | |

| Clidemia capitellata (Bonpl.) D. Don. var dependens (D. Don.) J.F. Macbr. | Ix pim #2 | Y | |

| Miconia oinochrophylla Donn. Sm. | None | Y | |

| Menispermaceae | Abuta panamensis (Standl.) Krukoff & BarnebyCissampelos pareira L. | NoneChup’ I’ al #3 | YY |

| Cissampelos tropaeolifolia DC. | Chup’ I’ al #1 | N | |

| Monimiaceae | Mollinedia guatemalensis Perkins | Sak’ I’ kejen #1 | Y |

| Moraceae | Dorstenia contrajerva L. | Chup’ I’ al #2 | Y |

| Ficus insipida Willd. | Hu’u | Y | |

| Myrtaceae | Calyptranthes chytraculia (L.) Sw. | Noone | N |

| Eugenia rhombea (O. Berg.) Krug & Urb. | Lamush pim | N | |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora oerstedii Mast. var choconiana (S. Watson) | Tu’ key #1 | N |

| Passiflora guatemalensis S. Watson | Tu’ key #2 | N | |

| Piperaceae | Peperômia hispidula (Sw.) A. Dietr. | Xcua’ I’ xul | Y |

| Peperomia matlalucaensis C. DC. | None | N | |

| Piper amalago L. | Tzi’ ritok | Y | |

| Piper hispidum Sw. | Kan pom | N | |

| Piper peltatum L. | Tyut’ it | Y | |

| Piper schiedeanum Steud. | None | Y | |

| Piper tuerckeimii C.DC. ex Donn. Sm. | Cux’ sawe | N | |

| Piper yucatanense C. DC. | Tzu’ lub pim | N | |

| Polygalaceae | Securidaca diversifolia (L.) S.F. Blake | Seru qantyaj or Chup qantyaj | N |

| Polypodiaceae | Campyloneurum brevifolium (Lodd.ex Link) Link | Rix’ I’ xul | N |

| Rhamnaceae | Gouania lupuloides (L.) Urb. | Cha’ jom caham #1 | N |

| Rubiaceae | Chiococca alba (L.) Hitchc. | Par’ I’ pim | N |

| Gonzalagunia panamensis (Cav.) K.Schum. | Tzu’ ul che | Y | |

| Morinda citrifolia L. | Q’an I’ che | Y | |

| Psychotria glomerulata (Donn.Sm.) Steyerm. | None | Y | |

| Sabicea villosa Willd. ex Roem.& Schult. | Tu’ zub caham #1 | N | |

| Spermacoce tenuior L. | None | N | |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum petenense Lundell | None | N |

| Schizaeaceae | Lygodium heterodoxum Kunze | Ruxb’ I’ kaak #1 | N |

| Lygodium venustum Sw. | Ruxb’ I’ kaak #2 | Y | |

| Selaginellaceae | Selaginella umbrosa Lem. ex Hieron. | None | Y |

| Selaginella aff. stellata Spring | None | N | |

| Tectariaceae | Dictyoxiphium panamense Hook. | Usi’ xu’ ul kejen | Y |

| Tiliaceae | Triumfetta semitriloba Jacq. | Cuo’ yo | N |

| Verbenaceae | Aegiphila monstrosa Moldenke | Roq xa’an | N |

| Lantana trifolia L. | Tu’ lush | Y | |

| Phyla dulcis (Trevir.) Moldenke | None | N | |

| Stachytarpheta jamaicensis (L.) Vahl. | Tye’ aj’ pak | Y | |

| Vitaceae | Cissus microcarpa Vahl. | Roq’ hab | N |

| Vitis tiliifolia Humb. & Bonpl.ex Roem.& Schult. | Tu’ zub caham #2 | Y | |

| Zamiaceae | Zamia picta Dyer. | Cykad | N |

| Family | Scientific name | Q’eqchi name |

|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Aphelandra aurantiaca (Scheidw.) Lindl. | Sa’x jolom Chacmut |

| Acanthaceae | Justicia aurea Schltdl. | Chak Mut K’ak |

| Acanthaceae | Ruellia matagalpae Lindau | Kuuw Kub K’ejen |

| Adiantaceae | Pteris pungens Willd. | Rok Chicuan’ |

| Amaranthaceae | Iresine diffusa Willd. | Birritak |

| Araceae | Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G. Don | Marak’a |

| Araliaceae | Oreopanax obtusifolius L. O. Williams | Bak Pim |

| Aristolochiaceae | Aristolochia tonduzii O. C. Schmidt | San Sar K’egem |

| Aspleniaceae | Asplenium serratum L. | Rix I Xul |

| Asteraceae | Mikania guaco Humb. & Bonpl. | Ramn Kantiaj |

| Asteraceae | Porophyllum punctatum (Mill.) S. F. Blake | Só Sol Pim |

| Bignoniaceae | Tynanthus guatemalensis Donn. Sm. | Chi Vi Vayal |

| Boraginaceae | Cordia spinescens L. | Ekex eb |

| Buddlejaceae | Buddleja americana L. | Job lo Te |

| Burseraceae | Protium glabrum (Rose) Pittier | Pon Te |

| Caesalpinaceae | Senna hayesiana (Britton & Rose) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | Keenk Maus |

| Caesalpinaceae | Dialium guianense (Aubl.) Sandwith | Holobob |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia amazonica (J. F. Gmel.) Excell | Kaa Chan |

| Commelinaceae | Tradescantia zebrina hort. ex Bosse | Simak |

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | None |

| Dracaenaceae | Dracaena americana Donn. Sm. | Tut |

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton xalapensis H. B. K. | Nok Te |

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha arvensis Poepp. | Káak Ukuub |

| Lamiaceae | Scoparia dulcis L. | Chúu Pim / Ix Ye Kavay |

| Loganiaceae | Strychnos brachistantha Standl. | Curux K'ix |

| Loganiaceae | Spigelia humboldtiana Cham. & Schltdl. | Se Ru Ixúl |

| Lomariopsidaceae | Elaphoglossum herminieri (Bory ex Fée) T. Moore | X'na Tulux |

| Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth | Chii |

| Malvaceae | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav. Var. Mexicanus Schltdl. | Ix |

| Malvaceae | Heliocarpus mexicanus (turcz.) Sprague | Saky baych |

| Malvaceae | Pavonia paniculata Cav. | Mul Tzi |

| Margraviaceae | Souroubea gilgii V. A. Richt. | Hub’ ub’ |

| Melastomataceae | Arthrostemma ciliatum Pav. Ex D. Don | |

| Melastomataceae | Clidemia crenulata Gleason | Tzó Pim |

| Meliaceae | Guarea grandifolia DC. | Bol bo |

| Mimosaceae | Mimosa pudica L. | Wara Kix |

| Monimiaceae | Siparuna thecaphora (Poepp. & Endl.) A. DC. | Chú che |

| Myrtaceae | Pimenta guatemalensis (Lundell) Lundell | Pens |

| Onagraceae | Hauya elegans DC. Subsp. Lucida (Donn. Sm. & Rose) P. H. Raven & Breedlove | Conop |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora guatemalensis S. Watson | A’tzam Pim |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora sexflora Juss. | Pepem pim |

| Phytolaccaceae | Rivina humilis L. | None |

| Phytolaccaceae Piperaceae | Petiveria alliacea L. Piper aff. aequale Vahl | Paara PimPuchush Kamil |

| Piperaceae | Peperomia tetraphylla (G. Forst.) Hook. & Arm. | Puchsh Retzul |

| Piperaceae | Piper arboreum Aubl. | Saki Puchuu |

| Piperaceae | Piper marginatum Jacq. | Kan Puchuu |

| Piperaceae | Piper umbellatum L. | Obel |

| Piperaceae | Peperomia obtusifolia (L.) A. Dietr. | Ix Wa Ajauchán |

| Rhizophoraceae | Cassipourea guianensis Aubl. | Zeruj Jauyán |

| Rosaceae | Photinia microcarpa Standl. | |

| Rubiaceae | Posoqueria latifolia (Rudge) | Jom Che |

| Rubiaceae | Spermacoce assurgens Ruiz & Pav. | Ix Warriba I Chookl |

| Rubiaceae | Hamelia rovirosae Wernham | Chaaj Max / Jolom Ipos |

| Rubiaceae | Psychotria poeppigiana Müll. Arg. | X Jolom Tzó Chilan |

| Solanaceae | Cestrum racemosum Ruiz & Pav. | Akap Kelém |

| Solanaceae | Solanum megalophyllum Dunal | Ic Pim |

| Solanaceae | Solanum rudepanum Dunal | Pajla |

| Tiliaceae | Trichospermum grewiifolium (A. Rich) Kosterm | |

| Verbenaceae | Stachytarpheta frantzii Pol. | Tye Aj Pak |

| Verbenaceae | Cornutia grandifolia (Schltdl. & Cham.) Schauer | Rok Xan |

| Vittariaceae | Ananthacorus angustifolius (Sw.) Underw. & Maxon | Rujrak Xul |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Biodiversity & Environmental Resource Data System (BERDS); World Wide Web Electronic Publication: Belmopan, Belize, 2008. Available online: http://www.biodiversity.bzv (accessed on 1 December 2008).

- Hartshorn, G.; Nicolait, L; Hartshorne, L.; Bevier, G.; Brightman, R.; Cal, J.; Cawich, A.; Davidson, W.; DuBois, R.; Dyer, C.; Gibson, J.; Hawley, W.; Leonard, J.; Nicolait, R.; Weyer, D.; White, H.; Wright, C. Belize, Country Environmental Profile; Trejos, H., San, J., Costa, R., Eds.; Robert Nicolait and Associates: Belize City, Belize, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Balick, M.; Nee, M.; Atha, D. Checklist of Vascular Plants of Belize, with Common Names and Uses; New York Botanical Garden Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek, T.; Cal, M.; Cal, V.; Fini, N.; Minty, C.; Dunham, P.; Arnason, J. Rapid ethnobotanical survey of the Maya Mountains range in Southern Belize: A pilot study. Trees Life J. 2006, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek, T.; Abramiuk, M.; Fini, N.; Otarola-Rojas, M.; Collins, S.; Cal, V.; Sanchez, P.; Poveda, L.; Arnason, J. Q’eqchi’ Maya healers traditional knowledge in prioritizing conservation of medicinal plants: culturally relative conservation in sustaining traditional holistic health promotion. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek, T.; Abramiuk, M.; Garagic, D.; Fini, N.; Meerman, J.; Cal, V. Sustaining plants and people: Traditional Q’eqchi’ Maya botanical knowledge and interactive spatial modeling in prioritizing conservation of medicinal plants for culturally relative holistic health promotion. Ecohealth 2009, 6, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ironmonger, S.; Leisnerm, R.; Sayre, R. Plant records from the natural forest communities in the Bladen Nature Reserve, Maya Mountains, Belize. Caribb. J. Sci. 1995, 3, 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stepp, J.; Castaneda, H.; Cervone, S. Mountains and biocultural diversity. Mt. Res. Dev. 2005, 25, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Treyvaud-Amiguet, V.; Arnason, J.; Maquin, P.; Cal, V.; Sanchez-Vindaz, P.; Poveda, L. A consensus ethnobotany of the Q’eqchi’ Maya of southern Belize. Econ. Bot. 2005, 59, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- World Wildlife Fund. Living Planet Report 2004; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2004.

- Hanski, I. Landscape fragmentation, biodiversity loss and the societal response. EMBO Rep. 2005, 6, 388–392. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization. Global Forest Resources Assessment, 2000. Available online: ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/003/Y1997E/FRA%202000%20Main%20report.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2005).

- Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Arnason, J.; Cal, V.; Assinewe, V.; Poveda, L.; Waldram, J.; Cameron, S.; Pesek, T.; Cal, M.; Jones, N. Visioning Our Traditional Health Care: Workshop on Q’eqchi’ Healers Center, Botanical Garden and Medicinal Plant Biodiversity Project in Southern Belize; Final Report; Submitted to International Development Research Center (IDRC): Ottawa, Canada, 1 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek, T.; Helton, L.; Nair, M. Healing across cultures: Learning from traditions. Ecohealth 2006, 3, 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek, T.; Cal, V.; Fini, N.; Cal, M.; Rojas, M.; Sanchez, P.; Poveda, L.; Collins, S.; Knight, K.; Arnason, J. Itzama: Revival of traditional healing by the Q’eqchi’ Maya of Southern Belize. HerbalGram 2007, 76, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cal, V.; Arnason, J.; Walshe-Rouusel, B.; Audet, P.; Ferrier, J.; Knight, K.; Pesek, T. The Itzama Project: Sustainable Indigenous Development Based on the Ethnobotanical Garden and Traditional Medicine Concept; Final Report Submitted to International Development Research Center (IDRC): Ottawa, Canada, 31 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arvigo, R.; Balick, M. Rainforest Remedies; Lotus Press: Twin Lakes, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Arnason, J.T.; Uck, F.; Hebda, R.; Lambert, J. Maya medicinal plants of San Jose Succotz, Belize. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1980, 2, 345–364. [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth, N.; Akerele, O.; Bingel, A.; Soejarto, D.; Guo, Z. Medicinal plants in therapy. Bull. World Health Organ. 1985, 63, 965–981. [Google Scholar]

- Bourbonnais-Spear, N.; Poissant, J.; Cal, V.; Arnason, J. Culturally important plants from southern Belize: Domestication by Q’eqchi’ Maya healers and conservation. Ambio 2005, 35, 138–140. [Google Scholar]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas, M.O.; Collins, S.; Cal, V.; Caal, F.; Knight, K.; Arnason, J.; Poveda, L.; Sanchez-Vindas, P.; Pesek, T. Sustaining Rainforest Plants, People and Global Health: A Model for Learning from Traditions in Holistic Health Promotion and Community Based Conservation as Implemented by Q’eqchi’ Maya Healers, Maya Mountains, Belize. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3383-3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113383

Rojas MO, Collins S, Cal V, Caal F, Knight K, Arnason J, Poveda L, Sanchez-Vindas P, Pesek T. Sustaining Rainforest Plants, People and Global Health: A Model for Learning from Traditions in Holistic Health Promotion and Community Based Conservation as Implemented by Q’eqchi’ Maya Healers, Maya Mountains, Belize. Sustainability. 2010; 2(11):3383-3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113383

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas, Marco Otarola, Sean Collins, Victor Cal, Francisco Caal, Kevin Knight, John Arnason, Luis Poveda, Pablo Sanchez-Vindas, and Todd Pesek. 2010. "Sustaining Rainforest Plants, People and Global Health: A Model for Learning from Traditions in Holistic Health Promotion and Community Based Conservation as Implemented by Q’eqchi’ Maya Healers, Maya Mountains, Belize" Sustainability 2, no. 11: 3383-3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113383

APA StyleRojas, M. O., Collins, S., Cal, V., Caal, F., Knight, K., Arnason, J., Poveda, L., Sanchez-Vindas, P., & Pesek, T. (2010). Sustaining Rainforest Plants, People and Global Health: A Model for Learning from Traditions in Holistic Health Promotion and Community Based Conservation as Implemented by Q’eqchi’ Maya Healers, Maya Mountains, Belize. Sustainability, 2(11), 3383-3398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113383