3.2. Community Capitals and the Arts

We find that arts-based development relates to each of the seven community capitals. Each capital (or asset type) shapes the circumstances within which arts projects are developed and operate. These characteristics make Calumet both similar to and distinct from other shrunken cities and so have important implications for the generalizability of the findings presented here. At the same time, the various art initiatives contribute to each of the community capitals, sometimes in complex ways. This section both summarizes community characteristics in Calumet and describes how arts-based development is impacting the broader community following the Community Capitals Framework.

Table 1 (on the next page) provides a general overview of the community capitals in Calumet compared to the state of Michigan and the United States. There are no clearly established criteria or specific measures for any of the community capitals. The measures included here were chosen based on data availability and aim to capture a reasonable representation of the various dimensions of each capital. We refer back to the data reported in this table throughout when discussing each of the community capitals in more detail below.

3.2.1. Natural Capital

Historically, copper has defined Calumet and the surrounding area, providing the raw material for the community’s initial boom and an environmental and cultural legacy that continues to shape and define the region. The broader Calumet area is the site of the most extensive known deposits of native copper (relatively pure copper known as “float copper”) that requires little to no processing. Mining of the copper began prehistorically with aboriginal mining to produce jewelry and tools which were traded [

39]. Large scale commercial mining operations began in the mid-nineteenth century and continued until 1968 [

35]. Altogether, Keweenaw copper was mined for thousands of years beginning about 8000 years ago [

39].

The lingering importance of copper is indicated by the extensive use of the word copper in names for festivals and descriptions of the area (

i.e., “CopperDog 150” dogsled race and “Copper Country” or “Copper Island” as a name for the region). The legacy of copper mining also persists in the miles of underground mining tunnels (now flooded), the thirty-seven mine shafts (now capped), slag piles of poor-rock that tower over the landscape, and a Superfund site in a neighboring community where copper mined in Calumet was processed. There is no acid-mine drainage in this area (the rock did not contain sulfides), so compared to other former mining regions, there is relatively little damage to water quality. However, the Torch Lake Superfund site (where the ore was processed) shows evidence of toxic PCBs, mercury, arsenic, and copper in the water and associated fish toxicity [

42].

At the same time, Calumet is rich in other natural resources (

i.e., timber, fresh water) and outdoor recreation opportunities (see

Table 1). The land is heavily forested and access to Lake Superior and its miles of public beaches is about five miles away. The township maintains a public park at the nearest access point that offers sandy beaches, playground equipment, gathering and picnic space, shelters, and basketball courts. The community is centrally located on the Keweenaw Peninsula with easy access to hundreds of miles worth of non-motorized summer and winter recreational trails for hiking, mountain biking, kayaking, snowshoeing, cross country skiing and snow biking. There are seven extensive public non-motorized trail systems within 50 miles of Calumet, each of which includes dozens of miles of maintained trail; and dozens of smaller trails less than ten miles in length.

Within Calumet township, there are at least 53 miles of publically accessible maintained trails, or about 8.2 miles worth for every 1000 residents. Most of these miles are in the Swedetown Recreational Area which includes 30 km (18 miles) of groomed cross-country ski trails plus 10 km (6 miles) of designated snowshoe trails for winter recreation. It also includes 25 miles of singletrack mountain bike trails, plus an additional 20 miles of two-track trails for hiking, biking, and running in the summer months. Snowmobile/ORV trails are also plentiful.

The region is internationally known for its cross-country ski trails and good conditions and regularly hosts national cross country ski competitions. It is also internationally recognized as a mountain biking destination, with the bike trails at Copper Harbor (a half-hour drive from Calumet) one of eighteen communities around the world designated as an International Mountain Biking Association silver level (or better) Ride Center (

www.imba.com/model-trails/ride-centers).

With regards to arts development, we find evidence of art encouraging natural capital value shifts away from extractive focus toward aesthetics and recognizing socioecological connections. Whereas mining encourages an extractive-based relationship between society and the natural world, the arts-based development draws on the natural environment to inspire creativity and connections to the landscape. The artwork itself communicates these messages to its audiences. The artists we interviewed emphasized the importance of “nature” as a subject matter and source of inspiration. In talking about the kind of work they do, they told us things like “I find that I sorta gravitate to the lake and paint nature”, and “I’m a photographer, so subject matter is here...nature … I’ll do a lot of nature photography … waterfalls, local scenes”.

Our team observed that natural capital is the major influence on the art produced in the area. Virtually all the art displayed was of an outdoor theme either depicting wildlife or nature. The artwork tends to focus on appreciating aesthetic and scenic values of the natural world as well as recognizing human connections to ecosystems. Another common theme critiques the environmental impacts of the legacy of mining in the region through images of industrial ruin. Still, more work uses local natural materials, especially copper, beach rocks, birch, and bird’s eye maple for crafting jewelry, sculpture, furniture, and frames. Altogether, the themes present in the art subtly encourage a value shift toward appreciating the natural world more for its spiritual, aesthetic, and connected ecosystem values rather than seeing it as resources to be used for human gain.

One risk to natural capital associated with the arts, in general, is that it can promote viewscape fetishism [

43] whereby people seek out, pay for, and develop the most scenic natural areas. These practices are relatively common among second homeowners and natural amenity-based migrants and retirees [

44]. As Kondo Rivera and Rullman [

45] (p. 174) find, fetishizing scenic views “protects the idyll but not the environment” as people develop sensitive natural areas for human housing and recreation. Literally, framing such scenes through artwork and showing it to audiences as desirable may only further these practices. In the Calumet case, we did not collect evidence that would indicate whether or not art development or associated viewscape fetishism are having a physical impact on ecosystems.

3.2.2. Cultural Capital

Calumet’s cultural heritage is shaped by a large number of ethnic immigrants who came to the community in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (especially Finnish-Americans) and the shared legacy of the copper mining industry. At Census 2000, 47% of Calumet residents identified their first or second ancestry as Finnish, compared to only 0.3% of people across the US. The second most common ancestry in Calumet is German (10%), followed by Italian (8%) and French (7%). Only 2% of the Calumet population identified their first ancestry as US or “American”, compared to 9% of people across the country who did so (see

Table 1). Architecture and names of commercial blocks and church buildings reflect the multiple faiths and nationalities associated with this diverse ethnic population.

The bitter labor strike of 1913 and the tragedy at the Italian Hall changed the cultural fabric of the community [

46,

47,

48]. As has been the case in other post-industrial towns, the slow and steady decline in mining employment, population (human capital), infrastructure (built capital) and financial capital which continued for at least seventy years left Calumet with a legacy of dependence on external forces for its identity and a perception that the community has limited power to shape its destiny [

4,

35]. Still, our research team observed and learned through interviews that the community retains an intense sense of pride and “sisu”-generally translated from Finnish to the general idea that the people are survivors.

Two especially strong sources of cultural capital are the historic buildings and associated mining heritage that are well documented, preserved, and interpreted through the Keweenaw National Historical Park (KNHP), which is headquartered in Calumet, and by other organizations. There are eight buildings or districts (neighborhoods) in Calumet on the National Register of Historic Properties. These properties are supported, in part, by the KNHP, which was established by act of Congress in 1992 after more than twenty years of community-based efforts to raise awareness of the national significance of the copper mining industry in the Keweenaw. The Park operates in cooperation with twenty-one heritage sites that are owned and operated by state and local governments, private businesses and nonprofit organizations. The Park’s Visitor Center and five of these heritage sites are located in Calumet and interpret the community’s heritage.

Our analysis shows that Calumet’s art scene fosters a sense of community, community identity, agency, and diversity of ideas among people who visit art spaces. In response to an open-ended question posed to art space visitors, 26% of survey respondents mentioned that First Fridays allows them to “be a part of something” and that it fosters a sense of community. Participants shared that they engage with First Fridays and the art scene because they want to be involved in something community-minded and to support the artist community and the small businesses.

The art district fosters community identity by celebrating the community’s mining legacy and ethnic heritage, but also by introducing alternative sources of community identity as an “arts district” and as a place with abundant natural resources, scenic beauty, and outdoor recreation opportunities. It is common to hear conversations in the galleries where elders and long-term residents pass on some of the history of place, such as prior use of specific buildings or how crowded the downtown used to be. Much of the art itself is based on local community identities. The mural shown in

Figure 5, for example, celebrates the cultural legacy of the Calumet community. This piece was commissioned by the Calumet Township Supervisor and it is hung in the lobby of the township office building, making it accessible to a broad audience beyond people who typically frequent art galleries. The local topics encourage audiences to consider the uniqueness, opportunities, and challenges associated with this community. Altogether, the arts district fosters the identity that while Calumet has certainly been shaped by its mining past, it is not “just an old mining town”, but that the community is also something more, that is has a future. Our team observed this line of thinking not just among arts enthusiasts, but among a variety of community residents and leaders.

The arts also foster a positive sense of agency, demonstrating that the local community can take control of its own destiny to create positive change. The very existence of the multiple art spaces which have opened in Calumet in the last fifteen years are evidence of the ability to make change. Art space visitors valued First Fridays because they were “uplifting” and “inspiring” and because they provided a “positive energy” and a “vibrant” atmosphere. Others commonly mentioned that they valued the art scene for the exposure to new ideas they got from looking at the art and engaging with others. On the other hand, our team did observe tension in the community between older visions of the community identity (strongly connected to mining and hopeful that mining would someday return) and those with alternative future visions (looking to the arts and outdoor recreation as the community’s future identity).

3.2.3. Human Capital

Outmigration from the Calumet area and limited employment opportunities have resulted in a relatively small working age population as shown by the dependency ratio (ratio of dependent population under age 18 or over age 65 to the working age population 18–64). This means that there are relatively few people in more economically productive ages to care for the relatively large number of dependents. Due in part to the large number of people over age 65, only about 58% of the population age 16 and over are in the labor force. Only 19% of adults age 25 and over have a college degree, compared to 26% statewide and 29% nationwide. One of the goals of Calumet’s arts-based development is to attract and maintain more of the younger/working age and college-educated population. Research shows that more highly educated people tend to be more likely to be interested in and attracted to the arts and to places with lively art scenes [

20,

49].

Since the development of the arts scene in downtown Calumet, the longtime population loss in the downtown core has stabilized. Population in the downtown village declined by over 18% in the 1980s (average loss of about 18 people per year) and by over 10% in the 1990s (average loss of 8.5 people per year), but only by 2.5% in the 2000s when the art district was developed (US Census Bureau, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010 [

38]). This correlation does not necessarily mean that arts development was the most important factor in stemming population loss- there certainly could have been other contributing factors and the speed of decline had slowed even in the 1990s before the arts development was underway. It could simply be that those who had the means or inclination to leave had already done so before 2000. Still, the interviews and surveys we reviewed suggest that the arts district is one factor that is attracting some people to the community and keeping some existing residents in place. The combination of affordable housing and a vibrant art community makes Calumet an attractive location for artists and a place where some can make a living doing art. As a one artist we interviewed explained:

“I hope that I can always make work that challenges me and that I can make a living doing it that way. That’s part of why I moved here, I guess, because the cost of living here is much less for me and I don’t have to compromise necessarily what I want to make.”

The art district provides at least partial employment and/or supplemental income to a growing number of artists and entrepreneurs. One painter we interviewed explained that before First Fridays started and the art scene in Calumet really started to coalesce, he only sold one or two paintings a year, but now he has sold out a number of shows and he has a regular source of income through art. A ceramic artist described her ability to make a living from art in Calumet as challenging but doable given the general affordability of living in the community. She says:

“I have a line of functional work that tends to be more saleable and that brings in more money and I also make some sculpture and do some painting that is more my kind of personal work. The majority of my work, when I sell it, tends to be kind of ‘events’. I’ll … have a big opening and usually the show will then, you know, kind of sell out, and that has happened up here in Calumet in a couple of the different shops. You know everything is relative, so you know making a thousand dollars on a Friday night in this venue, is very different than where I moved from. You know, it’s like a month’s worth of wages (laugh).”

The arts also provide an opportunity to be productive for several of the senior residents of the Calumet community. For example, the Copper Country Associated Artists cooperative includes about 30 members who are over the age of 62 (75% of total membership). The team learned through interviews that several of these seniors rely on art sales for supplemental income. Given the high dependency ratio in the community, having this opportunity to remain economically productive in later years could potentially reduce some strain.

Dozens of artists show and sell their work in Calumet’s art spaces each year. Interviews with gallery managers revealed that approximately 45 artists participate in the Copper Country Associated Artists cooperative, about 75 different artists show work at the Paige Wiard Gallery each year, about 10–15 artists exhibit each year at Galerie Boheme and another 15 exhibit at the Calumet Art Center. Yet, most artists in Calumet do not rely on art as their main income, and those who do create utilitarian or functional art that is more likely to sell in addition to art that is more of a critique or process piece. The professional artists we spoke with noted that they are only able to make a moderately viable income selling art that is not consistent or secure. Many also teach art and/or have other jobs to supplement their income. Because of a weak local economy, Calumet must rely on summer tourism and occasional events that attract people from extended communities to sell art.

There is also some potential for job creation in building restoration and revitalization efforts that are inspired by demand for art spaces. There are several examples our research team heard about in the course of this study. Galerie Boheme is located in a building that was vacant and in need of repair before the current owner purchased it and restored it as an art gallery and workspace with living quarters upstairs. Similarly, the remodeling of the Omphale Gallery was the vision of one artist who hired local contractors and carpenters to remodel the first floor space into a gallery and café. A local photographer recently purchased a building on Fifth Street and is using local contractors for the electrical work. A local developer who recently rehabilitated the former Morrison School into apartments rents prime space to an artist for gallery/studio space.

The arts district also builds and rewards skills in making. As one artist we interviewed described, “I think there is a whole movement to buy local, to buy handmade. People want a different experience, not something that is mass produced, and I’m totally behind that.” She was referring to the fact that artists can hand-make items that are in demand, and arts districts provide opportunities for people to develop those skills and talents. The Calumet Arts Center is built around this philosophy. They opened in 2008 in an old church building and focus on offering art classes in claywork, painting, print, weaving, and glass beads primarily to children, but also to adults. Approximately 60 middle and high school students participate each week in art classes as well as 75–100 adults who take classes each year through the center. Each year, 8–12 different artists instruct classes through the center and about 15 different artists exhibit there. They also offer a mentoring program that partners emerging artists or artists who want to learn new skills with established and expert artisans. The center reaches out to low-income, veterans, and tribal community members through partnerships with the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community. Copper Country Associated Artists also seeks to build skills offering hands-on arts experiences each month during First Fridays free of charge to the public and attracting between 20 and 75 participants each month.

3.2.4. Social Capital

“Social capital refers to features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and trust, that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” [

50] (p. 35). Social capital is one of Calumet’s strengths and residents are proud of the work they accomplish by coming together to support various initiatives. Violent and property crime rates are low (a quarter to a half of the state and national averages, as shown in

Table 1). Volunteering and collaboration norms are strong, and community social organizations are prevalent and active.

There are multiple organizations, clubs and volunteer groups that do community or charitable work. For example, Main Street Calumet, a grassroots organization aimed at revitalizing the downtown district, partners with the village administration, the Downtown Development Authority (DDA), the Keweenaw National Historical Park and Calumet Township to help organize community improvement projects. Main Street has about 10–15 core volunteers who put in hundreds of hours each year plus another approximately 50 volunteers who help with special events. The Swedetown Trails Club, a volunteer organization with over 400 members, helps maintain and pay for grooming cross country ski trails near downtown Calumet. The Calumet Lion’s Club recently raised $15,000 and donated hundreds of volunteer hours to help Calumet Township develop a barrier free walking path, disc golf and picnic area at Calumet Lake. The Copper Country Curling Club raised $32,000 in matching funds to make improvements to the former mining company shop which they use for indoor curling. The Copperdog150 dogsled race event uses about 600 volunteers annually to support a dogsled race that attracts thousands of spectators to Calumet. The Calumet Hockey Association member/players pay for ice time and the operation of the ice rink at the Calumet Colosseum. The Rotary, Calumet Lodge 404 Elks, and other groups raise money for local scholarships and other charitable work. These are just a few examples (not exhaustive) of the organizations that help provide recreational, cultural, and professional opportunities that attract visitors and residents to the area that the village and the township would not otherwise be able to afford.

Collective organizations associated with the arts include the Copper Country Associated Artists cooperative (CCAA), the Calumet Art Center, and the Calumet Arts District. CCAA is a 45-member organization that maintains gallery space, puts on public demonstrations or activities each month, provides a social network for its members, and promotes the arts. The cooperative is a non-profit organization funded by member dues, gallery commissions on member art sales, and from vendor fees (fees for service) from its annual juried art show. Decisions are made democratically- some are made by an elected board that meets monthly, but most decisions are made collectively by member vote. The main purpose of the CCAA is to “support artists and the community”. The Calumet Art Center is a non-profit 501 C3 with a primary focus on arts education (especially traditional arts, culture and history) and reaching out to diverse publics to promote involvement in the arts. It is funded primarily through memberships, grants, and donations, but also from fees for service (art classes, performance hall fees) and art sales. The art center is managed by an Executive Director who oversees daily activities with a limited staff and volunteers, and reports to a board of directors who oversee the operation. The Calumet Arts District is a newer and loosely formed group that organized with the aim of coordinating efforts across the various art spaces in Calumet and promoting Calumet as an arts community. It does not have a budget, and decisions are made collectively using a consensus model.

It is important to consider the impact of the arts on both bonding and bridging social capital. Bonding describes connections among close-knit individuals and groups who typically share a common background. Scholarship suggests that such bonds among residents empower them to protect and pursue their collective interests [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Yet, bonding social capital can exclude individuals or groups and divide communities along economic, race, age, or other cultural lines [

55,

56]. In order to promote

inclusive networks, bonding social capital must be balanced with bridging social capital [

15,

16,

51,

52,

57]. Bridging social capital connects diverse and different groups within the community to each other and to other groups outside the community [

51]. Bridging occurs when members of one group connect with members of another group to access support or gain information [

52].

Calumet’s art activities serve as a catalyst for both bonding and bridging social capital and the various art spaces serve as “third places” (social gathering places outside of home and work) where people can connect [

58]. First Fridays facilitate bonding by bringing similar groups of people together in a common space to socialize. A very consistent theme among the people we spoke with was that First Fridays are as much of a social event as an art event. This was an important point that people wanted to emphasize. One artist we interviewed explained that First Fridays are “something to do, hopefully its somewhere you’ll see people, kind of celebrate what’s going on”. Another Calumet resident spoke of First Fridays saying: “It’s a vibrant event and gives area artists a chance to connect with the public. Everyone I know really appreciates this monthly opportunity. It also gives a ‘meeting place’ venue for art aficionados and folks coming for the first time to gather and share comments and meet the artists and new people”. This illustrates the importance of the space for building this kind of bonding social capital, bringing together people with similar interests on a regular occasion.

Most of the First Friday’s visitors (73%) surveyed had previously attended the event. They often knew each other, the art space owners/managers and the artists who exhibited there. This created an overall atmosphere of familiarity, but one that could be exclusive to people who are not already insiders. For instance, one member of the research team observed that “once inside [the gallery] it became very apparent that everyone knew each other and you felt like you were interrupting something”. This is one example of how the Calumet arts district forms boundaries that can serve as a deterrent for new individuals to feel comfortable. Several observations indicated that there was a real or perceived boundary between the visitors to First Fridays and the wider Calumet community. Another participant observed that “the artists are a little bit uppity and people who aren’t artists feel excluded from the First Friday experience”. This boundary was partially formed as a result of the somewhat narrow appeal of art to the wider community and also the observation that many people already knew each other at the First Fridays events. Another First Friday regular remarked that they are “sort of stagnant” with the same people attending all the time and needing “some new life to them”. Several observations remarked on the lack of young people frequenting the art district—75% of visitors we surveyed were over the age of 50. Still, all of the observers in the research team (most of whom were young adults in their 20s) articulated a consistently positive social atmosphere and a sense of feeling welcome at all of the art spaces.

Despite the somewhat insular nature of the bonded social capital observed, First Fridays also created positive bridging social capital. First Fridays helped draw different groups of people to Calumet. Survey data indicated that 27% of visitors to First Fridays were visiting for the first time and that the majority of visitors were actually from outside of the immediate Calumet area, with the majority being from the Houghton/Hancock area (37%). Moreover, many of the artists in Calumet have lived elsewhere around the country at some point in their lives and maintain connections with distant art organizations and widespread social networks. Tourists are also attracted to the art scene and draw new types of people with different networks into the community. In these ways, the emerging art district in Calumet appears to be bridging different groups, organizations, and individuals together through weak, but important networks [

59].

Altogether, the data suggest that Calumet’s art district is strengthening close ties among people engaged in the arts and who regularly attend First Fridays and visit the galleries. It is bringing together similar people to socialize on a regular basis and help them to identify common interests and to share community interests. It is also helping to establish some weaker networks (bridging) between residents of the broader region, tourists, newcomers, seasonal residents, and art-related organizations and actors from across the country and around the world. However, the same bonded relationships present a challenge for First Fridays in that they can lead some (new people or different people) to feel excluded from the art scene. The art scene does not appear to be adequately bridging social capital between different social groups within the local community. From our observations there appears to still be the folks who engage with First Fridays and the folks who do not, with younger people and lower income people mostly left out of the art scene (with some exceptions, especially those promoted by the Calumet Art Center).

3.2.5. Political Capital

Political capital is about the inclusion of different voices in the community and the ability to get things done, make decisions locally, and enforce codes. Calumet, like many post-industrial towns, was left with a legacy of dependence on external forces (e.g., C & H Mining Company, Jasper, AL, USA) and the perception that the community has limited political power to shape its own destiny. The community continues to suffer from a certain degree of acquiescence to the status quo [

4]. The Calumet Township Board of Trustees have all served for several years, all identify with the same political party, and have run unopposed for the past several elections. The same Township Supervisor (elected position) has served the community for 43 years. There is little diversity of voice in the governance of this community and there are relatively few residents who are willing to run for office. This is particularly true in the downtown core area, which is administered as the Village of Calumet. Those who are willing to get involved sit on multiple committees and boards.

Voter turnout in the broader Calumet area is similar to the US national average (about 59% in the 2012 presidential election), but within the downtown Calumet core area (Village), turnout is lower at 44% [

60]. The Village of Calumet Civic and Commercial Historic District and Ordinance was established in 2002. The Village recently made changes to its historic district ordinance to address “demolition by neglect” but does not have a minimum maintenance standard and struggles to enforce its ordinances. The administration does not have the financial ability to hire someone to enforce a minimum maintenance standard or to bring violators into compliance.

Still, some people with different or new ideas have been able to get traction and make change in the community often working behind the scenes or not directly through formal leadership structures. One example is in the establishment of the Keweenaw National Historical Park (KNHP). After the mines closed in 1968, many of the historic mining buildings were repurposed or lost to abandonment, fires or the wrecking ball. One of the most poignant losses occurred in 1984 when the Calumet Village Council voted to demolish the Italian Hall, the site of the Christmas Eve tragedy in 1913. The building had fallen into disrepair after years of neglect. A group of concerned citizens made an effort to stop the demolition, but failed to raise enough funds to save the building. The demolition of the Italian Hall was a catalyst for a renewed effort to save what remained of the community’s architectural and mining legacy. A grass-roots group formed in 1987, to lead an effort to establish a national park in Calumet. After years of community driven effort, the Keweenaw National Historical Park was established on 27 October 1992 [

61].

The development of the arts district itself resulted from an artist in the community who saw the vacant downtown and buildings in disrepair and felt that something must be done to revitalize the community. He saw an opportunity for the arts and worked through his own private funds, personal initiatives, and social networking to start opening galleries and other art spaces.

Today, the art scene challenges the current political structure in Calumet in three ways. First, art is a medium through which people (even relatively powerless people such as low income children taking art classes at the Calumet Art Center) can find, express, and communicate their own voice. Sometimes the art created makes a political critique and can be an avenue through which people can raise their concerns and/or challenge existing systems. Teaching people to find this voice through arts education (e.g., at the Calumet Arts Center and the CCAA) and exhibiting work from a variety of artists in galleries across the community are ways that the arts district is opening up space for multiple voices that may not otherwise have any public hearing. Several artists we interviewed remarked on how unique the art scene in Calumet is because it is not hard to get shows or exhibit space. You do not have to be a highly established artist to get your work seen in public. This fact opens the door to less powerful groups to share their ideas through art, and it may be a common characteristics in shrunken cities.

Second, First Fridays allows artists and those who regularly attend and engage with the art scene to gain some political capital as a group they may not otherwise have as individuals. The monthly nature of First Fridays has provided a regular social venue which allows for the exchange of ideas and social connections among artists, art space owners, and tourists. One initiative that has come out of the regular interaction at First Fridays has been an effort to improve the downtown windowscapes in both occupied and vacant buildings. Our team observed that a regular topic of discussion at First Fridays events is on the state of disrepair or blight in the downtown. In light of these discussions, two artists decided that one way they could make a difference would be to stage windowscapes across the communities with a “windows into the past” effort. Many downtown buildings were full of storage or trash or boarded up. The artists brought their idea to the KNHP and partnered with the local school and businesses to research past uses of downtown buildings, make posters explaining their history, and then decorate windows to show the posters and antiques to create an image of the past. The effort has been successful and, as one of the artists who worked on the project explained, “it is definitely something that has changed the atmosphere downtown. Everybody comments on that. Some of those buildings that have been vacant and for sale for years, sold after we did that. I think it might have made a difference”.

Finally, the development of multiple galleries and art spaces throughout the downtown area has created a new power base with different interests and led by a different group of people in comparison to the more traditional and long-time community leaders in this community, many of whom still have ties to the mines and related businesses that were prominent in the community in the early twentieth century. These leaders are not directly or officially incorporated into governance structures, but they do constitute a political voice that requires some attention. In Calumet, the development of the arts district was homegrown and small scale. It is locally controlled and demonstrates a shift away from relying on external corporatism to community residents with relatively few resources shaping their own futures. The result is the beginning of a more pluralist set of interests and voices in community leadership and a growing sense of agency and independence in the community.

Despite these opportunities, coordination among the various arts-related groups is not well developed and collaboration between galleries has been challenging without a clear leadership or organizational structure. To begin to address these issues, the Calumet Arts District was formed in 2013 to promote the visual arts, bring the various galleries and art spaces together in order to better promote the district as a whole, share costs for advertising, create a more organized effort for First Fridays and discuss issues related to the downtown and the art scene in Calumet. Since 2013, the group has created a rack card and map listing all of the art spaces, collaborated on group advertising, and created lively yellow flags which identify the art spaces during events like First Fridays. The group is currently working towards a more organized structure, and is refining its definition of art gallery/art space and developing an annual advertising budget.

While the arts make space for political critique and organizing for change, political action for community change or leadership among artists and art enthusiasts, outside of clearly arts-related activities, has been minimal or nonexistent. In addition, despite the grassroots agency involved in developing the arts district, its success remains dependent upon outside forces, now in the form of tourists, visitors from nearby communities, and seasonal residents.

3.2.6. Built Capital

One of Calumet’s most defining characteristics is its rich architectural heritage in the historic downtown area, which is designated a National Historic District. Most of the built infrastructure dates to the early-twentieth century when Calumet was a vibrant and growing city with tens of thousands of people in the local area and a great deal of wealth. The infrastructure was built to serve a city of 50,000–100,000 residents [

35]. Many of the downtown buildings are comprised of a beautiful and highly sought after reddish-colored Jacobsville Sandstone, quarried in the region. Calumet also has distinctive historic homes built by mining executives, the Calumet Theatre, and numerous other historic structures. Most of the housing stock (73%) was built before 1940 (see

Table 1).

Historic buildings pose both challenges and opportunities. Architectural heritage encourages tourism and political efforts to help preserve the unique historical legacy. The buildings connect the community to its past and offer a sense of identity and uniqueness. Yet, many of these historic structures are uninhabited and in danger of collapse due to a combination of deferred maintenance, extreme winter temperatures and heavy snow, and expensive heating costs. The loss of buildings to abandonment and neglect decreases the tax base and the municipality’s ability to provide services.

Property values are low and a large proportion (24%) of homes are vacant. According to the American Community Survey (2009–2013), 84% of owner occupied housing units in the downtown Village are valued at less than $100,000. Low property values further limit municipal ability to generate tax revenue. On one hand, the community does not want to part with their properties. On the other hand, they do not have sufficient economic and financial resources to maintain them. The result is a vicious cycle where historic buildings are valued, but not preserved because of lack of funds.

Artists have been instrumental in restoring and preserving some of Calumet’s historic buildings, stabilizing and restoring them to serve as commercial or non-profit art spaces. Most of the current art spaces are located in historic buildings that were in need of rehabilitation. The buildings are more than simple infrastructure: they are part of the art itself. For instance, the Calumet Art Center is located in a historic church. Because the buildings that artists have restored are clustered in the downtown core near one another, the collection of restored historic buildings serves as a valuable community legacy that contributes to community identity. The buildings are witnesses of the past and communicate the community’s heritage to residents and visitors.

At the same time, arts-based development of low-value, yet historically desirable buildings raises concerns for the potential of gentrification to price low-income residents out of the housing market. Despite very low property values (see

Table 1), housing affordability remains a struggle in Calumet because of low incomes and lack of updated, safe, accessible housing. Housing cost burden is high with an estimated 60% of renters spending 30% or more of their income on housing costs in the broader Calumet area (63% in the downtown Village), in comparison to 52% of renters who spend this much nationwide [

41]. Affordable, quality housing is in high demand; but in the data we collected, we found no indication of arts-based gentrification pricing people out. The impact of the art district has simply not raised values, given the large number of vacant properties and old buildings that are available in this city that was built for a population ten times its current size. If anything, the arts district has increased the amount of affordable housing available in the downtown by providing some incentive for developers to restore buildings with apartments in the upper floors and store fronts in the lower levels, rather than to simply allow these spaces to decay. Our team interviewed two local developers each of whom recently remodeled historic buildings in downtown Calumet for high-quality affordable rental housing. The emerging art scene is one of several factors that make their investment worthwhile.

Beyond historic buildings, built capital encompasses broad sets of infrastructure including roads, utilities, water systems, and other physical structures. As in other shrunken cities, Calumet’s infrastructures is aging, suffering from poor maintenance, and is overbuilt. We did not uncover any evidence that arts-based development has had any impact on built capital development other than with regards to historical buildings.

3.2.7. Financial Capital

Financial sustainability is one of Calumet’s biggest challenges both in the public sector as well as for many residents and businesses. An estimated 21% of Calumet area residents fall below the poverty line (see

Table 1). In the downtown core the poverty rate is substantially higher at 48%, compared to the state of Michigan total at 17%. Median household incomes are significantly below state or national figures. Housing values are low (median values are about 50% of the state median) and this, along with population decline, reduces the tax base for municipal governments. Moreover, because of the small population and low-income, there is little incentive for new businesses or financial institutions to invest in the community.

Calumet’s downtown businesses are vital to the local economy. With few exceptions, the downtown cafés, restaurants, galleries, and businesses are unique and locally owned and operated. These businesses bring in dollars from outside the area (tourists) as well as helping keep local dollars in the community encouraging people to buy local. The arts district brings customers into the community and raises awareness about the businesses in Calumet. Several comments from gallery owners and art space visitors in our surveys and interviews indicated that First Fridays are an important community event that brings visitors back into the downtown shops and cafés even if they do not buy anything that very evening, they sometimes come back and purchase later.

In addition, the arts scene has spurred significant public and private investment in Calumet over the past several years, including the opening of several private and non-profit galleries in the downtown. Most of the art spaces are operated with private funds, bring some level of employment into the downtown. These businesses have also brought degraded buildings or buildings that had been tax-forfeited back onto the tax rolls. Several art spaces contribute to the local economy by providing affordable housing (upstairs) for residents, artists and visitors. The Paige Wiard Gallery, Café Rosetta, Cross Country Sports, Galerie Boheme, Artis Books, and a new photography gallery all have apartments on the upper floors which provide housing.

Based on our team’s observations, the informal economy does appear to be active in Calumet. This seems to revolve around paying cash for goods or services such as childcare, construction work, or firewood. There is also some level of trading, and one artist mentioned in an interview that she was able to trade art for vegetables and other needs at times. Because this was not the primary topic of our investigation, we have only limited information about the informal economy.

All told, given the degraded tax base, the overbuilt and aging infrastructure, and the low income and high needs in this community; the financial capital generated from the current arts scene helps but is not enough to meet the challenges.

3.2.8. Summary of Results

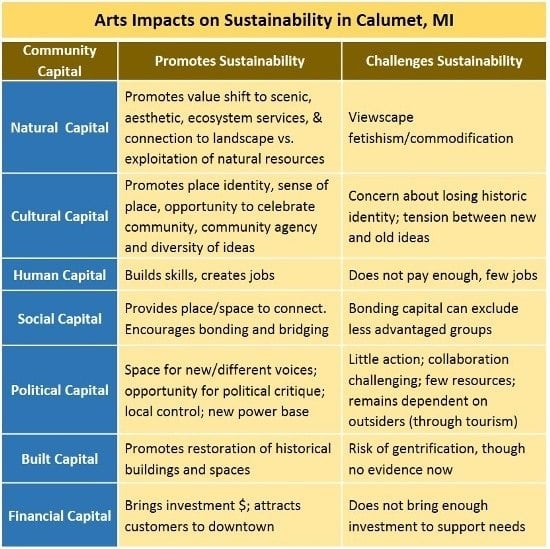

Altogether, the arts district promotes each of the seven community capitals in key ways, but it also introduces important challenges (see

Table 2). Given the particular challenges and opportunities associated with the shrunken city context (especially vacant downtown buildings, affordable rents, degraded tax base, and aging and overbuilt infrastructure); the arts district in Calumet promotes a sustainable future by allowing people to see an alternative, hopeful, and vibrant path forward. The arts have been instrumental in helping give the community an emerging new identity as a unique community that has a future in art, outdoor recreation, and connections to heritage landscapes. This identity challenges competing visions of the community as a “worn-out old mining town” that was built by and remains dependent on mining and that is gradually crumbling away.

This kind of hope and place attachment is critical for Calumet’s future. The Village Administrator who said that he sees outdoor recreation and arts as two key paths toward Calumet’s future, explained:

“I can see the potential here. There is some positivity. Therefore, much potential. We got to try to get away from the infighting. People are saddened by the current state of the community and if we can see some positivity, people will come out and support us. They want that … You can look at our downtown and it’s got such cool facades. Property is cheap. We want to bring some vibrancy back to downtown. But you’re not going to get a quick flip. The buildings might not be worth anything now, or you might be able to purchase one for a few thousand dollars, but it will take a couple hundred thousand just to get it stable. You’re not going to see the economic return in your lifetime. You’ve got to have people to fall in love with the area and invest. You have to find someone who will do it for the love of the place”.

The arts district, as well as the outdoor recreation opportunities and the uniqueness of place might just provide the type of community identity that will get people (residents, second-homeowners, and even visitors) to fall in love with the community. Several of the artists we interviewed spoke of just this kind of process, when deciding to relocate to Calumet.

Yet, despite its successes, the arts district has not been able to stop the decline in tax base, employ sufficient numbers of people, reduce poverty, or otherwise do much to help the large number of low-income people to get their basic needs met. These are serious critiques. There are also concerns with exclusion of less advantaged groups from close-knit social capital networks and the fact that there has been relatively little political involvement or directed initiatives among the arts groups except for pushing for activities that are clearly related to the arts or to restoring historical buildings or reducing blight.