Forgotten Nazi Forced Labour Camps: Arbeitslager Riese (Lower Silesia, SE Poland) and the Use of Archival Aerial Photography and Contemporary LiDAR and Ground Truth Data to Identify and Delineate Camp Areas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Historical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.1.1. The Wolfsberg Labour Camp

3.1.2. The Kaltwasser Labour Camp

“The Kaltwasser camp was a camp where 2000 Jews from Auschwitz came to work”.[32]

3.1.3. The Dörnhau Labour Camp

“Prisoners from nearby camps were all put together in Dörnhau, to work constructing railroads. They were located in a separate camp”.[33]

3.1.4. The Säuferwasser Labour Camp

3.1.5. The Wüstegiersdorf Labour Camp

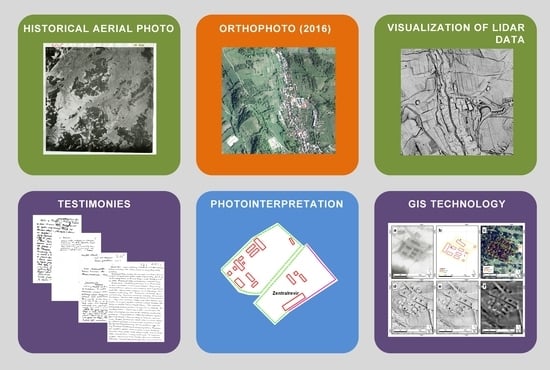

3.2. Spatial and Additional Data

3.3. Data Processing

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Data Integration and Photointerpretation

4.1.1. Wolfsberg Labour Camp

4.1.2. Kaltwasser Labour Camp

“Four long buildings with big windows and glass doors were surrounded by a wire fence. Apart from buildings numbered from 2 to 5, there was also a kitchen there”.[45]

“The camp was different from Auschwitz. Four long buildings with big windows and glass doors. Surrounded by razor wire fence. Apart from buildings with rising numbers, there was also a kitchen there”.[45]

4.1.3. Dörnhau Labour Camp

4.1.4. Säuferwasser Labour Camp

4.1.5. Wüstegiersdorf Labour Camp

4.2. Field Survey of the Remains of the Forced Labour Camps

- (1)

- The lack of specific plans of camps is visible on the layout of the structure and foundation of its elements (e.g., Figure 3 and Figure 9). The camp facilities are located randomly and against their functionality and operational safety. Camp kitchens and food warehouses, as well as the baths, are often situated in low grounds and morasses. Camp baths were located as close as possible to streams or surface intakes (common in depressions) of water, not taking into account sewage outflows (corresponding slopes). The camp barracks were placed not in regular rows at appropriate intervals but tightly in favorable terrain, which adapted to the needs of the camp at the lowest cost of the work done.

- (2)

- The lack of proper load-bearing walls and low quality of concrete structures were observed (Figure 4). Exterior walls with a height of 1 to 1.5 meters made of brickwork having a thickness of 25 to 40 cm; the cement-lime mortar layer is uneven and varies from 1 to 3 cm thick. Partitions were made from a single brick wall. Concrete constructions lacked steel reinforcements. The concrete mix contained ill-sorted aggregate composed of local rocks: Carboniferous gravel (weathered Carboniferous conglomerate) and broken fragments of Neogene basalts.

- (3)

- (4)

- The primary building materials for building the most of the camp facilities were mortar-bonded bricks and wooden elements (recently not present). The red ceramic brick (Figure 4) was bonded using mortar made of cement mixed with lime and ill-sorted aggregate. Not less than 20% of bricks came from recycling (demolition). The recycled bricks were poor quality and in bad condition of using.

- (5)

- No traces of plastering were found (Figure 4).

- (6)

- Freestanding chimneys (Figure 16) built without foundation footing and internal reinforcement, no refractory brick inside.

- (7)

- Lack of installation elements of metal plumbing.

- (8)

- Camp prisoners used raw water collected from neighboring streams and ponds rather than water wells. No traces of water treatment installations have found during archival research as well as a field survey.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pettitt, J. Introduction: New perspectives on Auschwitz. Holocaust Stud. 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schute, I. De vuilstort van Kamp Westerbork, Gemeente Aa en Hunze; RAAP Archeologisch Adviesbureau, B.V.: Weesp, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, D.; Colls, C.S. A multi-level and multi-sensor documentation approach of the Treblinka extermination and labor camps. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 34, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karski, K.; Różycki, S.; Schwarz, A. Memories of Recent Past. Objectives and Results of Non-invasive Archeological Research Project at KL Plaszow Memorial Site. Analecta Archaeol. Ressoviensia 2017, 12, 221–246. [Google Scholar]

- ‘Forgotten’ Nazi Camp on British Soil Revealed by Archaeologists. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2020/03/forgotten-nazi-camp-british-soil-revealed-archaeologists (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Jasinski, M.E. Predicting the past—Materiality of Nazi and post-Nazi camps: A Norwegian perspective. J. Histor. Archaeol. 2018, 22, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, R.; Olsen, B.; Petursdottir, Þ.; Witmore, C. Teillager 6 Sværholt: The Archaeology of a World War II Prisoner of War Camp in Finnmark, Arctic Norway. Fennosc. Archaeol. 2014, 31, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Różycki, S.; Michalski, M.; Kopówka, E. Obóz Pracy Treblinka I: Metodyka Integracji Danych Wieloźródłowych; ELPIL, Faculty of Geodesy and Cartography: Siedlce, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Early, R. Excavating the World War II Prisoner of War camp at La Glacerie, Cherbourg, Normandy. In Prisoners of War; Mytum, H., Carr, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Colls, C.S. Holocaust Archaeologies: Approaches and Future Directions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colls, C.S. Holocaust archaeology: Archaeological approaches to landscapes of Nazi genocide and persecution. J. Conflict Archaeol. 2012, 7, 70–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, A.; Addis, M. Memorialization and the ecological landscapes of Holocaust sites: The cases of Plaszow and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schute, I. Collecting artifacts on Holocaust sites: A critical review of archaeological research in Ybenheer, Westerbork, and Sobibor. Int. J. Histor. Archaeol. 2018, 22, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antkowiak, M.; Völker, E. Dokumentiert und konserviert. Ein Außenlager des Konzentrationslagers Sachsenhausen in Rathenow, Landkreis Havelland. Archäologie Berl. Brandenbg. 2000, 1999, 147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, G.; Colls, C.S. Taboo and sensitive heritage: Labour camps, burials and the role of activism in the Channel Islands. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mineo, S.; Pappalardo, G. Sustainable Fruition of Cultural Heritage in Areas Affected by Rockfalls. Sustainability 2020, 12, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.-J. Flood risk maps to cultural heritage: Measures and process. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropáček, J.; Neckel, N.; Tyrna, B.; Holzer, N.; Hovden, A.; Gourmelen, N.; Hochschild, V. Repeated glacial lake outburst flood threatening the oldest Buddhist monastery in north-western Nepal. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicu, I.C.; Stoleriu, C.C. Land use changes and dynamics over the last century around churches of Moldavia, Bukovina, Northern Romania—Challenges and future perspectives. Habitat Int. 2019, 88, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y. Establishing cooperation between Israel and Poland to save Auschwitz Concentration Camp: Globalising the responsibility for the Massacre. Int. J. Tour. Pol. 2007, 1, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochałek, A.; Jabłoński, M.; Lipecki, T.; Jaśkowski, W. Methodology of historical underground objects inventory surveys–contribution. Geoinform. Pol. 2018, 17, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutterman, B. A Narrow Bridge to Life; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stach, E.; Pawłowska, A.; Matoga, Ł. The Development of Tourism at Military-Historical Structures and Sites–A Case Study of the Building Complexes of Project Riese in the Owl Mountains. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2014, 21, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kajzer, A.; Ostoja, A. Za Drutami Śmierci; Wydawn: Łódzkie, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Jabłoński, M.; Lipecki, T.; Jaśkowski, W.; Ochałek, A. Virtual Underground City Osówka. Geol. Geophys. Environ. 2016, 42, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sula, D. Arbeitslager Riese: Filia KL Gross-Rosen; Muzeum Gross-Rosen: Wałbrzych, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Secrets of the Sowie Mountains, Vol I–IV. Available online: http://www.warsawvoice.pl/WVpage/pages/article.php/2878/article (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Kryza, R.; Fanning, C.M. Devonian deep-crustal metamorphism and exhumation in the Variscan Orogen: Evidence from SHRIMP zircon ages from the HT-HP granulites and migmatites of the Góry Sowie (Polish Sudetes). Geodin. Acta 2007, 20, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megargee, G.P. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. 1933–1945; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brion, P. REIMAHG, Geschichte in Bildern—REIMAHG—A Pictorial History; Eigen Verlag: Kahla München, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blatman, D. The Death Marches: The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Testimony of the Former Prisoner Moniek Kaufman, Sign; 301/1939; The Jewish Historical Institute in Poland: Warsaw, Poland.

- Testimony of the Former Prisoner Norbert Szeinowicz, Sign; 301/1939; The Jewish Historical Institute in Poland: Warsaw, Poland.

- Sula, D. Na Granicy Życia i Śmierci. Biografistyka Pedag. 2017, 2, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elmanowska, B. Abraham Kajzer i jego tekst z obozów koncentracyjnych–studium przypadku. Autobiografia. Literatura. Kultura. Media 2015, 4, 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- 950 Interviews aus der Sammlung der USC Shoah Foundation. Available online: http://transcripts.vha.fu-berlin.de/ (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Bożek, P.; Janus, J.; Mitka, B. Analysis of Changes in Forest Structure using Point Clouds from Historical Aerial Photographs. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Affek, A. Georeferencing of historical maps using GIS, as exemplified by the Austrian Military Surveys of Galicia. Geogr. Pol. 2013, 86, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.T.; Gonçalves, J.A.; Beja, P.; Pradinho Honrado, J. From archived historical aerial imagery to informative orthophotos: A framework for retrieving the past in long-term socioecological research. J. Remote Sen. 2019, 11, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurczyński, Z. Fotogrametria, 1st ed.; PWN S.A.: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sevara, C.; Verhoeven, G.; Doneus, M.; Dragantis, E. Surfaces from the Visual Past: Recovering High-Resolution Terrain Data from Historic Aerial Imagery for Multitemporal Landscape Analysis. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2018, 25, 611–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kokalj, Ž.; Hesse, R. Airborne Laser Scanning Raster Data Visualization: A Guide to Good Practice (Vol. 14); Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovakia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kokalj, Ž.; Zakšek, K.; Oštir, K.; Pehani, P.; Čotar, K.; Somrak, M.; Kokalj, Ž. Relief Visualization Toolbox, ver. 2.2. 1 Manual. Remote Sens. 2016, 3, 398–415. [Google Scholar]

- Doneus, M. Openness as Visualization Technique for Interpretative Mapping of Airborne LiDAR Derived Digital Terrain Models. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6427–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colls, C.S.; Colls, K. Reconstructing a Painful Past: A Non–Invasive Approach to Reconstructing Lager Norderney in Alderney, the Channel Islands. In Visual Heritage in the Digital Age; Ch’ng, E., Gaffney, V., Chapman, H., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2013; pp. 119–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zalewska, A. The ‘gas-scape’ on the eastern front, Poland (1914–2014): Exploring the material and digital landscapes and remembering those ‘twice-killed’. In Conflict Landscapes and Archaeology from Above; Stichelbaut, B., Cowley, D., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2016; pp. 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wroniecki, P.; Jaworski, M.; Kostyrko, M. Exploring free LiDAR derivatives. A user’s perspective on the potencial of readily available resources in Poland. Archaeol. Pol. 2015, 53, 611–616. [Google Scholar]

- Witharana, C.H.; Ouimet, W.B.; Johnson, K.M. Using LiDAR and GEOBIA for automated extraction of eighteenth—Late nineteenth century relict charcoal hearths in southern New England. GISci. Remote Sen. 2018, 55, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusiniak, M. Obóz Zagłady Treblinka II w Pamięci Społecznej (1943-1989); Neriton: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Góralski, M.W. Polish-German Relations and the Effects of the Second World War; Polish Institute of International Affairs: Warszaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemi, A. Expropriation of Foreign Property in International Law. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Hull, Hull, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Madej, J.; Łój, M.; Porzucek, S.; Jaśkowski, W.; Karczewski, J.; Tomecka-Suchoń, S. The geophysical truth about the ‘Gold Train’in Walbrzych, Poland. Archaeol. Prospect. 2018, 25, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsz Śmierci. Available online: https://www.goryponadchmurami.pl/2011/08/marsz-smierci.html (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Różycki, S.; Kopówka, E.; Zalewska, N. Obóz zagłady Treblinka II. Topografia Zbrodni; Wydział Geodezji i Kartografii PW, Elpil: Siedlce, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamola, A.; Różycki, S.; Bylina, P.; Lewandowski, P.; Burakowski, A. Forgotten Nazi Forced Labour Camps: Arbeitslager Riese (Lower Silesia, SE Poland) and the Use of Archival Aerial Photography and Contemporary LiDAR and Ground Truth Data to Identify and Delineate Camp Areas. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12111802

Kamola A, Różycki S, Bylina P, Lewandowski P, Burakowski A. Forgotten Nazi Forced Labour Camps: Arbeitslager Riese (Lower Silesia, SE Poland) and the Use of Archival Aerial Photography and Contemporary LiDAR and Ground Truth Data to Identify and Delineate Camp Areas. Remote Sensing. 2020; 12(11):1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12111802

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamola, Aleksander, Sebastian Różycki, Paweł Bylina, Piotr Lewandowski, and Adam Burakowski. 2020. "Forgotten Nazi Forced Labour Camps: Arbeitslager Riese (Lower Silesia, SE Poland) and the Use of Archival Aerial Photography and Contemporary LiDAR and Ground Truth Data to Identify and Delineate Camp Areas" Remote Sensing 12, no. 11: 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12111802

APA StyleKamola, A., Różycki, S., Bylina, P., Lewandowski, P., & Burakowski, A. (2020). Forgotten Nazi Forced Labour Camps: Arbeitslager Riese (Lower Silesia, SE Poland) and the Use of Archival Aerial Photography and Contemporary LiDAR and Ground Truth Data to Identify and Delineate Camp Areas. Remote Sensing, 12(11), 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12111802