Hyperspectral Sensors as a Management Tool to Prevent the Invasion of the Exotic Cordgrass Spartina densiflora in the Doñana Wetlands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Hyperspectral Images

3.2. Atmospheric Correction and Data Reduction

3.3. Spectral Target Detection Algorithms

- Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM): SAM is a widely used spectral similarity measure in remote sensing and has been used for plant species discrimination [20,25,35,36,56,57,58,59]. This algorithm estimates the similarity between two spectra by calculating the angle between them in the multidimensional space defined by the spectral bands [60]. The smaller the angle the greater the similarity. The SAM algorithm is relatively insensitive to differences in brightness so that the same spectra in the shade or under direct sunlight will still have a small spectral angle and a high similarity.

- Matched Filtering (MF): Matched filtering is a technique of applying a finite-impulse response filter to an unknown spectrum to try to detect the presence of a target in the presence of noise. The matched filter is the optimal linear filter for maximizing the signal to noise ratio in the presence of additive stochastic noise. Matched filters were invented by North in 1943 to detect radar signals in the presence of white noise, but since then, have been used as a signal detection technique in many areas like hyperspectral remote sensing. Matched filters have been also used for plant species detection.

- Constrained Energy Minimization (CEM): CEM was first proposed by Harsanyi in 1993 [61] and published in 1994 [62]. CEM requires the knowledge of the spectrum target that needs to be identified and uses a finite-impulse response (FIR) filter to pass through the desired target while minimizing its output energy resulting from a background other than the desired target [53]. A correlation or covariance matrix is used to characterize the composite unknown background. CEM is similar to MF in that the only required knowledge is the target spectrum to be detected. In a mathematical sense, MF is a mean-centered version of CEM, where the data mean is subtracted from all pixel vectors [39].

- Adaptive Coherence Estimator (ACE): ACE is derived from the Generalized Likelihood Ratio (GLR) approach [63]. The ACE is invariant to relative scaling of target spectrum and has a Constant False Alarm Rate with respect to such scaling. Similar to CEM and MF, ACE does not require knowledge of all the endmembers within an image scene [39].

- Orthogonal Subspace Projection (OSP): The OSP approach was first proposed by Harsanyi and Chang [64]. They assumed that if there was a target spectrum among undesired targets, all undesired targets could be considered as interferers. In this case, an unconstrained orthogonal subspace projection eliminated the interfering effects caused by the undesired targets before the detection took place. As a consequence of annihilation of undesired targets the detectability of the desired target spectrum was improved [53]. In ENVI, an orthogonal space projection is defined to eliminate the effect of undesired targets and then a MF is applied to detect the desired target [39]. Therefore, at least one undesired target spectrum (or background spectrum in our terminology) has to be provided apart of the desired target spectrum.

- Target-Constrained Interference-Minimized Filter (TCIMF): The TCIMF assumes that a hyperspectral image scene is made of three separate signal sources: desired targets, undesired targets and interference [53]. The CEM filter takes care of the interference problem. The OSP filter takes care of the undesired target problem. The TCIMF algorithm resolves both problems simultaneously: constrains the desired and undesired spectra in such a way that the desired target spectrum can be detected while suppressing the interference [53]. The procedure is implemented in ENVI and at least one desired spectrum and one undesired spectrum (or background spectrum) have to be provided [39].

3.4. Ground Truth Data, Model Training and Model Validation

3.5. Model Training

3.6. Model Validation

3.7. Model Evaluation at a Different Area

3.8. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Prediction of S. densiflora Distribution

4.2. Model Validation

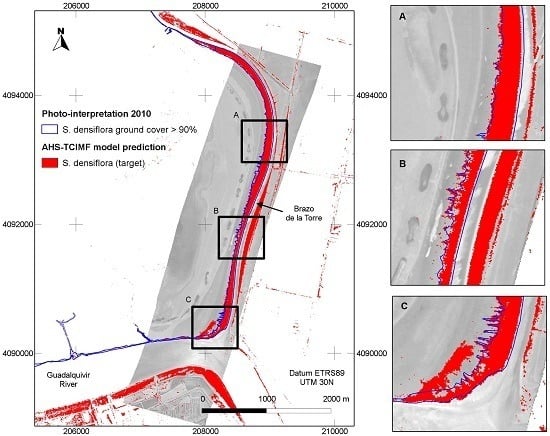

4.3. Model Evaluation at a Different Area

4.4. Statistical Analyses of Detection Performance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bortolus, A. The austral cordgrass Spartina densiflora Brong.: Its taxonomy, biogeography and natural history. J. Biogeogr. 2005, 33, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.M.; Fernández-Baco, L.; Castellanos, E.M.; Luque, C.J.; Figueroa, M.E.; Davy, A.J. Lower limits of Spartina densiflora and S. maritima in a Mediterranean salt marsh determined by different ecophysiological tolerances. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, M.E.; Castellanos, E.M. Vertical structure of Spartina maritima and Spartina densiflora in Mediterranean marshes. In Plant Form and Vegetation Structure; Werger, M.J.A., van der Aart, P.J., During, H.J., Verhoeven, J.T.A., Eds.; SPB Academic Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1988; pp. 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto, A.R.; Costa, C.S.B. Produção primária líquida aérea de Spartina densiflora Brong. (Poaceae) no estuário da laguna dos Patos, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Iheringia Sér. Bot. 2004, 59, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- González Trilla, G.; De Marco, S.; Marcovecchio, J.; Vicari, R.; Kandus, P. Net primary productivity of Spartina densiflora brong in an SW Atlantic Coastal salt marsh. Estuar. Coast. 2010, 33, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego Fernández, J.B.; García Novo, F. High-intensity versus low-intensity restoration alternatives of a tidal marsh in Guadalquivir estuary, SW Spain. Ecol. Eng. 2007, 30, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. How much information on population biology is needed to manage introduced species? Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejmánek, M.; Pitcairn, M.J. When is eradication of exotic pest plants a realistic goal. In Turning the Tide: the Eradication of Invasive Species: Proceedings of the International Conference on Eradication of Island Invasives; Veitch, C.R., Clout, M.N., Eds.; IUCN: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Naranjo, E.; Redondo-Gómez, S.; Luque, C.J.; Castellanos, E.M.; Davy, A.J.; Figueroa, M.E. Environmental limitations on recruitment from seed in invasive Spartina densiflora on a southern European salt marsh. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 79, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestir, E.L.; Khanna, S.; Andrew, M.E.; Santos, M.J.; Viers, J.H.; Greenberg, J.A.; Rajapakse, S.S.; Ustin, S.L. Identification of invasive vegetation using hyperspectral remote sensing in the California Delta ecosystem. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 4034–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.S.; Rocchini, D.; Neteler, M.; Nagendra, H. Benefits of hyperspectral remote sensing for tracking plant invasions. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, C.; de Leeuw, J.; van Duren, I.C. Remote sensing and GIS applications for mapping and spatial modelling of invasive species. In Proceedings of the ISPRS Congress, Istanbul, Turkey, 12–23 July 2004.

- Cochrane, M.A. Using vegetation reflectance variability for species level classification of hyperspectral data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2000, 21, 2075–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, P.H.; Stohlgren, T.J.; Morisette, J.T.; Kumar, S. Mapping invasive Tamarisk (Tamarix): A comparison of single-scene and time-series analyses of remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 2009, 1, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Benz, D.; Hay, S.I.; Purse, B.V.; Tatem, A.J.; Wint, G.R.W.; Rogers, D.J. Global data for ecology and epidemiology: A novel algorithm for temporal Fourier processing MODIS data. PLoS ONE 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Delgado, R.; Aragonés, D.; Ameztoy, I.; Bustamante, J. Monitoring marsh dynamics through remote sensing. In Conservation Monitoring in Freshwater Habitats; Hurford, C., Scheneider, M., Cowx, I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Asner, G.P.; Jones, M.O.; Martin, R.E.; Knapp, D.E.; Hughes, R.F. Remote sensing of native and invasive species in Hawaiian forests. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 1912–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laba, M.; Blair, B.; Downs, R.; Monger, B.; Philpot, W.; Smith, S.; Sullivan, P.; Baveye, P.C. Use of textural measurements to map invasive wetland plants in the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve with IKONOS satellite imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker Williams, A.; Hunt, E.R. Estimation of leafy spurge cover from hyperspectral imagery using mixture tuned matched filtering. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 82, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A.; Madden, M.; Welch, R. Hyperspectral image data for mapping wetland vegetation. Wetlands 2003, 23, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, L.; Thill, D.; Shafii, B.; Prather, T. Detecting spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa) with hyperspectral remote sensing technology. Weed Technol. 2002, 16, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.L.; Wood, S.D.; Sheley, R.L. Mapping invasive plants using hyperspectral imagery and Breiman Cutler classifications (randomForest). Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 100, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Stow, D.A.; Coulter, L.L.; Jafolla, J.C.; Hendricks, L.W. Detecting Tamarisk species (Tamarix spp.) in riparian habitats of Southern California using high spatial resolution hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 109, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, C.; Steinberg, S.; Shaughnessy, F.; Crawford, G. Mapping salt marsh vegetation using aerial hyperspectral imagery and linear unmixing in Humboldt Bay, California. Wetlands 2007, 27, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengra, B.W.; Johnston, C.A.; Loveland, T.R. Mapping an invasive plant, Phragmites australis, in coastal wetlands using the EO-1 Hyperion hyperspectral sensor. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 108, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M.E.; Ustin, S.L. The role of environmental context in mapping invasive plants with hyperspectral image data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 4301–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A.; Lucas, K.L.; Blossom, G.A.; Lassitter, C.L.; Holiday, D.M.; Mooneyhan, D.S.; Fastring, D.R.; Holcombe, T.R.; Griffith, J.A. Remote sensing and mapping of Tamarisk along the Colorado River, USA: A comparative use of summer-acquired Hyperion, Thematic Mapper and QuickBird data. Remote Sens. 2009, 1, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.J.; Glenn, N.F. Subpixel abundance estimates in mixture-tuned matched filtering classifications of leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.). Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 6099–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuro, M.; Chisholm, L. Assessment of Hyperion for characterizing mangrove communities. In Proceedings of the 12th JPL AVIRIS Airborne Earth Science Workshop, Pasadena, CA, USA, 31 March 2003.

- Ozesmi, S.L.; Bauer, M.E. Satellite remote sensing of wetlands. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 10, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Gong, P.; Swope, S.; Pu, R.; Carruthers, R.; Anderson, G.L.; Heaton, J.S.; Tracy, C.R. Estimation of yellow starthistle abundance through CASI-2 hyperspectral imagery using linear spectral mixture models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 101, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, R.; Zarco-Tejada, P.; Pinilla, C. Identification, Classification, and Mapping of Invasive Leafy Spurge using Hyperion, AVIRIS, and CASI; Earth Observing-1 Preliminary Technology and Science Validation Report, Part 3. Available online: https://eo1.gsfc.nasa.gov/new/validationReport/Technology/Documents/Tech.Val.Report/Science_Summary_Root.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2016).

- Pu, R.; Gong, P.; Tian, Y.; Miao, X.; Carruthers, R.I.; Anderson, G.L. Invasive species change detection using artificial neural networks and CASI hyperspectral imagery. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 140, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.L.; Carruthers, R.I.; Ge, S.; Gong, P. Monitoring of invasive Tamarix distribution and effects of biological control with airborne hyperspectral remote sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 2487–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, E.C.; Mulitsch, M.J.; Greenberg, J.A.; Whiting, M.L.; Ustin, S.L.; Kefauver, S.C. Mapping invasive aquatic vegetation in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta using hyperspectral imagery. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2006, 121, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass, L.W.; Prather, T.S.; Glenn, N.F.; Weber, K.T.; Mundt, J.T.; Pettingill, J. A review of remote sensing of invasive weeds and example of the early detection of spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa) and babysbreath (Gypsophila paniculata) with a hyperspectral sensor. Weed Sci. 2005, 53, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theriault, C.; Scheibling, R.; Hatcher, B.; Jones, W. Mapping the distribution of an invasive marine alga (Codium fragile spp. tomentosoides) in optically shallow coastal waters using the compact airborne spectrographic imager (CASI). Can. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 32, 315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Michavilla, M. Cartografía de especies de matorral de la Reserva Biológica de Doñana mediante el sistema hyperespectral aeroportado INTA-AHS. Implicaciones en el estudio y seguimiento del matorral de Doñana. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Exelis Visual Information Solutions. ENVI User’s Guide: ENVI Version 4.6.1, Exelis Visual Information Solutions: Boulder, CO, USA, 2010.

- Espinar, J.L.; García, L.V.; Clemente, L. Seed storage conditions change the germination pattern of clonal growth plants in Mediterranean salt marshes. Am. J. Bot. 2005, 92, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Murillo, P.; Fernández Zamudio, R.; Cirujano, S.; Sousa, A. Aquatic macrophytes in Donana protected area (SW Spain): An overview. Limnetica 2006, 25, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Costa Talens, M.; Castroviejo, S.; Valdés, E. Vegetación de Doñana (Huelva, España). Lazaroa 1980, 2, 5–189. [Google Scholar]

- Rejas, J.G.; Prado, E.; Jiménez, M.; Fernández-Renau, A.; Gómez, J.A.; de Miguel, E. Caracterización del sensor Hiperespectral AHS para la georreferenciación directa de imágenes a partir de un sistema inercial GPS/IMU. In Proceedings of the 6a Semana de Geomática, Barcelona, Spain, 8–13 August 2005.

- Solís, R.; Aragonés, D.; Bustamante, J. Evaluación de la precisión de georeferenciación de imágenes aeroportadas del sensor hiperespectral AHS sobre Doñana. In Teledetección: Agua y desarrollo sostenible. XIII Congreso de la Asociación Española de Teledetección; Montesinos, S., Fernández, L., Eds.; Geosys: Calatayud, Spain, 2009; pp. 437–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, L.S.; Adler-Golden, S.M.; Sundberg, R.L.; Levine, R.Y.; Perkins, T.C.; Berk, A.; Ratkowski, A.J.; Felde, G.; Hoke, M.L. Validation of the QUick atmospheric correction (QUAC) algorithm for VNIR-SWIR multi- and hyperspectral imagery. Proc. SPIE 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.S.; Adler-Golden, S.M.; Sundberg, R.L.; Ratkowski, A.J. Improved reflectance retrieval from hyper and multispectral imagery without prior scene or sensor information. Proc. SPIE 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, M.W.; Adler-Golden, S.M.; Berk, A.; Richtsmeier, S.C.; Levine, R.Y.; Bernstein, L.S.; Acharya, P.K.; Anderson, G.P.; Felde, G.W.; Hoke, M.L.; et al. Status of atmospheric correction using a MODTRAN4-based algorithm. Proc. SPIE 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.M.; Milton, E.J. The use of the empirical line method to calibrate remotely sensed data to reflectance. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1999, 20, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Renau, A.; Gómez, J.A.; de Miguel, E. The INTA AHS system. Proc. SPIE 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.J.; Johnson, B.R.; Hackwell, J.A. An in-scene method for atmospheric compensation of thermal hyperspectral data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.A.; Berman, M.; Switzer, P.; Craig, M.D. A transformation for ordering multispectral data in terms of image quality with implications for noise removal. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1988, 26, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngentob, K.N.; Roberts, D.A.; Held, A.A.; Dennison, P.E.; Jia, X.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Mapping two Eucalyptus subgenera using multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis and continuum-removed imaging spectrometry data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.I. Hyperspectral Imaging: Techniques for Spectral Detection and Classification; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marcum, J.I. A Statistical Theory of Target Detection by Pulsed Radar; U.S. Force Project Rand Research Memorandum: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Kacur, J.; Rozinaj, G.; Herrera-Garcia, S. Speech signal detection in a noisy environment using neural networks and cepstral matrices. J. Electr. Eng. 2004, 55, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.; Phinn, S. Hyperspectral data for mangrove species mapping: A comparison of pixel-based and object-based approach. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 2222–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, G.; Sanchez-Carnero, N.; Dominguez-Gomez, J.A.; Kutser, T.; Freire, J. Assessment of AHS (Airborne Hyperspectral Scanner) sensor to map macroalgal communities on the Ria de vigo and Ria de Aldan coast (NW Spain). Mar. Biol. 2012, 159, 1997–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddenbaum, H.; Schlerf, M.; Hill, J. Classification of coniferous tree species and age classes using hyperspectral data and geostatistical methods. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 5453–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertels, L.; Deronde, B.; Kempeneers, S.; Tortelboom, E. Potentials of airborne hyperspectral remote sensing for vegetation mapping of spatially heterogeneous dynamic dunes, a case study along the Belgian coastline. In Proceedings of the Dunes and Estuaries 2005: International Conference on Nature Restoration Practices in European Coastal Habitats, Koksijde, Belgium, 19–23 September 2005.

- Yuhas, R.H.; Goetz, A.F.H.; Boardman, J.W. Discrimination among semi-arid landscape endmembers using the spectral angle mapper (SAM) algorithm. In Proceedings of the Summaries of the Third Annual JPL Airborne Geoscience Workshop, Pasadena, CA, USA, 1–5 June 1992.

- Harsanyi, J.C. Detection and Classification of Subpixel Spectral Signatures in Hyperspectral Image Sequences. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanyi, J.C.; Farrand, W.H.; Chang, C.I. Detection and classification of subpixel signatures in hyperspectral image sequences. In Proceedings of the 1994 ASPRS Annual Conference, Reno, NV, USA, 25–28 April 1994; pp. 236–247.

- Kraut, S.; Scharf, L.L.; Butler, R.W. The adaptive coherence estimator: A uniformly most-powerful-invariant adaptive detection statistic. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2005, 53, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanyi, J.C.; Chang, C.I. Hyperspectral image classification and dimensionality reduction: An orthogonal subspace projection approach. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1994, 32, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, C.E.; Strahler, A.H. The factor of scale in remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 1987, 21, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belluco, E.; Camuffo, M.; Ferrari, S.; Modenese, L.; Silvestri, S.; Marani, A.; Marani, M. Mapping salt-marsh vegetation by multispectral and hyperspectral remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 105, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Flight altitude | 1844 m (asl) |

| Terrain altitude | 0–10 m (asl) |

| Date | 21 May 2011 |

| Time (UTC) | 12:29 |

| Time (local) | 14:29 |

| Flight course | 169° |

| Flight-line ID | 20110521D-18.7-P25 |

| length/duration | 13.5 km/187 s |

| Sensor | CASI | AHS |

|---|---|---|

| FOV | 0.698 rad (40°) | 1.571 rad (90°) |

| IFOV | 0.49 mrad | 2.5 mrad |

| Pixels per line | 1441 | 750 |

| Swath | 1635 m | 3678 m |

| GSD, pixel size | ~1 m | ~4 m |

| VNIR range | 360–1052 nm | 430–1000 nm |

| (No. bands) | (144) | (20) |

| VNIR FWH | 2.75 nm | 27–30 nm |

| SWIR range | - | 1600 nm |

| (No. bands) | (1) | |

| SWIR FWHM | - | 85 nm |

| MIR range | - | 2000–2500 nm |

| (No. bands) | (42) | |

| MIR FWHM | - | 14–18 nm |

| TIR range | - | 3000–13,000 nm |

| (No. bands) | (17) | |

| TIR FWHM | - | 288–556 nm |

| AHS scan frequency | - | 18.7 rps |

| analog to digital conversion | 14 bit | 12 bit |

| Class | Cover Type | GPS | Photo-Interpreted | Total | Training Set | Testing Set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | S. densiflora > 80% cover | 7 | 8 | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| B | Arthrocnemum ~50% cover | 2 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Sarcocornia ~50%–80% cover | 7 | 33 | 40 | 20 | 20 | |

| Wet bare soil | 0 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Dry bare soil | 0 | 36 | 36 | 18 | 18 | |

| Water | 0 | 36 | 36 | 18 | 18 | |

| Total | 16 | 135 | 151 | 74 | 77 |

| Hyperspectral Image (1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm (2) | CASI (3) | CASI-4m | CASI-4m-SR | AHS | AHS-4m-SR |

| SAM | 84.49 | 80.11 | 84.57 | 80.47 | 82.64 |

| MF | 92.65 | 77.23 | 97.28 | 84.35 | 91.19 |

| CEM | 93.34 | 77.89 | 97.70 | 84.36 | 91.84 |

| ACE | 111.58 | 115.72 | 85.67 | 54.22 | 75.40 |

| OSP | 92.15 | 88.39 | 90.18 | 87.88 | 88.56 |

| TCIMF | 94.01 | 79.61 | 99.01 | 83.55 | 92.15 |

| Sensor (1) | Algorithm (2) | OE (%) (3) | CE (%) | CCR (%) | K | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASI | SAM | 13.35 | 0 | 95.03 | 0.8907 | 0.9986 |

| MF | 0.24 | 0.72 | 99.64 | 0.9923 | 0.9999 | |

| CEM | 0.19 | 0.87 | 99.60 | 0.9915 | 0.9999 | |

| ACE | 0.05 | 5.26 | 97.91 | 0.9559 | 0.9999 | |

| OSP | 2.64 | 0 | 99.02 | 0.9789 | 0.9986 | |

| TCIMF | 0.21 | 0.61 | 99.69 | 0.9935 | 0.9999 | |

| CASI-4m | SAM | 20.45 | 0 | 92.57 | 0.8320 | 0.9989 |

| MF | 2.74 | 2.74 | 98.00 | 0.9569 | 0.9989 | |

| CEM | 2.74 | 2.74 | 98.00 | 0.9569 | 0.9989 | |

| ACE | 0.17 | 11.82 | 95.07 | 0.8964 | 0.9980 | |

| OSP | 2.92 | 0 | 98.94 | 0.9769 | 0.9991 | |

| TCIMF | 2.06 | 2.39 | 98.38 | 0.9650 | 0.9992 | |

| CASI-4m-SR | SAM | 18.18 | 0 | 93.38 | 0.8513 | 0.9989 |

| MF | 0 | 0.29 | 9981 | 0.9960 | 1 | |

| CEM | 0 | 0.29 | 99.81 | 0.9960 | 1 | |

| ACE | 0.17 | 0 | 99.94 | 0.9987 | 1 | |

| OSP | 2.74 | 0 | 99.00 | 0.9783 | 0.9994 | |

| TCIMF | 0 | 0.29 | 99.81 | 0.9960 | 1 | |

| AHS | SAM | 13.19 | 0 | 93.04 | 0.8429 | 0.9999 |

| MF | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| CEM | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| ACE | 4.40 | 0 | 98.40 | 0.9651 | 1 | |

| OSP | 2.11 | 0 | 99.23 | 0.9833 | 0.9999 | |

| TCIMF | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| AHS-4m-SR | SAM | 19.04 | 0 | 93.07 | 0.8440 | 0.9996 |

| MF | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| CEM | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 1 | |

| ACE | 0.17 | 0 | 99.94 | 0.9987 | 1 | |

| OSP | 2.92 | 0 | 98.94 | 0.9769 | 1 | |

| TCIMF | 0 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 1 |

| Estimate (2) | Std. Error | t-Value | P (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (1) | 0.728 | 0.019 | ||

| sensor (CASI) | −0.055 | 0.009 | −5.804 | <0.0001 |

| spatial resolution (4M) | −0.046 | 0.013 | −3.672 | 0.0006 |

| spectral resolution (SR) | 0.041 | 0.009 | 4.357 | <0.0001 |

| atm. correction (RAW) | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.945 | ns |

| algorithm (CEM) (4) | −0.005 | 0.021 | −0.253 | ns |

| algorithm (MF) | −0.005 | 0.021 | −0.253 | ns |

| algorithm (OSP) | −0.069 | 0.021 | −3.326 | 0.0018 |

| algorithm (SAM) | 0.031 | 0.021 | 1.481 | ns |

| algorithm (TCIMF) | −0.041 | 0.021 | −1.990 | 0.052 |

| atm. correction (RAW): Algorithm (CEM) | −0.043 | 0.029 | −1.463 | ns |

| atm. correction (RAW): Algorithm (MF) | −0.038 | 0.029 | −1.303 | ns |

| atm. correction (RAW): Algorithm (OSP) | −0.115 | 0.029 | −3.906 | 0.0003 |

| atm. correction (RAW): Algorithm (SAM) | −0.108 | 0.029 | −3.693 | 0.0006 |

| atm. correction (RAW): Algorithm (TCIMF) | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.050 | ns |

| Null deviance: 0.2492, 59 df | ||||

| Residual deviance: 0.0484 on 45 df | ||||

| AIC: −225.03 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustamante, J.; Aragonés, D.; Afán, I.; Luque, C.J.; Pérez-Vázquez, A.; Castellanos, E.M.; Díaz-Delgado, R. Hyperspectral Sensors as a Management Tool to Prevent the Invasion of the Exotic Cordgrass Spartina densiflora in the Doñana Wetlands. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8121001

Bustamante J, Aragonés D, Afán I, Luque CJ, Pérez-Vázquez A, Castellanos EM, Díaz-Delgado R. Hyperspectral Sensors as a Management Tool to Prevent the Invasion of the Exotic Cordgrass Spartina densiflora in the Doñana Wetlands. Remote Sensing. 2016; 8(12):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8121001

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustamante, Javier, David Aragonés, Isabel Afán, Carlos J. Luque, Andrés Pérez-Vázquez, Eloy M. Castellanos, and Ricardo Díaz-Delgado. 2016. "Hyperspectral Sensors as a Management Tool to Prevent the Invasion of the Exotic Cordgrass Spartina densiflora in the Doñana Wetlands" Remote Sensing 8, no. 12: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8121001

APA StyleBustamante, J., Aragonés, D., Afán, I., Luque, C. J., Pérez-Vázquez, A., Castellanos, E. M., & Díaz-Delgado, R. (2016). Hyperspectral Sensors as a Management Tool to Prevent the Invasion of the Exotic Cordgrass Spartina densiflora in the Doñana Wetlands. Remote Sensing, 8(12), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8121001