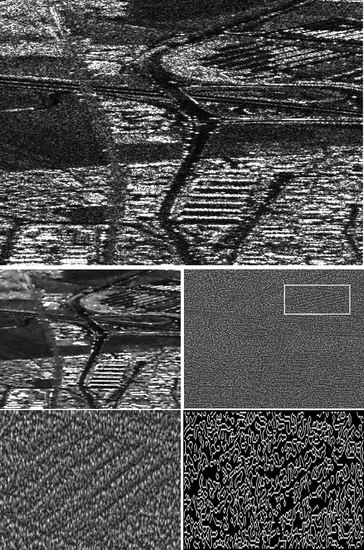

Figure 1.

(Top): original SAR image; (Middle): SRAD () filtered image and ratio image; (Bottom): zoom of a selected area within the ratio image and extracted edges by Canny’s edge detector.

Figure 1.

(Top): original SAR image; (Middle): SRAD () filtered image and ratio image; (Bottom): zoom of a selected area within the ratio image and extracted edges by Canny’s edge detector.

Figure 2.

A step: constant and textured versions, and their return. (a) Constant step and speckled return; (b) Textured step and speckled return.

Figure 2.

A step: constant and textured versions, and their return. (a) Constant step and speckled return; (b) Textured step and speckled return.

Figure 3.

Estimated speckle by the ideal filter and by overmoothing.

Figure 3.

Estimated speckle by the ideal filter and by overmoothing.

Figure 4.

Slowly varying backscatter, fully developed speckle, and estimated speckle. (a) Slowly-varying mean value and its return; (b) Estimated speckle.

Figure 4.

Slowly varying backscatter, fully developed speckle, and estimated speckle. (a) Slowly-varying mean value and its return; (b) Estimated speckle.

Figure 5.

Ratio image resulting from neglecting a slowly varying structure under fully developed speckle.

Figure 5.

Ratio image resulting from neglecting a slowly varying structure under fully developed speckle.

Figure 6.

The effect of oversmoothing on an image of strips of varying width. (a) Strips and speckle; (b) Filtered strips with oversmoothing.

Figure 6.

The effect of oversmoothing on an image of strips of varying width. (a) Strips and speckle; (b) Filtered strips with oversmoothing.

Figure 7.

Estimated speckle: ideal and oversmoothing filters.

Figure 7.

Estimated speckle: ideal and oversmoothing filters.

Figure 8.

Speckled strips, result of applying a BoxCar filter, ratio image. (a) Speckled strips; (b) Filtered strips; (c) Ratio image.

Figure 8.

Speckled strips, result of applying a BoxCar filter, ratio image. (a) Speckled strips; (b) Filtered strips; (c) Ratio image.

Figure 9.

Selection of mean and ENL values for the first-order measure.

Figure 9.

Selection of mean and ENL values for the first-order measure.

Figure 10.

Blocks and points phantom, and pixels simulated single-look intensity image. (a) Blocks and points phantom; (b) Speckled version, single look.

Figure 10.

Blocks and points phantom, and pixels simulated single-look intensity image. (a) Blocks and points phantom; (b) Speckled version, single look.

Figure 11.

Results for the simulated single-look intensity data. Top to bottom, (left) results of applying the SRAD, the E-Lee, the PPB and the FANS filters. Top to bottom (right), their ratio images.

Figure 11.

Results for the simulated single-look intensity data. Top to bottom, (left) results of applying the SRAD, the E-Lee, the PPB and the FANS filters. Top to bottom (right), their ratio images.

Figure 12.

Zoom of the results for synthetic data: (top) Noisy image, (first row, left) SRAD filter, (first row, right) E-Lee filter, (second row, left) PPB filter and, (second row, right) FANS filter.

Figure 12.

Zoom of the results for synthetic data: (top) Noisy image, (first row, left) SRAD filter, (first row, right) E-Lee filter, (second row, left) PPB filter and, (second row, right) FANS filter.

Figure 13.

Intensity AIRSAR images, HH polarization, three looks. (a) Flevoland; (b) San Francisco bay.

Figure 13.

Intensity AIRSAR images, HH polarization, three looks. (a) Flevoland; (b) San Francisco bay.

Figure 14.

Results for the Flevoland image. Top to bottom, (left) results of applying SRAD, E-Lee, PPB and FANS filters. Top to bottom (right), their ratio images.

Figure 14.

Results for the Flevoland image. Top to bottom, (left) results of applying SRAD, E-Lee, PPB and FANS filters. Top to bottom (right), their ratio images.

Figure 15.

Zoom of the results for Flevoland image: (top) Noisy image, (first row, left) SRAD filter, (first row, right) E-Lee filter, (second row, left) PPB filter and, (second row, right) FANS filter.

Figure 15.

Zoom of the results for Flevoland image: (top) Noisy image, (first row, left) SRAD filter, (first row, right) E-Lee filter, (second row, left) PPB filter and, (second row, right) FANS filter.

Figure 16.

Result for the San Francisco bay image. Top to bottom, (left) results of applying SRAD, E-Lee, PPB and FANS. Top to bottom (right), their ratio images.

Figure 16.

Result for the San Francisco bay image. Top to bottom, (left) results of applying SRAD, E-Lee, PPB and FANS. Top to bottom (right), their ratio images.

Figure 17.

Zoom of the results for San Francisco image: (top) Noisy image, (first row, left) SRAD filter, (first row, right) E-Lee filter, (second row, left) PPB filter and, (second row, right) FANS filter.

Figure 17.

Zoom of the results for San Francisco image: (top) Noisy image, (first row, left) SRAD filter, (first row, right) E-Lee filter, (second row, left) PPB filter and, (second row, right) FANS filter.

Figure 18.

Intensity Pi-SAR, HH one look Niigata image (left); Results of applying FANS filters with default parameters (middle) and with optimized parameters (right).

Figure 18.

Intensity Pi-SAR, HH one look Niigata image (left); Results of applying FANS filters with default parameters (middle) and with optimized parameters (right).

Figure 19.

Ratio images for Niigata data; FANS with default parameters (left) and with optimized parameters (right).

Figure 19.

Ratio images for Niigata data; FANS with default parameters (left) and with optimized parameters (right).

Table 1.

Quantitative evaluation of filters on the simulated SAR image (best values in boldface).

Table 1.

Quantitative evaluation of filters on the simulated SAR image (best values in boldface).

| Simulated SAR Data | True | Simulated | SRAD | E-Lee | PPB | FANS |

|---|

| Background | | 10 | 9.93 | 9.94 | 9.91 | 10.12 | 10.13 |

| s | 10 | 9.99 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 0.45 |

| ENL | 1 | 0.98 | 105.86 | 115.13 | 90.87 | 489.38 |

| Top left square | | 2 | 1.96 | 1.97 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 2.01 |

| s | 2 | 1.93 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| ENL | 1 | 1.03 | 101.80 | 106.17 | 94.64 | 640.55 |

| Top right square | | 40 | 40.07 | 39.98 | 39.85 | 40.69 | 40.59 |

| s | 40 | 39.83 | 4.41 | 4.24 | 3.89 | 2.04 |

| ENL | 1 | 1.01 | 82.09 | 88.10 | 109.20 | 394.84 |

| Bottom left square | | 60 | 59.92 | 60.12 | 59.93 | 60.17 | 61.54 |

| s | 60 | 60.00 | 6.76 | 5.78 | 5.67 | 2.88 |

| ENL | 1 | 0.99 | 78.88 | 107.49 | 112.50 | 455.83 |

| Bottom right square | | 80 | 79.32 | 79.35 | 78.99 | 81.53 | 81.61 |

| s | 80 | 78.89 | 8.76 | 7.63 | 8.20 | 3.68 |

| ENL | 1 | 1.01 | 81.88 | 106.99 | 96.68 | 490.45 |

| Whole image | PSNR | — | 73.87 | 80.30 | 78.72 | 79.07 | 77.85 |

| MSSIM | — | 0.38 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| — | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| Ratio image | | 1 | — | 1.0744 | 1.0346 | 1.0858 | 1.0028 |

| 1 | — | 0.9914 | 1.0019 | 0.9775 | 0.9974 |

Table 2.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for the simulated data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

Table 2.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for the simulated data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

| Filter | | | | | |

|---|

| SRAD | 0.3026 | 0.3023 | 9.41 | 4.6634 | 7.0371 |

| E-Lee | 0.3465 | 0.3460 | 14.30 | 2.8781 | 8.5910 |

| PPB | 0.5551 | 0.5543 | 14.56 | 5.7751 | 10.1704 |

| FANS | 0.3827 | 0.3829 | 6.26 | 2.0944 | 4.1816 |

Table 3.

Quantitative assessment of Flevoland filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

Table 3.

Quantitative assessment of Flevoland filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

| Filter | ROI-1 | ROI-2 |

|---|

| s | ENL | | s | ENL |

|---|

| Original | 0.0047 | 0.0030 | 2.5000 | 0.0208 | 0.0110 | 3.5441 |

| SRAD | 0.0047 | 7.3561 | 41.2367 | 0.0204 | 0.0012 | 283.7539 |

| E-Lee | 0.0047 | 7.4516 | 39.1870 | 0.0206 | 0.0012 | 276.1669 |

| PPB | 0.0048 | 3.3690 | 200.6540 | 0.0212 | 5.8933 | 1.2918 |

| FANS | 0.0047 | 5.0309 | 86.1449 | 0.0209 | 6.2295 | 1.1290 |

Table 4.

Quantitative assessment of ratio images for Flevoland filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

Table 4.

Quantitative assessment of ratio images for Flevoland filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

| Filter | ROI-1 | ROI-2 |

|---|

| ENL | | ENL |

|---|

| SRAD | 0.9862 | 2.9836 | 1.0152 | 3.6287 |

| E-Lee | 0.9981 | 2.9824 | 1.0097 | 3.5755 |

| PPB | 0.9720 | 2.8048 | 0.9729 | 3.8159 |

| FANS | 0.9942 | 2.8822 | 0.9874 | 3.7082 |

Table 5.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for Flevoland data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

Table 5.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for Flevoland data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

| Filter | | | | | |

|---|

| SRAD | 0.2043 | 0.2029 | 66.81 | 8.2782 | 37.5450 |

| E-Lee | 0.2247 | 0.2212 | 161.30 | 11.2636 | 86.2818 |

| PPB | 0.6210 | 0.6140 | 114.30 | 10.2211 | 5.6174 |

| FANS | 0.8944 | 0.8943 | 1.09 | 8.8547 | 4.9771 |

Table 6.

Quantitative assessment of San Francisco bay filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

Table 6.

Quantitative assessment of San Francisco bay filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

| Filter | ROI-1 | ROI-2 |

|---|

| s | ENL | | s | ENL |

|---|

| Original | 6.8327 | 3.8422 | 3.1625 | 0.0018 | 8.9834 | 4.1959 |

| SRAD | 7.0597 | 3.6942 | 365.2071 | 0.0021 | 8.1671 | 674.1768 |

| E-Lee | 6.8252 | 8.9163 | 58.5959 | 0.0020 | 1.7975 | 129.6569 |

| PPB | 6.9884 | 3.2459 | 463.5443 | 0.0020 | 1.5831 | 163.9516 |

| FANS | 6.9156 | 4.7095 | 215.6278 | 0.0020 | 3.5513 | 3.2947 |

Table 7.

Quantitative assessment of ratio images for San Francisco bay filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

Table 7.

Quantitative assessment of ratio images for San Francisco bay filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

| Filter | ROI-1 | ROI-2 |

|---|

| ENL | | ENL |

|---|

| SRAD | 0.9651 | 3.3477 | 0.8634 | 4.7106 |

| E-Lee | 0.9955 | 3.5834 | 0.8948 | 4.9673 |

| PPB | 0.9692 | 3.4437 | 0.9004 | 4.7289 |

| FANS | 0.9829 | 3.3819 | 0.9023 | 4.2443 |

Table 8.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for San Francisco bay data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

Table 8.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for San Francisco bay data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

| Filter | | | | | |

|---|

| SRAD | 0.5643 | 0.5368 | 487.26 | 0.2216 | 5.0942 |

| E-Lee | 0.5813 | 0.5586 | 390.35 | 0.3262 | 4.2297 |

| PPB | 0.7449 | 0.7419 | 40.65 | 0.5395 | 0.9460 |

| FANS | 0.7138 | 0.7141 | 5.10 | 0.4231 | 0.4741 |

Table 9.

Quantitative assessment of San Francisco bay filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

Table 9.

Quantitative assessment of San Francisco bay filtered data in selected ROIs (best values in boldface).

| Filter | | s | ENL |

|---|

| Original | 0.0283 | 0.0261 | 1.1757 |

| FANS (default parameters) | 0.0302 | 0.0106 | 8.1171 |

| FANS (optimized parameters) | 0.0295 | 0.0083 | 12.6325 |

Table 10.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for Niigata data (best values in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

Table 10.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for Niigata data (best values in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

| Filter | | ENL |

|---|

| FANS (default parameters) | 0.8627 | 2.2270 |

| FANS (optimized parameters) | 0.9006 | 1.8745 |

Table 11.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for Niigata data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

Table 11.

Quantitative evaluation of ratio images for Niigata data (best value in boldface), computed on automatically detected homogeneous areas.

| Filter | | | |

|---|

| FANS (default parameters) | 0.4833 | 20.89 | 10.6867 |

| FANS (optimized parameters) | 0.3794 | 6.50 | 3.4397 |