Patulin in Apples and Apple-Based Food Products: The Burdens and the Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Burdens of Patulin Accumulation in Apples and Apple Products

2.1. Factors Affecting Patulin Production in Apples

2.1.1. Toxigenic Penicillium Species

2.1.2. Traits of Apple Fruits

2.1.3. Environmental Conditions

2.2. Challenges in the Control of Patulin Levels in Apple Products

2.2.1. Difficulties of Patulin Detection in Apple Products

2.2.2. Insufficient Toxicological Assessments of Patulin and Its Breakdown Products

2.2.3. Unspecific Mechanisms of Patulin Degradation by Microorganisms

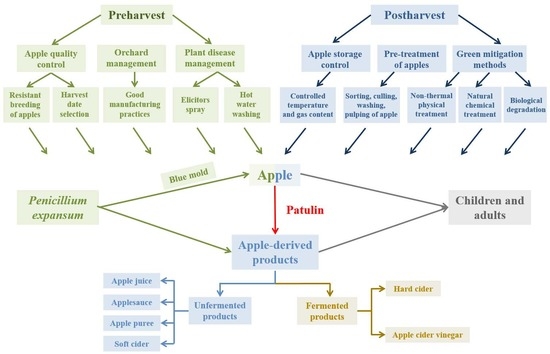

3. Strategies for the Mitigation of Patulin Contamination in Fresh Apples and Processed Products

3.1. Preharvest Control of Blue Mold to Reduce Patulin Accumulation in Apples

3.1.1. Selection of Blue Mold Resistant Apple Cultivars

3.1.2. Good Management Practices in Apple Orchards

3.1.3. Preharvest Application of Plant Elicitors

3.2. Postharvest Control of Patulin Contamination in Apples and Apple-Products

3.2.1. Control of Patulin Production during Apple Storage

3.2.2. Mitigation of Patulin Contamination during Apple Processing

3.2.3. Reduction of Patulin Contamination from Apple Products

4. Conclusions and Future Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Le Gall, S.; Even, S.; Lahaye, M. Fast estimation of dietary fiber content in apple. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 1401–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinowska, M.; Bielawska, A.; Lewandowska-Siwkiewicz, H.; Priebe, W.; Lewandowski, W. Apples: Content of phenolic compounds vs. variety, part of apple and cultivation model, extraction of phenolic compounds, biological properties. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 84, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. FAO Statistical Database; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, C.A. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruit. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 133, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moake, M.M.; Padilla Zakour, O.I.; Worobo, R.W. Comprehensive review of patulin control methods in foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2005, 4, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JECFA. 44th Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Commission Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 Setting Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Foodstuffs; Official Journal of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2006; Volume L364, pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- US-FDA. CPG Sec. 510.150 Apple Juice, Apple Juice Concentrates, and Apple Juice Products–Adulteration with Patulin; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2005.

- Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. GB 2761-2011 of 20 April 2011 China National Food Safety Standard: Maximum Limit of Mycotoxins in Food; Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Health Canada. Summary of Comments from Health Canada’s Consultation on Its Proposal to Introduce a Maximum Level for the Presence of Patulin in Apple Juice and Unfermented Apple Cider Sold in Canada; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2012.

- USDA. Fresh Apples, Graps, and Pears: World Markets and Trade; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Yuan, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J. Patulin content in apple products marketed in Northeast China. Food Control 2010, 21, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T. Survey of patulin in apple juice concentrates in Shaanxi (China) and its dietary intake. Food Control 2013, 34, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Szteke, B.; Goszcz, H. Patulin content in Polish apple juices. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2004, 55, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, D.; Ciavorella, A.; Frati, S.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M. Incidence and level of patulin contamination in pure and mixed apple juices marketed in Italy. Food Control 2007, 18, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.L.; Bobe, G.; Bourquin, L.D. Patulin surveillance in apple cider and juice marketed in Michigan. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, S.Z.; Malik, S.; Asi, M.R.; Selamat, J.; Malik, N. Natural occurrence of patulin in different fruits, juices and smoothies and evaluation of dietary intake in Punjab, Pakistan. Food Control 2018, 84, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, R.; Yang, H.; Qi, P.; Xiao, Y.; Qian, M. Occurrence of patulin in various fruit products and dietary exposure assessment for consumers in China. Food Control 2017, 78, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, M.J.; Alvito, P.C.; Almeida, C.M. Occurrence of patulin in apple-based-foods in Portugal. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Arbizu, M.; Amézqueta, S.; González-Peñas, E.; de Cerain, A.L. Occurrence of patulin and its dietary intake through apple juice consumption by the Spanish population. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqué, E.; Vargas-Murga, L.; Gómez-Catalán, J.; de Lapuente, J.; Llobet, J.M. Occurrence of patulin in organic and conventional apple-based food marketed in Catalonia and exposure assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torović, L.; Dimitrov, N.; Lopes, A.; Martins, C.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R. Patulin in fruit juices: Occurrence, bioaccessibility, and risk assessment for Serbian population. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oteiza, J.M.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Campagnollo, F.B.; Granato, D.; Mahmoudi, M.R.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Gianuzzi, L. Influence of production on the presence of patulin and ochratoxin A in fruit juices and wines of Argentina. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 80, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaied, C.; Abid, S.; Hlel, W.; Bacha, H. Occurrence of patulin in apple-based-foods largely consumed in Tunisia. Food Control 2013, 31, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.P.; Sakai, R.; Manaf, N.A.; Rodhi, A.M.; Saad, B. High performance liquid chromatography method for the determination of patulin and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in fruit juices marketed in Malaysia. Food Control 2014, 38, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funes, G.; Resnik, S. Determination of patulin in solid and semisolid apple and pear products marketed in Argentina. Food Control 2009, 20, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonerba, E.; Conte, R.; Ceci, E.; Tantillo, G. Assessment of dietary intake of patulin from baby foods. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, T123–T125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.; Raiola, A.; Mañes, J.; Ritieni, A. Presence of mycotoxin in commercial infant formulas and baby foods from Italian market. Food Control 2014, 39, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, S.; Mateo, E.M.; Sanchis, V.; Valle-Algarra, F.M.; Ramos, A.J.; Jiménez, M. Patulin contamination in fruit derivatives, including baby food, from the Spanish market. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzani, S.; Reverberi, M.; Punelli, M.; Ippolito, A.; Fanelli, C. Study on the role of patulin on pathogenicity and virulence of Penicillium expansum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, A.; Bompeix, G. Diversity and population dynamics of Penicillium spp. on apples in pre-and postharvest environments: Consequences for decay development. Plant Pathol. 2005, 54, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, H.; Marín, S.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V. Influence of post-harvest technologies applied during cold storage of apples in Penicillium expansum growth and patulin accumulation: A review. Food Control 2010, 21, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Code of Practice for the Prevention and Reduction of Patulin Contamination in Apple Juice and Apple Juice Ingredients in Other Beverages; In CAC/RPC; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003; Volume 50, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, S.; Li, X.-Z.; Shao, S.; Behar, M.; Svircev, A.; Tsao, R.; Zhou, T. Potential mycotoxin contamination risks of apple products associated with fungal flora of apple core. Food Control 2015, 47, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant’Ana, A.S.; Simas, R.C.; Almeida, C.A.; Cabral, E.C.; Rauber, R.H.; Mallmann, C.A.; Eberlin, M.N.; Rosenthal, A.; Massaguer, P.R. Influence of package, type of apple juice and temperature on the production of patulin by Byssochlamys nivea and Byssochlamys fulva. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 142, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannous, J.; Keller, N.P.; Atoui, A.; El Khoury, A.; Lteif, R.; Oswald, I.P.; Puel, O. Secondary metabolism in Penicillium expansum: Emphasis on recent advances in patulin research. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 2082–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisvad, J. A critical review of producers of small lactone mycotoxins: Patulin, penicillic acid and moniliformin. World Mycotoxin J. 2018, 11, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, S.; Sionov, E.; Prusky, D. Role of patulin in post-harvest diseases. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2016, 30, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Sant’Ana, A.; Rosenthal, A.; de Massaguer, P.R. The fate of patulin in apple juice processing: A review. Food Res. Int. 2008, 41, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioi, J.D.; Zhou, T.; Tsao, R.; Marcone, M.F. Mitigation of patulin in fresh and processed foods and beverages. Toxins 2017, 9, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barad, S.; Espeso, E.A.; Sherman, A.; Prusky, D. Ammonia activates pacC and patulin accumulation in an acidic environment during apple colonization by Penicillium expansum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastburn, D.; McElrone, A.; Bilgin, D. Influence of atmospheric and climatic change on plant–pathogen interactions. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, H.; Sanchis, V.; Rovira, A.; Ramos, A.J.; Marín, S. Patulin accumulation in apples during postharvest: Effect of controlled atmosphere storage and fungicide treatments. Food Control 2007, 18, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, N.; Vlaemynck, G.; Van Pamel, E.; Colman, D.; Heyndrickx, M.; Van Hove, F.; De Meulenaer, B.; Devlieghere, F.; Van Coillie, E. Patulin production by Penicillium expansum isolates from apples during different steps of long-term storage. World Mycotoxin J. 2016, 9, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholberg, P.L.; Bedford, K.; Stokes, S. Sensitivity of Penicillium spp. and Botrytis cinerea to pyrimethanil and its control of blue and gray mold of stored apples. Crop Prot. 2005, 24, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, I.D.; Pizzutti, I.R.; Dias, J.V.; Fontana, M.E.; Brackmann, A.; Anese, R.O.; Thewes, F.R.; Marques, L.N.; Cardoso, C.D. Patulin accumulation in apples under dynamic controlled atmosphere storage. Food Chem. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zeebroeck, M.; Ramon, H.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Nicolaï, B.; Tijskens, E. Impact damage of apples during transport and handling. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 45, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, B.; Gaiaschi, A.; Galli, C.L.; Restani, P. Patulin in apple-based foods: Occurrence and safety evaluation. Food Addit. Contam. 2000, 17, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, A.-R.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Levin, E.; Sela, N.; Selma-Lázaro, C.; Carmona, L.; Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S.; González-Candelas, L.; Gabaldón, T. Genome, transcriptome, and functional analyses of Penicillium expansum provide new insights into secondary metabolism and pathogenicity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, J.; Tsao, R.; Zhou, T. Factors affecting patulin production by Penicillium expansum. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanzani, S.; Susca, A.; Mastrorosa, S.; Solfrizzo, M. Patulin risk associated with blue mould of pome fruit marketed in southern Italy. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. 2017, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judet-Correia, D.; Bollaert, S.; Duquenne, A.; Charpentier, C.; Bensoussan, M.; Dantigny, P. Validation of a predictive model for the growth of Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum on grape berries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 142, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannous, J.; Atoui, A.; El Khoury, A.; Francis, Z.; Oswald, I.P.; Puel, O.; Lteif, R. A study on the physicochemical parameters for Penicillium expansum growth and patulin production: Effect of temperature, pH, and water activity. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, Y.; Li, B.; Tian, S. Effects of carbon, nitrogen and ambient pH on patulin production and related gene expression in Penicillium expansum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 206, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snini, S.P.; Tannous, J.; Heuillard, P.; Bailly, S.; Lippi, Y.; Zehraoui, E.; Barreau, C.; Oswald, I.P.; Puel, O. Patulin is a cultivar-dependent aggressiveness factor favouring the colonization of apples by Penicillium expansum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janisiewicz, W.J.; Saftner, R.A.; Conway, W.S.; Forsline, P.L. Preliminary evaluation of apple germplasm from Kazakhstan for resistance to postharvest blue mold in fruit caused by Penicillium expansum. HortScience 2008, 43, 420–426. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Janisiewicz, W.J.; Nichols, B.; Jurick, W.M., II; Chen, P. Composition of phenolic compounds in wild apple with multiple resistance mechanisms against postharvest blue mold decay. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 127, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, L.; Wisniewski, M.; Norelli, J.; Viñas, I.; Torres, R.; Usall, J.; Phillips, J.; Droby, S.; Teixidó, N. Transcriptomic profiling of apple in response to inoculation with a pathogen (Penicillium expansum) and a non-pathogen (Penicillium digitatum). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 32, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norelli, J.L.; Wisniewski, M.; Fazio, G.; Burchard, E.; Gutierrez, B.; Levin, E.; Droby, S. Genotyping-by-sequencing markers facilitate the identification of quantitative trait loci controlling resistance to Penicillium expansum in Malus sieversii. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, A.-R.; Norelli, J.; Burchard, E.; Abdelfattah, A.; Levin, E.; González-Candelas, L.; Droby, S.; Wisniewski, M. Transcriptomic response of resistant (PI613981–Malus sieversii) and susceptible (“Royal Gala”) genotypes of apple to blue mold (Penicillium expansum) infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janisiewicz, W.J.; Nichols, B.; Bauchan, G.; Chao, T.C.; Jurick, W.M. Wound responses of wild apples suggest multiple resistance mechanism against blue mold decay. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 117, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, J.; Ma, F.; Shi, S.; Qi, X.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, J. Changes and postharvest regulation of activity and gene expression of enzymes related to cell wall degradation in ripening apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 56, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, L.; Viñas, I.; Torres, R.; Usall, J.; Buron-Moles, G.; Teixidó, N. Increasing maturity reduces wound response and lignification processes against Penicillium expansum (pathogen) and Penicillium digitatum (non-host pathogen) infection in apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 88, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, R.A.S.; Peniche, R.Á.M.; Medrano, S.A.; Muñoz, L.S.; Ortíz, M.d.S.C.; Espasa, N.T.; Sanchis, R.T. Effect of maturity stage, ripening time, harvest year and fruit characteristics on the susceptibility to Penicillium expansum link of apple genotypes from Queretaro, Mexico. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 180, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi-Afzadi, M.; Tahir, I.; Nybom, H. Impact of harvesting time and fruit firmness on the tolerance to fungal storage diseases in an apple germplasm collection. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 82, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, S.; Morales, H.; Hasan, H.; Ramos, A.; Sanchis, V. Patulin distribution in Fuji and Golden apples contaminated with Penicillium expansum. Food Addit. Contam. 2006, 23, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurick, W.M.; Janisiewicz, W.J.; Saftner, R.A.; Vico, I.; Gaskins, V.L.; Park, E.; Forsline, P.L.; Fazio, G.; Conway, W.S. Identification of wild apple germplasm (Malus spp.) accessions with resistance to the postharvest decay pathogens Penicillium expansum and Colletotrichum acutatum. Plant Breed. 2011, 130, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.; Nybom, H.; Ahmadi-Afzadi, M.; Røen, K.; Sehic, J.; Røen, D. Susceptibility to blue mold caused by Penicillium expansum in apple cultivars adapted to a cool climate. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2015, 80, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Tu, K.; Tu, S.; Su, J.; Zhao, Y. Effects of heat treatment on wound healing in Gala and Red fuji apple fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4303–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilanova, L.; Vall-llaura, N.; Torres, R.; Usall, J.; Teixidó, N.; Larrigaudière, C.; Giné-Bordonaba, J. Penicillium expansum (compatible) and Penicillium digitatum (non-host) pathogen infection differentially alter ethylene biosynthesis in apple fruit. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 120, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi-Afzadi, M.; Nybom, H.; Ekholm, A.; Tahir, I.; Rumpunen, K. Biochemical contents of apple peel and flesh affect level of partial resistance to blue mold. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 110, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Barad, S.; Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Tannous, J.; Dubey, A.; Glam Matana, N.; Tian, S.; Li, B.; Keller, N. LaeA regulation of secondary metabolism modulates virulence in Penicillium expansum and is mediated by sucrose. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, B.; Kótai, É.; Varga, M.; Pálfi, X.; Baranyi, N.; Szigeti, G.; Kocsubé, S.; Varga, J. Climate change and mycotoxin contamination in Central Europe: An overview of recent findings. Rev. Agric. Rural Dev. 2013, 2, 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, M.C.; Bouwer, J.J. The supply value chain of fresh produce from field to home: Refrigeration and other supporting technologies. In Postharvest Handling, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 449–483. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Rudell, D.R.; Davies, P.J.; Watkins, C.B. Metabolic changes in 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP)-treated ‘Empire’apple fruit during storage. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougouli, M.; Koutsoumanis, K.P. Modelling growth of Penicillium expansum and Aspergillus niger at constant and fluctuating temperature conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 140, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prata, M.B.; Mussatto, S.I.; Rodrigues, L.R.; Teixeira, J.A. Fructooligosaccharide production by Penicillium expansum. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morales, H.; Marín, S.; Rovira, A.; Ramos, A.; Sanchis, V. Patulin accumulation in apples by Penicillium expansum during postharvest stages. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 44, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomão, B.C.; Aragao, G.M.; Churey, J.J.; Padilla-Zakour, O.I.; Worobo, R.W. Influence of storage temperature and apple variety on patulin production by Penicillium expansum. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaro, D.; Lorè, A.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. A new strain of Metschnikowia fructicola for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on four cultivars of apple. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 75, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V.; Marín, S. Intraspecific variability of growth and patulin production of 79 Penicillium expansum isolates at two temperatures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 151, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, J.; Peeler, J. Effect of pH on the thermal destruction kinetics of patulin in aqueous solution. J. Food Sci. 1973, 38, 1094–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welke, J.E.; Hoeltz, M.; Dottori, H.A.; Noll, I.B. Effect of processing stages of apple juice concentrate on patulin levels. Food Control 2009, 20, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janotová, L.; Čížková, H.; Pivoňka, J.; Voldřich, M. Effect of processing of apple puree on patulin content. Food Control 2011, 22, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, C. Maturity indices for apple and pear. Hortic. Rev. 2010, 13, 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, K.; Devlieghere, F.; Flyps, H.; Oosterlinck, M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Rajković, A.; Verlinden, B.; Nicolaï, B.; Debevere, J.; De Meulenaer, B. Influence of storage conditions of apples on growth and patulin production by Penicillium expansum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 119, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Lai, T.; Qin, G.; Tian, S. Ambient pH stress inhibits spore germination of Penicillium expansum by impairing protein synthesis and folding: A proteomic-based study. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 9, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusky, D.; McEvoy, J.L.; Saftner, R.; Conway, W.S.; Jones, R. Relationship between host acidification and virulence of Penicillium spp. on apple and citrus fruit. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, S.; Zhou, T.; McGarvey, B.D. Comparative metabolomic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during the degradation of patulin using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarchelier, A.; Mujahid, C.; Racault, L.; Perring, L.; Lancova, K. Analysis of patulin in pear-and apple-based foodstuffs by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7659–7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Determination of trace patulin in apple-based food matrices. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katerere, D.R.; Stockenström, S.; Shephard, G.S. HPLC-DAD method for the determination of patulin in dried apple rings. Food Control 2008, 19, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.; Grauwet, T.; Santiago, J.S.; Tomic, J.; Vervoort, L.; Hendrickx, M.; Van Loey, A. Quality changes of pasteurised orange juice during storage: A kinetic study of specific parameters and their relation to colour instability. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mohammadi, A.; Tavakoli, R.; Kamankesh, M.; Rashedi, H.; Attaran, A.; Delavar, M. Enzyme-assisted extraction and ionic liquid-based dispersive liquid–liquid microextraction followed by high-performance liquid chromatography for determination of patulin in apple juice and method optimization using central composite design. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 804, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadok, I.; Stachniuk, A.; Staniszewska, M. Developments in the monitoring of patulin in fruits using liquid chromatography: An overview. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, K.; De Meulenaer, B.; Kasase, C.; Huyghebaert, A.; Ooghe, W.; Devlieghere, F. Free and bound patulin in cloudy apple juice. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1278–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appell, M.; Dombrink-Kurtzman, M.A.; Kendra, D.F. Comparative study of patulin, ascladiol, and neopatulin by density functional theory. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2009, 894, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaclavikova, M.; Dzuman, Z.; Lacina, O.; Fenclova, M.; Veprikova, Z.; Zachariasova, M.; Hajslova, J. Monitoring survey of patulin in a variety of fruit-based products using a sensitive UHPLC–MS/MS analytical procedure. Food Control 2015, 47, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, E.; Baars, A.; Biesebeek, J.T.; Oomen, A.; Bakker, M.; De Heer, C. Risk assessment of patulin intake from apple containing products by young children. World Mycotoxin J. 2012, 5, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, E.; Yin, S.; Fan, L.; Hu, H. Methylseleninic acid prevents patulin-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity via the inhibition of oxidative stress and inactivation of p53 and MAPKs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 5299–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maidana, L.; Gerez, J.R.; El Khoury, R.; Pinho, F.; Puel, O.; Oswald, I.P.; Bracarense, A.P.F. Effects of patulin and ascladiol on porcine intestinal mucosa: An ex vivo approach. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 98, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Assunção, R.; Alvito, P.; Kleiveland, C.; Lea, T. Characterization of in vitro effects of patulin on intestinal epithelial and immune cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 250, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Singh, N.; Ansari, K.M. Toxicological effects of patulin mycotoxin on the mammalian system: An overview. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 6, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puel, O.; Galtier, P.; Oswald, I.P. Biosynthesis and toxicological effects of patulin. Toxins 2010, 2, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannous, J.; Snini, S.P.; El Khoury, R.; Canlet, C.; Pinton, P.; Lippi, Y.; Alassane-Kpembi, I.; Gauthier, T.; El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A. Patulin transformation products and last intermediates in its biosynthetic pathway, E-and Z-ascladiol, are not toxic to human cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 2455–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castoria, R.; Mannina, L.; Durán-Patrón, R.; Maffei, F.; Sobolev, A.P.; De Felice, D.V.; Pinedo-Rivilla, C.; Ritieni, A.; Ferracane, R.; Wright, S.A. Conversion of the mycotoxin patulin to the less toxic desoxypatulinic acid by the biocontrol yeast Rhodosporidium kratochvilovae strain LS11. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11571–11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Feussner, K.; Wu, T.; Yan, F.; Karlovsky, P.; Zheng, X. Detoxification of mycotoxin patulin by the yeast Rhodosporidium paludigenum. Food Chem. 2015, 179, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawar, S.; Vevers, W.; Karieb, S.; Ali, B.K.; Billington, R.; Beal, J. Biotransformation of patulin to hydroascladiol by Lactobacillus plantarum. Food Control 2013, 34, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianiri, G.; Pinedo, C.; Fratianni, A.; Panfili, G.; Castoria, R. Patulin degradation by the biocontrol yeast Sporobolomyces sp. is an inducible process. Toxins 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliege, R.; Metzler, M. Electrophilic properties of patulin. N-acetylcysteine and glutathione adducts. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000, 13, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Melo, F.T.; de Oliveira, I.M.; Greggio, S.; Dacosta, J.C.; Guecheva, T.N.; Saffi, J.; Henriques, J.A.P.; Rosa, R.M. DNA damage in organs of mice treated acutely with patulin, a known mycotoxin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3548–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfenning, C.; Esch, H.L.; Fliege, R.; Lehmann, L. The mycotoxin patulin reacts with DNA bases with and without previous conjugation to GSH: Implication for related α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds? Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schebb, N.H.; Faber, H.; Maul, R.; Heus, F.; Kool, J.; Irth, H.; Karst, U. Analysis of glutathione adducts of patulin by means of liquid chromatography (HPLC) with biochemical detection (BCD) and electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahfoud, R.; Maresca, M.; Garmy, N.; Fantini, J. The mycotoxin patulin alters the barrier function of the intestinal epithelium: Mechanism of action of the toxin and protective effects of glutathione. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002, 181, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Yuan, Y.; Yue, T.; Hatab, S.; Wang, Z. Binding mechanism of patulin to heat-treated yeast cell. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 55, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Cao, J.; Zhang, X.; Apaliya, M.T. The possible mechanisms involved in degradation of patulin by Pichia caribbica. Toxins 2016, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwahashi, Y.; Hosoda, H.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Suzuki, Y.; Kitagawa, E.; Murata, S.M.; Jwa, N.-S.; Gu, M.-B.; Iwahashi, H. Mechanisms of patulin toxicity under conditions that inhibit yeast growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1936–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Iwahashi, Y. Gene expression profiles of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae sod1 caused by patulin toxicity and evaluation of recovery potential of ascorbic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7145–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp, G.; Horváth, E.; Mike, N.; Gazdag, Z.; Belágyi, J.; Gyöngyi, Z.; Bánfalvi, G.; Hornok, L.; Pesti, M. Regulation of patulin-induced oxidative stress processes in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3792–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianiri, G.; Idnurm, A.; Wright, S.A.; Durán-Patrón, R.; Mannina, L.; Ferracane, R.; Ritieni, A.; Castoria, R. Searching for genes responsible for patulin degradation in a biocontrol yeast provides insight into the basis for resistance to this mycotoxin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3101–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, H.-M.; Wang, X.; Li, B.-Q.; Long, M.-Y.; Tian, S.-P. Biodegradation mechanisms of patulin in Candida guilliermondii: An iTRAQ-Based proteomic analysis. Toxins 2017, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S. Patulin—A Chemical Concern for Apple Producers & Processors; OMAFRA (Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs): Guelph, ON, Canada, 2016.

- OMAFRA. Notes on Apple Diseases: Blue Mould and Grey Mould in Stored Apples; OMFRA (Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs): Guelph, ON, Canada, 2006.

- Tahir, I.I.; Nybom, H. Tailoring organic apples by cultivar selection, production system, and post-harvest treatment to improve quality and storage life. HortScience 2013, 48, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xiao, C. Characterization of fludioxonil-resistant and pyrimethanil-resistant phenotypes of Penicillium expansum from apple. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Capdeville, G.; Beer, S.V.; Watkins, C.B.; Wilson, C.L.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Aist, J.R. Pre-and post-harvest harpin treatments of apples induce resistance to blue mold. Plant Dis. 2003, 87, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Usall, J.; Teixido, N.; Eribe, X.O.d.; Vinas, I. Control of post-harvest decay of apples by pre-harvest and post-harvest application of ammonium molybdate. Pest Manag. Sci. 2001, 57, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadoni, A.; Guidarelli, M.; Phillips, J.; Mari, M.; Wisniewski, M. Transcriptional profiling of apple fruit in response to heat treatment: Involvement of a defense response during Penicillium expansum infection. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 101, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, M.; Jouybari, H.A.; Mesbahi, G.; Farahnaky, A.; Amiri, S. Effect of hot acetic acid solutions on postharvest decay caused by Penicillium expansum on Red Delicious apples. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 126, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, D.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. Control of Penicillium expansum and Botrytis cinerea on apple combining a biocontrol agent with hot water dipping and acibenzolar-S-methyl, baking soda, or ethanol application. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2004, 33, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Yu, T.; Guo, S.; Hu, H.; Zheng, X.; Karlovsky, P. Effect of the yeast Rhodosporidium paludigenum on postharvest decay and patulin accumulation in apples and pears. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahunu, G.K.; Zhang, H.; Apaliya, M.T.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L. Bamboo leaf flavonoid enhances the control effect of Pichia caribbica against Penicillium expansum growth and patulin accumulation in apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 141, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaini, V.; Zjalic, S.; Reverberi, M.; Fanelli, C.; Fabbri, A.; Del Fiore, A.; De Rossi, P.; Ricelli, A. Lentinula edodes enhances the biocontrol activity of Cryptococcus laurentii against Penicillium expansum contamination and patulin production in apple fruits. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 138, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanzani, S.M.; De Girolamo, A.; Schena, L.; Solfrizzo, M.; Ippolito, A.; Visconti, A. Control of Penicillium expansum and patulin accumulation on apples by quercetin and umbelliferone. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 228, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, C.; Wang, G. Effects of β-aminobutyric acid on control of postharvest blue mould of apple fruit and its possible mechanisms of action. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 61, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funes, G.J.; Gómez, P.L.; Resnik, S.L.; Alzamora, S.M. Application of pulsed light to patulin reduction in McIlvaine buffer and apple products. Food Control 2013, 30, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avsaroglu, M.; Bozoglu, F.; Alpas, H.; Largeteau, A.; Demazeau, G. Use of pulsed-high hydrostatic pressure treatment to decrease patulin in apple juice. High Press Res. 2015, 35, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Zhou, T.; Koutchma, T.; Wu, F.; Warriner, K. High hydrostatic pressure assisted degradation of patulin in fruit and vegetable juice blends. Food Control 2016, 62, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Koutchma, T.; Warriner, K.; Shao, S.; Zhou, T. Kinetics of patulin degradation in model solution, apple cider and apple juice by ultraviolet radiation. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2013, 19, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Meng, X.; Wang, D. Effective biosorption of patulin from apple juice by cross-linked xanthated chitosan resin. Food Control 2016, 63, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Liu, B. Biodegradation of mycotoxin patulin in apple juice by calcium carbonate immobilized porcine pancreatic lipase. Food Control 2018, 88, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Z. Biosorption of patulin from apple juice by caustic treated waste cider yeast biomass. Food Control 2013, 32, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silici, S.; Karaman, K. Inhibitory effect of propolis on patulin production of Penicillium expansum in apple juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 38, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, E.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, D. Patulin degradation in apple juice using ozone detoxification equipment and its effects on quality. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, e13645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Bai, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, N.; Ma, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Jiao, C.; Legall, N.; Mao, L. Genome re-sequencing reveals the history of apple and supports a two-stage model for fruit enlargement. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutot, M.; Nelson, L.; Tyson, R. Predicting the spread of postharvest disease in stored fruit, with application to apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 85, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.I.; Johansson, E.; Olsson, M.E. Improving the productivity, quality, and storability of ‘Katja’apple by better orchard management procedures. HortScience 2008, 43, 725–729. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wen, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Liao, Y. Mulching practices altered soil bacterial community structure and improved orchard productivity and apple quality after five growing seasons. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 172, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Børve, J.; Røen, D.; Stensvand, A. Harvest time influences incidence of storage diseases and fruit quality in organically grown ‘Aroma’apples. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 78, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Qi, X.; He, L. Effects of quercetin on postharvest blue mold control in kiwifruit. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 228, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, M.; Ederli, L.; Pasqualini, S.; Zazzerini, A. Biological control agents and chemical inducers of resistance for postharvest control of Penicillium expansum Link. on apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 59, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, H.; Marín, S.; Centelles, X.; Ramos, A.J.; Sanchis, V. Cold and ambient deck storage prior to processing as a critical control point for patulin accumulation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 116, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittemann, D.; McCormick, R.; Neuwald, D.A. Effect of high temperature and 1-MCP application or dynamic controlled atmosphere on energy savings during apple storage. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2015, 80, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, A.; Delong, J.; Arul, J.; Prange, R. The trend toward lower oxygen levels during apple (Malus × domestica Borkh) storage. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, K.; Devlieghere, F.; Amiri, A.; De Meulenaer, B. Evaluation of strategies for reducing patulin contamination of apple juice using a farm to fork risk assessment model. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 154, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paiva, E.; Serradilla, M.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Córdoba, M.; Villalobos, M.; Casquete, R.; Hernández, A. Combined effect of antagonistic yeast and modified atmosphere to control Penicillium expansum infection in sweet cherries cv. Ambrunés. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 241, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, H.; Marco, P.; Blanco, D.; Oria, R.; Venturini, M. Potential of a new strain of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BUZ-14 as a biocontrol agent of postharvest fruit diseases. Food Microbiol. 2017, 63, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, L.S.; Beacham-Bowden, T.; Keller, S.E.; Adhikari, C.; Taylor, K.T.; Chirtel, S.J.; Merker, R.I. Apple quality, storage, and washing treatments affect patulin levels in apple cider. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.; Long, M. Fate of patulin in the presence of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Food Addit. Contam. 2002, 19, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Mahunu, G.K.; Castoria, R.; Apaliya, M.T.; Yang, Q. Augmentation of biocontrol agents with physical methods against postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yue, T. Synthesis and characterization of nontoxic chitosan-coated Fe3O4 particles for patulin adsorption in a juice-pH simulation aqueous. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Guo, M.; Zhang, S.; Qin, D.; Yang, Y.; Li, M. Assessment of patulin adsorption efficacy from aqueous solution by water-insoluble corn flour. J. Food Saf. 2018, 38, e12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaiel, A.A.; Bassyouni, R.H.; Kamel, Z.; Gabr, S.M. Detoxification of patulin by Kombucha tea culture. CYTA-J. Food 2016, 14, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Guha, P. Use of predictive model to describe sporicidal and cell viability efficacy of betel leaf (Piper betle L.) essential oil on Aspergillus flavus and Penicillium expansum and its antifungal activity in raw apple juice. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 80, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinidou, S.; Floros, J.; LaBorde, L. Kinetics of the thermal degradation of patulin in the presence of ascorbic acid. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, T108–T114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jard, G.; Liboz, T.; Mathieu, F.; Guyonvarc’h, A.; Lebrihi, A. Review of mycotoxin reduction in food and feed: From prevention in the field to detoxification by adsorption or transformation. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2011, 28, 1590–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Zhou, T.; Wu, T.; Li, X. Saccharomyces cerevisiae YE-7 reduces the risk of apple blue mold disease by inhibiting the fungal incidence and patulin biosynthesis. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Ren, R. Efficacy of Pichia caribbica in controlling blue mold rot and patulin degradation in apples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 162, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricelli, A.; Baruzzi, F.; Solfrizzo, M.; Morea, M.; Fanizzi, F. Biotransformation of patulin by Gluconobacter oxydans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, R.L.; Hirkala, D.L.; Nelson, L.M. Postharvest biological control of blue mold of apple by Pseudomonas fluorescens during commercial storage and potential modes of action. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 133, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, M.; Cai, R. A new insight into the adsorption mechanism of patulin by the heat-inactive lactic acid bacteria cells. Food Control 2015, 50, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, H.A.; Awny, N.M.; Fahmy, H.M. Influence of environmental conditions of atoxigenic Aspergillus flavusHFB1 on biocontrol of patulin produced by a novel apple contaminant isolate, A. terreusHAP1, in vivo and in vitro. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 12, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Jiang, W.; Li, C.; Ma, N.; Xu, Y.; Meng, X. Patulin biodegradation by marine yeast Kodameae ohmeri. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2015, 32, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yue, T. Biocontrol activity and patulin-removal effects of Bacillus subtilis, Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Agrobacterium tumefaciens against Penicillium expansum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 1384–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topcu, A.; Bulat, T.; Wishah, R.; Boyacı, I.H. Detoxification of aflatoxin B1 and patulin by Enterococcus faecium strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 139, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.; Li, H.Y.; Zheng, X.D. Synergistic effect of chitosan and Cryptococcus laurentii on inhibition of Penicillium expansum infections. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 114, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Qian, J. Phytic acid enhances biocontrol activity of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa against Penicillium expansum contamination and patulin production in apples. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Product | Country | Year of Samples | Number of Samples (Positive/Total Samples) | Range (µg/kg or µg/L) | Percentage of Samples over 50 µg/L Patulin (10 µg/L for Children’s Food) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple | Pakistan (Punjab) | 2017 | 27/36 | <LOD–630.8 | 55.6% | [17] |

| Apple juice (including organic and conventional apple juice and juice concentrate) | China (Changchun) | 2009 | ND/35 | <1.2–94.7 | 20% | [12] |

| China (Shaanxi) | 2008–2010 | 568/574 | 2.5–22.7 | 0 | [13] | |

| China (Hangzhou) | 2015 | ND/4 | <LOD–16.8 | 0 | [18] | |

| Portugal (Lisbon) | 2007–2009 | 28/68 a | <LOD–42 | 0 | [19] | |

| Spain (Navarra) | ND | 25/100 | <LOD–118.70 | 11% | [20] | |

| Spain (Catalonia) | 2010–2011 | 21/47 a | <LOD–36.5 | 0 | [21] | |

| Serbia (Novi Sad) | 2013–2015 | 54/73 | <LOD–65.4 | 1.4% | [22] | |

| Argentina | 2005–2013 | 1866/4634 | <LOD–19,622 | 0.8% | [23] | |

| Pakistan (Punjab) | 2017 | 15/29 | <LOD–120.5 | 6.90% | [17] | |

| Tunisia | 2011 | 11/30 | 0–167 | ND | [24] | |

| Malaysia | 2012–2013 | 1/13 | <LOD–26.9 | 0 | [25] | |

| Apple jam/marmalade | China (Hangzhou) | 2015 | ND/4 | <LOD–11.0 | 0 | [18] |

| Argentina | ND | 6/26 | 17–39 | ND | [26] | |

| Apple puree/apple pulp | Argentina | ND | 4/8 | 22–221 | ND | [26] |

| Spain (Catalonia) | 2010–2011 | 6/46 a | <LOD–50.3 | 2.1% | [21] | |

| China (Changchun) | 2009 | ND/30 | <1.2–67.3 | 36.7% | [12] | |

| Products for babies (including apple juice, apple sauce, and compotes) | Italy | 2008–2009 | 22/60 | 3–9 | 0 | [27] |

| Italy (Campania) | ND | 0/26 | 0 | 0 | [28] | |

| Tunisia | 2011 | 7/25 | 0–165 | 28% | [24] | |

| Portugal (Lisbon) | 2007–2009 | 5/76 | <LOD–5.7 | 0 | [19] | |

| Spain | 2008 | 0/17 | 0 | 0 | [29] |

| Compound | Structure | Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Toxicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patulin |  | C7H6O4 | 152.14 | Cytotoxic, teratogenicity, mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, and immunotoxicity | [104,105] |

| E-ascladiol |  | C7H8O4 | 156.14 | 30 µM, no cytotoxic to Caco-2 | [105] |

| Z-ascladiol |  | C7H8O4 | 156.14 | 30 µM, slight cytotoxic to Caco-2 (20% decrease in cellular proliferation) | [105] |

| Desoxypatulinic acid |  | C7H8O4 | 156.14 | 50 and 100 µM, slight cytotoxic to human hepatocytes LO2 | [106,107] |

| Hydroascladiol |  | C7H10O4 | ND | ND | [108] |

| Category | Method | Description | Type of Apple Products | P. expansum Spore Suspension (spores/mL) | Blue Mold Decay Incidence | Patulin Content | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | ||||||

| Orchard | Spray elicitor | Harpin (80 mg/L) | McIntosh apple | 5 × 103 | 70% | 30% | ND | ND | [126] |

| Empire apple | 32% | 5–10% | ND | ND | |||||

| Red Delicious apple | 30% | 4% | ND | ND | |||||

| Ammonium molybdate (1 mM) | Golden Delicious apple | 1 × 104 | 49% | 35% | ND | ND | [127] | ||

| Before P. expansum inoculation | Heat treatment | Hot water dipping (45 °C, 10 min) | Ultima Gala apple | 1 × 104 | >80% | 0% | ND | ND | [128] |

| P. expansum inoculation, then hot water dipping (2% acetic acid, 50 °C, 3 min) | Red Delicious apple | 1 × 105 | 73.8% | 2.2% | ND | ND | [129] | ||

| Biocontrol agents | Metschnikowia pulcherrima BIO126 (108 cell/mL) | Golden Delicious apple | 1 × 105 | 100% | 56.6% | ND | ND | [130] | |

| M. pulcherrima BIO126 (108 cell/mL) with 10% ethanol | 100% | 52.3% | ND | ND | |||||

| M. pulcherrima BIO126 (108 cell/mL) with 3.0% sodium bicarbonate | 100% | 56.2% | ND | ND | |||||

| Rhodosporidium paludigenum (107 cell/mL) | Fuji apple | 1 × 105 | 100% | 67% | 0.001 mg/kg | 0.03 mg/kg | [131] | ||

| Pichia caribbica (1 × 108 cells/mL) | Fuji apple | 1 × 105 | ND | ND | 29 mg/kg | 2 mg/kg | [132] | ||

| Cryptococcus laurentii LS28 (1 × 106 cells/mL) and Lentinula edodes LF23 (2% w/v) | Golden delicious apple | 1 × 104 | 100% | 0 | 0.47 mg/kg | 0.005 mg/kg | [133] | ||

| Metschnikowia fructicola AL27 (1 × 108 cells/mL) | Golden delicious apple | 1 × 105 | ND | ND | >1 mg/kg | 0 mg/kg | [80] | ||

| Natural chemicals | Quercetin or umbelliferone (100 μg) | Golden Delicious apple | 5 × 104 | 100% | 8% or 14% | 65 mg/kg | 42 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg | [134] | |

| Bamboo leaf flavonoid (0.01% w/v) | Fuji apple | 1 × 105 | ND | ND | 29 mg/kg | 2 mg/kg | [132] | ||

| Spray elicitor | β-Aminobutyric acid (50 mM) | Golden Delicious apple | 1 × 104 | 100% | 36.6% | ND | ND | [135] | |

| Ammonium molybdate (5 mM) | Golden Delicious apple | 1 × 104 | 88% | 9% | ND | ND | [127] | ||

| M. pulcherrima BIO126 (108 cell/mL) and acibenzolar-S-methyl (1 mg/mL) | Golden Delicious apple | 1 × 105 | 100% | 57.4% | ND | ND | [130] | ||

| After P. expansum inoculation | Heat treatment | Hot water dipping (45 °C, 10 min) | Ultima Gala apple | 1 × 104 | 90% | 60% | ND | ND | [128] |

| Non-thermal processing | Pulsed light (35.8 J/cm2, 30 s) | Apple juice | ND | ND | ND | 129 mg/L | 22.38 mg/L | [136] | |

| Pulsed light (11.9 J/cm2, 20 s) | Apple puree | ND | ND | ND | 90 mg/kg | <LOD | |||

| High hydrostatic pressure (400 MPa, 30 °C, 5 min) | Apple juice | ND | ND | ND | 0.05 mg/L | 0.024 mg/L | [137] | ||

| High hydrostatic pressure (600 MPa, 5 min) | Apple and spinach juice | ND | ND | ND | 0.2 mg/L | 0.157 mg/L | [138] | ||

| UV (253.7 nm, 3.00 mW/cm2, 40 min) | Apple cider | ND | ND | ND | 1 mg/L | 0.125 mg/L | [139] | ||

| Apple juice without ascorbic acid | ND | ND | ND | 1 mg/L | 0.052 mg/L | ||||

| Apple juice with ascorbic acid | ND | ND | ND | 1 mg/L | 0.014 mg/L | ||||

| Adsorption | Cross-linked xanthated chitosan resin (pH 4, 30 °C, 18 h, 0.01 g) | Apple juice | ND | ND | ND | 300 mg/L | 170 mg/L | [140] | |

| Calcium carbonate immobilized porcine pancreatic lipase (40 °C, 18 h, 0.03 g/mL) | Apple juice | ND | ND | ND | 1 mg/L | <0.3 mg/L | [141] | ||

| Caustic treated waste cider yeast biomass | Apple juice | ND | ND | ND | 0.1 mg/L | 0.04 mg/L | [142] | ||

| Natural chemicals | Propolis (2 mg/mL) | Fresh pressed apple juice | 0.4 × 104~5 × 104 | ND | ND | 0.056 mg/L | 0.028 mg/L | [143] | |

| Gaseous ozone (12 mg/L, 10 min) | Apple juice | ND | ND | ND | 0.247 mg/L | 0.018 mg/L | [144] | ||

| Strain Type | Strain Name | Strain No. and Source | Active Component and Efficacy | Degrading Condition | Degradation Product | Degradation Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | S288C; obtained from ATCC (ATCC no. 204508) | Fermentation broth, 3.8 mg/L to 0 mg/L | 3.8 ppm PAT; Static Culture, 30 °C, 110 h | E-ascladiol and Z-ascladiol | ND | [89] |

| Pichia caribbica | Unsprayed orchard beside Yangtze River, China | Cell-free filtrate, 20 mg/L to 0 mg/L | NYDA/NYDB, 190 rpm, 28 °C, 48 h, | ND | Intracellular and extracellular enzymes | [116] | |

| Candida guilliermondii | Strain 2.63; Obtained from Institute of Microbiology (Chinese Academy of Science) | Live cells, 50 mg/L to 4 mg/L | NYDB media, 28 °C, 200 rpm, 36 h | E-ascladiol | A short-chain dehydrogenase (GI: 190348612) | [121] | |

| Rhodosporidium kratochvilovae | LS11; Isolated from olive tree (Italy) | Live cells, 150 mg/L to 3.7 mg/L | LiBa media, 23 °C, 150 rpm, 72 h | DPA | ND | [106] | |

| Rhodosporidium paludigenum | No. 394084; Isolated from South China Sea, preserved by CABI (the U.K.) | Intracellular enzyme, 10 mg/L to 0 mg/L | NYDB media, 28 °C 150 rpm, 48 h | DPA | Biological degradation and physical adsorption | [131] | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii | LS28; Isolated from “Annurca” apples in Molise (Italy) | Live cells, 0.41 mg/kg to 0.08 mg/kg | LiBa media, 25 °C, shaking, 144 h | ND | ND | [133] | |

| Sporobolomyces sp. | IAM 13481; obtained from FGSC (USA) | Live cells, 100 mg/L to 0 mg/L | LiBa media, 24 °C, shaking, 240 h | DPA, E-ascladiol and Z-ascladiol | Biological degradation, enzymatic reaction | [120] | |

| Metschnikowia fructicola | AL27; Isolated from “Golden Delicious” apples (Italy) | Live cells, 56.4 mg/kg to 0 mg/kg | YEMS media, 22 °C, 100 rpm, 168 h | ND | Competition for nutrients | [80] | |

| Kodameae ohmeri | HYJM25; Isolated from seawater and guts of marine animals | Live cells, 10 mg/L to 0.4 mg/L | YEPD media (pH 4), 28 °C, 100 rpm, 24 h | E-ascladiol and Z-ascladiol | Might be enzymatic reaction | [173] | |

| Bacteria | Gluconobacter oxydans | M8; Isolated from apples with blue-spot in Bari (Italy) | Live cells, 10 mg/L to 0.39 mg/L | PDB media, 30 °C, 175 rpm, 72 h | E-ascladiol and Z-ascladiol | ND | [169] |

| Bacillus subtilis | No. 10034; Obtained from CICC (China) | Live cells, 5 mg/L to 0.15 mg/L | Nutrient broth, 25 °C, 150 rpm, dark, 24 h | ND | ND | [174] | |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | No. 1.2182; Obtained from CGMCC (China) | Live cells, 5 mg/L to 1.93 mg/L | Seed broth, 25 °C, 150 rpm, dark, 24 h | ND | ND | [174] | |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | No. 1.2554; Obtained from CGMCC (China) | Live cells, 5 mg/L to 3.45 mg/L | Seed broth, 25 °C, 150 rpm, dark, 24 h | ND | ND | [174] | |

| Probiotics | Lactobacillus plantarum | S1; isolated from fermented animal feeds | Cell free supernatant, 100 mg/L to 0 mg/L | MRS broth, 37 °C, 4 h | E-ascladiol, Z-ascladiol, and hydroascladiol | ND | [108] |

| Lactobacillus brevis | LB-20023; Obtained from CICC (China) | Heat-inactivated cells, 4 mg/L to 1.4 mg/L | MRS media, 37 °C, 150 rpm, 48 h | ND | Binding by polysaccharides and proteins from cell wall | [171] | |

| Enterococcus faecium | EF031; Obtained from Aroma-Prox (Cedex, France) | Live cells, 1 mg/L to 0.547 mg/L | BHI broth (pH 4), 37 °C, soft agitation, 48 h | ND | Binding | [175] | |

| Fungus | Aspergillus flavus | HF-B1; Isolated from fruits in Egypt | Live cells, 324 mg/L to 34 mg/L | PDB medium, 30 °C, 240 h | ND | ND | [172] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, L.; Carere, J.; Lu, Z.; Lu, F.; Zhou, T. Patulin in Apples and Apple-Based Food Products: The Burdens and the Mitigation Strategies. Toxins 2018, 10, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10110475

Zhong L, Carere J, Lu Z, Lu F, Zhou T. Patulin in Apples and Apple-Based Food Products: The Burdens and the Mitigation Strategies. Toxins. 2018; 10(11):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10110475

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Lei, Jason Carere, Zhaoxin Lu, Fengxia Lu, and Ting Zhou. 2018. "Patulin in Apples and Apple-Based Food Products: The Burdens and the Mitigation Strategies" Toxins 10, no. 11: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10110475

APA StyleZhong, L., Carere, J., Lu, Z., Lu, F., & Zhou, T. (2018). Patulin in Apples and Apple-Based Food Products: The Burdens and the Mitigation Strategies. Toxins, 10(11), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins10110475