Parent of Origin Effects on Family Communication of Risk in BRCA+ Women: A Qualitative Investigation of Human Factors in Cascade Screening

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Template Theme 1: ‘Gender Scripting’

2.2. Template Theme 2: ‘Family Dynamics’

2.3. Template Theme 3: ‘Medical Biases’

2.4. Mapping Template Themes and Sub-Codes to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

3. Discussion

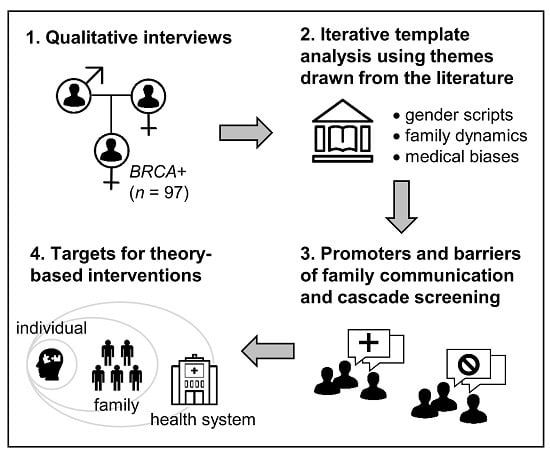

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants and Procedures

4.2. Analysis

4.3. Theoretical Framework

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harbeck, N.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Cortes, J.; Gnant, M.; Houssami, N.; Poortmans, P.; Ruddy, K.; Tsang, J.; Cardoso, F. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiovitz, S.; Korde, L.A. Genetics of breast cancer: A topic in evolution. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.J.; Jervis, S.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Force, U.S.P.S.T.; Owens, D.K.; Davidson, K.W.; Krist, A.H.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kubik, M.; et al. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2019, 322, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, M.C.; Dotson, W.D.; DeVore, C.S.; Bednar, E.M.; Bowen, D.J.; Ganiats, T.G.; Green, R.F.; Hurst, G.M.; Philp, A.R.; Ricker, C.N.; et al. Delivery Of Cascade Screening For Hereditary Conditions: A Scoping Review Of The Literature. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernholtz, S.; Laitman, Y.; Kaufman, B.; Paluch Shimon, S.; Friedman, E. Cancer risk in Jewish BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: Effects of oral contraceptive use and parental origin of mutation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 129, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senst, N.; Llacuachaqui, M.; Lubinski, J.; Lynch, H.; Armel, S.; Neuhausen, S.; Ghadirian, P.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A.; Hereditary Breast Cancer Study Group. Parental origin of mutation and the risk of breast cancer in a prospective study of women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Clin. Genet. 2013, 84, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellberg, C.; Jernstrom, H.; Broberg, P.; Borg, A.; Olsson, H. Impact of a paternal origin of germline BRCA1/2 mutations on the age at breast and ovarian cancer diagnosis in a Southern Swedish cohort. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2015, 54, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.R.; Oosterwijk, J.C.; Aalfs, C.M.; Rookus, M.A.; Adank, M.A.; van der Hout, A.H.; van Asperen, C.J.; Gomez Garcia, E.B.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Jager, A.; et al. Bias Explains Most of the Parent-of-Origin Effect on Breast Cancer Risk in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, D.G.; Harkness, E.; Lalloo, F. The BRCA1/2 Parent-of-Origin Effect on Breast Cancer Risk-Letter. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quillin, J.M.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Borzelleca, J.; Bodurtha, J.; Bowen, D.; Baer Wilson, D. Paternal relatives and family history of breast cancer. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 31, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozanne, E.M.; O’Connell, A.; Bouzan, C.; Bosinoff, P.; Rourke, T.; Dowd, D.; Drohan, B.; Millham, F.; Griffin, P.; Halpern, E.F.; et al. Bias in the reporting of family history: Implications for clinical care. J. Genet. Couns. 2012, 21, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.B.; Montgomery, S.; Bingler, R.; Ruth, K. Communicating genetic test results within the family: Is it lost in translation? A survey of relatives in the randomized six-step study. Fam. Cancer 2016, 15, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hesse-Biber, S.; Dwyer, A.A.; Yi, S. Parent of origin differences in psychosocial burden and approach to BRCA risk management. Breast J. 2019, 26, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.L.; Butow, P.N.; Vetsch, J.; Quinn, V.F.; Patenaude, A.F.; Tucker, K.M.; Wakefield, C.E. Family Communication, Risk Perception and Cancer Knowledge of Young Adults from BRCA1/2 Families: A Systematic Review. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nycum, G.; Avard, D.; Knoppers, B.M. Factors influencing intrafamilial communication of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer genetic information. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, E.; Taylor, N.; Greening, S.; Wakefield, C.E.; Warwick, L.; Williams, R.; Tucker, K. Quantifying family dissemination and identifying barriers to communication of risk information in Australian BRCA families. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieberman, S.; Lahad, A.; Tomer, A.; Koka, S.; BenUziyahu, M.; Raz, A.; Levy-Lahad, E. Familial communication and cascade testing among relatives of BRCA population screening participants. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J.; Ramon y Cajal, T.; Torres, A.; Darder, E.; Gadea, N.; Velasco, A.; Fortuny, D.; Lopez, C.; Fisas, D.; Brunet, J.; et al. Uptake of predictive testing among relatives of BRCA1 and BRCA2 families: A multicenter study in northeastern Spain. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehniger, J.; Lin, F.; Beattie, M.S.; Joseph, G.; Kaplan, C. Family communication of BRCA1/2 results and family uptake of BRCA1/2 testing in a diverse population of BRCA1/2 carriers. J. Genet. Couns. 2013, 22, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sermijn, E.; Delesie, L.; Deschepper, E.; Pauwels, I.; Bonduelle, M.; Teugels, E.; De Greve, J. The impact of an interventional counselling procedure in families with a BRCA1/2 gene mutation: Efficacy and safety. Fam. Cancer 2016, 15, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Cathain, A.; Croot, L.; Duncan, E.; Rousseau, N.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; Yardley, L.; Hoddinott, P. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Org. Behav. Hum. Dec. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Xie, T.; Zhang, W. Predicting women’s intentions to screen for breast cancer based on the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2019, 45, 2440–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivell, S.; Elwyn, G.; Edwards, A.; Manstead, A.S.; BresDex, G. Factors influencing the surgery intentions and choices of women with early breast cancer: The predictive utility of an extended theory of planned behaviour. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richards, I.; Tesson, S.; Porter, D.; Phillips, K.A.; Rankin, N.; Musiello, T.; Marven, M.; Butow, P. Predicting women’s intentions for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: An application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Masujima, M.; Kato, T.; Ikeda, S.I.; Shimizu, C.; Kinoshita, T.; Shiino, S.; Suzuki, M.; Mori, M.; Takahashi, M. Knowledge, fatigue, and cognitive factors as predictors of lymphoedema risk-reduction behaviours in women with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Carrera, P.; Parrott, W.G.; Gomez-Trillos, S.; Perera, R.A.; Sheppard, V.B. Applying the theory of planned behavior to examine adjuvant endocrine therapy adherence intentions. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katapodi, M.C.; Duquette, D.; Yang, J.J.; Mendelsohn-Victor, K.; Anderson, B.; Nikolaidis, C.; Mancewicz, E.; Northouse, L.L.; Duffy, S.; Ronis, D.; et al. Recruiting families at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer from a statewide cancer registry: A methodological study. Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, H.C.; Organista, K.; Burack, J.; Biesecker, B.B. Genetic susceptibility testing from a stress and coping perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1880–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Tenhunen, H.; Torkki, P.; Heinonen, S.; Lillrank, P.; Stefanovic, V. Considering medical risk information and communicating values: A mixed-method study of women’s choice in prenatal testing. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorwinden, J.S.; Buitenhuis, A.H.; Birnie, E.; Lucassen, A.M.; Verkerk, M.A.; van Langen, I.M.; Plantinga, M.; Ranchor, A.V. Expanded carrier screening: What determines intended participation and can this be influenced by message framing and narrative information? Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 25, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Biesecker, B.; Austin, J.; Caleshu, C. Theories for Psychotherapeutic Genetic Counseling: Fuzzy Trace Theory and Cognitive Behavior Theory. J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.L.; Butow, P.N.; Rhodes, P.; Tucker, K.M.; Williams, R.; Healey, E.; Wakefield, C.E. Talking across generations: Family communication about BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic cancer risk. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, T.; Heilman, M.E.; Peus, C.V. The Multiple Dimensions of Gender Stereotypes: A Current Look at Men’s and Women’s Characterizations of Others and Themselves. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Heijer, M.; Seynaeve, C.; Vanheusden, K.; Duivenvoorden, H.J.; Bartels, C.C.; Menke-Pluymers, M.B.; Tibben, A. Psychological distress in women at risk for hereditary breast cancer: The role of family communication and perceived social support. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, N.; Ardern-Jones, A.; Eeles, R.; Foster, C.; Lucassen, A.; Moynihan, C.; Watson, M. Communication about genetic testing in families of male BRCA1/2 carriers and non-carriers: Patterns, priorities and problems. Clin. Genet. 2005, 67, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, E.; Stopfer, J.E.; Burlingame, E.; Evans, K.G.; Nathanson, K.L.; Weber, B.L.; Armstrong, K.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Domchek, S.M. Factors determining dissemination of results and uptake of genetic testing in families with known BRCA1/2 mutations. Genet. Test. 2008, 12, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daly, M.B. The impact of social roles on the experience of men in BRCA1/2 families: Implications for counseling. J. Genet. Couns. 2009, 18, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, A.L.; Butow, P.N.; Tucker, K.M.; Wakefield, C.E.; Healey, E.; Williams, R. Challenges and strategies proposed by genetic health professionals to assist with family communication. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallowell, N.; Arden-Jones, A.; Eeles, R.; Foster, C.; Lucassen, A.; Moynihan, C.; Watson, M. Guilt, blame and responsibility: Men’s understanding of their role in the transmission of BRCA1/2 mutations within their family. Sociol. Health Illn. 2006, 28, 969–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iredale, R.; Brain, K.; Williams, B.; France, E.; Gray, J. The experiences of men with breast cancer in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, E.N.; Kaatz, A.; Carnes, M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaa, K.L.; Roter, D.L.; Biesecker, B.B.; Cooper, L.A.; Erby, L.H. Genetic counselors’ implicit racial attitudes and their relationship to communication. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, A.K.; Aliabadi-Wahle, S.; Beech, D.J. Physicians-in-training recommendations for prophylactic bilateral mastectomies. Breast J. 2003, 9, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwiter, R.; Rahm, A.K.; Williams, J.L.; Sturm, A.C. How can we reach at-risk relatives: Efforts to enhance communication and cascade testin guptake: A mini-review. Curr. Genet. Med. Rep. 2018, 6, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.B.; Chou, W.S.; Gaysynsky, A.; Krakow, M.; Elrick, A.; Khoury, M.J.; Kaphingst, K.A. Communication of cancer-related genetic and genomic information: A landscape analysis of reviews. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peipins, L.A.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Hawkins, N.A.; Soman, A.; White, M.C.; Hodgson, M.E.; DeRoo, L.A.; Sandler, D.P. Communicating with Daughters About Familial Risk of Breast Cancer: Individual, Family, and Provider Influences on Women’s Knowledge of Cancer Risk. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; McGlynn, E.A.; Safran, D.G. A Framework for Increasing Trust Between Patients and the Organizations That Care for Them. JAMA 2019, 321, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legare, F.; Robitaille, H.; Gane, C.; Hebert, J.; Labrecque, M.; Rousseau, F. Improving Decision Making about Genetic Testing in the Clinic: An Overview of Effective Knowledge Translation Interventions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwak, D.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kwon, Y.; Babiak, K. Exploring consumer response to a nationwide breast cancer awareness campaign: The case of the National Football League’s Crucial Catch campaign. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2019, 19, 208–232. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnayake, P.; Wakefield, C.E.; Meiser, B.; Suthers, G.; Price, M.A.; Duffy, J.; Kathleen Cuningham National Consortium for Research into Familial Breast; Tucker, K. An exploration of the communication preferences regarding genetic testing in individuals from families with identified breast/ovarian cancer mutations. Fam. Cancer 2011, 10, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stromsvik, N.; Raheim, M.; Oyen, N.; Engebretsen, L.F.; Gjengedal, E. Stigmatization and male identity: Norwegian males’ experience after identification as BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. J. Genet. Couns. 2010, 19, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse-Biber, S.; An, C. Genetic Testing and Post-Testing Decision Making among BRCA-Positive Mutation Women: A Psychosocial Approach. J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 25, 978–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, W.F. A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In Research Methods for Primary Care: Doing Qualitative Research; Crabtree, B.F., Miller, W.F., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 3, pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. Template Analysis. In Qualitative Methods and Analysis in Organizational Research: A Practical Guide; Symon, G., Cassell, C., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 118–134. [Google Scholar]

- King, N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Symon, G., Cassel, S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004; pp. 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryant, A.C.K. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographics Heading Title | Paternally Inherited Pathogenic BRCA Variant | Maternally Inherited Pathogenic BRCA Variant |

|---|---|---|

| race | ||

| white | 29 (85%) | 55 (92%) |

| other | 5 (15%) | 5 (8%) |

| age (years) | ||

| 18–30 | 7 (21%) | 14 (23%) |

| 31–40 | 12 (35%) | 27 (44%) |

| 41–50 | 11 (32%) | 13 (21%) |

| 51–60 | 3 (9%) | 7 (11%) |

| 60+ | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| education | ||

| <college | − | 1 (2%) |

| college | 17 (53%) | 39 (67%) |

| advanced degree | 15 (47%) | 18 (31%) |

| socioeconomic status | ||

| lower-middle class | 5 (18%) | 2 (4%) |

| middle class | 20 (71%) | 46 (84%) |

| upper class | 3 (11%) | 7 (12%) |

| Factors Promoting Intrafamilial Communication of Risk | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Code | Representative Quote |

| Fatherly protection | Participant 026 on her father’s motivation for testing: “[He said] if it wasn’t for you, I probably wouldn’t get tested. I gave you this mutation, I will help you financially as much as I can [...] don’t worry about it.” |

| Female camaraderie | Participant 023 on her paternal aunts who had been documenting family history for decades: “Luckily [my father] has six sisters and the three that survived were very, you know… proactive in making sure… in keeping all of their sisters’ records, and making sure all of the nieces and their daughters knew, and that… you know, we did see a GYN or OBGYN, and they knew our history going along. In my family, we were really lucky that we had a pretty solid documented history due to my aunts. If my father had six brothers instead of six sisters, we would never have known we had this [BRCA+].” |

| Factors Blocking Family Communication of Risk | |

| Sub-Code | Representative Quote |

| Male stoicism | Participant 002 on her father ’s lack of emotional expression and reluctance to discuss the family BRCA+ history: “He never really talks about it. I guess he’s never really wanted to know… and I get [it], I totally do understand that. I don’t… like, shame people who don’t want to know, because… I get it.” |

| Parental guilt | Participant 033 on her father’s guilt: “He apologized to me all the time. ‘I’m so sorry for what I did to you.’ And I, ‘Dad, you didn’t do anything to me.’ He goes, ‘I… ya know, I wish… I wish… ya know… I should’ve never had children if I had known’ blah, blah, blah. I said, ‘Are you kidding? Like, I’m so happy that you had me.’ I… I don’t, but he… he had tremendous guilt.” |

| Sub-Code | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Harmful negligence | Participant 030 on lack of urgency regarding BRCA despite multiple affected family members: “She [cousin] just acted like, you know, it was like… nothing. There’s just no communication. I mean, families like that don’t get back together again any more at Christmas, so nobody talks.” |

| Intra-family negligence | Participant 044 on invisible/unknown family history: “He [father] has a tremendous amount of guilt… he feels responsible that, we didn’t have this information sooner. I would never want to say it could have been prevented, but… you think about how we didn’t have a good relationship with his family… perhaps if we did… these conversations… more conversations would have taken place and we could’ve looked a little bit more into what that meant for us, you know?” |

| Active withdrawal of support | Participant 035 on her father urging her and the family to ‘move on with their lives’ and subsequently withdrawing support for her: “I think he became a real jerk about it too. He was just like, just move on… move on with your life already. And I think that’s cause he wanted to move on with his life like I think he felt really guilty for giving it to me.”— She goes on to explain how this resulted in family conflict and her mother subsequently squashing any conversation about BRCA to avoid upsetting her husband and sons. |

| Factors Contributing to Medical Biases | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Codes | Representative Quotes |

| Medical misconceptions | Participant 031 on her gynecologists genetic misconceptions regarding BRCA: “He had always told me that it was only the mom’s side that we needed to be worried about as far as family history… so that’s obviously not true.” |

| Medical minimizing | Participant 036 on her experiences not having medical professionals not considering her family history of a male diagnosed with breast cancer: “Even when I was diagnosed, which was in 2004, no one was concerned about the fact that I had a male relative [diagnosed with breast cancer] in terms of genetics.” |

| Factors Mitigating Biases | |

| Sub-Codes | Representative Quotes |

| Informed physicians | Participant 022 on her grandfathers’ medical provider being informed: “So when my grandfather had the breast cancer, his sister was actually struggling with breast and ovarian cancer at the same time…. and his doctor… given that (history], just brought up that… This is sort of a new finding that… since it’s so rare [breast cancer in a male], and since your sister has breast cancer at the same time… maybe you should be tested for your family’s sake, for this mutation. It’s completely free to get tested, and it might be useful information.” |

| Trust in healthcare | Participant 017 expressed her full trust in her healthcare providers when they assured her she was doing “enough” through aggressive surveillance: “When I go into see my… um, breast doctor… you know, I guess about every other time, you know, I say ‘Are you sure we don’t need to have my breasts removed?’ And he keeps reassuring me, I am telling you, everything we are doing… if you get cancer, we will catch it so early, so early, you are not going to have to… you are not going to die… you are not going to have to be worried about this. It’s going to be so early” |

| Interventions Targeting the Individual | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Codes | Potential Interventions |

| Fatherly protection (+) Male stoicism (−) | • Framing masculine role as the family protector (i.e., being a good father = sharing information to protect the family) |

| Interventions Targeting the Family Unit | |

| Sub-Codes | Potential Interventions |

| Female camaraderie (+) | • Empowering women to be a “BRCA informant” for the family to spread knowledge of risk through the family and highlighting the advantages of early detection and intervention • Genetic counseling to support recognition that genes and inheritance are beyond one’s individual control, reframe the focus to recognize that knowledge is powerful for enabling cascade screening, heightened surveillance and early risk-reducing interventions • Use family systems approach to “nudge” family members to rally around affected members |

| Harmful negligence (−) | |

| Intra-family ignorance (−) | |

| Paternal guilt (−) | |

| Active withdrawal of support (−) | |

| Interventions Targeting the Healthcare System | |

| Sub-Codes | Potential Interventions |

| Medical misconceptions (−) | • Continuing education (primary care providers, gynecologists) on genomic healthcare competencies (i.e., taking a three generation family history and assessing cancer risk from both sides of the family to enable cascade screening) • Uptake and implementation of U.S. Preventive Service Task Force recommendations for Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer |

| Medical minimizing (−) | |

| Informed physicians (+) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dwyer, A.A.; Hesse-Biber, S.; Flynn, B.; Remick, S. Parent of Origin Effects on Family Communication of Risk in BRCA+ Women: A Qualitative Investigation of Human Factors in Cascade Screening. Cancers 2020, 12, 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082316

Dwyer AA, Hesse-Biber S, Flynn B, Remick S. Parent of Origin Effects on Family Communication of Risk in BRCA+ Women: A Qualitative Investigation of Human Factors in Cascade Screening. Cancers. 2020; 12(8):2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082316

Chicago/Turabian StyleDwyer, Andrew A., Sharlene Hesse-Biber, Bailey Flynn, and Sienna Remick. 2020. "Parent of Origin Effects on Family Communication of Risk in BRCA+ Women: A Qualitative Investigation of Human Factors in Cascade Screening" Cancers 12, no. 8: 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082316

APA StyleDwyer, A. A., Hesse-Biber, S., Flynn, B., & Remick, S. (2020). Parent of Origin Effects on Family Communication of Risk in BRCA+ Women: A Qualitative Investigation of Human Factors in Cascade Screening. Cancers, 12(8), 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082316