1. Introduction

Metal-based catalysts have revolutionized synthetic chemistry, enabling challenging chemical reactions with exquisite stereochemical control [

1,

2]. Disadvantages of their frequent use, however, include high cost and potentially adverse environmental effects. As a result, chemists have explored biologically derived catalysts as less expensive and less toxic alternatives [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In particular, the pharmaceutical industry has adapted biocatalysts to “green” large-scale synthetic pathways [

3]. Numerous enzymes, for example, have been evolved to synthesize pharmaceutical compounds, or their intermediates, with high yields and enantiomeric excess, improving overall process efficiency and environmental compatibility [

4].

Lipases, a versatile class of biocatalysts, have undergone extensive study over the past two decades [

5]. They have been reported to function in non-aqueous media/organic solvents, possess catalytic activity towards a wide range of organic reactions, and provide recyclability via immobilization [

1,

5,

6,

7]. In their native (biological) setting, lipases catalyze the hydrolysis of esters from triacylglycerides. However, when placed under minimal or no-water conditions, they can catalyze various types of organic transformations such as Michael additions and aldol additions [

6,

8]. Catalysis of these non-native transformations by enzymes has been previously deemed “promiscuous” [

9,

10], a general descriptor for proteins that catalyze non-native transformations. Hult and Berglund previously defined three types of promiscuity: conditional (due to change in solvent, temperature, etc.); substrate (adaptable substrate specificity); and catalytic (accommodation of mechanistically distinct reactions) [

9]. The catalytic promiscuity of lipases has been the foundation on which various studies have been conducted to demonstrate a broad spectrum of lipase catalyzed organic transformations including the Robinson annulation, the Knoevenagel condensation, and the Morita–Baylis–Hillman reaction [

7,

11,

12]. Lipases derived from plant, animal, and fungal sources, or recombinantly expressed from a variety of host organisms, are readily commercially available and thus are an attractive source of new catalytic moieties.

Despite intensive investigation of lipase biocatalysis, unanswered questions remain regarding fundamental aspects of their propensity for promiscuous catalysis [

13]. Some studies have identified crude lipase preparations with biocatalytic properties presuming, but not demonstrating, that lipase, in particular the lipase active site responsible for the in vivo hydrolysis of fatty acids (

Figure 1A,B), is also responsible for promiscuous biocatalytic behavior observed in organic or aqueous/organic solvent mixtures (

Figure 1C) [

12,

14]. While in many instances the lipase activity present in crude lipase preparations is directly responsible for promiscuous catalysis, this is not always the case [

15,

16]. In the absence of a more thorough characterization of these catalytic moieties, it is challenging to improve on the initial findings through the now-standard means of rational design and/or directed evolution.

Our approach to the characterization of biocatalysts involved screening crude preparations for biocatalytic activity with mass spectrometry followed by reaction optimization (

Figure 1D). In addition, we utilized mass spectrometry for identification of the primary components of biocatalytic lipase preparations. This opens the possibility of improving reproducibility and further development of biocatalytic methods. In this work, we describe methods to screen lipase preparations for biocatalytic activity towards a synthetically useful target, the Wieland–Miescher ketone (

3 and

4,

Figure 1C), an important intermediate for the synthesis of biologically active compounds such as steroids, terpenoids, and taxol, via a one-pot Robinson annulation reaction. In the Robinson annulation, a Michael addition between a ketone and a methyl vinyl ketone is followed by an intramolecular aldol condensation to form a six-membered ring. We also describe how initial results from a mass spectrometry-based screen can be improved through a process of reaction optimization. We took lead catalysts from the screen and further characterized their proteinaceous components, identifying non-lipase proteins that are potentially responsible for the observed catalytic activity. The methodology and fundamental characterization of biocatalysts described in this report have general utility in the screening and identification of biocatalysts in numerous organic transformations.

2. Results

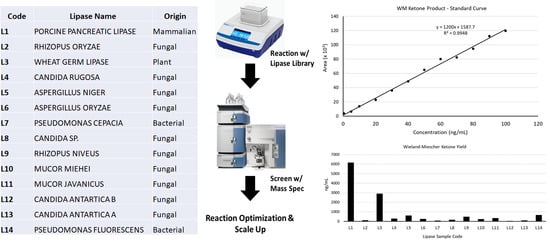

We began by assembling a 14-member library of commercially available lipases preparations, selecting lipases previously reported to catalyze C-C bond forming reactions (porcine pancreatic lipase,

Candida antarctica lipase B) [

11,

12,

14,

17], in addition to lipase preparations with unknown biocatalytic properties in promiscuous biocatalysis (Wheat germ lipase). Biocatalytic potential of the lipase library was then assessed for synthesis of the Wieland–Miescher ketone from methyl vinyl ketone and 2-methyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione using recently reported literature conditions [

12]. To rapidly assess biocatalytic potential of the library, an LC/MS method was developed (Materials and Methods) that detected only the main fragmentation pattern Wieland–Miescher ketone product (

Figure 2).

Reaction yields were determined for each lipase using a standard curve (

Figure 2C and

Table 1). While we were able to identify lipases (Entries 1, 3, and 5 in

Table 1) with biocatalytic activity, the yields were less than 1%, in contrast to a literature report using these conditions [

12]. As a result, we undertook optimization studies using our top hit from the screen (L1-PPL) to attempt better reaction yields.

To optimize this reaction, we turned to a previously described one-pot synthesis of WMK using L-proline in DMSO [

18]. Therefore, in these initial optimization studies, we switched to DMSO as the primary solvent and included L-proline as a positive control. In the optimization experiments, reaction yields were assessed using HPLC (

Figure 3C). We found that the PPL-catalyzed reaction in DMSO produced the triketone product

13 (

Figure 3A), whereas the L-proline reaction formed the expected WMK products

3 and

4 (

Figure 3A). We hypothesized that L-proline plays dual roles as a biocatalyst: one in which the amino acid promotes the necessary transition state for conversion of

13 to

14 through an aldol addition, and another in which the α-amino sidechain functions as a base to convert

14 to a mixture of products

3 and

4 through dehydration. Therefore, we reasoned that addition of a basic co-catalyst such as imidazole might better mimic the bi-functional L-Pro catalyst. We found that a combination of PPL and imidazole was able to produce a modest yield of

3 and

4 (

Figure 3 and

Table 2). By contrast, in reactions in which only PPL was present, or in which only imidazole was present, no WMK product was detected via HPLC (

Figure 3B and

Table 2). Interestingly, the combination of BSA and imidazole also resulted in an appreciable yield of product (

Table 2).

2.1. Reaction Optimization: Catalyst Loading, Solvent Effects, Enantiomeric Excess

Having identified the components necessary for forming modest amounts of WMK from protein and co-catalyst, we sought to further optimize the reaction by focusing on catalyst loading and solvent system. Setting up a series of reactions in DMSO, we varied catalyst loading from 5 to 35 mg/mL, finding that reaction yield increased up to 30 mg of catalyst per 1 mL reaction volume, but decreased with amounts in excess of 30 mg (

Table 3 and

Figure 4A). The observed decrease in yield with higher catalyst loading is largely due to an increased amount of insoluble, aggregated material from the crude lipase preparation in the reaction vials, which interferes with efficient mixing of the lipase and substrates. Note that mechanical stirring, rather than shaking, might reverse the observed trend. We then investigated reaction yields in solvents other than DMSO. Reactions in methanol produced similar yields to DMSO, yet reactions with increasingly longer chain alcohols (ethanol, propanol, butanol, and pentanol) steadily decreased reaction yields (

Table 3). Enantiomeric excess of the Wieland–Miescher ketone products produced with the lipase/imidazole system in DMSO were substantially lower than those produced with L-Proline (

Figure 4), whereas performing the PPL reaction in MeOH slightly improved enantiomeric excess. Reactions performed in longer chain alcohols also resulted in progressively lower enantiomeric excess (ee) values (

Table 3, Entries 6–9).

2.2. Reaction Optimization: Exploration of Co-Catalysts

We next investigated the effects of co-catalysts other than imidazole on reaction yield. Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), which is more nucleophilic but less basic than imidazole, gave a substantially lower yield (

Table 4, Entry 4). Alternately, ionic base co-catalysts sodium hydroxide and sodium bicarbonate gave less significantly reduced yields of WMK

2.3. Determination of Primary Components of Biocatalytic Preparations

Previous reports have demonstrated the presence of multiple biocatalytic entities present in commonly used lipase preparations [

19]. Having optimized our reaction conditions with crude lipase preparations, we sought to more precisely define their composition. We separated the crude PPL mixture on a size exclusion column, isolating two primary components (

Figure 5A). Bands were excised and subjected to proteolytic digest and subsequent characterization by mass spectrometry (see

Section 4). The higher molecular weight species was identified as porcine alpha-amylase, whereas the lower molecular weight species was identified as a porcine carboxypeptidase (both carboxypeptidases A1 and B were present in the analysis). Surprisingly, neither of the principle components of this commonly used lipase preparation was porcine pancreatic lipase. This is significant, since numerous reports use this preparation of porcine pancreatic lipase (Type II), and others without further purification [

12,

14,

20,

21]. A second lipase from our library with biocatalytic activity for WMK production (L3; wheat germ lipase) was also characterized by this method (

Figure 5B and

Supplementary Materials Figure S1). Again, none of the principle components of this preparation was identified as wheat germ lipase.

2.4. Reassessment of Biocatalytic Preparations with Optimized Reaction Conditions

Having identified optimized solvent, catalyst loading, and basic cofactor, we then rescreened our lipase library for biocatalytic activity towards WMK. In addition, as an outcome of this screen, we discovered that absorbance, in addition to mass spec, could be an effective means of screening for biocatalytic potential towards the WMK synthesis. In addition to select lipases from our initial screen, we also included commercially available proteins that were identified by proteomics as principal components of the crude PPL preparation (carboxypeptidase A (PA), carboxypeptidase B (PB), alpha amylase (P alphaS)) in addition to immobilized forms of

Candida antarctica lipase B (L12-acr and L12-imo). By correlating absorbance (350 nm) of the crude reaction mixture with reaction yield (

Figure 6A), we demonstrate a correlation between biocatalytic potential and yield of WMK. Furthermore, plotting absorbance (350 nm) versus percent yield reveals that applying a colorimetric cutoff of OD

350 = 1.0 would eliminate all of the reactions with yields below 10% (

Figure 6B). This indicates that colorimetric analysis could be a convenient basis for a large-scale screen of biocatalysts for WMK production.

A more in-depth analysis of reaction yields from this screen reveals that the biocatalysts identified in the initial LC/MS screen (L1, L3, L5, L9, and L14) also emerged as top biocatalysts in the colorimetric screen (

Figure 6 and

Table 5). In addition, alpha amylase alone, which was identified as a primary component of the PPL preparation, produced a significant yield of WMK. The yield did not match that of the crude PPL preparation, indicating that multiple proteinaceous components, including porcine pancreatic lipase, carboxypeptidases, and amylases, may be involved in the biocatalytic reaction. However, based on the ability of a non-lipase protein (BSA) and an individual amino acid (L-Pro) to promote product formation, we hypothesized that the endogenous catalytic activities of the component proteins were likely not contributing to product formation. To investigate this possibility, we then conducted our biocatalytic reactions in the presence of amylase and lipase inhibitors (acarbose and orlistat, respectively;

Table 6). In the presence of excess inhibitor, the yield of the PPL reaction was essentially unchanged. Similarly, the yield of the reaction with the amylase component was only modestly reduced in the presence of excess inhibitor. We also confirmed that intrinsic lipase activity of the PPL preparation was fully inhibited in the presence of orlistat by monitoring hydrolytic activity with p-nitrophenylpalmitate with and without inhibitor (

Figure S2). Based upon these results, we conclude that lipase activity is not responsible for the promiscuous catalysis observed with crude preparations of PPL. Furthermore, while the reaction can be catalyzed by multiple proteinaceous entities regardless of whether they possess intrinsic enzymatic activity, not all proteins are capable of catalyzing product formation.

3. Discussion

In this study, we screened lipase preparations for catalysis of a one-pot Wieland–Miescher ketone synthesis. Our initial screen detected minimal product formation in the presence of lipases alone. As a result, we turned to literature conditions used in the L-Pro catalyzed WMK synthesis for reaction optimization purposes. We found that inclusion of a basic co-catalyst was essential for promoting higher yields of WMK in the presence of a protein catalyst, in contrast to the L-Pro catalyzed reaction, which requires no co-catalyst. In addition, we used proteomics to characterize the primary components of a crude lipase mixture that has been previously used in numerous studies of biocatalysis. We anticipate that these results will inform future studies using this catalytic preparation. After further optimizing catalyst loading and solvent conditions, we then re-screened a lipase library, correlating absorbance of the crude reaction mixture with production of WMK product. This approach could easily be expanded to screen larger libraries of potential biocatalysts. Finally, we demonstrated that the innate enzymatic activities of the proteins present are not required for product formation. While the identification of the essential catalytic moieties remains incomplete, it appears that future optimization work might best be focused on alternative considerations, such as shape complementarity and surface exposed sidechains, rather than the native catalytic mechanisms of these promiscuous biocatalysts. For example, the poorer enantioselectivity of protein biocatalysts versus the individual amino acid L-Pro is intriguing, suggesting that the presence of a well-defined active-site cavity contributes little to stabilization of the transition state. However, the advantages of a protein biocatalyst over an individual amino acid catalyst (more engineerable, more adaptable to immobilization, etc.) support future engineering efforts of these nascent catalytic entities. Furthermore, as not all lipase preparations tested in this screen supported promiscuous biocatalytic activity, there are protein preparation-dependent aspects of this biocatalytic synthesis that require further investigation.

Promiscuity in biocatalysis remains an intriguing topic, often challenging chemists to think outside the comfort zone of well-established catalytic mechanisms. In this work, we demonstrated that the assumptions regarding the role of intrinsic catalytic properties of promiscuous biocatalysts should be carefully considered. In many studies, catalytic promiscuity has undoubtedly been misattributed to various properties of one enzyme or another, when the role of surface exposed amino acids, protein shape, or even influence of the dielectric environment may be more important. For promiscuous biocatalysts to fulfill their potential as inexpensive and reusable “green” reagents, it is critical that their modes of action be more precisely characterized. For example, in this study, we identified alpha amylase as a key catalytic component of a crude lipase preparation from porcine pancreas. As a result, future studies can now be conducted on the optimization of this protein for promiscuous biocatalysis through rational design, directed evolution, or exploration of immobilization methodologies. Furthermore, this study established that colorimetric screening can be useful for identifying catalysts of WMK formation. In addition to this being a general platform for identifying new biocatalysts, we anticipate that this screen can be extended to other variations on the Robinson annulation, enabling screening for substrate scope.

4. Materials and Methods

Chemicals, substrates, and solvents were purchased from commercial sources (Millipore-Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); TCI America (Portland, OR, USA); VWR (Radnor, PA, USA); and Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Lipases, amylases, and carboxypeptidases were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (see

Table 7).

LC/MS mass spectrometry method. Liquid chromatography (LC) was performed on a HPLC system (3200 Exion LC100; SCIEX Corporation, Framingham, MA, USA). Five microliters of samples were injected into the reversed-phase Gemini NX-C18 column (50 mm × 2.0 mm, 3 µm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) by using auto sampler. The mobile phase composition for A was water/acetonitrile mixture (95/5, v/v) with 0.1% formic acid, and for B was methanol. The gradient method was as follows: 100% A for 1 min, decrease to 15% over 4 min, hold at 15% for 1 min, increase back to 100% over 1 min, and hold at 100% for 3 min. The flow rate was 0.3 mL min−1 and total run time was 10 min for each sample injection. The column temperature was kept at 35 °C. The LC elute was introduced into the Applied Biosystem Triple Quad API 3200, a triple-quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (Beverly, MA, USA) equipped with a turbo spray ionization source, for quantification of compounds in positive ionization mode. Detection of the target molecule was performed in a multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, and transition of m/z 179.24 to 161.20 was used for detection of WMK.

Biocatalysis general conditions. The following reagents/reactants were mixed in a microcentrifuge tube for synthesis of Wieland–Miescher ketone: solvent (900 µL), methyl vinyl ketone (19.8 µL), 2-methyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione (20 mg), deionized water (100 µL), and lipase (0–40 mg) or L-proline (6.4 mg), with or without imidazole (2.7 mg, 0.04 mmol). For reaction involving inhibitors, the biocatalyst was mixed with the inhibitor (5 mg) for 10 min at room temperature before adding the substrates and cocatalyst. After reaction assembly, capped microcentrifuge tubes were placed in a temperature-controlled shaker (New Brunswick Excella e24; 35 °C, 250 rpm) for 89 h.

Cofactor and cosolvent optimization. The following reagents/reactants were mixed in a microcentrifuge tube for synthesis of Wieland–Miescher ketone: alcohol solvent (900 µL), methyl vinyl ketone (19.8 µL), 2-methyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione (20 mg), deionized water (100 µL), lipase (L1, 30 mg), and cocatalyst (0.04 mmol). After reaction assembly, capped microcentrifuge tubes were placed in a temperature-controlled shaker (New Brunswick Excella e24; 35 °C, 250 rpm) for 89 h.

Lipase purification and proteomics. Solutions of porcine pancreatic lipase and wheat germ lipase were fractionated on a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column connected to an Akta FPLC (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, city, State Abbr. (if has), country). Protein fractions were characterized via SDS-PAGE gels stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain (ThermoFisher). The bands of greatest intensity were excised and digested with trypsin overnight using a standard in-gel digestion protocol. The resultant tryptic peptides were desalted using a C18 Zip-Tip and applied to a MALDI target plate with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix. The sample was analyzed on an AB Sciex 5800 MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Framingham, MA, USA). MS/MS spectra were searched against Uniprot databases using Mascot version 2.3 (Matrix Science) (Boston, MA, USA) within ProteinPilot software version 3.0 (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA). A significance score threshold was calculated in Mascot, with ion scores above the threshold considered positive IDs (p < 0.05).

Hi-Res Mass Spec analysis of triketone and WMK. Samples were analyzed with a Q Exactive HF-X (ThermoFisher, Bremen, Germany) mass spectrometer. Samples were introduced via a heated electrospray source (HESI) at a flow rate of 10 µL/min. One hundred times domain transients were averaged in the mass spectrum. HESI source conditions were set as: nebulizer temperature 100 deg C, sheath gas (nitrogen) 15 arb, auxiliary gas (nitrogen) 5 arb, sweep gas (nitrogen) 0 arb, capillary temperature 250 °C, RF voltage 100 V, and spray voltage 3.5 KV. The mass range was set to 150–2000 m/z. All measurements were recorded at a resolution setting of 120,000. Solutions were analyzed at 0.1 mg/mL or less based on responsiveness to the ESI mechanism. Xcalibur (ThermoFisher, Breman, Germany) was used to analyze the data. Molecular formula assignments were determined with Molecular Formula Calculator (v 1.2.3). All observed species were singly charged, as verified by unit m/z separation between mass spectral peaks corresponding to the 12C and 13C12Cc-1 isotope for each elemental composition.

Characterization of triketone (2-methyl-2-(3-oxobutyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione): Hi-Res mass spec: m/z = 197.11761 (mass error = 2.0 ppm) Assigned Chemical Formula: C11H17O3 [M+H]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 2.60–2.77 (m, 4H), 2.35 (t, 2H), 2.11 (s, 3H), 2.04–2.08 (m, 2H), 1.89–1.95 (m, 2H), 1.25 (s, 3H).

Characterization of WMK ((S,R)-(+/−)-8a-methyl-3,4,8,8a-tetrahydro-1,6(2H,7H)-naphthalenedione): Hi-Res mass spec: m/z = 179.10583 (mass error = −4.6 ppm) Assigned Chemical Formula: C11H15O2 [M+H]+; 1H NMR (400 MHz): 5.85 (s, 1H), 2.67–2.76 (m, 2H), 2.38–2.52 (m, 4H), 2.09–2.19 (m, 3H), 1.65–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.45 (s, 3H).

HPLC analysis of reaction yield. Liquid chromatography was performed on a HPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) consisting of a binary pump (1525 Binary HPLC Pump), absorbance detector (2487 Dual Wavelength Absorbance Detector), and auto sampler (717-plus Autosampler). Five microliters of sample were injected into the reversed-phase Xterra MS C18 column (4.6 mm × 100 mm, 5 µm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) using the auto sampler. The samples were analyzed using an isocratic method: 80% Solvent A (water) and 20% Solvent B (methanol). The flow rate was 1.0 mL min−1 and the total run time was 13 min for each sample injection. The detector wavelength was set to 210 nm and the retention time for WMK was 7.9 min.

HPLC analysis of enantiomeric excess. Liquid chromatography for enantiomeric excess was performed on a HPLC system (Waters Corporation) consisting of binary pump (1525 Binary HPLC Pump), absorbance detector (2487 Dual Wavelength Absorbance Detector), and auto sampler (717-plus Autosampler). Five microliters of sample were injected into the Chiralcel OD-H column (0.46 cm × 25 cm; Daicel, Minato, Japan) using the auto sampler. Isopropanol/heptane mixture (20/80, v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid was used as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.1 mL min−1. Total run time was 111 min for each sample injection. The detector wavelength was set to 250 nm and the retention times for (S)-WMK and (R)-WMK were 43.5 and 46.3 min, respectively.