2.1. Theoretical Prediction

DFT method was used to calculate the HBE and OHBE values on (111), (200), and (220) facets of Ni

3TM

1 alloys. The HBE and OHBE values are presented in

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4,

Table A5 and

Table A6 (

Appendix A). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the OHBE values were calculated for the electrocatalysts.

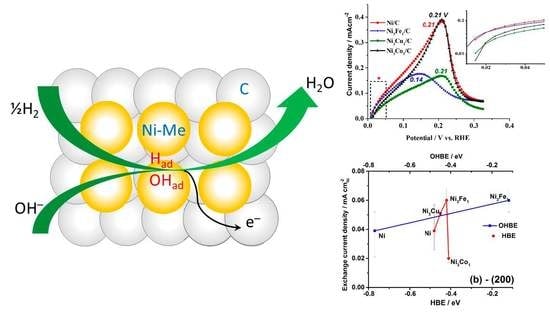

Figure 1 shows the calculated HBE values (

Figure 1a) and OHBE values (

Figure 1b) for the case of pure Ni and different Ni

3TM

1 alloys. As seen in

Figure 1 and

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3 (

Appendix A), hydrogen atom has the lowest HBE for the (111) facet, compared to the (220) and (200) facets. For example, HBE value for bare Ni (111) is −0.54 eV, while is −0.48 and −0.45 eV for Ni (200) and Ni (220), respectively (see also

Tables S1–S3, Supplementary Materials). The reason for the stability of the (111) facet is that H atoms can establish more bonds on the (111) facet, which is more atomically dense than other facets. The facet Ni (200) of the bare Ni shows the highest affinity to OH chemisorption and the facet (220) is characterized by the weakest OH bonding (OHBE: (200) ˂˂ (111) < (220)) (

Figure 1b). The comparison of OHBE and HBE values (HBE and OHBE are −0.54 eV for (111), and HBE is −0.45 and OHBE is −0.49 eV for (220)) shows that the co-adsorption of the both H and OH species is thermodynamically favorable.

Some authors assume that the kinetics of HOR directly follows the thermodynamics of the reaction [

39,

40], and therefore it is explicitly related to the HBE values according to the so-called volcano plot [

41], where HOR/HER exchange current densities are plotted versus HBE, with the PGMs normally at the top of the graph. The optimal HBE value was predicted to be ca. −0.24 eV, which corresponds to the HOR ΔG~0 [

41]. HBE might be considered as the main factor influencing the HOR kinetics solely in case the rate-determining step (rds) of the reaction is either Volmer [

42], or Heyrovsky reactions [

43], namely the removal of the adsorbed H atom from the catalyst surface. Studies of the HOR mechanism in alkaline for Pt electrocatalysts have revealed a controversy in the experimental data interpretation [

22]: while some of the authors experimentally proved that Tafel reaction is the HOR rds [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], others provided experimental evidence for the HOR kinetics limited by the Volmer reaction [

49,

50].

The mechanism of HOR on Ni-based materials has been hardly explored [

22,

51]. The analysis below is done provided that Volmer or Heyrosky reactions are rds of HOR in alkaline media—the speculative assumption based on the nonlinear dependence of the HOR kinetics on the surface coverage [

34,

52]. The HBE value calculated for the facet Ni (111), −0.54 eV (

Figure 1), is more negative than those calculated for Pt (111), Rh (111) and Ir (111), −0.37, −0.33 and −0.24 eV [

30], respectively. In turn, Pt, Rh and Ir show the highest catalytic activity in HOR in alkaline media, which is more than two orders of magnitude higher than that of Ni electrocatalysts [

22]. Thus, based on the predicted optimal HBE value [

41] and on the calculated HBE values for the most active catalytic materials [

22], the recommended HBE values for the newly designed electrocatalysts should fall into the range between ca. −0.33 to −0.24 eV. In case of Ni-based materials, higher catalytic activity would be expected at the HBE values which are less negative than those for the bare Ni surfaces.

Among the facets, Pt (100) surpasses the activity of (110) by an order of magnitude, while (111) shows the lowest activity: (110) ≫ (100) > (111) [

44,

53]. This sequence could be correlated with the HBE values estimated from the peak potential values for the desorption of the underpotentially deposited hydrogen atom in 0.1 M KOH: −0.48 eV for Pt (110) is much less negative compared to −0.60 eV for Pt (100) [

39,

49]. The exchange current density values,

i0, of carbon supported polycrystalline Pt nanoparticles, Pt/C, and bulk polycrystalline Pt, Pt(pc), are close to each other [

54,

55] and to

i0 for Pt (110) [

44]. Thus, the catalytic activity in HOR might be mainly determined by the presence of the facet Pt (110). The calculations of the HBE values done for Pt(pc) show a span within the range of −0.46 [

29] and −0.33 [

41] eV, while the value of −0.48 eV is reported for Pt/C [

56]. Similar order of activity (Ni (110) > Ni (100) > Ni (111)) is observed in the study of Floner et al. [

51]: Ni (100) and above all (110) are more active than polycrystalline Ni, whereas the behavior of the latter is close to (111), particularly at low pH where dissolution of Ni occurs. Based on the results of Floner et al. [

51], we assume that

i0 of the polycrystalline Ni

3TM

1/C electrocatalysts might be dominated by the facet Ni (110) or Ni (220). Interestingly, our calculated HBE values for the bare Ni facets is mostly ordered according to Ni (220) > Ni (200) > Ni (111) (see

Figure 1), in good agreement with the activity order experimentally shown by Floner et al. [

51]. Furthermore, as seen in

Figure 1, it follows that solely alloying Ni with Co results in a positive shift of the HBE value compared to the bare Ni (111) facet, −0.45 vs. −0.54 eV. For the facet (200), the alloying with Sc, Cr, Fe, Co, Cu and Zn were shown to have a positive effect on the HBE values, with only Ni

3Zn

1 (−0.19 eV) close to the aimed range of −0.33–−0.24 eV. Ni

3Fe

1, Ni

3Co

1 and Ni

3Cu

1 demonstrate the HBE values close to the earlier reported Ni

3Ag

1 [

36], CoNi/Mo (110) [

29], and Ni/N-CNT [

28], the last two materials showing the highest mass specific/surface specific activity values published till now. As regarding the facet (220), the HBE value of Ni

3V

1 falls into the recommended range, and the catalyst might be of interest of the HOR. Ni

3Fe

1 (−0.37 eV) and Ni

3Co

1 (−0.35 eV) of the facet (220) could also result in better HOR than bare Ni catalyst, and therefore, they are included in our experimental work for further study. Thus, based on the theoretical predictions (

Figure 1), a series of carbon supported binary electrocatalysts (Ni

3Fe

1, Ni

3Co

1 and Ni

3Cu

1) and monometallic Ni (as reference material) were synthesized by the chemical reduction method. Fe, Co and Cu were chosen as the TM dopants due to their promising HBE and OHBE values (

Table A4,

Table A5 and

Table A6,

Appendix A).

2.2. Physical and Chemical Characterization

The TEM image (

Figure S1a, Supplementary Materials) shows that electrocatalysts are characterized by nanoscopically uniform distribution of near-spherical particles with the average diameter of ca. 10 nm (

Figure S1b, Supplementary Materials), surrounded by amorphous carbon support. Assuming spherical particles, the calculated specific surface area of ca. 70 m

2g

−1Ni would be expected for a particle average diameter of 10 nm.

For binary Ni

3TM

1/C catalysts, element mapping revealed nanoscopically non-homogeneous co-distribution of the metallic components (

Figures S2–S4, Supplementary Materials). This shows that the chemical reduction method most likely might result in the formation of composite materials (mechanical mixtures), rather than alloys. The most significant heterogeneity was observed for the Ni

3Cu

1/C catalyst (

Figure S4, Supplementary Materials), where separate areas of Ni (red pixels) and Cu (green pixels) can be seen. Surface enrichment by Ni phase (red pixels) was revealed for all the binary Ni

3TM

1/C systems (

Figures S2–S4, Supplementary Materials), which is in good agreement with the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) data (

Table S1, Supplementary Materials). The opposite—bulk segregation of Ni—was observed in binary Ni

9Mo

1/C electrocatalyst [

34]. These observations illustrate that special controlled synthetic approaches are needed in order to synthesize Ni-TM materials with the given Ni-to-TM ratio. Nevertheless, quite homogeneous metal co-distribution topography was observed for the Ni-Fe and Ni-Co couples in Ni

3Fe

1/C (

Figure S2, Supplementary Materials) and Ni

3Co

1/C (

Figure S3, Supplementary Materials) catalyst, respectively. This latter observation might be related to the fact that Ni co-deposits simultaneously with Co and Fe due to the reduction potential values. To compare, the standard reduction potentials of Ni (

and Co (

are close, whereas Cu has much higher potential (

. Consequently, the coexistence of the composites with the alloyed phase(s) in Ni

3TM

1/C catalysts cannot be ruled out unambiguously. Therefore, a thorough analysis of the XRD patterns of the as-synthesized catalysts and of those after the thermal treatment at 450 °C was done (

Figures S5 and S6, Supplementary Materials). On XRD patterns (

Figure S5), catalysts show wide peaks at ~44.5° of low intensity, which corresponds to Ni (111) facets, the same facet as calculated by DFT (see previous section). Small particle sizes explain the broadening of the (111) peak (with extremely low crystallite sizes of ca. 0.7 nm) and the absence of (200) and (220) reflections on the XRD patterns, which does not rule out the coexistence of the high-index facets in the catalysts. The Ni (200) and Ni (220) facets are expected to appear at 51.85° and 76.37°, respectively. All the catalysts are characterized by the presence of hydrated nickel hydroxide Ni(OH)

2·0.75H

2O (ICDD, #00-038-0715) or nickel oxyhydroxide Ni

5O(OH)

9 (ICDD, #00-027-0340) phase. These phases can be ascribed to the surface oxidation of the catalysts, which potentially may block the electrochemically active surface (see the section below). According to the XPS analysis (

Figure S8, Supplementary Materials), the surface of Ni is predominantly oxidized to NiO, Ni

2O

3 and Ni(OH)

2 with the ratio of metallic Ni between 4.5 to 18 at.% (

Table S3, Supplementary Materials). Copper phase in Ni

3Cu

1/C is partially oxidized forming Cu

2O (ICDD, #00-005-0667), which is in an agreement with the XPS data (

Figure S7a, Supplementary Materials). The crystallite sizes of metallic copper are ca. 22 nm, which is comparable to the catalyst particle sizes (

Figure S1, Supplementary Materials). Shale-up satellites of copper for Ni

3Cu

1/C catalyst (

Figure S7a, Supplementary Materials) are characteristic of divalent Cu, whereas monovalent Cu has no satellites [

57]. The peak at 953.0 can correspond to all three components: Zerovalent Cu (Cu 2p

1/2 at 952.6 eV) [

58], monovalent (Cu 2p

1/2 at 952.7 eV) [

59] or divalent Cu (Cu 2p

1/2 at 952.5 eV) [

60], as well as the peak at ca. 933 eV. High resolution XPS spectrum for Ni

3Fe

1/C (

Figure S7b,

Supplementary Materials) shows three distinguishable peaks: A peak of the highest intensity at binding energy (BE) ~712–714 eV which could be ascribed to Fe

3+ salts, but most probably arises from Ni LMM Auger peak (712 eV), overlapping with Fe 2p

3/2. The peak of low intensity at 707.9 eV corresponds to metallic Fe [

61]. The broad peak at ca. 725 eV can be ascribed to either Fe

2O

3 (Fe 2p

1/2 at 724 eV) [

62], or FeOOH (Fe 2p

1/2 at 724.3 eV) [

62], or Fe

3O

4 (Fe 2p

1/2 at 723.5 eV) [

62]. It is more challenging to determine the concentration and chemical shifts of cobalt for Ni

3Co

1/C, since Co 2p

3/2 is close to Ni LMM structure and Co 3p spectrum overlaps with the one for Ni 3p.

The XRD patterns registered on the as-synthesized Ni

3TM

1/C catalysts cannot provide clear evidence of metal alloying. Therefore, thermal treatment at 450 °C in reducing atmosphere was used as an indirect indication of the presence of several metallic phases in the as-synthesized materials. The XRD patterns deconvolution for the heat-treated Ni

3Fe

1/C (

Figure S6d,

Supplementary Materials) and Ni

3Cu

1/C (

Figure S6c,

Supplementary Materials) have shown a splitting of the reflections into two peaks. One of them can be ascribed to the alloy phases enriched by Ni and by the other—to the second transition metal. For instance, the reflections of Ni

3Cu

1/C at the 2θangles of 44.16, 51.45 and 75.92 are close to those for the alloy Ni

3Cu

1 (ICDD, #04-004-4502), whereas the set of the facets at 43.96, 51.41 and 75.68 is shifted to the metallic Cu (ICDD, #00-004-0836) and may correspond to the Cu-rich Ni-Cu alloys.

Thus, chemical reduction of the inorganic precursors on carbon support using sodium borohydride as the reducing agent results in the formation of near-spherical nanoparticles with poor crystallinity and the average particle size of ca. 10 nm. In the binary Ni3TM1/C catalysts, heterogeneous co-distribution the metallic components was observed, with partially separated areas of Cu2O in Ni3Cu1, and segregation of Ni on the surface for all the samples. Homogeneity of the metallic components co-distribution in the bulk of the as-synthesized catalysts and the separation of the XRD reflexes after the thermal treatment at 450 °C illustrates that the binary Ni3TM1/C catalysts are predominantly composites—mechanical mixtures of either Ni with TM, or mixture of several NixTMy alloys.

2.3. Electrochemical Characterization

Figure 2a shows the first several cycles of the HOR polarization curves (solid lines) on the Ni/C catalyst and compares them with the corresponding cyclic voltammogram recorded in Ar atmosphere (dashed line). Opposed to the behavior of the TM-doped catalysts, bare Ni shows a significant increase of the catalytic activity after the first HOR cycle (

Figure 2a), namely after the partial electrochemical oxidation of the surface. The positive effect of the surface pre-oxidation on the Ni catalytic activity in HOR was also reported previously [

52,

63]. This observation might serve as direct experimental evidence of the bifunctional mechanism of HOR [

26,

50,

64,

65,

66,

67] when OH

ad species, pre-chemisorbed on the adjacent active sites, are required in order to remove H

ad chemisorbed on the free metallic surface of Ni, and to make the hydrogen oxidation reaction proceed. Thus, presumably a certain optimal ratio of Ni(OH

ad)/Ni(H

ad) sites is needed to retain the HOR activity of bare Ni electrocatalyst. Therefore, the theoretical estimations of HBE and OHBE, provided in

Figure 1a,b, might shed some light on the understanding of the competitive co-adsorption of H and OH species (see

Section 2.1). Noteworthy, Ni

3TM

1 catalysts do not require a preliminary electrooxidation cycle, which might be related either to the fact that the presence of TMs with higher affinity to oxygen (such as Cu [

68], Co [

69] and Fe [

69]) stabilizes the oxygenated species on the surface of Ni, or the TMs serve by themselves as the active sites for formation of OH

ad species. In any case, an important theoretical question arises: Would a hypothetical surface with the optimal value of HBE (discussed earlier) and no affinity to chemisorption of OH species catalyze HOR in alkaline media? Might it be the case that PGMs (e.g., Pt, Ir, Rh) show two orders of magnitude lower catalytic activity in HOR in alkaline media compared to acidic ones [

45,

49,

56], because in the potential range of hydrogen electrooxidation the surfaces produce a negligibly low ratio PGM(H

ad)/PGM(OH

ad)? The doping of PGMs by TMs with high affinity to chemisorption of OH species was shown to result in the HOR catalysis promotion [

67,

70,

71]. However, this subject is beyond the scope of this work.

HOR polarization curves in the potential range of 0–0.4 V, presented in

Figure 3a,b, show electrocatalytic behavior of Ni/C, Ni

3Fe

1/C, Ni

3Co

1/C and Ni

3Cu

1/C typical for polycrystalline Ni [

51], or TM doped Ni electrocatalysts [

34]. For all the catalysts, during the forward scan (

Figure 2a,b), a peak of HOR is observed, with the current increasing up to certain potential values (see the peak potential values in

Figure 2b). Further, the surface deactivates with the increase of the potential due to the increasing surface electrooxidation, and at

E > 0.4 V there is no catalytic activity in HOR. A similar effect was observed in HOR for Ru/C [

72] due to the competitive adsorption of H

2 and OH

−. On the backward scan, the surface of the catalysts reactivates, due to the reversible electrochemical reduction of Ni (see black solid and dashed circles marking the onset of HOR and Ni electroreduction, respectively, on the backward scans).

The analysis of the HOR kinetics in the micropolarization area (0.01–0.05 V) reveals a clear effect of the dopant on the exchange current density: At the comparable values of the electrochemical surface area (ECSA), bare Ni/C shows 0.039 mA cm

−2Ni (

Table 1), whereas addition of Fe, for instance, results in a significant reaction promotion with 0.06 mA cm

−2Ni, which in turn positively affects mass specific activity, 1.6 A g

−1Ni vs. 1.87 g

−1Ni (

Table 1). The

i0 values reported in this work exceed the highest

i0 values reported earlier in the literature, for instance, 0.028 mA cm

−2Ni for hydrothermally synthesized 70% Ni/N-CNT [

28], or 0.027mA cm

−2Ni for thermally reduced 50% Ni

9Mo

1/C [

34] and 0.025 mA cm

−2Ni for 50% Ni

9.5Cu

0.5/C [

73], showing that chemical reduction might be a promising approach for the further development of Ni-based catalysts. However, overall catalyst mass activity of our catalysts is lower (0.35–0.55 A g

−1cat) for the binary electrocatalysts compared to the bare Ni/C (0.6 A g

−1cat), due to the high concentration of the catalytically inert TMs. The mass catalytic values are lower (6.5 A g

−1cat for 70%Ni/N-CNT [

28], 3.54 A g

−1cat for the electrodeposited CoNiMo [

29], 2.9 A g

−1cat for 50% Ni

9Mo

1/C [

34]) or comparable (0.94 A g

−1cat for 25% Ni

9.5Cu

0.5/Vulcan XC72 [

37]) to the published ones. In previous works, the authors have applied preliminary electrochemical reduction of the surface, which allowed increasing the surface area up to 10–20 m

2 g

−1Ni. In our work, we have intentionally avoided the preliminary reduction step in order to demonstrate that carbon supported nanoparticles synthesized via simple chemical reduction method at ~0 °C can be handled in ambient atmosphere, and they can still retain their electrocatalytic activity, opposed, for instance, to the thermally obtained Ni-based electrocatalysts [

34].

Figure 3a–d shows the linear potential stripping (solid lines) for the catalysts under Ar atmosphere at the same potential sweep rate (1 mV s

−1) used to record the HOR polarization curves, and the corresponding derivatives of the HOR polarization curves (dashed lines), for all the catalysts. The charge consumed for the full surface coverage by Ni(OH)

2 (the area under the solid line peaks,) was used to estimate ECSA of Ni. The ECSA values are presented in

Table 1. Extremely low ECSA values were obtained in all catalysts (< 2 m

2 g

−1Ni compared to the expected ~ 70 m

2 g

−1Ni based on TEM images,

Figure S1, Supplementary Materials), which are probably due to the oxidative surface passivation evidenced by EDS (

Table S1, Supplementary Materials) and XPS (

Tables S1 and S3, Figure S8, Supplementary Materials).

The HOR polarization curves (

Figure 2b) were differentiated, and the potential values corresponding to the minimum of the derivatives (dashed lines,

Figure 3a–d) were used as one of the catalyst characteristic parameters, showing the potential of the catalytic activity loss. As seen from

Figure 3a–d, the potentials of the derivative minimum (marked in red: 0.23, 0.23, 0.20 and 0.24 V for on the bare Ni/C, Ni

3Co

1/C, Ni

3Fe

1/C, and Ni

3Cu

1/C, respectively) correspond to the full surface coverage (indicated by black arrows). Full surface coverage by monolayer of Ni(OH)

2 on the bare Ni/C, Ni

3Co

1/C and Ni

3Cu

1/C takes place at more anodic potential (0.23, 0.23 and 0.24 V, respectively,

Figure 3a,b,d), whereas the surface of Ni

3Fe

1/C is fully covered already at 0.20 V (

Figure 3c). The peak potential of Ni

3Fe

1/C electrooxidation (solid line,

Figure 3c), 0.125 V, is negatively shifted as well compared to Ni/C (

Figure 3a), Ni

3Co

1/C (

Figure 3b) and Ni

3Cu

1/C (

Figure 4d). Thus, Ni-Fe catalysts are prone to the higher OH

ad coverage at lower overpotentials, which results in higher HOR catalytic activity at lower overpotential values (

Figure 3b, insert).

Figure 4a shows the general trend of decrease in exchange current density values with the HBE value increase for the facet (111), whereas the opposite trend is expected (see

Section 2.1. Theoretical prediction). At the same time, the expected catalytic activity increase is observed with the increase of HBE for the facets (200) and (220) (

Figure 4b,c). This observation might indicate that the catalytic activity is predominantly determined by higher index surfaces, (200) and (220).

Figure 5a,b also show that

io increases as OHBE values increase. The latter observation might serve as indirect evidence of the bifunctional mechanism of the HOR hypothesized earlier in different studies [

25,

26,

64] explaining the promotion effect of the dopants on the HOR kinetics. According to this bifunctional mechanism, there is a need for more than the conventional HBE indicator to describe the HOR in alkaline [

22]—the OHBE indicator may bring the missing parameter to clearly understand the HOR kinetics and mechanism.

This study provides an initial thought supported with some first data on HBE and OHBE, both as important parameters to describe the electrocatalytical activity of Ni-based catalysts towards HOR in alkaline medium. Further DFT calculations and experimental studies of specifically Ni-TM facets are needed to increase this understanding.