Improving Photovoltaic Properties of P3HT:IC60BA through the Incorporation of Small Molecules

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of the BHJ PSCs

2.3. Measurements and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optical, Structural and Morphological Properties

3.2. Photovoltaic Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, L.; Zheng, T.; Wu, Q.; Schneider, A.M.; Zhao, D.; Yu, L. Recent advances in bulk heterojunction polymer solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12666–12731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, S.; Ngo, E.; Khatiwada, D.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, Q. Enhanced lifetime of polymer solar cells by surface passivation of metal oxide buffer layers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 16093–16100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y. Polymer solar cells. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yi, C.; Wang, K.; Yang, Y.; Bhatta, R.S.; Tsige, M.; Xiao, S.; Gong, X. Single-junction polymer solar cells with over 10% efficiency by a novel two-dimensional donor-acceptor conjugated copolymer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 4928–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Chen, H.-Y.; Hou, J.; Li, Y. Indene-C60 bisadduct: A new acceptor for high-performance polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loew, N.; Komatsu, S.; Akita, H.; Funayama, K.; Yuge, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Ihara, M. TiO2 as electron-extraction-layer in reverse type P3HT/ICBA organic solar cells. ECS Trans. 2014, 58, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, A.; Gojanović, J.; Matavulj, P.; Islam, M.; Živanović, S. Temperature dependence of P3HT: ICBA polymer solar cells. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Numerical Simulation of Optoelectronic Devices (NUSOD), Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–28 July 2017; pp. 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan, S.-A.; Gopalan, A.-I.; Vinu, A.; Lee, K.-P.; Kang, S.-W. A new optical-electrical integrated buffer layer design based on gold nanoparticles tethered thiol containing sulfonated polyaniline towards enhancement of solar cell performance. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 174, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Fang, G.; Fan, X.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Q.; Qin, P.; Lei, H.; Li, Y. Enhancing the performance of P3HT:ICBA based polymer solar cells using LIF as electron collecting buffer layer and UV–ozone treated MoO3 as hole collecting buffer layer. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 110, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Chen, J.; Ngo, E.C.; Dubey, A.; Khatiwada, D.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, Q. Critical role of domain crystallinity, domain purity and domain interface sharpness for reduced bimolecular recombination in polymer solar cells. Nano Energy 2015, 12, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemnes, G.A.; Iftimie, S.; Palici, A.; Nicolaev, A.; Mitran, T.L.; Radu, A.; Antohe, S. Optimization of the structural configuration of ICBA/P3HT photovoltaic cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 424, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, J.; Soci, C.; Coffin, R.C.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Mikhailovsky, A.; Moses, D.; Bazan, G.C. Method for increasing the photoconductive response in conjugated polymer/fullerene composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 252105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, I.E.; Wang, F.; Bedolla Valdez, Z.I.; Ayala Oviedo, A.N.; Bilsky, D.J.; Moule, A.J. Photoinduced degradation from trace 1,8-diiodooctane in organic photovoltaics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Lee, Y.; Lin, Y.-H.; Strzalka, J.; Wang, C.; Hexemer, A.; Jaye, C.; Fischer, D.A.; Verduzco, R.; Wang, Q.; et al. Photovoltaic performance of block copolymer devices is independent of the crystalline texture in the active layer. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 4599–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hou, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, G.; Yang, Y. Effects of solvent mixtures on the nanoscale phase separation in polymer solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 1783–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, M.; Ma, W.; Zhang, S.; Hou, J.; Li, Y. Effect of solvent additive on active layer morphologies and photovoltaic performance of polymer solar cells based on PBDTTT-C-T/PC71BM. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 51924–51931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkin, A.; Ritter, U.; Scharff, P.; Schrödner, M.; Sensfuss, S.; Aganov, A.; Klochkov, V.; Ecke, G. Improvement of P3HT–ICBA solar cell photovoltaic characteristics due to the incorporation of the maleic anhydride additive: P3HT morphology study of P3HT–ICBA and P3HT–ICBA–MA films by means of X-band LESR. Synth. Met. 2014, 197, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lim, E. Development of polymer acceptors for organic photovoltaic cells. Polymers 2014, 6, 382–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, S.-A.; Seo, M.-H.; Anantha-Iyengar, G.; Han, B.; Lee, S.-W.; Kwon, D.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, S.-W. Mild wetting poor solvent induced hydrogen bonding interactions for improved performance in bulk heterojunction solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Bai, Y.; Bian, X.; Zhang, B.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Tan, Z.A. The effect of donor and nonfullerene acceptor inhomogeneous distribution within the photoactive layer on the performance of polymer solar cells with different device structures. Polymers 2017, 9, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.H.T.; Truong, N.T.N.; Trinh, T.K.; Lee, S.H.; Park, C. Controlling the morphology of the active layer by using additives and its effect on bulk hetero-junction solar cell performance. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lu, K.; Xia, B.; Fang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wei, Z.; Jiang, L. Improving the performances of random copolymer based organic solar cells by adjusting the film features of active layers using mixed solvents. Polymers 2016, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, T.; Khoram, P.; Min, J.; Brabec, C.J. Organic ternary solar cells: A review. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4245–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Xu, T.; Chen, W.; Landry, E.S.; Yu, L. Ternary blend polymer solar cells with enhanced power conversion efficiency. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianakis, M.M.; Konios, D.; Viskadouros, G.; Vernardou, D.; Katsarakis, N.; Koudoumas, E.; Anastasiadis, S.H.; Stratakis, E.; Kymakis, E. Ternary organic solar cells incorporating zinc phthalocyanine with improved performance exceeding 8.5%. Dyes Pigments 2017, 146, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, U.; Bahrami, B.; Biesecker, M.; Baroughi, M.F.; Qiao, Q. Kinetic Monte Carlo modeling on organic solar cells: Domain size, donor-acceptor ratio and thickness. Nano Energy 2017, 35, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitul, A.F.; Mohammad, L.; Venkatesan, S.; Adhikari, N.; Sigdel, S.; Wang, Q.; Dubey, A.; Khatiwada, D.; Qiao, Q. Low temperature efficient interconnecting layer for tandem polymer solar cells. Nano Energy 2015, 11, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Kelly, M.A.; You, W.; Yu, L. Status and prospects for ternary organic photovoltaics. Nat. Photonics 2015, 9, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Gopalan, S.-A.; Gopalan, A.-I.; Muthuchamy, N.; Lee, K.-P.; Lee, J.-S.; Jiang, Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, J.-S.; et al. Functional solid additive modified PEDOT:PSS as an anode buffer layer for enhanced photovoltaic performance and stability in polymer solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Chen, W.; Xu, T.; Yu, L. High-performance ternary blend polymer solar cells involving both energy transfer and hole relay processes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minas, M.S.; Dimitrios, K.; Constantinos, P.; George, K.; Emmanuel, S.; Emmanuel, K. Ternary solution-processed organic solar cells incorporating 2D materials. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 042005. [Google Scholar]

- Sai-Anand, G.; Han, B.; Kang, B.-H.; Kim, S.-W.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, J.-S.; Jeong, H.-M.; Kang, S.-W. Incorporation of gold nanodots into poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) for an efficient anode interfacial layer for improved plasmonic organic photovoltaics. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 7092–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.; Shrotriya, V.; Yang, G.; Yang, Y. “Solvent annealing” effect in polymer solar cells based on poly(3-hexylthiophene) and methanofullerenes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 1636–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, F.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Nordlund, D.; Wu, H.; Russell, T.P.; Cao, Y. Simultaneous spin-coating and solvent annealing: Manipulating the active layer morphology to a power conversion efficiency of 9.6% in polymer solar cells. Mater. Horiz. 2015, 2, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Bilen, C.; Feron, K.; Zhou, X.; Belcher, W.J.; Dastoor, P.C. Enhanced regeneration of degraded polymer solar cells by thermal annealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 193905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, F.; Tassinari, F.; Libertini, E.; Lanzi, M.; Mucci, A. Π-stacking signature in NMR solution spectra of thiophene-based conjugated polymers. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 5775–5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai-Anand, G.; Gopalan, A.-I.; Lee, K.-P.; Venkatesan, S.; Kang, B.-H.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, J.-S.; Qiao, Q.; Kwon, D.-H.; Kang, S.-W. A futuristic strategy to influence the solar cell performance using fixed and mobile dopants incorporated sulfonated polyaniline based buffer layer. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 141, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinelli, F.; Costa-Bizzarri, P.; Della-Casa, C.; Lanzi, M. Analysis of UV–Vis spectral profiles of solvatochromic poly[3-(10-hydroxydecyl)-2,5-thienylene]. Spectrochim. Acta A 2002, 58, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllerová, J.; Kaiser, M.; Nádaždy, V.; Šiffalovič, P.; Majková, E. Optical absorption study of P3HT:PCBM blend photo-oxidation for bulk heterojunction solar cells. Sol. Energy 2016, 134, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai-Anand, G.; Gopalan, A.-I.; Lee, K.-P.; Venkatesan, S.; Qiao, Q.; Kang, B.-H.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, J.-S.; Kang, S.-W. Electrostatic nanoassembly of contact interfacial layer for enhanced photovoltaic performance in polymer solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 153, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadem, B.; Hassan, A. The effect of fullerene derivatives ratio on P3HT-based organic solar cells. Energy Procedia 2015, 74, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Djukic, B.; Shi, W.; Bridges, C.R.; Kozycz, L.M.; Seferos, D.S. Evolution of the electron mobility in polymer solar cells with different fullerene acceptors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 8038–8043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Bao, Y.; Du, J.; Jiang, C.; Qiao, Q. Understanding of morphology evolution in local aggregates and neighboring regions for organic photovoltaics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 10168–10177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, H.-C.; Chen, P.-H.; Chang, R.; Su, W.-F. Morphological control agent in ternary blend bulk heterojunction solar cells. Polymers 2014, 6, 2784–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Ma, B.; Donuru, V.R.; Liu, H.; Frechet, J.M.J. Bodipy-backboned polymers as electron donor in bulk heterojunction solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4148–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclerc, N.; Chávez, P.; Ibraikulov, O.; Heiser, T.; Lévêque, P. Impact of backbone fluorination on π-conjugated polymers in organic photovoltaic devices: A review. Polymers 2016, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Chen, N.; Liu, G.; Wan, Y.; Perea, J.D.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, B.; Li, N.; Li, X.; et al. Towards a full understanding of regioisomer effects of indene-C60 bisadduct acceptors in bulk heterojunction polymer solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 10206–10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-H.; Cho, C.-H.; Kang, H.; Yu, H.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, B.J. Molecular structure-device performance relationship in polymer solar cells based on indene-C60 bis-adduct derivatives. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Zhu, X.; Liang, Y.; Guo, X. Interfacial layer engineering for performance enhancement in polymer solar cells. Polymers 2015, 7, 333–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Fu, G. Enhancing the efficiency of polymer solar cells by modifying buffer layer with N,N-dimethylacetamide. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Dubey, A.; Reza, K.M.; Adhikari, N.; Qiao, Q.; Bommisetty, V. Origin of photogenerated carrier recombination at the metal-active layer interface in polymer solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 27690–27697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solanki, A.; Wu, B.; Salim, T.; Lam, Y.M.; Sum, T.C. Correlation between blend morphology and recombination dynamics in additive-added P3HT:PCBM solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 26111–26120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.-H.; Hsiao, Y.-S.; Richard, E.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, P.; Li, G.; Chu, C.-W.; Yang, Y. The investigation of donor-acceptor compatibility in bulk-heterojunction polymer systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 043304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiow, C.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Lin, Y.-H.; Raja, R.; Rwei, S.-P.; Chiu, W.-Y.; Dai, C.-A.; Wang, L. Synthesis and characterization of two-dimensional conjugated polymers incorporating electron-deficient moieties for application in organic photovoltaics. Polymers 2016, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kaap, N.J.; Koster, L.J.A. Charge carrier thermalization in organic diodes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Gopalan, S.-A.; Lee, K.-D.; Kang, B.-H.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, J.-S.; Kwon, D.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kang, S.-W. Preheated solvent exposure on P3HT:PCBM thin film: A facile strategy to enhance performance in bulk heterojunction photovoltaic cells. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2014, 14, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Guo, W.; Zhang, L.; Long, Y.; Ruan, S. Improving the charge carrier transport of organic solar cells by incorporating a deep energy level molecule. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

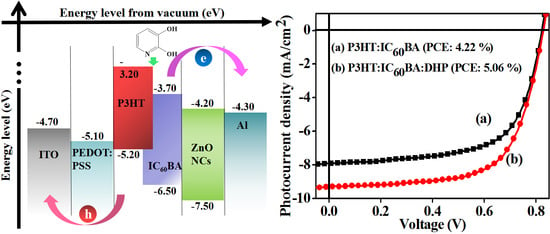

| BHJ PSC | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Rs (Ω) | FF | PCEE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3HT:IC60BA | 0.83 ± 0.013 | 8.36 ± 0.32 | 160 ± 23.98 | 0.63 ± 0.020 | 4.22 ± 0.13 |

| P3HT:IC60BA:DHP | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 9.39 ± 0.09 | 129 ± 4.04 | 0.66 ± 0.006 | 5.06 ± 0.05 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, B.; Sai-Anand, G.; Gopalan, A.-I.; Qiao, Q.; Kang, S.-W. Improving Photovoltaic Properties of P3HT:IC60BA through the Incorporation of Small Molecules. Polymers 2018, 10, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10020121

Xu B, Sai-Anand G, Gopalan A-I, Qiao Q, Kang S-W. Improving Photovoltaic Properties of P3HT:IC60BA through the Incorporation of Small Molecules. Polymers. 2018; 10(2):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10020121

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Binrui, Gopalan Sai-Anand, Anantha-Iyengar Gopalan, Qiquan Qiao, and Shin-Won Kang. 2018. "Improving Photovoltaic Properties of P3HT:IC60BA through the Incorporation of Small Molecules" Polymers 10, no. 2: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10020121

APA StyleXu, B., Sai-Anand, G., Gopalan, A. -I., Qiao, Q., & Kang, S. -W. (2018). Improving Photovoltaic Properties of P3HT:IC60BA through the Incorporation of Small Molecules. Polymers, 10(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10020121