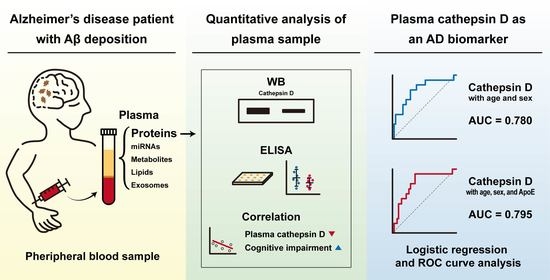

Identification of Cathepsin D as a Plasma Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Study Approval

2.2. Plasma Sample Preparation and Immunoblotting

2.3. Antibody Validation

2.4. ELISA

2.5. APOE Genotyping

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of Patient Plasma Samples for SDS-PAGE Analysis

3.2. The Level of Cathepsin D Decreases in the AD Patient Plasma

3.3. The Level of Plasma Cathepsin D Does Not Correlate with Clinical Characteristics Potentially Related to AD

3.4. The Level of Plasma Cathepsin D Negatively Correlates with CDR-SB Scores

3.5. The Reduction of Plasma Cathepsin D of AD Patients Was Confirmed by ELISA

3.6. Multivariate ROC Curve Analysis Validated Plasma Cathepsin D as a Biomarker for AD

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spires-Jones, T.L.; Hyman, B.T. The intersection of amyloid beta and tau at synapses in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2014, 82, 756–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Strooper, B.; Karran, E. The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2016, 164, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Jacova, C.; Hampel, H.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Blennow, K.; DeKosky, S.T.; Gauthier, S.; Selkoe, D.; Bateman, R.; et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: The IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; Mattsson, N.; Scholl, M.; Hansson, O.; Zetterberg, H. Amyloid biomarkers in Alzheimer′s disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 36, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Mielke, M.M.; Rissman, R.A.; Lista, S.; Vanderstichele, H.; Zetterberg, H.; Lewczuk, P.; Posner, H.; Hall, J.; Johnson, L.; et al. Blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer disease: Current state of the science and a novel collaborative paradigm for advancing from discovery to clinic. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 13, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lashley, T.; Schott, J.M.; Weston, P.; Murray, C.E.; Wellington, H.; Keshavan, A.; Foti, S.C.; Foiani, M.; Toombs, J.; Rohrer, J.D.; et al. Molecular biomarkers of Alzheimer′s disease: Progress and prospects. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, L.; Baird, A.L.; Westwood, S.; Hye, A.; Dobson, R.; Thambisetty, M.; Lovestone, S. A Decade of Blood Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease Research: An Evolving Field, Improving Study Designs, and the Challenge of Replication. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 62, 1181–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olsson, B.; Lautner, R.; Andreasson, U.; Öhrfelt, A.; Portelius, E.; Bjerke, M.; Hölttä, M.; Rosén, C.; Olsson, C.; Strobel, G.; et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer′s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, G.E.; Richo, G. Isolation and characterization of a stable activation intermediate of the lysosomal aspartyl protease cathepsin D. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benes, P.; Vetvicka, V.; Fusek, M. Cathepsin D—Many functions of one aspartic protease. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2008, 68, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vidoni, C.; Follo, C.; Savino, M.; Melone, M.A.; Isidoro, C. The Role of Cathepsin D in the Pathogenesis of Human Neurodegenerative Disorders. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 845–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, M. Autophagy and Alzheimer′s Disease. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 37, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladror, U.S.; Snyder, S.W.; Wang, G.T.; Holzman, T.F.; Krafft, G.A. Cleavage at the amino and carboxyl termini of Alzheimer′s amyloid-beta by cathepsin D. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 18422–18428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khurana, V.; Elson-Schwab, I.; Fulga, T.A.; Sharp, K.A.; Loewen, C.A.; Mulkearns, E.; Tyynela, J.; Scherzer, C.R.; Feany, M.B. Lysosomal dysfunction promotes cleavage and neurotoxicity of tau in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Di Domenico, F.; Tramutola, A.; Perluigi, M. Cathepsin D as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer′s disease. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2016, 20, 1393–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cataldo, A.M.; Barnett, J.L.; Berman, S.A.; Li, J.; Quarless, S.; Bursztajn, S.; Lippa, C.; Nixon, R.A. Gene expression and cellular content of cathepsin D in Alzheimer′s disease brain: Evidence for early up-regulation of the endosomal-lysosomal system. Neuron 1995, 14, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cataldo, A.M.; Nixon, R.A. Enzymatically active lysosomal proteases are associated with amyloid deposits in Alzheimer brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 3861–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cataldo, A.M.; Paskevich, P.A.; Kominami, E.; Nixon, R.A. Lysosomal hydrolases of different classes are abnormally distributed in brains of patients with Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 10998–11002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwagerl, A.L.; Mohan, P.S.; Cataldo, A.M.; Vonsattel, J.P.; Kowall, N.W.; Nixon, R.A. Elevated levels of the endosomal-lysosomal proteinase cathepsin D in cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurochem. 1995, 64, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.L.; Chong, J.R.; Weng, J.; Howlett, D.; Halsey, A.; Lee, J.H.; Attems, J.; Aarsland, D.; Francis, P.T.; Chen, C.P.; et al. Lysosomal cathepsin D is upregulated in Alzheimer′s disease neocortex and may be a marker for neurofibrillary degeneration. Brain Pathol. 2019, 29, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morena, F.; Argentati, C.; Trotta, R.; Crispoltoni, L.; Stabile, A.; Pistilli, A.; di Baldassarre, A.; Calafiore, R.; Montanucci, P.; Basta, G.; et al. A Comparison of Lysosomal Enzymes Expression Levels in Peripheral Blood of Mild- and Severe-Alzheimer′s Disease and MCI Patients: Implications for Regenerative Medicine Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanelli, L.; Emiliani, C.; Massini, C.; Persichetti, E.; Orlacchio, A.; Pelicci, G.; Sorbi, S.; Hasilik, A.; Bernardi, G.; Orlacchio, A. Cathepsin D expression is decreased in Alzheimer′s disease fibroblasts. Neurobiol. Aging 2008, 29, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Zhang, K.; Tian, Z.Y.; Wang, T.; Shang, D.S.; Li, B.; Liu, D.X.; Fang, W.G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Decreased expression of cathepsin D in monocytes is related to the defective degradation of amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014, 42, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993, 43, 2412–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winblad, B.; Palmer, K.; Kivipelto, M.; Jelic, V.; Fratiglioni, L.; Wahlund, L.O.; Nordberg, A.; Backman, L.; Albert, M.; Almkvist, O.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment—Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.; Chang, J.; Blackstone, C. FAM21 directs SNX27-retromer cargoes to the plasma membrane by preventing transport to the Golgi apparatus. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holewinski, R.J.; Jin, Z.; Powell, M.J.; Maust, M.D.; Van Eyk, J.E. A fast and reproducible method for albumin isolation and depletion from serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Proteomics 2013, 13, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, Y.; Chen, A.F.; Zhao, J.; Gu, Y.J.; Fu, G.X. Serum levels of cathepsin D, sirtuin1, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase are correlatively reduced in elderly healthy people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, L.A.; Cupples, L.A.; Haines, J.L.; Hyman, B.; Kukull, W.A.; Mayeux, R.; Myers, R.H.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Risch, N.; van Duijn, C.M. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium. JAMA 1997, 278, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.C.; Ibrahim-Verbaas, C.A.; Harold, D.; Naj, A.C.; Sims, R.; Bellenguez, C.; DeStafano, A.L.; Bis, J.C.; Beecham, G.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer′s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1452–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Strittmatter, W.J.; Saunders, A.M.; Schmechel, D.; Pericak-Vance, M.; Enghild, J.; Salvesen, G.S.; Roses, A.D. Apolipoprotein E: High-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1977–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.; George-Hyslop, P.H.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Joo, S.H.; Rosi, B.L.; Gusella, J.F.; Crapper-MacLachlan, D.R.; Alberts, M.J.; et al. Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer′s disease. Neurology 1993, 43, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer′s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mueller, S.T. A note on ROC analysis and non-parametric estimate of sensitivity. Psychometrika 2005, 70, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simundic, A.-M. Diagnostic Accuracy—Part 1: Basic Concepts Sensitivity and Specificity, ROC Analysis, STARD Statement. Point Care 2012, 11, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Stachowiak, A.; Mamun, A.A.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Takeda, S.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bergantin, L.B.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Stankiewicz, A.M. Autophagy and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.R.; Gibson, A.M. Degradation of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid protein by human cathepsin D. Neuroreport 1996, 7, 2163–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemenschneider, M.; Blennow, K.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Andreasen, N.; Prince, J.A.; Laws, S.M.; Forstl, H.; Kurz, A. The cathepsin D rs17571 polymorphism: Effects on CSF tau concentrations in Alzheimer disease. Hum. Mutat. 2006, 27, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siintola, E.; Partanen, S.; Stromme, P.; Haapanen, A.; Haltia, M.; Maehlen, J.; Lehesjoki, A.E.; Tyynela, J. Cathepsin D deficiency underlies congenital human neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. Brain 2006, 129, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Awano, T.; Katz, M.L.; O’Brien, D.P.; Taylor, J.F.; Evans, J.; Khan, S.; Sohar, I.; Lobel, P.; Johnson, G.S. A mutation in the cathepsin D gene (CTSD) in American Bulldogs with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2006, 87, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinfeld, R.; Reinhardt, K.; Schreiber, K.; Hillebrand, M.; Kraetzner, R.; Bruck, W.; Saftig, P.; Gartner, J. Cathepsin D deficiency is associated with a human neurodegenerative disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 78, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suire, C.N.; Abdul-Hay, S.O.; Sahara, T.; Kang, D.; Brizuela, M.K.; Saftig, P.; Dickson, D.W.; Rosenberry, T.L.; Leissring, M.A. Cathepsin D regulates cerebral Abeta42/40 ratios via differential degradation of Abeta42 and Abeta40. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, M.; Shibata, M.; Waguri, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Tanida, I.; Kominami, E.; Gotow, T.; Peters, C.; von Figura, K.; Mizushima, N.; et al. Participation of autophagy in storage of lysosomes in neurons from mouse models of neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease). Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 167, 1713–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Droga-Mazovec, G.; Bojic, L.; Petelin, A.; Ivanova, S.; Romih, R.; Repnik, U.; Salvesen, G.S.; Stoka, V.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins trigger caspase-dependent cell death through cleavage of bid and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 homologues. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 19140–19150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakanishi, H. Neuronal and microglial cathepsins in aging and age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2003, 2, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, J.; Adair, B.; Reinheckel, T. Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3421–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kramer, L.; Turk, D.; Turk, B. The Future of Cysteine Cathepsins in Disease Management. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 873–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Wang, J.; Geng, C.; Li, Y.; Dong, L.; Liu, L.; Chang, Y.; Shen, J.; Nie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Tandem mass tag-based proteomic analysis reveals cathepsin-mediated anti-autophagic and pro-apoptotic effects under proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Aging 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, D.; Hamer, P.; Tenney, D.; Zabrecky, J. Elevated levels of pro-cathepsin-d in the plasma of breast-cancer patients. Int. J. Oncol. 1995, 6, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Yuan, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, W.; Wei, M.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Myocardial Upregulation of Cathepsin D by Ischemic Heart Disease Promotes Autophagic Flux and Protects Against Cardiac Remodeling and Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, A.; Mattsson, N.; Appelqvist, H.; Janefjord, C.; Sandin, L.; Agholme, L.; Olsson, B.; Svensson, S.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Lysosomal network proteins as potential novel CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromol. Med. 2014, 16, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Radisky, E.S. Cathepsin D: Regulation in mammary gland remodeling, misregulation in breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Qiao, L.; Hamamichi, S.; Caldwell, K.A.; Caldwell, G.A.; Yacoubian, T.A.; Wilson, S.; Xie, Z.L.; Speake, L.D.; Parks, R.; Crabtree, D.; et al. Lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D protects against alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. Mol. Brain 2008, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Licastro, F.; Pedrini, S.; Caputo, L.; Annoni, G.; Davis, L.J.; Ferri, C.; Casadei, V.; Grimaldi, L.M. Increased plasma levels of interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Peripheral inflammation or signals from the brain? J. Neuroimmunol. 2000, 103, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, R.J.; Palmer, R.F.; Royall, D.R. Serum interleukin (IL)-15 as a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y. Plasma cholesterol in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Transl. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamolodchikov, D.; Renne, T.; Strickland, S. The Alzheimer’s disease peptide beta-amyloid promotes thrombin generation through activation of coagulation factor XII. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Control (n = 19) | MCI (n = 8) | AD (n = 13) | VaD (n = 16) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 6/13 | 2/6 | 7/6 | 5/11 |

| Age (years) | 74 ± 3.4 | 67.8 ± 7.8 | 72.2 ± 7.6 | 74.7 ± 7.3 |

| Education duration (years) | 6.3 ± 3.5 | 6.0 ± 6.0 | 13.1 ± 3.7 | 6.6 ± 4.9 |

| MMSE | 26.9 ± 2.0 | 26 ± 3.0 | 24.4 ± 4.3 | 22.4 ± 5.2 |

| CDR | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| CDR-SB | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | 3.7 ± 3.9 |

| Amyloid PET | normal | normal | abnormal | normal |

| WMH | - | 1 | 1 | 2 or 3 |

| AD vs. Non-AD | AUC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | p-Value a | Cut Off | 95% CI of AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age + sex | 0.652 | 46.15 | 76.19 | 0.173 | 0.359 | 0.491 to 0.813 |

| Age + sex + cathepsin D | 0.780 | 61.54 | 80.95 | 0.036 | 0.278 | 0.625 to 0.909 |

| Age + sex + ApoE | 0.702 | 46.15 | 80.95 | 0.099 | 0.315 | 0.551 to 0.852 |

| Age + sex + ApoE + cathepsin D | 0.795 | 69.23 | 76.19 | 0.044 | 0.316 | 0.671 to 0.918 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.-W.; Jung, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Heo, H.; Hong, C.-H.; Seo, S.-W.; Choi, S.-H.; Son, S.-J.; Lee, S.; Chang, J. Identification of Cathepsin D as a Plasma Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010138

Kim J-W, Jung S-Y, Kim Y, Heo H, Hong C-H, Seo S-W, Choi S-H, Son S-J, Lee S, Chang J. Identification of Cathepsin D as a Plasma Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells. 2021; 10(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010138

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jae-Whan, Soon-Young Jung, Youngbin Kim, Hansol Heo, Chang-Hyung Hong, Sang-Won Seo, Seong-Hye Choi, Sang-Joon Son, Seongju Lee, and Jaerak Chang. 2021. "Identification of Cathepsin D as a Plasma Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease" Cells 10, no. 1: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010138

APA StyleKim, J.-W., Jung, S.-Y., Kim, Y., Heo, H., Hong, C.-H., Seo, S.-W., Choi, S.-H., Son, S.-J., Lee, S., & Chang, J. (2021). Identification of Cathepsin D as a Plasma Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells, 10(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010138