The Urban Heat Island Effect and the Role of Vegetation to Address the Negative Impacts of Local Climate Changes in a Small Brazilian City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (i)

- to analyze the influence of urban-geographical variables as triggering factors of the formation of heat islands;

- (ii)

- to propose a model to estimate and spatialize the maximum intensity of UHIs in the city core; and

- (iii)

- to simulate the mitigation of urban heat islands with an increase in vegetation index (NDVI) by using multiple linear regression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Methodology and Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

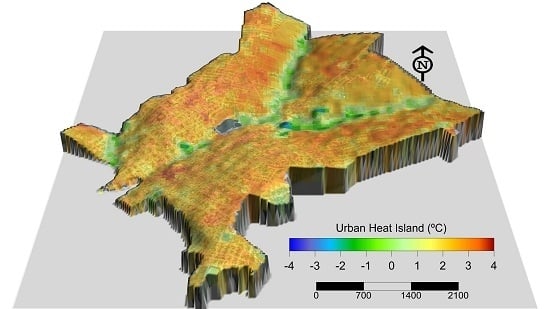

3.1. A Case Study of a Hot and Dry Night (21 October 2014) in the Iporá Region

3.2. Multiple Linear Regression of Maximum Heat Islands

3.3. The Influence of Vegetation on the Mitigation of Urban Heat Island Patterns

3.4. Simulation of the Maximum Urban Heat Island in a Highly Built Density Area of Iporá

4. Conclusions

- 1

- The urban-geographical variables NDVI and UI were those that contributed the most to explain the variability in the maximum UHI.

- 2

- It was observed that the areas located in the valleys had lower thermal values, suggesting a cold air drainage as defined by Lopes [42].

- 3

- During the occurrence of a maximum UHI, UHI > 1 °C classes had an area of approximately 15,000 km2, which corresponded to 90% of the urban area.

- 4

- With the increase in NDVI, the UHI gradually decreased: the areas close to the Tamanduá stream significantly decreased the values of UHI, or even presented a negative UHI (−4 °C, also known as cool islands), in simulations with NDVI increased by 80% and 100%.

- 5

- In some areas of the city, there was little decrease in the intensity of UHIs due to little or no greening. Therefore, even with a 100% increase in NDVI, it would be too low and insufficient to significantly minimize UHIs.

- 6

- The frequency of cool island classes increased with the increase in NDVI. The cool island class −5 °C to −4 °C was only observed in the simulation with a 100% increase in NDVI. There was also a decrease in UHI classes 3–4 °C and 4–5 °C and an increase in low intensity classes due to the migration of more intense UHI to lower intensity classes.

- 7

- With the increase in NDVI in the central area of a maximum UHI (dense urban area), there was a perceptible and significant decrease in its intensity and size (a 45% area decrease).

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miao, S.; Chen, F.; LeMone, M.A.; Tewari, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. An observational and modeling study of characteristics of urban heat island and boundary layer structures in Beijing. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2009, 48, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. City size and the urban heat island. Atmos. Environ. 1973, 7, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnfield, A.J. Two decades of urban climate research: A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. 2003, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Alves, E.; Alcoforado, M.J.; Machete, R. Lisbon urban heat island updated: New highlights about the relationships between thermal patterns and wind regimes. Adv. Meteorol. 2013, 2013, 487695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Goh, K. The relationship between height to width ratios and the heat island intensity at 22:00 h for Singapore. Int. J. Climatol. 1999, 19, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Montávez, J.P.; Rodríguez, A.; Jiménez, J.I. A study of the urban heat island of Granada. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 20, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, R.A.; Leung, D.Y.C.; Liu, C.-H. An investigation of urban heat island intensity (UHII) as an indicator of urban heating. Atmos. Res. 2009, 94, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.-K. Heat islands—Understanding and mitigating heat in urban areas. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2012, 69, 1008–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Potchter, O.; Bitan, A.; Boltansky, D.; Yaakov, Y. Microclimate modelling of street tree species effects within the varied urban morphology in the Mediterranean city of Tel Aviv, Israel. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 30, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Canyon geometry and the nocturnal urban heat island: Comparison of scale model and field observations. J. Climatol. 1981, 1, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartland, L. Ilhas de Calor: Como Mitigar Zonas de Calor em Áreas Urbanas; Oficina de textos: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Szűcs, Á. Wind comfort in a public urban space—Case study within Dublin Docklands. Front. Archit. Res. 2013, 2, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcoforado, M.-J.; Andrade, H.; Lopes, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Vieira, R. Observational studies on summer winds in Lisbon (Portugal) and their influence on daytime regional and urban thermal patterns. Merhavim 2006, 6, 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmond, C.S.B.; King, T.S.; Cropley, F.D.; Nowak, D.J.; Souch, C. Local-scale fluxes of carbon dioxide in urban environments: Methodological challenges and results from Chicago. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 116, S243–S254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Boundary Layer Climates, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1987; pp. 1–435. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu, M.; Morefield, P.E.; Bierwagen, B.G.; Weaver, C.P. Urban adaptation can roll back warming of emerging megapolitan regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2909–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Conry, P.; Fernando, H.J.S.; Hamlet, A.F.; Hellmann, J.J.; Chen, F. Green and cool roofs to mitigate urban heat island effects in the Chicago metropolitan area: Evaluation with a regional climate model. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffee, J.E.; Parzen, J.; Wagstaff, M.; Lewis, R.S. Preparing for a changing climate: The Chicago climate action plan’s adaptation strategy. J. Great Lakes Res. 2010, 36 (Suppl. 2), 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcoforado, M.-J.; Andrade, H. Nocturnal urban heat island in Lisbon (Portugal): Main features and modelling attempts. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2006, 84, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charabi, Y.; Bakhit, A. Assessment of the canopy urban heat island of a coastal arid tropical city: The case of Muscat, Oman. Atmos. Res. 2011, 101, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, T.; Wolters, D. Measurement and statistical modeling of the urban heat island of the city of Utrecht (the Netherlands). J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2012, 51, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalakakou, G.; Flocas, H.A.; Santamouris, M.; Helmis, C.G. Application of Neural networks to the simulation of the heat island over Athens, Greece, using synoptic types as a predictor. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2002, 41, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, T.S.; Shimada, T.; Hoshi, H. Modeling and simulation of the Tokyo urban heat island. Atmos. Environ. 1996, 30, 3431–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R.; Krayenhoff, E.S. Evaluation of the ‘local climate zone’ scheme using temperature observations and model simulations. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 1062–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, J.; Bottyán, Z.; Gulyás, A.; Kevei-Bárány, I. Urban temperature excess as a function of urban parameters in szeged, part 2: Statistical model equations. Acta Climatol. Chorol. 2001, 34–35, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- László, E.; Szegedi, S. A multivariate linear regression model of mean maximum urban heat island: A case study of Beregszász (Berehove), Ukraine. Q. J. Hungarian Meteorol. Serv. 2015, 119, 409–423. [Google Scholar]

- Bottyán, Z.; Unger, J. A multiple linear statistical model for estimating the mean maximum urban heat island. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2003, 75, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.A.; Sailor, D.J. Quantifying the influence of land-use and surface characteristics on spatial variability in the urban heat island. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2008, 95, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcoforado, M.-J.; Andrade, H.; Lopes, A.; Vasconcelos, J. Application of climatic guidelines to urban planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE, Cidades. 2015. Available online: http://www.cidades.ibge.gov.br/ (accessed on 1 September 2016).

- Oke, T.R. Initial Guidance to Obtain Representative Meteorological Observations at Urban Sites; IOM Report No. 81, WMO/TD. No. 1250; World Meteorological Organization (WMO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Vide, J.; Sarricolea, P.; Moreno-García, M.C. On the definition of urban heat island intensity: The ‘rural’ reference. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, E. Seasonal and spatial variation of surface urban heat island intensity in a small urban agglomerate in Brazil. Climate 2016, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, M.; Jayamana, S.; Tsujiko, Y. Relation between social and environmental conditions in Colombo Sri Lanka and the urban index estimated by satellite remote sensing data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 1996, XXXI, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- As-syakur, A.R.; Adnyana, I.W.S.; Arthana, I.W.; Nuarsa, I.W. Enhanced built-up and bareness index (EBBI) for mapping built-up and bare land in an urban area. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 2957–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapponi, J.C. Estatistica Usando Excel, 4th ed.; CAMPUS—RJ: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gál, T.; Balázs, B.; Geiger, J. Modelling the maximum development of urban heat island with the application of gis based surface parameters in szeged (part 2): Stratified sampling and the statistical model. Acta Climatol. Chorol. 2005, 38–39, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, J. Modelling of the annual mean maximum urban heat island using 2D and 3D surface parameters. Clim. Res. 2006, 30, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jauregui, E. Heat Island Development in Mexico City. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 3821–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Su, C.; Zhang, Y. Research on the microclimate characteristics and cold island effect over a reservoir in the Hexi Region. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 1988, 5, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A. Drenagem e acumulação de ar frio em noites de arrefecimento radiativo. Um exemplo no vale de Barcarena (Oeiras). Finisterra 1995, 30, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancoso, R.; Sano, E.E.; Meneses, P.R. The spectral changes of deforestation in the Brazilian tropical savanna. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Ji, C.; Jiang, X.; Zhong, J. Relationship between NDVI and the urban heat island effect in Beijing area of China. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2005, 5884, 58841R. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey, C.W.; Lee, X.; Smith, R.B. Remotely sensing the cooling effects of city scale efforts to reduce urban heat island. Build. Environ. 2012, 49, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sites | A 1 | TS 1 | DD 2 | NDVI 1 | TA 3 | UI 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 608.3 | 1 | 684.4 | 0.05 | 213 | −0.09 |

| 2 | 570.6 | 2.4 | 3560.3 | 0.26 | 190 | −0.27 |

| 3 | 588.8 | 2.1 | 2103 | 0.07 | 208 | 0 |

| 4 | 580.8 | 2.7 | 70.6 | 0.01 | 296 | 0.06 |

| 5 | 596.9 | 3.3 | 4002 | 0.08 | 280 | −0.02 |

| 6 | 615.1 | 1.7 | 2084.6 | 0.08 | 282 | 0.01 |

| 7 | 595.8 | 2.4 | 912.6 | 0.09 | 233 | −0.02 |

| Estimated UHI | Number of Equations |

|---|---|

| Equation (5) | |

| Equation (6) | |

| Equation (7) |

| Simulated UHI | Equations | Number of Equations |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum UHI | Equation (7) | |

| Simulated UHI 1 | Equation (8) | |

| Simulated UHI 2 | Equation (9) | |

| Simulated UHI 3 | Equation (10) | |

| Simulated UHI 4 | Equation (11) | |

| Simulated UHI 5 | Equation (12) |

| Statistics | UHI (Observed) | UHI_1 | UHI_2 | UHI_3 | UHI_4 | UHI_5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Simulated) | ||||||

| (1.2 × NDVI) | (1.4 × NDVI) | (1.6 × NDVI) | (1.8 × NDVI) | (2 × NDVI) | ||

| Minimum | −1.79 | −2.48 | −2.75 | −3.08 | −3.71 | −4.27 |

| Maximum | 4.40 | 4.50 | 4.35 | 4.27 | 4.34 | 4.35 |

| Mean | 2.99 | 2.86 | 2.74 | 2.62 | 2.49 | 2.37 |

| Median | 3.21 | 3.11 | 3.01 | 2.90 | 2.80 | 2.69 |

| First quartile | 2.75 | 2.61 | 2.46 | 2.31 | 2.15 | 2.01 |

| Third quartile | 3.49 | 3.42 | 3.33 | 3.25 | 3.18 | 3.11 |

| Variance | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.19 | 1.38 |

| Standard deviation | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 1.17 |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lima Alves, E.D.; Lopes, A. The Urban Heat Island Effect and the Role of Vegetation to Address the Negative Impacts of Local Climate Changes in a Small Brazilian City. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos8020018

Lima Alves ED, Lopes A. The Urban Heat Island Effect and the Role of Vegetation to Address the Negative Impacts of Local Climate Changes in a Small Brazilian City. Atmosphere. 2017; 8(2):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos8020018

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima Alves, Elis Dener, and António Lopes. 2017. "The Urban Heat Island Effect and the Role of Vegetation to Address the Negative Impacts of Local Climate Changes in a Small Brazilian City" Atmosphere 8, no. 2: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos8020018

APA StyleLima Alves, E. D., & Lopes, A. (2017). The Urban Heat Island Effect and the Role of Vegetation to Address the Negative Impacts of Local Climate Changes in a Small Brazilian City. Atmosphere, 8(2), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos8020018