Soil Layer Development and Biota in Bioretention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Sites

2.2. Field Sampling

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Baseline Physical Data

4.1.1. Soil Texture

4.1.2. Soil Organic Matter Enrichment

4.2. Soil Biota

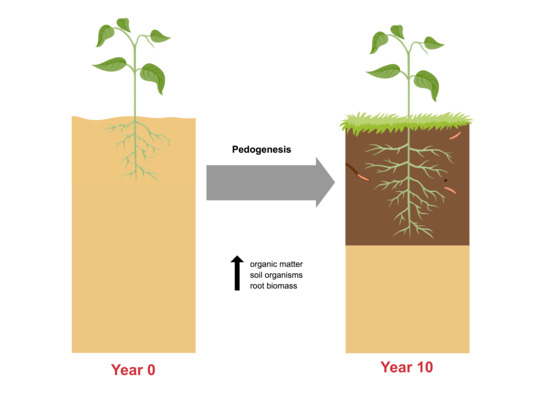

4.3. Evidence of Pedogenesis

4.4. Confounding Factors

4.5. Sources of Error in Animal Sampling

4.6. Application to Bioretention Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, D.; Watson-Stegner, D. Evolution model of pedogenesis. Soil Sci. 1987, 143, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.; Weil, R. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 13th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Davis, A.P. Heavy metal capture and accumulation in bioretention media. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5247–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Davis, A.P. Urban particle capture in bioretention media. I: Laboratory and field studies. J. Environ. Eng. 2008, 134, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, C.H.; Traver, R.G. Multiyear and seasonal variation of infiltration for storm-water best management practices. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2008, 134, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert Jenkins, J.K.; Wadzuk, B.M.; Welker, A.L. Fines accumulation and distribution in a storm-water rain garden nine years postconstruction. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2010, 136, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Coustumer, S.; Fletcher, T.D.; Deletic, A.; Barraud, S.; Lewis, J.F. Hydraulic performance of biofilter systems for stormwater management: Influences of design and operation. J. Hydrol. 2009, 376, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, H. Factors of Soil Formation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T. Space-for-time substitution as an alternative to long-term studies. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology: Approaches and Alternatives; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 110–135. [Google Scholar]

- Leisman, G.A. A vegetation and soil chronosequence on the Mesabi Iron Range Spoil Banks, Minnesota. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, P.C. Succession as an alternative for reclaiming phosphate spoil mounds. In Studies on Phosphate Mining, Reclamation and Energy; Center for Wetlands, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Frouz, J.; Keplin, B.; Pizl, V.; Tajovsky, K.; Stary, J.; Lukesov, A.; Novkov, A.; Balk, V.; Hnel, L.; Materna, J.; et al. Soil biota and upper soil layers development in two contrasting post-mining chronosequences. Ecol. Eng. 2001, 17, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sangregorio, M.; Trasar-Cepeda, M.; Leiros, M.; Gil-Sotres, F.; Guitian-Ojea, F. Early stages of lignite mine soil genesis: Changes in biochemical properties. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1991, 23, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Daniels, W.; Bell, J.; Burger, J. Early stages of mine soil genesis as affected by topsoiling and organic amendments. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1988, 52, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Daniels, W.; Bell, J.; Burger, J. Early stages of mine soil genesis in a southwest Virginia spoil lithosequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1988, 52, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobat, J.; Aragno, M.; Matthey, W. The Living Soil: Fundamentals of Soil Science and Soil Biology; Science Publishers: Enfield, NH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oades, J. The role of biology in the formation, stabilization and degradation of soil structure. Geoderma 1993, 56, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogerkamp, M.; Rogaar, H.; Eijsackers, H. Effect of earthworms on grassland on recently reclaimed polder soils in the Netherlands. In Earthworm Ecology: From Darwin to Vermiculture; Satchell, J., Ed.; Chapman and Hall, Ltd.: London, UK, 1983; pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Department of the Environment. Maryland Stormwater Design Manual; State of Maryland: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000.

- American Society for Testing and Materials. Standard Test Methods for Moisture, Ash, and Organic Matter of Peat and Other Organic Soils; Technical Report ASTM D2974-00; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Csuzdi, C.; Slavecz, K. Lumbricus friendi Cognetti, 1904, a new exotic earthworm in North America. Northeast. Nat. 2003, 10, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J. The earthworms of Maryland (Oligochaeta: Acanthodrilidae, Lumbricidae, Megasolecidae and Sparganophilidae). Megadrilogica 1974, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, G.; Barrett, V. Earthworm Identifier; CSIRO: Melbourne, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, T. Earthworms of the northeastern United States: A key, with distribution records. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1942, 32, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Fender, W.M.; McKey-Fender, D. Oligochaeta: Megascolecidae and other earthworms from western North America. In Soil Biology Guide; Dindal, D.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 357–377. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. The genus Pheretima in North America. Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. Harvard Univ. 1937, 80, 339–373. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. On some species of the oriental earthworm genus Pheretima Kinberg, 1867, with key to species reported from the Americas. Am. Mus. Novit. 1958, 1888, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. Contributions to North American Earthworms (Annelida), No. 4: On American earthworm genera. I. Eisenoides (Lumbricidae). Bull. Tall Timbers Res. Stn. 1972, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. Contributions to North American Earthworms (Annelida), No. 5: On variation in another anthropochorous species of the oriental earthworm genus Pheretima Kinberg 1866 (Megascolecidae). Bull. Tall Timbers Res. Stn. 1972, 3, 18–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. Contributions to North American Earthworms (Annelida), No. 8: The Earthworm Genus Octolasion in America. Bull. Tall Timbers Res. Stn. 1973, 4, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. Contributions to North American Earthworms (Annelida), No. 10: Contributions to a revision of the Lumbricidae. X., Dendrobaena octaedra (Savigny) 1826, with special reference to the importance of its parthenogenetic polymorphism for the classification of earthworms. Bull. Tall Timbers Res. Stn. 1974, 5, 15–57. [Google Scholar]

- James, W.M. Oligochaeta: Megascolecidae and other earthworms from southern and midwestern North America. In Soil Biology Guide; Dindal, D.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. The Earthworm Fauna of New Zealand; New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research: Wellington, New Zealand, 1959.

- Reynolds, J.W.; Clebsch, E.E.C.; Reynolds, W.M. Contributions to North American Earthworms (Oligochaeta), No. 13: The Earthworms of Tennessee (Oligochaeta). I. Lumbricidae. Bull. Tall Timbers Res. Stn. 1974, 3, 1–133. [Google Scholar]

- Schwert, D.P. Oligochaeta: Lumbricidae. In Soil Biology Guide; Dindal, D.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, R.W.; Gerard, B.M.; Barnes, R.S.K.; Crothers, J.H. Earthworms. Synopses of the British Fauna; Linnean Society of London: Shrewsbury, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Worm Watch Canada Field Guide to Earthworms. Available online: https://www.naturewatch.ca/wormwatch/how-to-guide/identifying-earthworms/ (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Ayers, E.M. Pedogenesis in Rain Gardens: The Role of Earthworms and Other Organisms in Long-Term Soil Development. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, R.R.; Islam, K.R.; Stine, M.A.; Gruver, J.B.; Samson-Liebig, S.E. Estimating active carbon for soil quality assessment: A simplified method for lab and field use. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2003, 18, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Six, J.; Bossuyt, J.; Degryze, S.; Denef, K. A history of research on the link between (micro)aggregates, soil biota, and soil organic matter dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2004, 79, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, F. Effects of animals on the soil. Geoderma 1981, 25, 75–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J. Factors affecting earthworm abundance in soils. In Earthworm Ecology; Edwards, C., Ed.; St. Lucie Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, P.; Walker, T. The chronosequence concept and soil formation. Q. Rev. Biol. 1970, 45, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwood, T.; Henderson, P. Ecological Methods, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Malden, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- LeFevre, G.H.; Paus, K.H.; Natarajan, P.; Gulliver, J.S.; Novak, P.J.; Hozalski, R.M. Review of dissolved pollutants in urban storm water and their removal and fate in bioretention cells. J. Environ. Eng. 2014, 141, 04014050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Identifier | Location | Year of Construction | Age at Sampling (Years) | Bioretention Media Specification (Volume Basis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMCP | University of Maryland College Park, MD | 2004 | 1 | 50% sand |

| 30% topsoil—sandy loam or loamy sand | ||||

| 20% shredded 2 × hardwood mulch | ||||

| WNY | Washington Navy Yard Washington, DC | 2002 | 2 | 50% sand |

| 30% topsoil—sandy loam or loamy sand | ||||

| 20% shredded 2 × hardwood mulch | ||||

| MJES | Mary Harris ”Mother” Jones Elementary School Adelphi, MD | 2002 | 3 | 50% sand |

| 25% topsoil—sandy loam or loam | ||||

| 25% compost | ||||

| CBF | Philip Merrill Environmental Center Annapolis, MD | 2001 | 4 | 60–65% loamy sand |

| 35–40% compost | ||||

| OR | ||||

| 30% sandy loam | ||||

| 30% coarse sand | ||||

| 40% compost 1 | ||||

| NWHS | Northwestern High School Hyattsville, MD | 1999 | 5 | 50% sand |

| 25% topsoil | ||||

| 25% compost | ||||

| PP | Inglewood Center III Upper Marlboro, MD | 1999 | 5 | 70% sand |

| 30% compost | ||||

| CF | Claggett Farm Upper Marlboro, MD | 1999 | 6 | Unavailable |

| CC | Chevy Chase Bank Silver Spring, MD | 1998 | 7 | Unavailable |

| BP | Beltway Plaza Mall Greenbelt, MD | 1997 | 7 | 83% topsoil—loam, sandy loam, clay loam, silt loam, sandy clay loam, or loamy sand |

| 17% peat moss or rotted manure | ||||

| LRH | Laurel Regional Hospital Laurel, MD | 1994 | 10 | Unavailable |

| Site | Sand (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) | d60/d10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface (0–10 cm) | ||||

| UMCP | 87.7 (88.3–92.1) | 7.3 (2.8–8.2) | 4.3 (4.0–5.1) | 10 |

| WNY | 71.8 (68.1–75.0) | 21.7 (21.0–26.4) | 5.4 (3.9–6.5) | 10 |

| MJES | 49.9 (43.1–78.7) | 31.8 (13.2–41.3) | 15.6 (8.1–18.3) | 50 |

| CBF | 60.6 (59.8–62.6) | 14.5 (14.0–16.9) | 22.9 (22.5–26.2) | 50 |

| NWHS | 51.3 (50.3–57.6) | 32.1 (32.1–34.7) | 15.0 (10.3–16.6) | 50 |

| PP | 69.6 (62.9–79.1) | 13.2 (8.3–17.5) | 17.2 (12.6–19.6) | 50 |

| CF | 69.9 (67.5–72.6) | 17.9 (16.6–18.0) | 12.1 (10.8–14.5) | 50 |

| CC | 67.0 (43.8–76.4) | 28.3 (21.3–43.5) | 4.6 (2.3–12.7) | 5 |

| BP | 60.0 (53.7–72.8) | 17.9 (10.6–20.1) | 22.1 (16.6–26.2) | 50 |

| LRH | 59.2 (22.6–59.4) | 21.2 (20.7–46.0) | 17.5 (16.4–20.1) | 50 |

| Sub-Surface (10–20 cm) | ||||

| UMCP | 91.4 (91.4–93.8) | 4.0 (4.0–5.1) | 2.2 (2.2–3.6) | 10 |

| WNY | 72.4 (67.9–75.6) | 19.7 (17.1–26.8) | 7.3 (5.2–7.9) | 10 |

| MJES | 60.4 (57.2–96.3) | 21.0 (1.2–21.2) | 18.6 (2.5–21.6) | 50 |

| CBF | 60.8 (59.8–61.8) | 17.4 (16.5–17.5) | 22.7 (20.7–22.8) | 50 |

| NWHS | 40.1 (38.1–51.9) | 42.4 (31.0–46.7) | 17.1 (13.2–19.5) | 20 |

| PP | 87.9 (83.8–88.1) | 4.3 (4.2–11.9) | 7.6 (4.3–7.9) | 10 |

| CF | 67.5 (65.1–70.2) | 18.5 (16.8–19.8) | 13.0 (12.7–16.4) | 50 |

| CC | 48.0 (32.3–81.4) | 37.0 (15.3–56.1) | 11.6 (3.3–15.0) | 50 |

| BP | 54.9 (53.3–55.1) | 23.4 (21.1–24.0) | 22.7 (21.5–24.0) | 50 |

| LRH | 39.0 (35.6–62.4) | 25.4 (22.0–46.1) | 18.2 (12.1–39.0) | 20 |

| Sub-Sub-Surface (20–30 cm) | ||||

| UMCP | 92.0 (91.3–92.6) | 4.1 (3.8–5.4) | 3.6 (3.3–3.9) | 10 |

| WNY | 68.9 (66.5–75.2) | 25.6 (7.0–26.8) | 6.7 (5.5–17.8) | 10 |

| MJES | 57.2 (53.1–96.2) | 19.9 (1.6–25.8) | 21.1 (2.2–22.9) | 50 |

| CBF | 61.4 (60.6–61.8) | 16.9 (16.5–18.3) | 21.7 (19.9–22.9) | 50 |

| NWHS | 52.7 (52.1–68.5) | 30.9 (24.0–33.9) | 14.0 (7.5–16.4) | 50 |

| PP | 89.2 (87.8–92.2) | 4.2 (1.5–7.5) | 6.3 (3.3–8.0) | 10 |

| CF | 62.8 (61.2–64.9) | 17.4 (16.8–18.0) | 19.2 (17.7–22.0) | 20 |

| CC | 53.1 (46.7–93.8) | 31.0 (3.8–39.1) | 14.2 (2.4–15.9) | 50 |

| BP | 44.8 (27.7–44.8) | 34.9 (21.1–38.6) | 23.8 (20.4–33.7) | 20 |

| LRH | 40.3 (22.6–59.4) | 40.1 (21.1–57.1) | 19.6 (19.5–20.3) | 20 |

| Taxonomic Group | UMCP | WNY | MJES | CBF | NWHS | PP | CF | CC | BP | LRH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbricidae (Earthworms) | 13 | 17 | 145 | 47 | 86 | 16 | 16 | 84 | 52 | 65 |

| Coleoptera (Beetles—adults and larvae) | 5 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 19 | 38 | 25 | 12 | 3 | 5 |

| Formicidae (Ants) | 1 | - | 8 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 148 | 22 | 10 | 2 |

| Enchytraeidae (Pot Worms) | - | - | 26 | 26 | 34 | 3 | - | 3 | - | - |

| Collembola (Springtails) | - | - | 23 | 23 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Chilopoda (Centipedes) | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 6 | 29 | 3 | 1 |

| Isopoda (Pill bugs) | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Diplopoda (Millipedes) | 1 | - | 3 | 3 | 1 | - | 7 | - | 1 | 3 |

| Araneae (Spiders) | 1 | - | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | - | - |

| Acari (Mites) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Gastropoda (Snails) | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Diptera (Flies—larvae) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Unidentified Insect Larvae | - | - | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | - |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitchell Ayers, E.; Kangas, P. Soil Layer Development and Biota in Bioretention. Water 2018, 10, 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111587

Mitchell Ayers E, Kangas P. Soil Layer Development and Biota in Bioretention. Water. 2018; 10(11):1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111587

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitchell Ayers, Emily, and Patrick Kangas. 2018. "Soil Layer Development and Biota in Bioretention" Water 10, no. 11: 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111587

APA StyleMitchell Ayers, E., & Kangas, P. (2018). Soil Layer Development and Biota in Bioretention. Water, 10(11), 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10111587