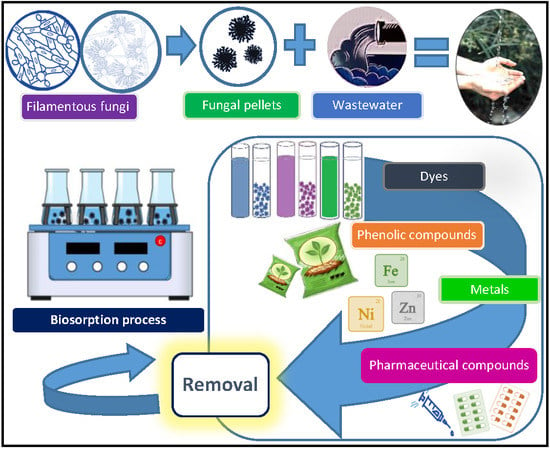

Biosorption of Water Pollutants by Fungal Pellets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Biosorption of Some Relevant Water Pollutants by Fungal Pellets

2.1. Heavy Metals

2.1.1. Effect of pH on Biosorption of Metals

2.1.2. Effect of Initial Metal Concentration on Biosorption

2.1.3. Effect of Diameter of Pellets on Biosorption of Metals

2.1.4. Effect of Pretreatment of Fungal Pellets on Biosorption of Metals

2.1.5. Biosorption of Heavy Metals Form Mixtures

2.1.6. Effects of Anions on the Biosorption of Metals

2.2. Dyes

2.3. Phenolic Compounds

2.4. Other Organic Compounds: Pesticides and Humic Substances

2.5. Pharmaceutical Compounds

3. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhainsa, K.C.; D’Souza, S.F. Removal of copper ions by the filamentous fungus, Rhizopus oryzae from aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3829–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, S. Efficient decolorization of dye-containing wastewater using mycelial pellets formed of marine-derived Aspergillus niger. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 25, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizullah, A.; Khattak, M.N.K.; Richter, P.; Häder, D.P. Water pollution in Pakistan and its impact on public health-a review. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir-Tutusaus, J.A.; Baccar, R.; Caminal, G.; Sarrà, M. Can white-rot fungi be a real wastewater treatment alternative for organic micropollutants removal? A review. Water Res. 2018, 138, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodarte-Morales, A.I.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T.; Lema, J.M. Biotransformation of three pharmaceutical active compounds by the fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium in a fed batch stirred reactor under air and oxygen supply. Biodegradation 2012, 23, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, Z. Application of biosorption for the removal of organic pollutants: A review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 997–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Ortiz, E.J.; Rene, E.R.; Pakshirajan, K.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Lens, P.N. Fungal pelleted reactors in wastewater treatment: Applications and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.C.; Cheng, C.L.; Han, Y.L.; Chen, B.Y.; Chang, J.S. Recovery of high-value metals from geothermal sites by biosorption and bioaccumulation. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, D.; Huang, R.; Yang, M.; Zhang, S.; Dou, X.; Wang, D.; Vimonses, V. Binding mechanisms and QSAR modeling of aromatic pollutant biosorption on Penicillium oxalicum biomass. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, Z.; Tatli, A.Í.; Tunç, Ö. A comparative adsorption/biosorption study of Acid Blue 161: Effect of temperature on equilibrium and kinetic parameters. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 142, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volesky, B. Detoxification of metal-bearing effluents: Biosorption for the next century. Hydrometallurgy 2001, 59, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgariu, L.; Escudero, L.B.; Bello, O.S.; Iqbal, M.; Nisar, J.; Adegoke, K.A.; Alakhras, F.; Kornaros, M.; Anastopoulos, I. The utilization of leaf-based adsorbents for dyes removal: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadhasivam, S.; Savitha, S.; Swaminathan, K.; Lin, F.H. Metabolically inactive Trichoderma harzianum mediated adsorption of synthetic dyes: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2009, 40, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, G.; Çelik, G.; Arica, M.Y. Studies on accumulation of uranium by fungus Lentinus sajor-caju. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguilimotan, L.C.; Bitacura, J.G. Biosorption of cadmium by filamentous fungi isolated from coastal water and sediments. J. Toxicol. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, M.; Aguirre, J.; Bartnicki-García, S.; Braus, G.H.; Feldbrügge, M.; Fleig, U.; Hansberg, W.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Kämper, J.; Kück, U.; et al. Fungal morphogenesis, from the polarized growth of hyphae to complex reproduction and infection structures. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2018, 82, e00068-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, Y.; Viraraghavan, T. Fungal decolorization of dye wastewater: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 79, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagianni, M. Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2004, 22, 189–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Reyes, M.; Beltrán-Hernández, R.I.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, G.A.; Coronel-Olivares, C.; Medina-Moreno, S.A.; Juárez-Santillán, L.F.; Lucho-Constantino, C.A. Formation, morphology and biotechnological applications of filamentous fungal pellets: A review. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quim. 2017, 3, 703–720. [Google Scholar]

- Marco-Urrea, E.; Pérez-Trujillo, M.; Cruz-Morató, C.; Caminal, G.; Vincent, T. Degradation of the drug sodium diclofenac by Trametes versicolor pellets and identification of some intermediates by NMR. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 176, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, B.T.; Ting, Y.P.; Deng, S. Surface modification of Penicillium chrysogenum mycelium for enhanced anionic dye removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 141, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casieri, L.; Varese, G.C.; Anastasi, A.; Prigione, V.; Svobodova, K.; Marchisio, V.F.; Novotný, Č. Decolorization and detoxication of reactive industrial dyes by immobilized fungi Trametes pubescens and Pleurotus ostreatus. Folia Microbiol. 2008, 53, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, A.; Viraraghavan, T. Biosorption of heavy metals on Aspergillus niger: Effect of pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 1998, 63, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M.A. Phytoremediation of heavy metals-Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burakov, A.E.; Galunin, E.V.; Burakova, I.V.; Kucherova, A.E.; Agarwal, S.; Tkachev, A.G.; Gupta, V.K. Adsorption of heavy metals on conventional and nanostructured materials for wastewater treatment purposes: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 148, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.A. New trends in removing heavy metals from industrial wastewater. Arab. J. Chem. 2011, 4, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbas, S.H.; Ismail, I.M.; Mostafa, T.M.; Sulaymon, A.H. Biosorption of heavy metals: A review. J. Chem. Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, 74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, H.M.; Eweida, E.A.; Farag, A. Heavy Metals in Drinking Water and Their Environmental Impact on Human Health; ICEHM2000; Cairo University: Giza, Egypt, 2000; pp. 542–556. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Cao, Q.; Zheng, Y.M.; Huang, Y.Z.; Zhu, Y.G. Health risks of heavy metals in contaminated soils and food crops irrigated with wastewater in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 152, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassef, E.; El-Taweel, Y.A. Removal of copper from wastewater by cementation from simulated leach liquors. J. Chem. Eng. Process Technol. 2015, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thangavel, P.; Subbhuraam, C.V. Phytoextraction: Role of hyperaccumulators in metal contaminated soils. Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. Part B 2004, 70, 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okeimen, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, riks and best available strategies for remediation. ISRN Ecol. 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Memon, A.R.; Aktoprakligil, D.; Özdemír, A.; Vertii, A. Heavy metal accumulation and detoxification mechanisms in plants. Turk. J. Bot. 2001, 25, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Ali, M.; Shah, Z. Characteristics of industrial effluents and their possible impacts on quality of underground water. Soil Environ. 2006, 25, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Hesham, A.E.L.; Qiao, M.; Rehman, S.; He, J.Z. Effects of Cd and Pb on soil microbial community structure and activities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2010, 17, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, S.; Kurniawan, T.A. Cr(VI) removal from synthetic wastewater using coconut shell charcoal and commercial activated carbon modified with oxidizing agents and/or chitosan. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudipalli, A. Metals (micro nutrients or toxicants) & Global Health. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008, 128, 331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Das, N. Recovery of precious metals through biosorption—A review. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 103, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Chardi, A.; Ribeiro, C.A.O.; Nadal, J. Metals in liver and kidneys and the effects of chronic exposure to pyrite mine pollution in the shrew Crocidura russula inhabiting the protected wetland of Doñana. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metals ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, H.D.; Kumbur, H.; Saha, B.; Van Leeuwen, J.H. Use of Rhizopus oligosporus produced from food processing wastewater as a biosorbent for Cu (II) ions removal from the aqueous solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4943–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Chan, G.Y.; Lo, W.H.; Babel, S. Physico-chemical treatment techniques for wastewater laden with heavy metals. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 118, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayangbenro, A.S.; Babalola, O.O. A new strategy for heavy metal polluted environments: A review of microbial biosorbents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudhoo, A.; Garg, V.K.; Wang, S. Removal of heavy metals by biosorption. Environ. Chem. 2011, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M. Removal of heavy metals from the environment by biosorption. Eng. Life Sci. 2004, 4, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, S.; Kurniawan, T.A. Low-cost adsorbents for heavy metals uptake from contaminated water: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 97, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhainsa, K.C.; D’Souza, S.F. Thorium biosorption by Aspergillus fumigatus, a filamentous fungal biomass. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 165, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.H.; Volesky, B. Biosorption: A solution to pollution? Int. Microbiol. 2000, 3, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M. Interactions of fungi with toxic metals. New Phytol. 1993, 124, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowroński, T.; Pirszel, J.; Skowrońska, B.P. Heavy metal removal by waste biomass of Penicillium chrysogenum. Water Qual. Res. J. Can. 2001, 36, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.M.; Tobin, J.M. Adsorption of metal ions by Rhizopus arrhizus biomass: Characterization studies. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1994, 16, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, G.; Arica, M.Y. Removal of heavy mercury (II), cadmium (II) and zinc (II) metal ions by live and heat inactivated Lentinus edodes pellets. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 143, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filipović-Kovačević, Ž.; Sipos, L.; Briški, F. Biosorption of chromium, copper, nickel and zinc onto fungal pellets of Aspergillus niger 405 from aqueous solutions. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2000, 38, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, C. Biosorbent for heavy metals removal and their future. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binupriya, A.R.; Sathishkumar, M.; Swaminathan, K.; Jeong, E.S.; Yun, S.E.; Pattabi, S. Biosorption of metal ions from aqueous solution and electroplating industry wastewater by Aspergillus japonicus: Phytotoxicity studies. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2006, 77, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Ortiz, E.J.; Shakya, M.; Jain, R.; Rene, E.R.; van Hullebusch, E.D.; Lens, P.N. Sorption of zinc onto elemental selenium nanoparticles immobilized in Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21619–21630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, G.; Arica, M.Y. Amidoxime functionalized Trametes trogii pellets for removal of uranium (VI) from aqueous medium. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, 307, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.; Baldrian, P.; Hladíková, K.; Háková, M. Copper sorption by native and modified pellets of wood-rotting basidiomycetes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 32, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.Q.; Li, S.; Zhu, H.Y.; Jiang, R.; Yin, L.F. Biosorption of copper (II) from aqueous solution by mycelial pellets of Rhizopus oryzae. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faryal, R.; Lodhi, A.; Hameed, A. Isolation, characterization and biosorption of zinc by indigenous fungal strains Aspergillus fumigatus RH05 and Aspergillus flavus RH07. Pak. J. Bot. 2006, 38, 817. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, M.; Malik, A. Simultaneous bioaccumulation of multiple metals from electroplating effluent using Aspergillus lentulus. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4991–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Cao, T.T.; Li, F.Y.; Cui, C.W. The comparison of biosorption characteristics between the two forms of Aspergillus niger strain. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 63, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, S.; Asma, D.; Erdemoglu, S.; Yesilada, O. Biosorption of copper (II) by live and dried biomass of the white rot fungi Phanerochaete chrysosporium and Funalia trogii. Eng. Life Sci. 2005, 5, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Cheng, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X. Novel fungus-Fe3O4 bio-nanocomposites as high performance adsorbents for the removal of radionuclides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 295, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rome, L.; Gadd, G.M. Use of pelleted and immobilized yeast and fungal biomass for heavy metal and radionuclide recovery. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1991, 7, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakshirajan, K.; Izquierdo, M.; Lens, P.N. Arsenic (III) removal at low concentrations by biosorption using Phanerochaete chrysosporium pellets. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, S.; Liu, G.; Liao, X.; Deng, X.; Sun, D.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y. Simultaneous biosorption of cadmium (II) and lead (II) ions by pretreated biomass of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2004, 34, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Q.B. Biosorption of lead by Phanerochaete chrysosporium in the form of pellets. J. Environ. Sci. 2002, 14, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yetis, U.; Dolek, A.; Dilek, F.B.; Ozcengiz, G. The removal of Pb (II) by Phanerochaete chrysosporim. Water Res. 2000, 34, 4090–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, C.; Yu, J. Copper adsorption and removal from water by living mycelium of white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Water Res. 1998, 32, 2746–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, J.; Kofroňová, O.; Rychlovský, P.; Krenželok, M. Accumulation and effect of cadmium in the wood-rotting basidiomycete Daedalea quercina. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1996, 57, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, A.; Zahid, S. Ni (II) biosorption by Rhizopus arrhizus Env 3: The study of important parameters in biomass biosorption. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2008, 83, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogej, A.; Pavko, A. Mathematical model of lead biosorption by Rhizopus nigricans pellets in a laboratory batch stirred tank. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2004, 18, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kogej, A.; Pavko, A. Laboratory experiments of lead biosorption by self-immobilized Rhizopus nigricans pellets in the batch stirred tank reactor and the packed bed column. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2001, 15, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, G.; Hernáinz, F.; Calero, M.; Martín-Lara, M.A.; Tenorio, G. The effect of pH on the biosorption of Cr (III) and Cr (VI) with olive stone. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 148, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepher, M.N.; Nasseri, S.; Zarrabi, M.; Samarghandi, M.R.; Amrane, A. Removal of Cr (III) from tanning effluent by Aspergillus niger in airlift bioreactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 96, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, Z. Equilibrium and kinetic modelling of cadmium (II) biosorption by Chlorella vulgaris in a batch system: Effect of temperature. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2001, 21, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binupriya, A.R.; Sathishkumar, M.; Kavitha, D.; Swaminathan, K.; Yun, S.E.; Mun, S.P. Experimental and isothermal studies on sorption of Congo red by modified mycelial biomass of wood-rotting fungus. CLEAN-Soil Air Water 2007, 35, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.; Zhang, S.; Pan, B.; Zhang, W.; Lv, L.; Zhang, Q. Heavy metal removal from water/wastewater by nanosized metal oxides: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 211, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Narbad, A.; Chen, W. Dietary strategies for the treatment of cadmium and lead toxicity. Nutrients 2015, 7, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luevano, J.; Damodaran, C. A review of molecular events of cadmium-induced carcinogenesis. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2014, 33, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rice, K.M.; Walker, E.M., Jr.; Wu, M.; Gillette, C.; Blough, E.R. Environmental mercury and its toxic effects. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2014, 47, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaymon, A.H.; Mohammed, A.A.; Al-Musawi, T.J. Removal of lead, cadmium, copper, and arsenic ions using biosorption: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013, 51, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaneya, O.; Santoshkumar, M.; Anand, S.N.; Karegoudar, T.B. Biosorption of acid violet dye from aqueous solutions using native biomass a new isolate of Penicillium sp. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2009, 63, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Chauhan, G.; Jain, A.K.; Sharma, S.K. Adsorptive potential of agricultural wastes for removal of dyes from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgacs, E.; Cserhati, T.; Oros, G. Removal of synthetic dyes from wastewater: A review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yang, F.; Yang, G.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D. Removal of azo dye from aqueous solution by a new biosorbent prepared with Aspergillus nidulans cultured in tobacco wastewater. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2013, 44, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilada, O.; Yildrim, S.C.; Birhanli, E.; Apohan, E.; Asma, D.; Kuru, F. The evaluation of pre-grown mycelial pellets in decolorization of textile dyes during repeated batch process. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalakshmi, S.; Muthuchelian, K.; Swaminathan, K. Kinetic and equilibrium studies on biosorption of reactive orange 107 dye from aqueous solution by native and treated fungus Alternaria Raphani. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2011, 3, 337–347. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Suresh, S. Kinetic and equilibrium studies on the biosorption of reactive black 5 dye bye Aspergillus foetidus. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, P.; Mishra, A.; Malik, A.; Pant, K.K. Biosorption of textile dye by Aspergillus lentulus pellets: Process optimization and cyclic removal in aerated bioreactor. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Malik, A. Comparative performance evaluation of Aspergillus lentulus for dye removal through bioaccumulation and biosorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2882–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Malik, A. Alkali, thermo and halo tolerant fungal isolate for the removal of textile dyes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 81, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, E.J.R.; Corso, C.R. Comparative study of toxicity of azo dye Procion Red MX-5B following biosorption and biodegradation treatments with the fungi Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus terreus. Chemosphere 2014, 112, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, C.R.; De Almeida, A.C.M. Bioremediation of dyes in textile effluents by Aspergillus oryzae. Microb. Ecol. 2009, 57, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdal, S.; Taskin, M. Uptake of textile dye Reactive Black-5 by Penicillium chrysogenum MT-6 isolated from cement-contaminated soil. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 4, 618–625. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.J.; Yang, M.; Yang, Q.X.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, B.P.; Pan, F. Biosorption of reactive dyes by the mycelium pellets of a new isolate of Penicillium oxalicum. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003, 25, 1479–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Chen, G.; Zheng, W. Bioaccumulation of Cu-complex reactive dye bye growing pellets of Penicillium oxalicum and its mechanism. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3565–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cing, S.D.E.O.; Hamamci, D.A.; Apohan, E.; Yeşilada, O. Decolorization of textile dyeing wastewater by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Folia Microbiol. 2003, 48, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binupriya, A.R.; Sathishkumar, M.; Swaminathan, K.; Kuz, C.S.; Yun, S.E. Comparative studies on removal of Congo red by native and modified mycelial pellets of Trametes versicolor in various reactor modes. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Aslam, H.; Liu, C.; Chen, S. A feasible method for growing fungal pellets in a column reactor inoculated with mycelium fragments and their application for dye accumulation from aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 105, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilada, O.; Cing, S.; Asma, D. Decolourisation of the textile dye Astrazon Ref FBL by Funalia trogii pellets. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 81, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, L.G.C.; Mashhadi, N.; Chen, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Taylor, K.E.; Biswas, N. A short review of techniques for phenol removal from wastewater. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2016, 2, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, N.S.; Boddu, V.M.; Krishnaiah, A. Biosorption of phenolic compounds by Trametes versicolor polyporus fungus. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2009, 27, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denizli, A.; Cihangir, N.; Rad, A.Y.; Taner, M.; Alsancak, G. Removal of chlorophenols from synthetic solutions using Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 2025–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.R.; Viraraghavan, T. Biosorption of phenol from an aqueous solution by Aspergillus niger biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 85, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M.; Sharma, D.K. Adsorption of phenols from wastewater. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 287, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, R.L.; Wu, F.C.; Juang, R.S. Liquid-phase adsorption of dyes and phenols using pinewood-based activated carbons. Carbon 2003, 41, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daifullah, A.A.M.; Girgis, B.S. Removal of some substituted phenols bye activated carbon obtained from agricultural waste. Water Res. 1998, 32, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramoğlu, G.; Gursel, I.; Tunali, Y.; Arica, M.Y. Biosorption of phenol and 2-chlorophenol by Funalia trogii pellets. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2685–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bosso, L.; Lacatena, F.; Cristinzio, G.; Cea, M.; Diez, M.C.; Rubilar, O. Biosorption of pentachlorophenol by Anthracophyllum discolor in the form of live fungal pellets. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathialagan, T.; Viraraghavan, T. Biosorption of pentachlorophenol from aqueous solutions by a fungal biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubilar, O.; Tortella, G.R.; Cuevas, R.; Cea, M.; Rodríguez-Couto, S.; Diez, M.C. Adsorptive removal of pentachlorophenol by Anthracophyllum discolor in a fixed-bed column reactor. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2012, 223, 2463–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, V.; Felinger, A.; Hegedűsova, A.; Dékány, I.; Pernyeszi, T. Comparative study of the kinetics and equilibrium of phenol biosorption on immobilized white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium from aqueous solution. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 103, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pernyeszi, T.; Honfi, K.; Boros, B.; Talos, K.; Kilár, F.; Majdik, C. Biosorption of phenol from aqueous solutions by fungal biomass of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Studia Univ. Babes-Bolyai Chem. 2009, 54, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Hai, F.I.; Yang, S.; Kang, J.; Leusch, F.D.; Roddick, F.; Price, W.E.; Nghiem, L.D. Removal of pharmaceuticals, steroid hormones, phytoestrogens, UV-filters, industrial chemicals and pesticides by Trametes versicolor: Role of biosorption and biodegradation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 88, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, D.; Jin, H.; Yu, L.; Hu, S. Deriving freshwater quality criteria for 2,4-dichlorophenol for protection of aquatic life in China. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 122, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calace, N.; Nardi, E.; Petronio, B.M.; Pietroletti, M. Adsorption of phenols by papermill sludges. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 118, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, H.Q. Biosorption of 2, 4-dichlorophenol from aqueous solution by Phanerochaete chrysosporium biomass: Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yu, H.Q. Biosorption of phenol and chlorophenols from aqueous solutions by fungal mycelia. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliom, R.J. Pesticides in the hydrologic system-what do we know and what´s next? Hydrol. Process. 2001, 15, 3197–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, G.M.; de Souza, C.G.M.; de Araújo, C.A.V.; Bona, E.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Castoldi, R.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M. Biosorption of herbicide picloram from aqueous solutions by live and heat-treated biomasses of Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst and Trametes sp. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 215, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Pan, C. Residue dynamics of clopyralid and picloram in rape plant rapeseed and field soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 86, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, A.G.; Airoldi, C. Toxic effect caused on microflora of soil by pesticide picloram application. J. Environ. Monit. 2001, 3, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA. Picloram—Herbicide Information Profile; Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Wang, B.; Hu, Y. Biosorption of humic acid by Aspergillus fumigatus mycelial pellets cultured under different conditions. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Chengdu, China, 18–20 June 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.L.; Banks, C.J. Mechanism of humic acid colour removal from natural waters by fungal biomass biosorption. Chemosphere 1993, 27, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, M.; Domanovac, T.; Briki, F. Removal of humic substances by biosorption. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi-Marshall, E.J.; Royer, T.V. Pharmaceutical compounds and ecosystem function: An emerging research challenge for aquatic ecologists. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, D.; Castellet-Rovira, F.; Villagrasa, M.; Badia-Fabregat, M.; Barceló, D.; Vicent, T.; Caminal, G.; Sarrà, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S. The role of sorption processes in the removal of pharmaceuticals by fungal treatment of wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610, 1147–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadou, I.A.; Sánchez-Vázquez, R.; Molina, R.; Martínez, F.; Melero, J.A.; Bautista, L.F.; Iglesias, J.; Morales, G. Biological removal of pharmaceutical compounds using white-rot fungi with concomitant FAME production of the residual biomass. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Urase, T.; Kusakabe, O. Biodegradation characteristics of pharmaceutical substances by whole fungal culture Trametes versicolor and its laccase. J. Water Environ. Technol. 2010, 8, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bottoni, P.; Caroli, S.; Caracciolo, A.B. Pharmaceuticals as priority water contaminants. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2010, 92, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.B.; Hai, F.I.; Singh, L.; Price, W.E.; Nghiem, L.D. Degradation of pharmaceuticals and personal care products by white-rot fungi—A critical review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2017, 3, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marco-Urrea, E.; Pérez-Trujillo, M.; Vicent, T.; Caminal, G. Ability of White-rot fungi to remove selected pharmaceuticals and identification of degradation products of ibuprofen by Trametes versicolor. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Geissen, S.U. In vitro degradation of carbamazepine and diclofenac by crude lignin peroxidase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 176, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, D.; Badia-Fabregat, M.; Vicent, T.; Caminal, G.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Balcázar, J.L.; Barceló, D. Fungal treatment for the removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in veterinary hospital wastewater. Chemosphere 2016, 152, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroune, L.; Saibi, S.; Bellenger, J.P.; Cabana, H. Evaluation of the efficiency of Trametes hirsuta for the removal of multiple pharmaceutical compounds under low concentrations relevant to the environment. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 171, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Aspergillus carbonarius | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 200 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (L): 1 g (ww); time: 10 h | 100 | qexp: 1.7 | Not reported | [58] |

| Aspergillus flavus | Zn | pH: 5; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 34 °C; diameter of pellets: 1–3 mm; time: 6 days | 100 | Not reported | 40.9 ± 0.7% | [60] |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 59.7 ± 0.5% | |||||

| Aspergillus lentulus | Cu(II) 1 | pH: 5; amount of pellets (L): 1.27–4.86 g·L−1 (dw) | 75–800 | qexp: 12.1–124.5 | 19.8–78.4% | [61] |

| pH: 2–8; amount of pellets (L): 1.71–4.89 g·L−1 (dw) | 80 | qexp: 1.7–15.2 | 3.6–79.8% | |||

| Cr(III) 1 | Amount of pellets (L): 4.03–4.64 g·L−1 (dw) | 1000–5000 | qexp: 171.0–331.5 | 26.0–79.4% | ||

| Ni(II) 1 | pH: 2–8; amount of pellets (L): 1.37–4.55 g·L−1 (dw) | 70–210 | qexp: 5.2–11.1 | 6.7–42.1% | ||

| 70 | qexp: 1.2–8.6 | 3.7–41.4% | ||||

| Pb(II) 1 | Amount of pellets (L): 0.46–4.67 g·L−1 (dw) | 500–4000 | qexp: 76.1–1120 | 12.9–71.0% | ||

| Aspergillus niger | Cu(II) | pH: 5.3; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 1 g·L−1 (ww); time: 2 h | 30 | qmax: 8.1 | Not reported | [62] |

| Aspergillus niger 405 | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 200 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets: 1 g (ww); diameter of pellets: 1–3 mm; time: 10 h | 10 | qmax: 5.7 | Not reported | [53] |

| Zn(II) | qmax: 4.7 | |||||

| Ni(II) | qmax: 14.1 | |||||

| CrO42- | qmax: 7.2 | |||||

| Aspergillus japonicus | Fe(II) | pH: 2–10; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 1 g (ww) | 25–100 | qmax: 1.3 | Not reported | [55] |

| Ni(II) | qmax: 1.2 | |||||

| Cr(VI) | qmax: 1.9 | |||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Aspergillus japonicus | Hg(II) | qmax: 1.2 | Not reported | [55] | ||

| Industrial wastewater | pH: 2.1; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets: 2.25 g (ww) | Ni(II): 44 Cr(VI): 90 | Ni(II): qmax: 1.16 Cr(VI): qmax: 2.57 | |||

| Funalia trogii | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 0.01 g·mL−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 3–5 mm; time: 30 min | 10–300 | qmax: 23.89 | 61% | [63] |

| Lentinus edodes | Hg(II) Cd(II) Zn(II) | pH: 6; agitation: 400 rpm; T: 25 C, amount of pellets (L, A): 1 g·L−1 (ww); time: 2 h | 25–600 | (L): Hg(II) qmax: 358.1 Cd(II) qmax: 86.4 Zn(II) qmax: 37.7 | Not reported | [52] |

| (A): Hg(II) qmax: 419.1 Cd(II) qmax: 299.4 Zn(II) qmax: 63.3 | ||||||

| Penicillium sp. | Sr(II) Th(IV) U(VI) | pH: 5 for Sr(II) and U(VI); 3 for Th(IV); continuously stirred; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L, nFe3O4-pellets): 0.2 g·L−1; time: 48 h | Sr(II): 1–30 Th(IV): 1–130 U(VI): 1–130 | (L): Sr(II) qmax: 93.3 Th(II) qmax: 250.8 U(VI) qmax: 205.2 | Sr (II), pH 8: 100% Th(IV), pH 5: 100% U(VI), pH 7: 100% | [64] |

| Fe3O4-pellets: Sr(II) qmax: 109.9 Th(II) qmax: 280.8 U(VI) qmax: 223.9 | ||||||

| Penicillium chrysogenum | Cs | pH: 5; air lift column system; liquid to solid ratio (v/v): 10:1; diameter of pellets: 5 mm; time: 3 h | Cs: 13.3 | qmax: 119 | 50% | [65] |

| Sr | Sr: 8.8 | qmax: 92 | 39% | |||

| U | U: 23.8 | qmax: 147 | 62% | |||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | As(III) | pH: 4; agitation: 150 rpm; ambient room T; amount of pellets (L): 0.25–1.5 g·L−1 (ww); time: 24 h | 0.2–1 | qmax: 5.5 | Not reported | [66] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Zn | pH: 4.5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L, nSe0-pellets): 3.2 g·L−1 (ww); time: 24 h | 10–50 | (L): qmax: 1.9–8.3 | (L): 56.2 ± 2.8% | [56] |

| (nSe0-pellets): qmax: 2.8–11.3 | (nSe0-pellets): 88.1 ± 5.3% | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cu(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets: 0.01 g·mL−1 (ww); time: 30 min | 10–300 | qmax: 18.2 | 50% | [63] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cd(II) | pH: 4.5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 27 °C; amount of pellets (D): 0.1 g (dw); diameter of pellets: 1.58–2.03 mm; time: 18 h | 10–450 | qmax: 15.2 | Not reported | [67] |

| Pb(II) | 10–450 | qmax: 12.3 | ||||

| Binary system: Pb(II), Cd(II) | Cd(II): 10–450; Pb(II): 25–50 | Cd(II) qmax: 10–8.9 | ||||

| Pb(II): 10–450; Cd(II): 25–50 | Pb(II) qmax: 8.2–4.5 | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | pH: 5.5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 27 °C; amount of pellets (L, Al. P): 2 g·L−1 (dw); diameter of pellets: 1.5–1.7 mm; time: 16 h | 50 | (L): qexp: 16.1 | 64.3% | [68] |

| (Al. P): qexp: 15.2–23.7 qmax: 144 | 60.6–94.7% | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | pH: 3–4; agitation: 200 rpm; T: 35 °C; amount of pellets (L, D): 90 mg (dw); time: 4 h | 5–50 | (L): qmax: 9 | Not reported | [69] |

| (D): qmax: 20 | ||||||

| pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 25 °C; age of pellets (Ac. P, Al. P): 41, 168 h | 20 | (Ac. P): qmax: 12.8–13.8 | ||||

| (Al. P): qmax: 20.1–48.2 | ||||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cu(II) | pH: 6; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 25 °C; time: 4 h | 100 | qmax: 3.9 | Not reported | [70] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cd(II) | pH: 6.2; T: 28 °C; amount of pellets: 0.2 g·mL−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 0.2–2 cm; time: 2 h | 1124 | qexp: 84.5 | 34% | [71] |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | Cu(II) | Column experiments; pH: 3, 4; total column volume: 620 mL; flow rate: 1mL·min−1; amount of pellets (L): pH 3: 3.93 g (dw) pH 4: 3.37 g (dw) | 100 | pH: 3 qexp: 1.9 | Not reported | [58] |

| pH: 4 qexp: 7.9 | ||||||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Ni(II) | pH: 8; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 35 °C; amount of pellets (L, D, Al. P): 3 g (ww); time: 72 h | 500 | (L): qmax: 315.6 | Not reported | [72] |

| (D): qmax: 125.4 | ||||||

| (Al. P): qmax: 357.6 | ||||||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Cs | Air lift column system Liquid to solid ratio (v/v): 10:1 pH: 5; diameter of pellets: 5 mm; time: 3 h | Cs: 13.3 | qmax: 82 | 41% | [65] |

| Sr | Sr: 8.8 | qmax: 88 | >90% | |||

| U | U: 23.8 | qmax: 180 | 44% | |||

| Rhizopus nigricans | Pb(II) | Batch stirred tank Agitation: 300 rpm; amount of pellets: 25–200 g·L−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 2.5 ± 0.5 mm | 20–300 | qmax: 83.5 | Not reported | [73] |

| Rhizopus nigricans | Li | pH: 5; agitation: 125 rpm; T: 22 ± 1 °C; diameter of pellets: 2.5 mm; time: 24 h | 10–1000 | qmax: 183.9 | Not reported | [74] |

| Al(III) | qmax: 163.0 | |||||

| Fe(II) | qmax: 466.4 | |||||

| Fe(III) | qmax: 407.7 | |||||

| Ni(II) | qmax: 201.2 | |||||

| Cu(II) | qmax: 360.4 | |||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Rhizopus nigricans | Zn(II) | pH: 5; agitation: 125 rpm; T: 22 ± 1 °C; diameter of pellets: 2.5 mm; time: 24 h | 10–1000 | qmax: 235.1 | Not reported | [74] |

| Sr(II) | qmax: 278.0 | |||||

| Ag | qmax: 451.9 | |||||

| Cd(II) | qmax: 302.6 | |||||

| Pb(II) | qmax: 403.2 | |||||

| Rhizopus oryzae | Cu(II) | pH: 4; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 25–45 °C; amount of pellets (Al. P): 1 g (ww); diameter of pellets: 1–1.2 mm | 10–300 | qmax: 52.9–61.7 | [59] | |

| Trametes versicolor | Cd(II) | pH: 6.2; T: 28 °C; amount of pellets: 0.2 g·mL−1 (ww); diameter of pellets: 0.2–2 cm | 1124.1 | 109.5 | 43% | [71] |

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Pellet Pretreatment | Operational Conditions | Best Suited Pretreatment for Adsorption | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lentinus edodes | Hg(II) Cd(II) Zn(II) | Thermal treatment | Pellets were heated at 90 °C for 15 min. | Thermal treatment | [52] |

| Penicillium sp. | Sr(II) Th(IV) U(VI) | Addition of nanoparticles of Fe3O4 | ~0.1 g of nano-Fe3O4 particles were added into a spore suspension cultivated at 140 rpm, 30 °C for 36 h. The mixed solution was incubated for further 72 h. | Fe3O4 addition | [64] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Zn | Addition of nanoparticles of Se (nSe0) | Pellets were grown with Na2SeO3 (10 mg Se L−1), 150 rpm, pH 4.5, and 30 °C for 96 h. | nSe0 addition | [56] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Cd(II) | Chemical and thermal inactivation | Pellets were inactivated by formaldehyde cross-linking and subsequent boiling in alkaline conditions for 45 min. | Not compared | [67] |

| Pb(II) | |||||

| Binary system: Pb(II), Cd(II) | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | Alkali pretreatment | Pellets were soaked in NaOH 0.1 M for 40 min. | Alkali pretreatment | [68] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Pb(II) | Autoclaving | Pellets were autoclaved (121 °C, 20 min). | Alkali pretreatment | [69] |

| Alkali pretreatment | Pellets were suspended in NaOH 0.1 M for 1 h. | ||||

| Acid pretreatment | Pellets were washed with HClO4 5 × 10−3 M for 5–40 min. | ||||

| Rhizopus arrhizus | Ni(II) | Alkali pretreatment | Pellets were treated separately with NaOH 0.1 M or NaCl 0.1 M for 30 min. Living (untreated) biomass was tested as a blank. | None (living biomass was best suited for Ni adsorption) | [72] |

| Rhizopus oryzae | Cu(II) | Thermal and alkali pretreatment | Pellets were boiled in NaOH 0.2 M (1:10 w/w) for 15 min. | Not compared | [59] |

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Alternaria raphanin | Reactive Orange 107 | pH: 7; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 ± 2 °C; amount of pellets (L, A): 0.02 g·mL−1 (ww); time: 90, 105 min | 10–50 | (L): qexp: 8.8–21.5; qeq: 8.9–24.9 (A): qexp: 8.0–24.0; qeq: 10.8–27.7 | (L): ~47.9–80.4% (A): ~42.9–88.1% | [89] |

| Aspergillus foetidus | Reactive Black 5 | pH: 2.3; agitation 200 rpm; T: 30, 50 °C; amount of pellets (L, Al. P): 0.2 ± 0.05 g (ww) | 100 | (L): qmax: 65–76 | 67% | [90] |

| (Al. P): qmax: 92–106 | 97% | |||||

| Aspergillus lentulus | Acid Blue 120 | pH: 6.5; agitation 128 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L, A): 2 g·L−1 (dw) | 100 | (L): qmax: 101 | 91% | [91] |

| (A): qmax: 104.2 | ||||||

| pH: 6.5; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 0.75–3 g·L−1 (dw) | 100 | qexp: 33.9–58.2 | 38.7–98.3% | |||

| pH: 6.5; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30 °C; Amount of pellets (L): 2 g·L−1 | 100–900 | qexp: 54.6–210.7 | 46.9–96.3% | |||

| pH: 4–10; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 2 g·L−1 | 200 | qexp: 88.0–99.4 | 82.0–94.4% | |||

| pH: 6.5; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30–45 °C; amount of pellets (L): 2 g·L−1 | 200 | qexp: 94.7–99.4 | 90.0–95.6% | |||

| Aspergillus lentulus | Acid Blue 120 | pH: 6.5; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 2 g·L−1 (dw); time: 4, 5, 24 h | 100 | qmax: 181.8 | 96.7% | [92] |

| Acid Red 88 | qmax: 196.1 | 94.3% | ||||

| Pigment Orange 34 | qmax: 243.9 | 95.5% | ||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Aspergillus lentulus | Basic Blue 9 | pH: 6.5; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 2 g·L−1 (dw); time: 4, 5, 24 h | 30 | qmax: 30.7 | 21.8–35.4% | [92] |

| Basic Violet 10 | qmax: 13.9 | 54.9–90.9% | ||||

| Acid Navy Blue and Fast Red A | 100 | Not reported | 94.2% | |||

| Acid Navy Blue and Methylene Blue | 50 | Not reported | 70.1% | |||

| Aspergillus lentulus | Acid Violet 19 | pH: 6.5; agitation 180 rpm; T: 30 °C; inoculum: 5% spore suspension of 6.25·106 mL; time: 20 h, 50 h | 100 | Not reported | 49–70% | [93] |

| Acid Blue 120 | 99% | |||||

| Acid Blue 89 | 92–98% | |||||

| Acid Red 88 | 98–99% | |||||

| Pigment Orange 34 | 91–99% | |||||

| Acid Blue 120 | 100–900 | qexp: ~25–212 | 100% for all the tested concentrations | |||

| Aspergillus niger ZJUBE-1 | Congo Red | pH: 2–5; agitation 120 rpm; T: 28 °C amount of pellets (L): 4 g·L−1 (ww) diameter of pellets: 2–4 mm; time: 12 h | 25–300 | qexp: 14.6–152.0 qmax: 263.2 | 99% | [2] |

| Acid Blue 29 Acid Red 27 Amido Black 10 B Congo Red Eriochrome Black T Orange II Methyl Blue Naphthol Green | pH: 6; agitation 120 rpm; T: 28 °C; amount of pellets (L): 2 g·L−1(ww); diameter of pellets: 2–4 mm; time: 24 h | 50 | Not reported | Orange II: 77.6% All the other tested dyes: >94% | ||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Aspergillus niger ZJUBE-1 | Eriochrome Black T | Batch Reactor pH: 6; aeration: 1 L·min−1; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (L): 30 g (ww); diameter of pellets: 2–4 mm; time: 12 h | 50 | qmax: 322.6 | >90% | [2] |

| Aspergillus niger | Procion Red MX-5B | pH: 4; T: 30 ± 1 °C; time: 3 h | 0.2 | Not reported | ~30% | [94] |

| Aspergillus oryzae | Procion Violet Red H3R | pH: 2.5; amount of pellets (L, A): 3.7·10−4–4.5−3 g·mL−1; Time: 120 min | 62.5 | (L): qexp: 9.6–25.0 (A): qexp: 11.0–26.3 | Not reported | [95] |

| Procion Red HE7B | pH: 2.5; amount of pellets (L, A): 3.7−4–0.03 g·mL−1 Time: 120 min | 300 | (L): qexp: 9.6–20.2 (A): qexp: 9.6–32.4 | |||

| Funalia trogii | Astrazon Black | Repeated batch system: 5 cycles agitation 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; pellets (L, D); time: 24 h | 100 | Not reported | (L): 1rst–5th use: ~92–40% (D): 1rst–3rd use: ~76–40% | [88] |

| Penicillium chrysogenum MT-6 | Reactive Black 5 | pH: 5; agitation 150 rpm; T: 28 °C amount of pellets: 3.83 g·L−1 (ww) time: 100 h | 300 | Not reported | 89% | [96] |

| Penicillium chrysosporium | Astrazon Black | Repeated batch system: 5 cycles agitation 150 rpm; T: 30 °C pellets (L, D); time: 24 h | 100 | - | (L): 1rst–5th use: ~92–28% (D): 1rst–4th use: ~72–10% | [88] |

| Penicillium oxalicum | Reactive Blue 19 | pH: 2; agitation 150 rpm; T: 20 °C amount of pellets (L): 0.25 g (ww) diameter of pellets: 2 mm; time: 24 h | 100 | qmax: 160 | Reactive Blue 19: 60–91% | [97] |

| Reactive Red 241 | qmax: 122 | |||||

| Reactive Yellow 145 | qmax: 137 | |||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Penicillium oxalicum | Cu-Complex Reactive Dye Blue 21 | pH: 7; agitation 120 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L): 119 ± 3.9–129 ± 4.1 mg (dw); diameter of pellets: 3.83 mm; time: 48 h | 100–300 | qmax: 77.5 ± 3.2–336 ± 6.8 | 99.7–100% | [98] |

| Penicillium sp. | Acid Violet | pH: 5.7; agitation 150 rpm; T: 35 °C amount of pellets (L): 0.01 g·mL−1 (ww); time: 12 h | 30 | qmax: 5.9 | Not reported | [84] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Indigo dye and dyeing wastewater | Repeated batch system: 5 cycles; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (L, D): 0.0092 g·mL−1 | Not reported | Not reported | (L): 1rst–5th use: 94.9–88.3% (D): 1rst–5th use: 36.5–38.7% | [99] |

| Trametes versicolor | Astrazon Black | Repeated batch system: 5 cycles; agitation 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; pellets (L, D); time: 24 h | 100 | Not reported | (L): 1rst–5th use: ~92–20% (D): 1rst–4th use: ~62–28% | [88] |

| Trametes versicolor | Congo Red | Bubble reactor type; pH: 7; aeration: 100 cm·s−1; T: 30 °C inoculum: 106 spores·mL−1; amount of pellets (L, A, Ac. P, Al. P): 1 g; time: 90 min | 10–50 | (L): qexp: 10–42.4; qmax: 50.8 | Not reported | [100] |

| (A): qexp: 10–46.1; qmax: 51.8 | ||||||

| (Ac. P): qexp: 6.9–26.2; qmax: 42.2 | ||||||

| (Al. P): qexp: 6.1–22.4; qmax: 38.2 | ||||||

| Trametes versicolor | Congo Red | Rotating biological contactor T: 30 °C; inoculum: 1 mL fungal spore suspension (106 spores); pellets (L, A); time: 65 min | 10–50 | (L): qmax: 38.9 (A): qexp: 10.0–36.5; qmax: 41.49 | Not reported | [100] |

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

| Trametes versicolor | Congo Red | pH: 2–10; agitation 150 rpm; T: 27 ± 2 °C; amount of pellets (L, A, Ac. P, Al. P): 1 g/50 mL (ww); time: 90 min | 10–50 | (L): qexp: 10–44; qmax: 52.9 | 87.9–100% | [78] |

| (A): qexp: 10–47.7 | 95.4–100% | |||||

| (Ac. P): qmax: 44.1 | 48.0–66.7% | |||||

| (Al. P): qmax: 39.5 | 55.5–74.1% | |||||

| Trichoderma harzianum | Acid Brilliant Red B | pH: 3; agitation: 120 rpm; T: 30 °C; inoculum: 5% v/v spore suspension (A = 0.5/cm at 600 nm) pellets (G, L, D); time: 72 h | 100–400 | (G): qmax: 86.5 ± 7.4–365 ± 25.2 (L): qmax: 73.0 ± 2.9–183 ± 12.6 (D): qmax: 65.7 ± 7.1–136 ± 14.1 | Not reported | [101] |

| Trichoderma harzianum | Rhodamine 6G | pH: 8; agitation: 125 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (A): 0.02 g·mL−1 (ww); time: 90 min | 10–50 | qexp: 0.4–1.9 qmax: 3.5 | 87–77% | [13] |

| Erioglaucine | pH: 4; agitation: 125 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (A): 0.02 g·mL−1 (ww); time: 75 min | qexp: 0.4–1.9 qmax: 3.14 | 88–76% |

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracophyllum discolor | Pentachlorophenol | pH: 5–5.5; agitation: 120 rpm T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (L): 20 ± 0.2 mg (dw); time: 24 h | 5–10 | Not reported | >80% | [111] |

| Funalia trogii | Phenol | pH: 2–11; agitation: 100 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (L, A): 0.25–2 g·L−1; time: 6 h | 200 | (L): qmax: 132.6 (A): qmax: 132.6 | Not reported | [110] |

| 2-Chlorophenol | (L): qmax: 132.6 (A): qmax: 132.6 | |||||

| Penicillium oxalicum | Phenol | pH: 6; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; amount of pellets (A): 0.25 g (ww); time: 24 h | 10–100 | qmax: 0.01 | Not reported | [9] |

| p-Cresol | qmax: 0.02 | |||||

| Naphthol | qmax: 0.06 | |||||

| p-Toluidine | qmax: 0.03 | |||||

| 1-Naphthalenamine | qmax: 0.15 | |||||

| p-Toluenesulfonic acid | qmax: 0.01 | |||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Phenol | pH: 5.5; agitation: 4000 rpm T: 22.5 °C; amount of pellets (L): 0.3 g·L−1; time: 2 h | 25–100 | qmax: 2.8–13.5 qeq: 6.7 | Not reported | [114] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Phenol | pH: 5; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 22.5 ± 2.5 °C; amount of pellets (A): 5 g·L−1; time: 3 h | 12.5–50 | qmax: 0.09–0.19 qeq: 0.09–0.19 | Not reported | [115] |

| Trametes versicolor | Pentachlorophenol | pH: not reported; agitation: 70 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (D): 0.4 g·L−1; time: 24 h | 0.05 | Not reported | >60% | [116] |

| 4-Tert-butylphenol | 10 ± 14% | |||||

| Bisphenol A | 26 ± 5% | |||||

| 4-Tert-octophenol | >60% | |||||

| Benzophenone | 10 ± 2% | |||||

| Octocrylene | 27 ± 2% |

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Adsorption Capacity (mg·g−1) | Removal | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Humic acid | pH: 4; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 30 °C; age culture: 2–10 days; amount of pellets (L): 0.5 g (ww); time: 1 h | 24 ± 0.5 | 2 days-grown pellets: qexp: 6.8 | Not reported | [126] |

| 10 days-grown pellets: qexp: 9.0 | ||||||

| Ganoderma lucidum | Picloram | pH: 3.76; agitation: 150 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (L, A): 0.05 g (dw); time: 2 h | 2415 | (L): qeq: 6.6 (A): qeq: 7.9 | Not reported | [122] |

| Trametes sp. | (L): qeq: 5.6 (A): qeq: 6.0 | |||||

| Trametes versicolor | Acid clofibric | pH: not reported; agitation: 70 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets (D): 0.4 g·L−1; time: 24 h | 0.05 | Not reported | 15 ± 3% | [116] |

| Atrazine | 9 ± 1% | |||||

| Ametryn | 4 ± 8% |

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Removal | Ref. | ||

| Ganoderma lucidum | Carbamazepine | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; time: 6 days; under dark conditions; amount of pellets (A): 0.5 ± 0.1 g (dw) | 0.05–0.18 | 13 ± 1% | [137] | ||

| Diclofenac | 34 ± 3% | ||||||

| Iopromide | 18 ± 1% | ||||||

| Venlafaxine | 11 ± 1% | ||||||

| Ganoderma lucidum | Ibuprofen | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; age of culture: 7 days; amount of pellets (A): 2 g·L−1 (ww) | 10 | ~50% | [135] | ||

| Carbamazepine | ~10% | ||||||

| Clofibric acid | ~23% | ||||||

| Irpex lacteous | Carbamazepine | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; time: 6 days; under dark conditions; amount of pellets (A): 0.5 ± 0.1 g (dw) | 0.05–0.18 | 5 ± 1% | [137] | ||

| Diclofenac | 26 ± 3% | ||||||

| Iopromide | 5 ± 1% | ||||||

| Venlafaxine | 6 ± 1% | ||||||

| Irpex lacteous | Ibuprofen | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; age of culture: 7 days; amount of pellets (A): 2 g·L−1 (ww) | 10 | Not removed | [135] | ||

| Carbamazepine | ~20% | ||||||

| Clofibric acid | ~5% | ||||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Ibuprofen | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; age of culture: 7 days on malt extract medium; amount of pellets (A): 2 g·L−1 (ww) | 10 | Not removed | [135] | ||

| Carbamazepine | ~31% | ||||||

| Clofibric acid | ~26% | ||||||

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Ibuprofen | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; age of culture: 7 days on malt extract medium; amount of pellets (A): 2 g·L−1 (ww) | 10 | Not removed | [135] | ||

| Carbamazepine | ~8.5% | ||||||

| Clofibric acid | ~27% | ||||||

| Trametes hirsuta | 0.0001 | L: | A: | B: | [138] | ||

| Carbamazapine | ~36% | ~28% | - | ||||

| Acid clofibric | ~5% | 100% | ~60% | ||||

| Naproxen | 100% | ~90% | - | ||||

| Ketoprofen | 100% | ~12% | ~14% | ||||

| Ibuprofen | 100% | ~90% | ~75% | ||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Removal | Ref. | ||

| L: | A: | B: | |||||

| Trametes hirsuta | Indomethacin | 0.0001 | 100% | 100% | ~10% | [138] | |

| Acetaminophen | ~76% | ~30% | ~45% | ||||

| Fenofibrate | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||||

| Amoxicillin | 100% | ~30% | ~38% | ||||

| Ioperamide | ~24% | ~10% | ~10% | ||||

| Trametes versicolor | Carbamazepine | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; time: 6 days; under dark conditions; amount of pellets (A): 0.5 ± 0.1 g (dw) | 0.05–0.18 | 8 ± 1% | [137] | ||

| Diclofenac | 42 ± 12% | ||||||

| Iopromide | 8 ± 1% | ||||||

| Venlafaxine | 6 ± 1% | ||||||

| Trametes versicolor | Ibuprofen | Amount of pellets: 0.4 g·L−1 (ww) | 0.05 | 32 ± 1% | [116] | ||

| Gemfibrozil | >60% | ||||||

| Diclofenac | >60% | ||||||

| Triclosan | >60% | ||||||

| Ketoprofen | 10 ± 15% | ||||||

| Naproxen | 14 ± 5% | ||||||

| Carbamazepine | 6 ± 5% | ||||||

| Primidone | 24 ± 34% | ||||||

| Amitriptyline | 8 ± 8% | ||||||

| Trametes versicolor | Estriol | Amount of pellets: 0.4 g·L−1 (ww) | 0.05 | 13 ± 4% | [116] | ||

| Estrone | >60% | ||||||

| 17α-Ethinylestradiol | >60% | ||||||

| 17β-Estradiol | >60% | ||||||

| 17β-Estradiol-17acetate | >60% | ||||||

| Fungal Strain | Adsorbate | Operational Conditions | Adsorbate Concentration (mg·L−1) | Removal | Ref. | ||

| Trametes versicolor | Enterolactone | Amount of pellets: 0.4 g·L−1 (ww) | 0.05 | 3 ± 15% | [116] | ||

| Formononetin | 15 ± 5% | ||||||

| Trametes versicolor | Ibuprofen | Agitation: 135 rpm; T: 25 °C; amount of pellets: 2 g·L−1 (ww) | 10 | ~25% | [116] | ||

| Carbamazepine | ~10% | ||||||

| Clofibric acid | ~5% | ||||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Legorreta-Castañeda, A.J.; Lucho-Constantino, C.A.; Beltrán-Hernández, R.I.; Coronel-Olivares, C.; Vázquez-Rodríguez, G.A. Biosorption of Water Pollutants by Fungal Pellets. Water 2020, 12, 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041155

Legorreta-Castañeda AJ, Lucho-Constantino CA, Beltrán-Hernández RI, Coronel-Olivares C, Vázquez-Rodríguez GA. Biosorption of Water Pollutants by Fungal Pellets. Water. 2020; 12(4):1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041155

Chicago/Turabian StyleLegorreta-Castañeda, Adriana Jazmín, Carlos Alexander Lucho-Constantino, Rosa Icela Beltrán-Hernández, Claudia Coronel-Olivares, and Gabriela A. Vázquez-Rodríguez. 2020. "Biosorption of Water Pollutants by Fungal Pellets" Water 12, no. 4: 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041155

APA StyleLegorreta-Castañeda, A. J., Lucho-Constantino, C. A., Beltrán-Hernández, R. I., Coronel-Olivares, C., & Vázquez-Rodríguez, G. A. (2020). Biosorption of Water Pollutants by Fungal Pellets. Water, 12(4), 1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041155