eHealth and mHealth in Chronic Diseases—Identification of Barriers, Existing Solutions, and Promoters Based on a Survey of EU Stakeholders Involved in Regions4PerMed (H2020)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Purpose of the Study

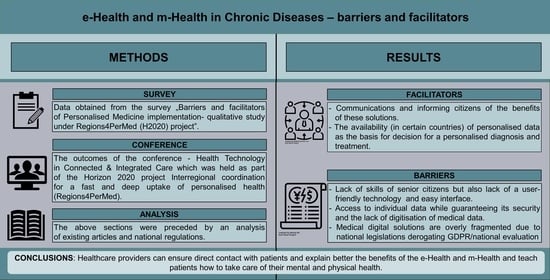

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

- Training for healthcare professionals: health technologies are often beneficial to patients, but health professionals often encounter difficulties in using the equipment associated with these technologies, which can increase the risk of accidents;

- Patient engagement: there is growing evidence that increased patient awareness leads to better care and treatment adherence, as well as improved health and well-being;

- Economic impact of health technologies: critical to the market access of health technologies and the implementation of personalised medicine is the valuation of health technologies, which needs to be discussed to assess market barriers and identify potential solutions [2].

3.2. Setting

3.3. Participants

3.4. Data Sources

3.5. Study Size

3.6. Variables

3.6.1. Quantitative Variables

3.6.2. Qualitative Variables

“In your opinion, what are the most important facilitators and barriers to public use of personalised medicine? What do the barriers/facilitators relate to (types of barriers identified, e.g., health care system, government, and PM users)? Please list and explain them briefly.”

3.7. Ethics Approval

4. Results

4.1. Systematic Reviews of Barriers and Facilitators of eHealth and mHealth

4.2. Participants and Descriptive Data—Survey

4.3. Participants and Descriptive Data—Conference

5. Discussion

5.1. Chronic Diseases Management

5.2. System for the Collection of Medical Data in Chronic Diseases

5.3. Use of eHealth and mHealth by Older People

5.4. Patient Engagement in eHealth and mHealth

5.5. eHealth and mHealth—Quality of Life

5.6. Integrated Care Policies

5.7. Healthcare Providers in Chronic Diseases

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moss, R.J.; Süle, A.; Kohl, S. eHealth and mHealth. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2019, 26, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zwiefka, A.; Kurpas, D.; Stefanicka-Wojtas, D.; Duda-Sikuła, M.; D’Errico, G. Regions4PerMed Report, Key Area 2: Health Technology in Connected & Integrated Care; HORIZON 2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Talboom-Kamp, E.P.; Verdijk, N.A.; Harmans, L.M.; Numans, M.E.; Chavannes, N.H. An eHealth Platform to Manage Chronic Disease in Primary Care: An Innovative Approach. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2016, 5, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The “mHealth Market 2021–2027” Report ResearchAndMarkets.com’s Offering. Dublin, 13 September 2021 (Globe Newswire). Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5411661/mhealth-market-by-component-mhealth-apps?utm_source=GNOM&utm_medium=PressRelease&utm_code=klmdlj&utm_campaign=1588547+-+Global+mHealth+Markets+Report+2021-2027+-+Market+Timelines+and+Technology+Roadmaps+Analysis&utm_exec=chdo54prd (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Foster, M.V.; Sethares, K.A. Facilitators and barriers to the adoption of telehealth in older adults: An integrative review. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2014, 32, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, A.W. mHealth—Opportunities for transforming global health care and barriers to adoption. J. Electron. Resour. Med. Libr. 2015, 12, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmeijer, R.; Pavlova, M.; Tambor, M.; Golinowska, S.; Groot, W. The use of e-health and m-health tools in health promotion and primary prevention among older adults: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16 (Suppl. 5), 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alwashmi, M.F.; Fitzpatrick, B.; Davis, E.; Gamble, J.M.; Farrell, J.; Hawboldt, J. Perceptions of Health Care Providers Regarding a Mobile Health Intervention to Manage Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Qualitative Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e13950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Heinsch, M.; Betts, D.; Booth, D.; Kay-Lambkin, F. Barriers and facilitators to the use of e-health by older adults: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenbos, G.A.; Peute, L.; Jaspers, M. Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: A literature based framework (MOLD-US). Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 114, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdie, F.; Woo, K. The use of mHealth technology for chronic disease management the challenges and opportunities for practical application. Wounds Int. 2020, 11, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cajita, M.I.; Hodgson, N.A.; Lam, K.W.; Yoo, S.; Han, H.R. Facilitators of and Barriers to mHealth Adoption in Older Adults with Heart Failure. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2018, 36, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenblum, R.; Jang, Y.; Zimlichman, E.; Salzberg, C.; Tamblyn, M.; Buckeridge, D.; Forster, A.; Bates, D.W.; Tamblyn, R. A qualitative study of Canada’s experience with the implementation of electronic health information technology. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2011, 183, E281–E288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Currie, M.; Philip, L.J.; Roberts, A. Attitudes towards the use and acceptance of eHealth technologies: A case study of older adults living with chronic pain and implications for rural healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imison, C.; Castle-Clarke, S.; Watson, R.; Edwards, N.; The Nuffield Trust. Delivering the Benefits of Digital Health Care. Available online: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/delivering-the-benefits-of-digital-technology-web-final.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Guo, Y.; Albright, D. The effectiveness of telehealth on self-management for older adults with a chronic condition: A comprehensive narrative review of the literature. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitelaw, S.; Pellegrini, M.D.; Mamas, M.A.; Cowie, M.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Barriers and facilitators of the uptake of digital health technology in cardiovascular care: A systematic scoping review. Eur. Heart J.-Digit. Health 2021, 2, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranha, M.; James, K.; Deasy, C.; Heavin, C. Exploring the barriers and facilitators which influence mHealth adoption among older adults: A literature review. Gerontechnology 2021, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.; Brown, R.; Sillence, E.; Coventry, L.; Lloyd, K.; Gibbs, J.; Tariq, S.; Durrant, A.C. Understanding the Barriers and Facilitators to Sharing Patient-Generated Health Data Using Digital Technology for People Living With Long-Term Health Conditions: A Narrative Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 641424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymberg, V.M.; Bolmsjö, B.B.; Wolff, M.; Calling, S.; Gerward, S.; Sandberg, M. Having to learn this so late in our lives… ‘Swedish elderly patients’ beliefs, experiences, attitudes and expectations of e-health in primary health care. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2019, 37, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ware, P.; Bartlett, S.J.; Paré, G.; Symeonidis, I.; Tannenbaum, C.; Bartlett, G.; Poissant, L.; Ahmed, S. Using eHealth Technologies: Interests, Preferences, and Concerns of Older Adults. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2017, 6, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zibrik, L.; Khan, S.; Bangar, N.; Stacy, E.; Novak Lauscher, H.; Ho, K. Patient and community centered eHealth: Exploring eHealth barriers and facilitators for chronic disease self-management within British Columbia’s immigrant Chinese and Punjabi seniors. Health Policy Technol. 2015, 4, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, P.; Wille, M.; Bröhl, C.; Theis, S.; Schäfer, K.; Knobe, M.; Mertens, A. Prevalence of health app use among older adults in Germany: National survey. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schreiweis, B.; Pobiruchin, M.; Strotbaum, V.; Suleder, J.; Wiesner, M.; Bergh, B. Barriers and Facilitators to the Implementation of eHealth Services: Systematic Literature Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wildenbos, G.A.; Peute, L.; Jaspers, M. Facilitators and barriers of electronic health record patient portal adoption by older adults: A literature study. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 235, 308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.; Gupta, N. Progress in electronic medical record adoption in Canada. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, S.D.; de Boer, K.; Nedeljkovic, M.; Meyer, D. Barriers and facilitators of videoconferencing psychotherapy implementation in veteran mental health care environments: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natsiavas, P.; Kakalou, C.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D.; Maglaveras, N.; Komnios, I.; Koutkias, V. Identification of Barriers and Facilitators for eHealth Acceptance: The KONFIDO Study. In Precision Medicine Powered by pHealth and Connected Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanicka-Wojtas, D.; Kurpas, D. Personalized medicine—Challenge for healthcare system: A perspective paper. Med. Sci. Pulse 2021, 15, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interregional Coordination For A Fast And Deep Uptake Of Personalised Medicine—Regions4PerMed, Best Practices Booklet, Key Area 1: Big Data Electronic Health Records and Health Governance. 2020. Available online: https://www.regions4permed.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/KA1_Best-Practices.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Stegemann, E.-M. Regions4PerMed Report, Key Area 3: Personalising Health Industry; HORIZON 2020; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Porzig, R.; Neugebauer, S.; Heckmann, T.; Adolf, D.; Kaskel, P.; Froster, U.G. Evaluation of a cancer patient navigation program (“Onkolotse”) in terms of hospitalization rates, resource use and healthcare costs: Rationale and design of a randomized, controlled study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maresova, P.; Javanmardi, E.; Barakovic, S.; Husic, J.B.; Tomsone, S.; Krejcar, O.; Kuca, K. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age—A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanicka-Wojtas, D.; Duda-Sikuła, M.; Kurpas, D. Personalised medicine—Best practices exchange and personal health implementation in European regions—A qualitative study concept under the Regions4PerMed (H2020) project. Med. Sci. Pulse 2020, 14, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamine, S.; Gerth-Guyette, E.; Faulx, D.; Green, B.B.; Ginsburg, A.S. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Triantafyllidis, A.; Kondylakis, H.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D.; Maglaveras, N.; Rahimi, K. Features, outcomes, and challenges in mobile health interventions for patients living with chronic diseases: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 132, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Zhao, Y. Mobile health technology: A novel tool in chronic disease management. Intell. Med. 2021, 2, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, S.; Ashall-Payne, L.; Andrews, T. Barriers and Facilitators to the Adoption of Mobile Health among Health Care Professionals from the United Kingdom: Discrete Choice Experiment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e17704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlovin, L.; Bonet, B.; Kambo, I. Using Digital Health Technology to Address Payer Concerns about Data Capture. Available online: https://www.crai.com/insights-events/publications/using-digital-health-technology-address-payer-concerns-about-data-capture/ (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Stuck, A.E.; Moser, A.; Morf, U.; Wirz, U.; Wyser, J.; Gillmann, G.; Born, S.; Dwahlen, M.; Iliffe, S.; Harari, D.; et al. Effect of health risk assessment and counselling on health behaviour and survival in older people: A pragmatic randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bujnowska-Fedak, M.M.; Pirogowicz, I. Support for e-health services among elderly primary care patients. Telemed. J. E Health 2014, 20, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaiser Permanente Research Brief: Diabetes. 2018. Available online: https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/content/dam/internet/kp/comms/import/uploads/2019/04/research_brief_diabetes_20180709.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Improving Patient Engagement through Mobile Health. Available online: https://www.aha.org/aha-center-health-innovation-market-scan/2019-07-15-improving-patient-engagement-through-mobile (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Lee, K.; Kwon, H.; Lee, B.; Lee, G.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.R.; Shin, S.-Y. Effect of self-monitoring on long-term patient engagement with mobile health applications. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Errico, G.; Cormio, P.G.; Bello, P.; Duda-Sikuła, M.; Zwiefka, A.; Krzyżanowski, D.; Stegemann, E.-M.; Allegue Requeijo, B.; Romero Fidalgo, J.M.; Kurpas, D. Interregional coordination for a fast and deep uptake of personalised health (Regions4Permed)—Multidisciplinary consortium under the H2020 project. Med. Sci. Pulse 2019, 13, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronic Diseases: E-Health and Chronically Ill Patient Management. Available online: https://www.ippocrateas.eu/chronic-diseases-ehealth-and-chronically-ill-patient-management/ (accessed on 25 September 2021).

| Barriers to eHealth and mHealth Implementation in Chronic Diseases | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | - lack of awareness of eHealth and mHealth services | [7,9,18,21,22,24,27] |

| - lack of experience and knowledge | [10,11,12,14,17,18,20,22,25] | |

| - lack of necessary equipment | [8,12,20,24] | |

| - lack of motivation | [10,20,23,24,25] | |

| - cost of new technology, lack of access to electronic devices | [7,8,9,12,17,20,24] | |

| - lack of or limited trainings | [7,9,17,21,26] | |

| Technological | - user-friendly technical tools | [7,9,10,12,14,18,22,23,24,28] |

| - safety precautions | [11,15,18,19,20,21,23,24,25,26,28] | |

| - poor/unreliable internet | [8,9,14,17] | |

| Organizations, policies, legislation | - lack of integrated care policies | [7,11,13,26] |

| - financial barriers: financial concerns, financial constraints | [8,17,20,22] | |

| - lack of trust between organizations, data sharing | [9,11,15,19,20,22,23,27,28] |

| Facilitating Factors for eHealth and mHealth Implementation in Chronic Diseases | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | - motivation to change lifestyle change, learning about health | [7,8,9,12,22,24] |

| - improving self-management skills, self-health monitoring | [7,8,14,15,16,17,19,21,23,24,25] | |

| - reducing the number of hospitalisations | [16,22] | |

| - eHealth and mHealth saving time | [7,20,22] | |

| - suport from family and/or caregivers | [17,18,22,23] | |

| - increase in physical activity and mental stimulation | [16,22] | |

| - improved connection and communication with physician | [7,8,11,15,16,17,20] | |

| Technological | - globally standardised coding schemes | [28] |

| - easy to use eHealth software | [8,12,17,22,24,27] | |

| - ability to use eHealth applications via mobile devices | [20,22,26] | |

| Organizations, policies, legislation | - implementation of international legislation, e.g., GDRP and Directive 95/46/EC | [28] |

| Quadruple Aim | Barriers for the Implementation of Personalised Medicine Interventions | Facilitators of the Implementation of Personalised Medicine Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| improving the individual experience of care |

|

|

| improving the health of populations |

|

|

| reducing the per capita cost of healthcare |

|

|

| improving the experience of providing care (the importance of physicians, nurses and all employees finding joy and meaning in their work) |

|

|

| Project Initiative Title | Country | Key National Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Return of genomic data to biobank participants, personalised medicine pilot projects in Estonia | Estonia | The aim of the pilot projects supported by the Estonian Research Agency RITA: development and gradual implementation of the rules, procedures, and principles necessary for the introduction of personalised medicine for general practitioners and specialists. During the project, more than 2000 biobank participants received genetic feedback and were further researched and treated by primary care physicians, oncologists, and medical geneticists as needed. Project website: https://genomics.ut.ee/en (accessed on 19 February 2022) [30] |

| Onkolotse (Cancer guide) | Germany | Improve personal support for cancer patients and their families along the treatment pathway and across all medical settings (idea: one face to the patient). Onkolotse will help patients and their families to find their personal path through cancer treatment, become informed patients, improve treatment adherence and coping, and help them live with the disease and make the most of their lives. Project website: www.nweurope.eu/codex4smes (accessed on 19 February 2022) [31,32] |

| How the Techforlife cluster can support and improve Lombardy’s healthcare system | Italy | The main challenge is to use technology to provide a high standard of care in the daily lives of people with chronic diseases; in particular, ensuring a personalised motor and cognitive rehabilitation process while improving the quality of life of patients. The goal is to focus on the monitoring and safety of patients in their homes, to create technological innovation through a high-level scientific approach that is fostered by multidisciplinarity and technology transfer, including the implementation of efficient business models. Project website: https://cluster.techforlife.it (accessed on 19 February 2022) [30] |

| Organisational and digital development in the care of chronically ill patients | Italy | ASST Vimercate has a defined process that enables the proactive “care” of chronic and frail patients, including the definition of different professional roles, the introduction of an outsourced service centre to manage care activities, the introduction of the role of “case manager” to ensure the quality of the process and care. In addition, ASST Vimercate has begun to use “Big Data Analytics” technologies to develop predictive algorithms that help professionals in the early detection of patients with certain chronic diseases and the occurrence of complications. Project website: https://www.asst-brianza.it/web/ (accessed on 19 February 2022) [30] |

| Virtual coach and chatbot interactions for cognitive enhancement | Italy | The main challenge is to provide outcome-based integrated care to older people to improve their quality of life and that of their families, while making European health and social care systems more sustainable, and to build an integrated care system between health and social services by proposing an app-based platform that connects informal and formal caregivers and supports with health empowerment through a virtual coach. Project website: https://www.israa.it/home-europa (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| BIOCAM—AI approach to doctor’s workload reduction | Poland | BIOCAM is a start-up company developing innovative capsule endoscopy that enhances patients’ comfort of life and provides new healthcare solutions. The most common diseases that can be screened with capsule endoscopy are Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, small bowel tumors, and anemia of unexplained cause. The endoscopy capsule is only 11 mm wide and 23 mm long. Project website: https://biocam.pl/ (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| Cardiomatis | Poland | The cloud tool speeds diagnosis and increases efficiency for cardiologists, clinicians, and other healthcare professionals in interpreting ECGs, automating the detection and analysis of about 20 cardiac abnormalities. The software integrates with more than 25 ECG monitoring devices and offers an advanced cloud software interface as a differentiator from traditional medical software. Project website: https://cardiomatics.com/ (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| Glucoactive—control diabetes, everywhere, always | Poland | Innovative technology enables non-invasive, automatic measurement of blood glucose levels. The proposed telemedicine solutions, including online storage, enable fast and accurate measurement, as well as features known from premium-class smartwatches. The devices have no replaceable elements such as strips or sensors, they are a one-time purchase, which means cost savings compared to invasive devices. Project website: www.gluco-active.com (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| Infermedica | Poland | Infermedica is developing its diagnostic engine to collect admissions, verify symptoms, and guide patients to the right treatment. The company uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to evaluate symptoms and find patterns in the data. The medical team reviews every piece of information added to the medical database to ensure patients receive safe and reliable recommendations. Infermedica develops mobile, web, and chatbot apps that are easy to use and integrate. Project website: https://infermedica.com/ (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| Patient Rescue Support Project Wrist-Band Device | Poland | The aim is to develop an innovative care concept tailored to solving the problems associated with demographic change. The wrist-band device can work in two ways: 1. It collects basic data (real-time physiological signals) on the wrist to help a person with frailty, without having to call the emergency services. The data from the wristband ID is transmitted to the dispatcher; 2. It can give doctors and medical staff access to clinic data. Project website: http://www.wrp.info.pl (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| StethoMe® | Poland | The company has developed an intelligent solution to improve diagnosis in primary care. StethoME is an AI-powered healthcare solution that enables automated and remote lung and heart exams. It provides the telemedicine solution with the missing piece of the puzzle of remote interaction between the professional, the physician, and the patients themselves. Project website: https://stethome.com/ (accessed on 19 February 2022) [2] |

| HAITool—A real-time hospital infection surveillance and hospital-wide intelligent clinical decision support system | Portugal | To solve the problem of multiple sources of hospital/patient data, a web-based information system was developed that supports an SQL server that extracts and summarises patient data, microbiology laboratory results, and pharmacy data. Data are extracted at regular intervals from hospitals’ existing information systems by an ExtracteTransformationeLoad (ETL) module, using intelligent automated routines and then being processed and aggregated in a single data warehouse. Project website: http://www.haitool.ihmt.unl.pt (accessed on 19 February 2022) [30] |

| NAGEN 1000: An example of a project for regional implementation of personalized genomic medicine in healthcare | Spain | “NAGEN 1000” is a pilot study to integrate recent advances in modern genomic technology into clinical practice. The study mainly targets patients with rare diseases and their families. The whole-genome data provide answers not only for rare diseases, but also for the field of personalised prevention by analysing genetic factors associated with the risk of serious, preventable diseases. In addition, the analysis of pharmacogenomic variants provides initial insights into the type and dosage of certain drugs that are tolerated by individuals. Project website: https://www.nagen1000navarra.es (accessed on 19 February 2022) [30] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stefanicka-Wojtas, D.; Kurpas, D. eHealth and mHealth in Chronic Diseases—Identification of Barriers, Existing Solutions, and Promoters Based on a Survey of EU Stakeholders Involved in Regions4PerMed (H2020). J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030467

Stefanicka-Wojtas D, Kurpas D. eHealth and mHealth in Chronic Diseases—Identification of Barriers, Existing Solutions, and Promoters Based on a Survey of EU Stakeholders Involved in Regions4PerMed (H2020). Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(3):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030467

Chicago/Turabian StyleStefanicka-Wojtas, Dorota, and Donata Kurpas. 2022. "eHealth and mHealth in Chronic Diseases—Identification of Barriers, Existing Solutions, and Promoters Based on a Survey of EU Stakeholders Involved in Regions4PerMed (H2020)" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 3: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030467

APA StyleStefanicka-Wojtas, D., & Kurpas, D. (2022). eHealth and mHealth in Chronic Diseases—Identification of Barriers, Existing Solutions, and Promoters Based on a Survey of EU Stakeholders Involved in Regions4PerMed (H2020). Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(3), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12030467