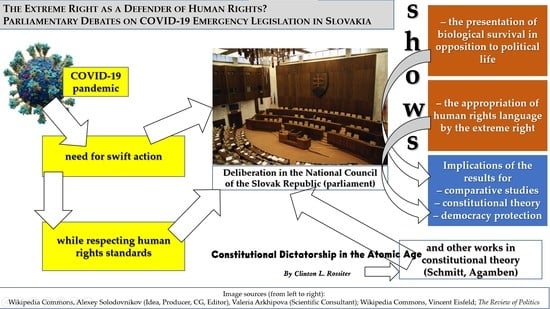

The Extreme Right as a Defender of Human Rights? Parliamentary Debates on COVID-19 Emergency Legislation in Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. States of Emergency and Human Rights: A Trade-Off between Life and Survival?

3. The Case of Slovakia: No Country for Weepers

4. Methodology: Analyzing Parliamentary Discourse on Emergency Bills

5. Results: The Extreme Right as a Champion of Human Rights Language?

5.1. Safety above Rights, Survival above Life?

5.2. Rights Talk and the Extreme Right

5.3. ‘Outsourcing’ Rights Restrictions?

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2002. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2003. Prostředky bez účelu: Poznámky o politice. Praha: SLON. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. State of Exception. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bächtiger, André. 2016. Debate and Deliberation in Legislatures. In The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies. Edited by Shane Martin, Thomas Saalfeld and Kaare W. Strom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 145–66. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, Susanne. 2020. Who Cares? A Defence of Judicial Review. Journal of the British Academy 8: 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, Elisabeth, and Nick Sitter. 2020. The EU’s Enfants Terribles: Democratic Backsliding in Central Europe since 2010. Perspectives on Politics, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balog, Boris. 2021. Ochrana základných práv v skrátenom legislatívnom konaní. In Ústavné orgány a ústavná ochrana základných práv vo krízových situáciách. Bratislava: Právnická fakulta UK, pp. 7–14. Available online: https://www.flaw.uniba.sk/fileadmin/praf/Veda/Konferencie_a_podujatia/BPF/2021/Zbornik_BPF_2021_sekcia_5_Ustavne_pravo_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Bar-Siman-Tov, Ittai. 2020. COVID-19 Meets Politics: The Novel Coronavirus as a Novel Challenge for Legislatures. The Theory and Practice of Legislation 8: 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, Paul. 2004. Introduction: The Whys and Wherefores of Analysing Parliamentary Discourse. In Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Parliamentary Discourse. Edited by Paul Bayley. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Beblavý, Miroslav. 2020. How Slovakia Flattened the Curve. Foreign Policy. May 6. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/06/slovakia-coronavirus-pandemic-public-trust-media/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Berdisová, Lucia. 2020a. Ako sme zvládli núdzový stav? Lekárske noviny 6: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Berdisová, Lucia. 2020b. Parlamentná kultúra a rokovanie o Správe o činnosti verejnej ochrankyne práv za rok 2019. In Parlamentná kultúra. Edited by Jakub Neumann. Trnava: Typi Universitatis Tyrnavaiensis, pp. 30–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bolleyer, Nicole, and Orsolya Salát. 2021. Parliaments in Times of Crisis: COVID-19, Populism and Executive Dominance. West European Politics 44: 1103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buštíková, Lenka, and Pavol Baboš. 2020. Best in Covid: Populists in the Time of Pandemic. Politics and Governance 8: 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Rafael A., Sebastian Deterding, and Richard M. Ryan. 2020. Health Surveillance during Covid-19 Pandemic. BMJ 369: m1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cormacain, Ronan, and Ittai Bar-Siman-Tov. 2020. Legislatures in the Time of Covid-19. The Theory and Practice of Legislation 8: 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csernatoni, Raluca. 2020. New States of Emergency: Normalizing Techno-Surveillance in the Time of COVID-19. Global Affairs 6: 301–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, James, and Seán Hanley. 2016. The Fading Mirage of the ‘Liberal Consensus’. Journal of Democracy 27: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denník N. 2020. Štátny tajomník Martin Klus k repatriácii Slovákov zo zahraničia. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/projektn.sk/videos/901690976945941/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Douglas, Jeremy. 2009. Disappearing Citizenship: Surveillance and the State of Exception. Surveillance & Society 6: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinóczi, Tímea, and Agnieszka Bień-Kacała. 2020. COVID-19 in Hungary and Poland: Extraordinary Situation and Illiberal Constitutionalism. The Theory and Practice of Legislation 8: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECRI. 2020. Sixth Report on Slovakia. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/european-commission-against-racism-and-intolerance/slovak-republic (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission). 2020. Compilation of Venice Commission Opinions and Reports on States of Emergency. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16809e38a6 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Ferejohn, John, and Pasquale Pasquino. 2004. The Law of the Exception: A Typology of Emergency Powers. International Journal of Constitutional Law 2: 210–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gál, Zsolt, and Darina Malová. 2021. Slovakia in the Eurozone: Tatra Tiger or Mafia State inside the Elite Club? In The Political Economy of the Eurozone in Central and Eastern Europe: Why In, Why Out? Edited by Krisztina Arató, Boglarka Koller and Anita Pelle. London: Routledge, pp. 165–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gál, Zsolt, and Soňa Szomolányi. 2016. Slovakia’s Elite: Between Populism and Compliance with EU Elites. In The Visegrad Countries in Crisis. Edited by Jan Pakulski. Warsaw: Collegium Civitas, pp. 66–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrerová, Ria. 2020a. Nariadenie, ktorým polícia uzavrela hranice, zrejme neexistuje, povinná štátna karanténa môže byť protiústavná. Denník N. May 5. Available online: https://dennikn.sk/1882207/nariadenie-ktorym-policia-uzavrela-hranice-zrejme-neexistuje-povinna-statna-karantena-moze-byt-protiustavna/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Gehrerová, Ria. 2020b. Keď chcú byť spolu, majú jedinú možnosť: Uzavrieť registrované partnerstvo. Denník N. May 13. Available online: https://dennikn.sk/1890701/ked-chcu-byt-spolu-maju-jedinu-moznost-uzavriet-registrovane-partnerstvo/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Gianfreda, Stella. 2018. Politicization of the Refugee Crisis?: A Content Analysis of Parliamentary Debates in Italy, the UK, and the EU. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 48: 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, Tom, and Mila Versteeg. 2021. The Bound Executive: Emergency Powers during the Pandemic. International Journal of Constitutional Law 19: 1498–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griglio, Elena. 2020. Parliamentary Oversight under the Covid-19 Emergency: Striving against Executive Dominance. The Theory and Practice of Legislation 8: 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, Joelle. 2020. States of Emergency. European Journal of Law Reform 22: 338–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasti, Petra. 2021. Democratic Erosion and Democratic Resilience in Central Europe during COVID-19. Mezinárodní Vztahy 56: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner-Burton, Emilie M., and Kiyoteru Tsutsui. 2005. Human Rights in a Globalizing World: The Paradox of Empty Promises. American Journal of Sociology 110: 1373–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajnal, György, Iga Jeziorska, and Éva Margit Kovács. 2021. Understanding Drivers of Illiberal Entrenchment at Critical Junctures: Institutional Responses to COVID-19 in Hungary and Poland. International Review of Administrative Sciences 87: 612–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henčeková, Slavomíra, and Šimon Drugda. 2020. Slovakia: Change of Government under COVID-19 Emergency. Verfassungsblog. May 22. Available online: https://verfassungsblog.de/slovakia-change-of-government-under-covid-19-emergency/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Huysmans, Jef, and Alessandra Buonfino. 2008. Politics of Exception and Unease: Immigration, Asylum and Terrorism in Parliamentary Debates in the UK. Political Studies 56: 766–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalyvas, Andreas. 2009. Democracy and the Politics of the Extraordinary: Max Weber, Carl Schmitt, and Hannah Arendt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Duncan. 2017. Carl Schmitt’s Political Theory of Dictatorship. In The Oxford Handbook of Carl Schmitt. Edited by Jens Meierhenrich and Oliver Simons. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 217–44. [Google Scholar]

- Klimovský, Daniel, and Juraj Nemec. 2021. The Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Responses from Various Policy Actors in the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 2020: An Introduction to a Special Issue. Scientific Papers of the University of Pardubice, Series D: Faculty of Economics and Administration 29: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováčová, Veronika. 2020. Slovenka v štátnej karanténe: Na hraniciach sme čakali hodiny v neľudských podmienkach. RegiónyZ. September 4. Available online: https://regiony.zoznam.sk/rozhovor-slovenka-v-statnej-karantene-na-hraniciach-sme-cakali-hodiny-v-neludskych-podmienkach/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Kovanič, Martin, and Michaela Šebíková. 2021. Populismus a nouzový stav: Analýza parlamentních rozprav v Poslanecké sněmovně Parlamentu České republiky. In Jazyk a politika. Na pomedzí lingvistiky a politológie VI. Edited by Radoslav Štefančík. Bratislava: EKONÓM. [Google Scholar]

- Krastev, Ivan. 2020. Is It Tomorrow Yet? Paradoxes of the Pandemic. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2020. Is There a Crisis of Democracy in Europe? Politische Vierteljahresschrift 61: 237–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lachmayer, Konrad. 2021a. Democracy, Death and Dying: The Potential and Limits of Legal Rationalisation. In Pandemocracy in Europe: Power, Parliaments and People in Times of COVID-19. Edited by Matthias C. Kettemann and Konrad Lachmayer. Oxford: Hart, pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lachmayer, Konrad. 2021b. Judging, Fast and Slow. Constitutional Adjudication in Times of COVID-19. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3935820. Rochester: Social Science Research Network. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Láštic, Erik. 2021. Slovakia: Political Developments and Data in 2020. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 60: 348–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, David S. 2017. Alternatives to Liberal Constitutional Democracy. Maryland Law Review 77: 223–43. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, Sanford, and Jack M. Balkin. 2009. Constitutional Dictatorship: Its Dangers and Its Design. Minnesota Law Review 94: 1789–866. [Google Scholar]

- Louwerse, Tom, Ulrich Sieberer, Or Tuttnauer, and Rudy B. Andeweg. 2021. Opposition in Times of Crisis: COVID-19 in Parliamentary Debates. West European Politics 44: 1025–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lührmann, Anna, and Bryan Rooney. 2021. Autocratization by Decree: States of Emergency and Democratic Decline. Comparative Politics 53: 617–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maďarová, Zuzana, Pavol Hardoš, and Alexandra Ostertágová. 2020. What Makes Life Grievable? Discursive Distribution of Vulnerability in the Pandemic. Mezinárodní Vztahy 55: 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meierhenrich, Jens. 2018. The Remnants of the Rechtsstaat: An Ethnography of Nazi Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menkel-Meadow, Carrie. 2019. Uses and Abuses of Socio-Legal Studies. In Routledge Handbook of Socio-Legal Theory and Methods. Edited by Naomi Creutzfeldt, Marc Mason and Kirsten McConnachie. London: Routledge, pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mészáros, Gábor. 2020. Rethinking the Theory of State of Exception After the Coronavirus Pandemic? The Case of Hungary. In Regional Law Review. Edited by Mario Reljanović. Belgrade: Institute of Comparative Law, pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2020a. Hlasovanie č. 13. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Default.aspx?sid=schodze/hlasovanie/hlasklub&ID=44226 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2020b. Parlamentná tlač 29. Dôvodová správa. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Dynamic/DocumentPreview.aspx?DocID=476589 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2020c. Parlamentná tlač 101. Návrh vlády na skrátené legislatívne konanie o vládnom návrhu zákona. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Dynamic/DocumentPreview.aspx?DocID=478663 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2020d. Vládny návrh ústavného zákona, ktorým sa mení a dopĺňa ústavný zákon č. 227/2002 Z. z. o bezpečnosti štátu v čase vojny, vojnového stavu, výnimočného stavu a núdzového stavu v znení neskorších predpisov. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Default.aspx?sid=zakony/cpt&ZakZborID=13&CisObdobia=8&ID=357 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- National Council of the Slovak Republic. 2020e. Vládny návrh zákona, ktorým sa mení a dopĺňa zákon č. 351/2011 Z. z. o elektronických komunikáciách v znení neskorších predpisov. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Default.aspx?sid=zakony/cpt&ZakZborID=13&CisObdobia=8&ID=175 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Neal, Andrew W. 2019. Security as Politics: Beyond the State of Exception. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nemec, Juraj, Ivan Maly, and Tatiana Chubarova. 2021. Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Potential Outcomes in Central and Eastern Europe: Comparing the Czech Republic, the Russian Federation, and the Slovak Republic. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 23: 282–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onursal, Recep, and Daniel Kirkpatrick. 2021. Is Extremism the ‘New’ Terrorism? The Convergence of ‘Extremism’ and ‘Terrorism’ in British Parliamentary Discourse. Terrorism and Political Violence 33: 1094–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSCE. 2020. The Functioning of Courts in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/5/5/469170.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Osvaldová, Lucia. 2020a. Pre zlé podmienky v štátnej karanténe sa niektorí boja vrátiť na Slovensko. Denník N. May 5. Available online: https://dennikn.sk/1881803/pre-zle-podmienky-v-statnej-karantene-sa-niektori-boja-vratit-na-slovensko/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Osvaldová, Lucia. 2020b. Slovensko otvorilo hranice, rúško je vonku dobrovoľné, štátna karanténa aj smart karanténa sa končia. Denník N. September 6. Available online: https://dennikn.sk/1923942/slovensko-otvorilo-hranice-rusko-je-vonku-dobrovolne-statna-karantena-aj-smartkarantena-koncia/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Plaváková, Lucia. 2020. K pochybeniam ohľadom štátnej karantény a zákazu vstupu cudzincov na územie SR (+ návrh riešení). Denník N. May 7. Available online: https://dennikn.sk/blog/1885440/k-pochybeniam-ohladom-statnej-karanteny-a-zakazu-vstupu-cudzincov-na-uzemie-sr-navrh-rieseni/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Pozen, David E., and Kim Lane Scheppele. 2020. Executive Underreach, in Pandemics and Otherwise. American Journal of International Law 114: 608–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- President of the Slovak Republic. 2020. Rozhodnutie o vrátení zákona. Available online: https://www.prezident.sk/upload-files/53854.doc (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Procházka, Radoslav. 2020. Týždeň v práve Rada Procházku: Svorky bez náhubku ocikávajú semafory. Denník N. May 11. Available online: https://dennikn.sk/2599126/tyzden-v-prave-rada-prochazku-svorky-bez-nahubku-ocikavaju-semafory/?ref=list (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Public Health Authority of the Slovak Republic. 2020. Zásady pre ubytovacie zariadenia hotelového typu poskytujúce ubytovanie osôb v karanténe v súvislosti s výskytom ochorenia COVID-19. Available online: https://www.uvzsr.sk/docs/info/covid19/Zasady_pre_ubytovacie_zariadenia_hoteloveho_typu_poskytujuce_ubytovanie_osob_v_karantene_v_suvislosti_s_vyskytom_ochorenia_COVID_19.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Rojo, Luisa Martín, and Teun A. van Dijk. 1997. ‘There Was a Problem, and It Was Solved!’: Legitimating the Expulsion of ‘Illegal’ Migrants in Spanish Parliamentary Discourse. Discourse & Society 8: 523–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, Clinton L. 1949. Constitutional Dictatorship in the Atomic Age. The Review of Politics 11: 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpli, Jaroslav. 2020. Odkaz plačkom, čo sa sťažujú na nelegálnu internáciu. Sme. August 5. Available online: https://komentare.sme.sk/c/22400584/odkaz-plackom-co-sa-stazuju-na-nelegalnu-internaciu.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Sajó, András, and Renáta Uitz. 2017. The Constitution of Freedom: An Introduction to Legal Constitutionalism. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Scheuerman, William E. 2019. The End of Law: Carl Schmitt in the Twenty-First Century, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Carl. 2006. Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. Edited by Tracy B. Strong. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Carl. 2013. Dictatorship. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schupmann, Benjamin. 2017. Carl Schmitt’s State and Constitutional Theory: A Critical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seedhouse, David. 2020. The Case for Democracy in the COVID-19 Pandemic. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- SITA. 2020. Prieskum: Väčšina Slovákov je spokojná s opatreniami vlády. Pravda.sk. May 5. Available online: https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/550571-prieskum-vacsina-slovakov-je-spokojna-s-tym-ako-vlada-zvlada-pandemiu/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Slovak National Centre for Human Rights. 2021. Správa o dodržiavaní ľudských práv vrátane zásady rovnakého zaobchádzania v Slovenskej republike za rok 2020; Bratislava: Slovenské národné stredisko pre ľudské práva. Available online: http://www.snslp.sk/wp-content/uploads/Sprava-o-LP-v-SR-za-rok-2020-.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Slovak Spectator. 2020a. PM Wants Slovakia to Be an Island of Hope for Europe, Carmakers Prolong Halt. April 1. Available online: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/22374229/pm-wants-slovakia-to-be-an-island-of-hope-for-europe-carmakers-prolong-halt-news-digest.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Slovak Spectator. 2020b. New Coronavirus Measures: Mandatory Isolation for Everybody Arriving in Slovakia. Spectator.Sme.Sk. April 5. Available online: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/22376960/new-coronavirus-measures-mandatory-isolation-for-everybody-arriving-in-slovakia.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Slovak Spectator. 2020c. Thousands of People Quarantined in Five Roma Communities. Spectator.Sme.Sk. April 9. Available online: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/22379925/thousands-of-people-quarantined-in-five-roma-communities.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Slovak Spectator. 2020d. Crossing the Border into Slovakia? Authorities Announced New Rules. Spectator.Sme.Sk. April 17. Available online: https://spectator.sme.sk/c/22385972/crossing-the-border-into-slovakia-government-has-passed-new-rules.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Šteňo, Andrej. 2020. Facemasks against COVID-19: Why Slovakia Became the Trailblazer. Euractiv.com. April 28. Available online: https://www.euractiv.com/section/coronavirus/opinion/facemasks-against-covid-19-why-slovakia-became-the-trailblazer/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Steuer, Max. 2020. Slovak Constitutionalism and the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Implications of State Panic. IACL-IADC Blog. September 4. Available online: https://blog-iacl-aidc.org/2020-posts/2020/4/9/slovak-constitutionalism-and-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-implications-of-state-panic (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Steuer, Max. 2021. Slovakia’s Democracy and the COVID-19 Pandemic: When Executive Communication Fails. Verfassungsblog. February 26. Available online: https://verfassungsblog.de/slovakias-democracy-and-the-covid-19-pandemic-when-executive-communication-fails/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- TASR. 2021. Ústavný súd dostal 80 podaní k opatreniam pre pandémiu COVID-19. April 29. Available online: https://www.teraz.sk/slovensko/ustavny-sud-dostal-80-podani-k-opatr/545512-clanok.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Urbanovics, Anna, Péter Sasvári, and Bálint Teleki. 2021. Evaluation of the COVID-19 Regulations in the Visegrad Group. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy 15: 645–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V-Dem Institute. 2021. Slovakia (Pandemic Backsliding Index). Available online: https://github.com/vdeminstitute/pandem/blob/master/by_country/Slovakia.md (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Vinx, Lars, and Samuel Garrett Zeitlin, eds. 2021. Carl Schmitt’s Early Legal-Theoretical Writings: Statute and Judgment and the Value of the State and the Significance of the Individual. Lars Vinx, and Samuel Garrett Zeitlin, transs. Cambridge Studies in Constitutional Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnerová, Eliška. 2009. Základní práva. In Komunistické právo v Československu. Edited by Michal Bobek, Pavel Molek and Vojtěch Šimíček. Brno: MPÚ, pp. 330–63. Available online: http://www.komunistickepravo.cz/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Walker, Shaun, and Helena Smith. 2020. Why Has Eastern Europe Suffered Less from Coronavirus than the West? The Guardian. May 5. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/05/why-has-eastern-europe-suffered-less-from-coronavirus-than-the-west (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Webber, Grégoire, Paul Yowell, Richard Ekins, Maris Köpcke, Bradley W. Miller, and Francisco J. Urbina. 2018. Legislated Rights: Securing Human Rights through Legislation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, Joseph. 2021. Cancelling Carl Schmitt? EJIL: Talk! August 13. Available online: https://www.ejiltalk.org/cancelling-carl-schmitt/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Previous studies considered the invocation of actual or perceived emergencies by speeches and debates in the legislatures, particularly in the context of restricting migrant and refugee rights and securitizing migration processes (Huysmans and Buonfino 2008; Rojo and van Dijk 1997). For a recent article covering a selection of Western European countries, see Louwerse et al. (2021). However, the authors’ focus there is on the sentiments of the parliamentary opposition in general in terms of support for the COVID-19-induced measures, rather than the substantive frames that have been invoked. |

| 2 | Theories of the exception are not to be equated with theories of constituent power, focusing on the establishment of new political communities. The two are nevertheless related via the extra-constitutional understandings of both. As indicated by Kalyvas (2009, p. 297), ‘[t]he extraordinary is a reminder that instituted reality does not exhaust and cannot consume all forms of political action, which often emerge at the edges of the existing statist nomos.’ Not all actions (especially actions of violence) are political in this sense. |

| 3 | For example, the Slovak Constitution, in Art. 1 sec. 1, stipulates that ‘[t]he Slovak Republic is a sovereign, democratic state governed by the rule of law. It is not bound to any ideology or religion.’ |

| 4 | An overview of Agamben’s argument is available in Douglas (2009, p. 35). |

| 5 | Agamben’s theories are more complicated and presented here only in a concise format. Agamben uses the concept of the ‘camp’ to denote an environment of complete evaporation of law (Agamben 2003, p. 37). The use of the term ‘quarantine camps’ by a Slovak democratic politician creates a disturbing conceptual analogy. See Denník N (2020). |

| 6 | In other words, there is an overlap between facticity and legal norms, which results in more difficulties in explaining what law (equated with executive power) actually is (Agamben 2005, p. 29). |

| 7 | For instance, due to the absence of hospital beds or reliable vaccination. See Lachmayer (2021a, p. 52). |

| 8 | Dawson and Hanley (2016, p. 22) write on the ‘weakly embedded institutions in East-Central European democracies.’ Kriesi (2020, pp. 239, 257) opposes conclusions according to which Western democracy is in irreversible crisis, but acknowledges the absent stable institutional basis for democracy in Central and Eastern Europe. |

| 9 | On the illiberal measures adopted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, see Hajnal et al. (2021). |

| 10 | For example, the constitutional position of the Communist Party or the subordination of judicial decision making to ideological goals cast a long shadow over the post-communist transformation of the Slovak political system. See Wagnerová (2009, p. 352 et seq.). |

| 11 | Constitutional Act on State Security at the Time of War, State of War, State of Exception, and State of Emergency. |

| 12 | For the situation of a pandemic, the ‘state of emergency’ is the respective type of emergency that may be invoked (the other three states of emergency being war, state of war and state of exception). |

| 13 | On the violations of human rights of the Roma population see ECRI (2020, pp. 29–30, 33). These major violations have been noted also by the Pandemic Backsliding Index (V-Dem Institute 2021), though only after the first monitoring quarter. |

| 14 | From 21 March 2020 a new cabinet of Igor Matovič stepped in, replacing the cabinet of Peter Pellegrini after the elections on 29 February 2020. From 1 April 2021, after the reconstruction of the cabinet due to the resignation of PM Matovič in response to the lack of capability to address the rise of cases during the pandemic, a new cabinet of PM Eduard Heger was sworn in, with Matovič continuing as the minister of finance. |

| 15 | For the role of parliaments in human rights protection, see Webber et al. (2018); for the role of courts, see, for example, Baer (2020). |

| 16 | There were three dissenting opinions in the 13-member Court. However, Slovak Constitutional Court judges may vote against the motion and not attach a dissenting opinion, so it is impossible to say with certainty that all ten other judges agreed with the motion. |

| 17 | For the importance of parliaments deciding on security issues, see Neal (2019, p. 286ff.). |

| 18 | A recent analysis (in Czech) covered the contributions by one of the Czech political parties (ANO) in the lower chamber (Chamber of Deputies) of the Czech parliament, arguing that, contrary to the public presentation of the party as a populist one, it did not employ populist rhetoric, because, as a coalition party, it was seen as responsible for the management of the pandemic (Kovanič and Šebíková 2021). In focusing on how a single party managed to assert its positions and preferences, that contribution stands closer to a partisan–rhetorical than a deliberative approach. Lucia Berdisová (2020b) highlighted the insensitivity of the parliamentarians via illustrating the verbal disrespect towards the 2019 annual report submitted to the National Council by the Slovak ombudswoman. |

| 19 | For the results of the Slovak parliamentary elections in 2020, see Láštic (2021, p. 351). |

| 20 | The speeches of parliamentary rapporteurs were not counted. |

| 21 | As this was a deliberation on a piece of legislation previously vetoed by the president, no minister introduced it. |

| 22 | Hlas was created via a split from Smer-SD, the sole (2012–2016) and main coalition (2016–2020) governing party in Slovakia. |

| 23 | In Slovakia, MPs can only be elected from a party list. However, these MPs have severed the relationship with the political party on the list of which they were elected, after assuming office. Both coalition and opposition parties lost a few MPs who distanced themselves from the parties or joined another party. The party affiliation of the speaker was determined as valid at the time of the debate, hence the same speaker could become independent in a later debate, despite having spoken as an affiliate of one of the parliamentary parties during an earlier debate. |

| 24 | The Court also presented itself as the protector of the individual from the ‘collection and abuse of personal data […] with the aim to ensure a truly free development of the individual’s personality’ (PL. ÚS 13/2020, § 69). |

| 25 | The rights that may be restricted are the inviolability of property and privacy, the prohibition of forced labour, the freedom of movement and residence, the freedom of assembly and the freedom of media (mandatory government access to broadcast services to disseminate relevant information to the citizens) (Act No. 414/2020 Coll., Art. 8.). |

| 26 | Paraphrasing another exchange in the July 2020 debate, one could say that the overwhelming belief in the process was that there are ‘evil people’ who want to evade the regulations, and so the rights of all belonging to a certain category (e.g., returning from abroad) need to be restricted in order to tackle the malice of these few evaders of the regulations. |

| 27 | For instance, MP Muňko advocated the introduction of ‘monitoring bracelets’ instead of location tracing via mobile phones. |

| 28 | Here, the MP engages in convenient ‘doublespeak’, when he does not specify that the reference to ‘quarantine’ in his statement only encompasses the quarantine in state facilities, rather than home quarantine. Thus, the statement also appeals to COVID-19 denialists who reject all kinds of quarantine measures. |

| 29 | Agamben’s framework might be used to critically scrutinize the concepts of ‘executive underreach’ and ‘executive overreach’ representing a deliberative failure or overreaction of the executive when solving a problem that it is able to address. See Pozen and Scheppele (2020). The Slovak executive response appears to be neither a case of underreach, nor of overreach. Instead, it aligns with resignation to provide justifications and communicate the necessity of the measures. |

| 30 | For example, Igor Matovič: ‘From the position of restrictions, we are proceeding towards the responsibility of the peoples’ (Osvaldová 2020b). |

| Date of the Debate | Minister Introducing the Agenda Point | Number of MP Speeches | Number of MP Short Interventions (faktické poznámky) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24–25 March 2020 | Kolíková (minister of justice) | 10 | 79 |

| 14–15 May 2020 | Krajčí (minister of health) | 2 | 13 |

| 14–15 July 2020 | Doležal (minister of transport and construction) | 5 | 18 |

| 2 September 2020 | –21 | 2 | 1 |

| 8–9 December 2020 | Holý (vice chairperson of the cabinet for legislation and strategic planning) | 11 | 60 |

| Total: 201 contributions | 30 | 171 | |

| Date of the Debate | Political Party of the Speakers (Number of Speeches) | Number of MP Short Interventions (faktické poznámky) | Hlas22 | Total (of Which Speeches) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OĽaNO | Smer-SD | Sme Rodina | Kotlebovci | SaS | Za ľudí | Independent23 | ||||

| 24–25 March 2020 | Smer-SD (4), Kotlebovci (3), SaS (3) | 13 | 28 | - | 20 | 17 | 1 | - | / | 89 (10) |

| 14–15 May 2020 | Smer-SD (1), Independent (1) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | - | / | 15 (2) |

| 14–15 July 2020 | OĽaNO (1), Smer-SD (3), SaS (1) | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | - | 2 | - | 23 (5) |

| 2 September 2020 | Smer-SD (1), Kotlebovci (1) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (2) |

| 8–9 December 2020 | Smer-SD (1), Kotlebovci (3), Hlas (1), Sme Rodina (1), Independent (2), OľaNO (2), SaS (1) | 5 | 14 | 1 | 23 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 71 (11) |

| Total | Smer-SD (10), Kotlebovci (7), Hlas (1), Sme Rodina (1), Independent (3), OľaNO (3), SaS (5) | 26 | 44 | 9 | 46 | 30 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 201 (30) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steuer, M. The Extreme Right as a Defender of Human Rights? Parliamentary Debates on COVID-19 Emergency Legislation in Slovakia. Laws 2022, 11, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11020017

Steuer M. The Extreme Right as a Defender of Human Rights? Parliamentary Debates on COVID-19 Emergency Legislation in Slovakia. Laws. 2022; 11(2):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11020017

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteuer, Max. 2022. "The Extreme Right as a Defender of Human Rights? Parliamentary Debates on COVID-19 Emergency Legislation in Slovakia" Laws 11, no. 2: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11020017

APA StyleSteuer, M. (2022). The Extreme Right as a Defender of Human Rights? Parliamentary Debates on COVID-19 Emergency Legislation in Slovakia. Laws, 11(2), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11020017