1. Introduction

Existing policies to “get tough” on crime have not only failed to control crime but have contributed to an enormous increase in the number of incarcerated individuals [

1,

2]. This suggests that the underlying premise—stiffer sentences deter criminals—may be incorrect. Furthermore, even in the unlikely event that incarceration rates could be tripled through a tripling of law enforcement and prison budgets, the available data suggest that the probability that an offender would be apprehended and incarcerated would remain low. As of 2004, the probability that an offender would be incarcerated was negligible for residential burglary (0.8 percent), vehicle theft (0.6 percent), robbery (1.7 percent), and assault (1.2 percent); and fairly small for rape (12.4 percent) [

3]. This suggests that the deterrent effect of policies to “get tough” on crime would remain weak, and suggests a need to switch paradigms.

An alternative paradigm relies on the use of global positioning system (GPS) electronic monitoring (EM) bracelets that are continuously attached to parolees and probationers in order to identify their locations and deter criminal behavior (because offenders know that the bracelets would place them at the scene of any crimes they commit, essentially ensuring a conviction) [

4].

The alternative paradigm focuses on repeat offenders who generate a disproportionate amount of crime. Habitual offenders are a major source of crime and, thus, an effective deterrent could have enormous social benefits, especially if it is applied early and saves what would otherwise be habitual offenders from a life of crime. Based on self-reported crimes over their existing criminal careers, a cohort of 500 habitual offenders were arrested an average of 60 times each and created victim and criminal justice costs, and lost offender earnings, exceeding a total of $570 million [

5]. EM plus home detention may be viewed as an appropriate intervention for high-risk youth whose first encounters with the criminal justice system typically result in a sentence of probation. This form of early intervention could have disproportionate benefits. For example, Welsh, Loeber and Stevens

et al. found that a typical cohort of 500 boys in an urban area, beginning in childhood through late adolescence, created victimization costs that were conservatively estimated to range from $89 million to $110 million [

6]. Miller, Fisher and Cohen found that in Pennsylvania alone, the state’s juvenile offenders created a total of $2.6 billion in victim costs during a single year [

7]. On an individual basis, Cohen estimated that the cost incurred by society for each chronic juvenile offender ranged from $1.7 million to $2.3 million [

8]. However, new evidence, using estimates of the public’s willingness to pay for reductions in crime, suggests that the costs incurred by society for each chronic juvenile offender are much greater, ranging from $2.6 million to $5.3 million [

9]. EM plus home detention could potentially be very effective, and very cost-effective, in aborting the criminal careers of individuals who would otherwise settle into a pattern of habitual offending.

The alternative paradigm conceptualizes the problem of criminal behavior as a treatable condition requiring a monitoring bracelet and a home detention curfew for an extended period of time, but otherwise allows offenders to seek employment, education, training, and counseling in the community, and to live in their own homes with their families. The alternative paradigm is based upon the view that offenders have poor impulse control and may be easily tempted by the short-term gain of crime [

10]. Offenders may fail to consider future consequences or may believe that the probability of arrest and incarceration is slim [

10]. In either case, an EM bracelet may help offenders to control their impulses and make better decisions [

11].

In this view, it is unnecessary to apply moral judgments about the character of individuals who are convicted of crimes, or the failure of society to get tough on crime, or the failure of society to address poverty and unemployment. In this view, an EM bracelet is a device that assists offenders to avoid the temptation of crime. By analogy, a pacemaker is a device that assists individuals whose heart muscles do not function properly and eyeglasses are devices that assist individuals whose eyes do not focus properly. It is unnecessary to apply moral judgments to individuals who require pacemakers or eyeglasses. In the same way, it is unnecessary to apply moral judgments to individuals who lack impulse control and require EM.

This view suggests that the nature and causes of criminal behavior have been misunderstood. Failure to properly diagnose the problem has resulted in the application of misguided solutions. The result has been a continuation of crime, a failure to protect society, and demonization of individuals who commit crimes.

This article proposes a change in public policy that promises to greatly reduce major crime in the United States, protect society, eliminate prison overcrowding, and save taxpayer dollars. This policy would employ EM technology in a way that discourages individuals who might otherwise be tempted to commit crimes. The approach is arguably more effective, efficient, humane and ethical than any alternative strategy and potentially could revolutionize law enforcement and the American criminal justice system.

Section 2 of this article describes EM and briefly reviews qualitative studies involving offenders in the United Kingdom, Belgium, and the United States suggesting why offenders who are electronically monitored respond positively, cooperate and do not attempt to abscond, and why the technology helps them to resist the temptation to commit new crimes.

Section 3 briefly reviews findings from the most rigorous studies regarding the impact of EM during and after the period of monitoring.

Section 4 describes the proposed policy and changes in state laws that may be required to implement the proposed policy.

Section 5 describes the estimated benefits and costs of the proposed policy.

Section 6 analyzes the failures of current policy.

Section 7 analyzes prospects for changing state laws in the ways required by the proposed policy.

Section 8 describes U.S. Senate Bill 1410. This bill would implement reductions in prison sentences, as envisioned in the proposed policy. The bill received broad support from a spectrum of stakeholders, suggesting that the proposed policy might also receive broad support.

Section 9 explains the significance of the material reviewed in

Section 7 and

Section 8.

Section 10 analyzes the interests and concerns of various stakeholders with regard to criminal justice reform.

Section 11 suggests how it may be possible to secure the cooperation of state legislators to sponsor and support the passage of legislation that would implement the proposed policy.

Section 12 concludes.

The article explains why Republican as well as Democratic voters and leaders may be expected to support the proposed policy and why the level of support may be sufficient to implement the proposed policy. The article draws upon the results of a national opinion survey, focusing on an examination of responses from Republican and Democratic voters to hypothetical policy options that are closely-aligned with the proposed policy, and draws upon an analysis demonstrating broad national support for sentencing reforms and reductions in sentences that are closely-aligned with the proposed policy.

2. Electronic Monitoring

Global positioning technology now allows law enforcement officials to electronically monitor parolees and probationers through ankle bracelets that track the second-by-second location of each individual. As a consequence, parolees and probationers who are required to wear these bracelets may be deterred from committing new crimes because they know that these devices would place them at the scene of any crimes they commit, essentially ensuring a conviction. Offenders are deterred from cutting off the bracelet because the bracelet is designed to transmit an alarm to law enforcement authorities who would then arrest and imprison the offenders. Bracelets that detect alcohol consumption are available and could be used to deter alcohol-related repeat offenders. The bracelets are waterproof and designed to be worn 24 h per day. A study by Britain’s National Audit Office (NAO), which is responsible for auditing the performance of Britain’s national EM and home detention program serving over 225,000 offenders, concluded that “the technology is robust: the equipment and monitoring system work” ([

12], p. 16).

In some states, offenders may be sentenced to prison followed by a period of home detention and electronic monitoring where offenders are typically required to stay within a specified home location during specified curfew hours but are otherwise permitted (or required) to leave the home to seek employment, attend counseling sessions or educational or vocational training programs, and attend to any other court-approved activities. In California, for example, a court may split a sentence between time served in jail and time served in the form of supervised release [

2]. In other states, changes in state law may be needed if judges are to be permitted to impose this type of split sentence.

Interviews commissioned by Britain’s NAO suggest that offenders view the experience positively and believe that it facilitates their adjustment to work and family routines. Interviewees were “generally positive” about their experiences ([

12], p. 44). Younger males in particular were “quite happy” with home detention and viewed it as a good method of easing them back into society ([

12], p. 44). Interviewees asserted that, without EM and home detention, it would be easy to slip back into criminal routines ([

12], p. 44). Interviewees also asserted that EM was more effective at halting the development of a criminal career, compared to serving out their sentences in prison, which provided an education in criminal activity ([

12], p. 44). Interviewees generally felt that release to home detention had a positive effect on social relationships with family ([

12], p. 45). In general, interviewees felt that the monitoring device was satisfactory to wear ([

12], p. 46). They stated that they had not attempted to tamper with the equipment as the risks of being discovered were too high ([

12], p. 46).

Interviews with Belgian offenders who were electronically monitored found similar results. Overall, most preferred EM to prison [

13]. “Not being in prison” was seen as one of the most attractive elements of EM ([

13], p. 277). Statements such as “it is ten times better than being in jail” were frequently made in favor of EM ([

13], p. 277). Most respondents experienced EM as not being overly punitive, when compared with their experience of prison [

13].

Interviews with American offenders who were electronically monitored found similar results. A survey of American offenders who were monitored found that a majority felt that the electronic monitoring experience was positive, at least in comparison to jail [

14]. Most offenders were happy to be on house arrest rather than in jail [

14]. One respondent, for instance, reported that “EM helped keep my life together” ([

14], p. 88). Another offender discussed how the program changed both his behavior and attitudes toward the law: electronic monitoring “affected my life profoundly, in a good way” ([

14], p. 88). Offenders believed that monitoring was effective: “wherever you go, they are ahead of you” ([

15], p. 425). Offenders believed that efforts to tamper with a bracelet would be readily detected: “they’d know if the bracelet were off” ([

15], p. 425). EM helped offenders to control their impulses to commit crime: EM “made me think twice about doing it again” ([

15], p. 429). EM, in the words of one offender, was “more likely to rehabilitate than jail” ([

15], p. 430).

3. Impact of EM

In perhaps the best controlled, large-scale evaluation of the impact of EM on crime

during the period of monitoring, involving 75,661 Florida offenders placed on home detention from 1998 to 2002, Padgett, Bales and Blomberg controlled for 62 independent factors influencing community supervision success or failure, applied proportional-hazards survival analysis, and found that EM is extremely effective at preventing offenders from committing new offenses while they are monitored [

11]. No previous study of EM controlled for this array of variables nor involved such a large sample. All previous studies had serious limitations and were of low quality. Overall, offenders monitored with GPS devices were 94.7 percent less likely to commit a new offense than offenders who were not monitored [

11]. Significantly, Padgett

et al. concluded that “EM works equally well for all ‘types’ of serious offenders” ([

11], p. 83). Padgett

et al. found that GPS-monitored violent offenders were 91.2 percent less likely to abscond than their non-monitored counterparts, suggesting an extremely high rate of compliance by monitored offenders [

11]. Significantly, Padgett

et al. found “no clear evidence that, overall, the decision to monitor offenders on home confinement with enhanced electronic control mechanisms results in ‘front-end’ net-widening. In other words, offenders sentenced to home confinement with EM seem to have posed a significantly higher risk to public safety and would have had a higher likelihood of receiving a prison sentence if not for the availability of EM as an enhanced control mechanism.” ([

11], p. 77). Furthermore, “offenders on GPS monitoring are 90.2% less likely than offenders on home confinement without EM to be revoked for a technical violation” ([

11], p. 79). The back-end “net” was largely eliminated.

In perhaps the best controlled evaluation of the impact of EM on recidivism

after monitoring is discontinued, Marklund and Holmberg studied 260 Swedish offenders who were sentenced to a minimum of two years imprisonment (and therefore convicted of relatively serious crimes) but were electronically-monitored and served the final portion of their sentences in home detention [

16]. Monitored individuals were matched with similar prison inmates based on the number of prior convictions and the predicted re-offending risk from a logistic regression model. Marklund and Holmberg found that offenders in the EM group relapsed at a lower rate: 26 percent, compared to 38 percent of the control group, during the three year period after monitoring ends [

16]. The EM group relapsed into serious crime at a lower rate: 14 percent, compared to 26 percent of the control group, during the three year period after monitoring ends [

16]. This suggests that EM has a significant effect in reducing criminality during the three year period after monitoring ends, in addition to the substantial effect found by Padgett

et al. during the period of monitoring [

11].

4. Proposed Policy

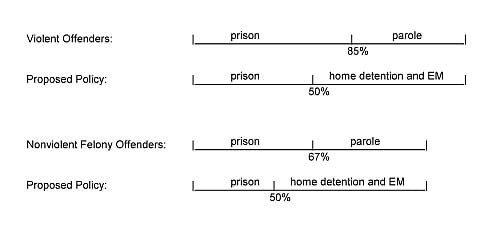

In most states, violent felony offenders typically serve 85 percent of their sentences, and nonviolent felony offenders typically serve 67 percent of their sentences, before parole. In comparison, the proposed policy for reducing crime involves sentencing all felony offenders to serve 50 percent of their sentences in prison, followed by a period of home detention and EM equal to 50 percent of their sentences, with home detention and EM extended for an additional period equal to conventional periods of parole (

Figure 1). Offenders who would normally be sentenced to probation would instead be sentenced to an equivalent period of home detention and EM.

This change in state laws may be justified based on the results of the Padgett

et al. study suggesting that the number of crimes committed by parolees and probationers could be drastically reduced if offenders were electronically monitored and subject to home detention [

11]. To accomplish this, state laws could be changed to permit judges to impose EM and home detention during the second half of each sentence—historically, the time period where many offenders have been released into the community on parole and, historically, the period when many offenders relapse and commit new crimes. This change in state laws could be justified on the basis that it would reduce the many violent crimes that would otherwise occur while offenders are on parole. The second half of each sentence would essentially be an intensive form of supervised parole involving electronic monitoring and home detention, after a term in a state prison or county jail. While a split sentence returns offenders to the community more quickly, compared to conventional policies, the period of home detention and electronic monitoring would be extended to cover the conventional period of parole. Offenders would be released into the community relatively early but would be heavily supervised through a lengthy period of home detention and electronic monitoring in order to protect society as well as protect risky offenders from the temptation to commit new crimes. To ensure that current and future state inmates would receive equal treatment, the changes in state laws could include provisions that would give current state inmates the option of release to home detention and electronic monitoring throughout their period of parole, upon completion of 50 percent of their sentences and subject to the approval of a parole board.

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison of conventional policies and sentencing under the proposed policy [

17].

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison of conventional policies and sentencing under the proposed policy [

17].

5. Benefits and Costs

The estimated benefits and costs of the proposed policy have been calculated based on Padgett

et al.’s results suggesting that EM plus home detention would avert 94.7 percent of the crimes typically committed by parolees and probationers [

11,

17].

Table 1 breaks down the estimated reduction in crime and the total value of the averted crime attributable to the proposed policy.

An estimated total of 781,383 crimes would be averted annually. Significantly, 466,748 violent crimes would be averted annually, including 68,792 murders, 13,378 deaths by manslaughter, 14,205 kidnappings, 29,824 rapes, 43,211 other sexual assaults, 191,700 robberies, and 105,639 assaults. In addition, an estimated 190,582 burglaries, 79,637 thefts, 36,366 motor vehicle thefts, and 8050 acts of arson would be averted annually.

The social value of the annual reduction in crime, $481.1 billion, was calculated based on estimates of the averted loss to each victim and averted property losses for each crime [

18,

19], plus averted costs of incarceration [

20] based on average time served per offender for each of eleven major categories of crime [

21], plus averted costs of incarceration when offenders are released early (not included in

Table 1), adjusted for inflation, with incarceration savings discounted at an annual rate of 3.5 percent (since these savings would accrue over time).

Table 1.

Averted crime with home detention and electronic monitoring, by offense [

17].

Table 1.

Averted crime with home detention and electronic monitoring, by offense [17].

| Category of most serious offense | Annual reduction in crime with EM | Averted victim and property loss per crime | Averted incarceration costs per crime | Total value of averted crime per year |

|---|

| Violent offense | 466,748 | | | |

| Murder | 68,792 | 4,467,460 | 307,678 | 328,488,989,958 |

| Negligent manslaughter | 13,378 | 4,467,460 | 112,020 | 61,262,259,004 |

| Kidnapping | 14,205 | 226,893 | 112,020 | 4,814,193,879 |

| Rape | 29,824 | 132,200 | 195,932 | 9,786,214,128 |

| Other sexual assault | 43,211 | 132,200 | 112,020 | 10,553,008,254 |

| Robbery | 191,700 | 12,156 | 140,000 | 29,168,446,707 |

| Assault | 105,639 | 14,284 | 84,030 | 10,385,723,056 |

| Property offense | 314,635 | | | |

| Burglary | 190,582 | 2127 | 56,030 | 11,083,631,931 |

| Larceny/theft | 79,637 | 562 | 56,030 | 4,506,818,315 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 36,366 | 5622 | 28,020 | 1,223,439,257 |

| Arson | 8050 | 56,983 | 84,030 | 1,135,122,063 |

| Total (all offenses) | 781,383 | | | 472,407,846,552 |

If prison terms are reduced from 85 to 50 percent of sentences for violent offenders, the proposed policy would reduce the corresponding prison population by 41.18 percent. Similarly, if prison terms are reduced from 67 to 50 percent of sentences for nonviolent offenders, the proposed policy would reduce the corresponding prison population by 25.37 percent. These changes would virtually eliminate prison overcrowding and the need to build new prisons. Currently, overcrowding is a serious issue: 13 states exceeded their maximum prison capacities in 2008 [

22]. In California, a federal court ordered the state to reduce its prison population by one-third in order to comply with constitutional requirements [

23]. Reducing the length of state prison terms would not only reduce overcrowding but would also save taxpayers an estimated $8.7 billion annually [

17].

The total cost of monitoring each offender, including personnel costs associated with parole agents, is $20.37 per day [

17]. The annual cost of monitoring all 5,095,200 parolees and probationers in 2008 equals $37,883,066,760 [

17]. The benefit-cost ratio (benefits divided by costs) equals 12.70, implying that society would gain $12.70 for every dollar expended on the proposed form of EM plus home detention for all parolees and probationers [

17]. If monitoring of probationers is limited to those with felony convictions (and if probationers who are typically returned to state prison are those convicted of felonies), the benefit-cost ratio equals 25.81, implying that society would gain $25.81 for every dollar expended on EM plus home detention for all parolees and felony probationers [

17].

6. A Failure of Policy

The existence of a highly-efficient but underutilized approach for reducing crime suggests a failure of existing policy. Current policies have failed to adequately protect society and have also failed to protect offenders from an inability to control their impulses. This represents a double failure. In addition, existing policies result in high rates of false convictions. There have been 317 cases of post-conviction DNA exonerations in the United States [

24]. The total number of years served by these individuals is approximately 4249 [

24]. DNA exoneration cases provide irrefutable proof that wrongful convictions are not isolated or rare events. Furthermore, since DNA testing is rarely applied to investigate wrongful convictions for lower-level crimes, the true number of wrongful convictions is likely to be a large multiple of the known cases of wrongful conviction. This represents a third failure. In addition, after conviction, inmates enter a prison system and are subjected to practices that Amnesty International has characterized as “inhuman” ([

25], p. 4). This represents a fourth failure.

These failures are illustrated by the tangled case of Sabrina Buie, an 11-year-old girl. In 1983, Buie was brutally raped and murdered in Red Springs, North Carolina by Roscoe Artis, who had a history of convictions for sexual assault stretching back to 1957, was being sought by police and, under the proposed policy, would most likely have been subject to EM and home detention at the time he raped and murdered Buie and would potentially have been deterred from committing this crime if EM and home detention had been ordered by a judge during the period of parole following his previous convictions. Instead, he not only victimized Buie, but also murdered 16-year-old Joann Brockman on 22 October 1983, less than a month after he killed Buie. The tragedy was compounded through the false convictions of Henry Lee McCollum, now age 50, who spent three decades on death row, and Leon Brown, age 46, who served 31 years of a life sentence for Buie’s rape and murder. Vilified as depraved murderers and deprived of the best years of their lives, both men were recently declared innocent and released based upon DNA evidence that cleared them and implicated Artis [

26]. McCollum was 19 years old at the time he was incarcerated; Brown was 15 years old.

The Roscoe Artis case illustrates the failure of current policies to do much about habitual offenders. Habitual offenders continue to commit crimes. Current law enforcement practices are weak and ineffectual in stopping repeat crime. The Artis case also illustrates the phenomena of false convictions and the destruction of lives that occurs when innocent individuals are incarcerated for lengthy periods of time under conditions that Amnesty International characterizes as “inhuman”. If the implementation of EM technology could prevent 94.7 percent of repeat crime, the failure to implement this technology is an egregious failure of current policy.

Policymakers have an obligation to ensure that justice is served, society is protected to the maximum extent feasible, and an effective approach is implemented to reduce habitual offending. This goal could be accomplished, at least in part, through the proposed policy. Crime would be reduced, habitual offenders would be deterred, and fewer false convictions would occur (because there would be less crime and, therefore, fewer opportunities for false convictions to occur).

If existing policy has failed, what is the cause of this failure? First, it appears that the public and policymakers have misunderstood the nature and cause of crime, and have persisted in applying misguided solutions. If habitual criminals can be deterred through the use of EM devices, then the continuation of crime may be understood as a failure of society to apply EM devices. It appears that the application of EM devices—in 94.7 percent of all cases—trumps other causes of crime. Whether those other causes involve psychological dysfunction, emotional dysfunction, or socioeconomic dysfunction (such as inadequate education or inadequate employment opportunities), the application of EM appears to override the influence of those other causes. If so, society arguably has an obligation to apply EM in order to protect society as well as to protect habitual criminals from the temptation to commit new crimes. In the same way, society has an obligation to supply pacemakers to individuals whose heart muscles do not function properly, and an obligation to supply eyeglasses to individuals whose eyes do not focus properly. If society has an opportunity to apply EM but does not do so, and if the consequence is that habitual criminals continue to commit new crimes, then the cause of continued crime is arguably society’s failure to take the necessary action.

A second reason for the failure of existing policy is a failure to appreciate and apply what has been learned from the Padgett

et al. study regarding the impact of EM. Various authors have urged caution in interpreting the results of this study [

27,

28]. One concern focuses on an alleged lack of clarity about the aspects of the monitored offenders’ supervision that actually changed their behavior. However, Padgett

et al. employed statistical analyses to control for 62 independent factors influencing outcomes. By controlling for these factors, the analysis isolated the effect of EM plus home detention from other factors influencing outcomes. The analysis found that EM plus home detention reduced recidivism by 94.7 percent, including recidivism with regard to major offenses, while controlling for 62 factors that would otherwise bias the results. No other study controlled for this many factors.

Future studies of equivalent methodological rigor may yet contradict Padgett

et al.’s results and may provide a basis for challenging those results. However, until a rigorous study is conducted that contradicts Padgett

et al.’s results, the appropriate conclusion is that the best available empirical evaluation of the impact of EM indicates that EM deters 94.7 percent of all repeat crime and, furthermore, “EM works equally well for all ‘types’ of serious offenders” ([

11], p. 83). Examples of crimes committed by offenders while being electronically monitored do not contradict Padgett

et al.’s results because those results indicate that 5.3 percent of repeat crime is not deterred by EM.

The results indicate that EM deters 94.7 percent of all crime when applied under conditions similar to the conditions in Florida when the Padgett et al. study was conducted. While it can be assumed that poor implementation may lead to poor results, the results of the Padgett et al. study indicate that a level of implementation similar to the level achieved in the Padgett et al. study would produce results similar to the results in the Padgett et al. study. It is likely that measures are needed to ensure adequate implementation, but the results of the Padgett et al. study indicate that this level of implementation is feasible and practical on a large scale.

A third reason for the failure of existing policy is a failure to formulate attractive proposals for reform of the criminal justice system. An attractive proposal would clearly explain how the proposed changes would efficiently reduce crime and protect society without expending enormous resources on new prisons, expansion of the corrections system and law enforcement. An attractive proposal would build on research such as the Padgett et al. study to formulate recommendations about a strategy for reducing crime that can be supported by both liberal and conservative voters and political leaders.

A fourth reason for the failure of existing policy is a failure of organization. Policy change in the U.S. is driven by coalitions of organized lobbyists. However, with some notable exceptions, advocates of criminal justice reform have not organized an effective coalition for change and have not applied basic principles for achieving change. To achieve change, advocates of reform will have to build coalitions focused around concrete, attractive proposals for change that may be translated into legislative bills with strong sponsors or ballot initiatives with strong support.

A fifth reason for the failure of existing policy is a failure of communication. To achieve change, advocates of reform will need to construct a persuasive, easily-understood message that focuses on evidence-based crime reduction policies, appeals to American values of fairness, justice and efficiency and promises real change. This message might focus on descriptive terms such as “evidence-based crime reduction policies”, “electronically-monitored parole and probation”, “offender-focused electronic monitoring”, “evidence-based deterrence policies”, “GPS ankle-bracelets”, “impulse control”, “impulse suppression”, “impulse management”, “impulse arrest”, “impulse deterrence”, “repeat offenders”, “habitual offenders”, “protection of society”, and “split-sentencing”.

7. Prospects

What are the prospects for changing state laws in the ways required by the proposed policy? State laws may be changed through legislative bills introduced by members of state assemblies, or they may be changed through ballot initiatives introduced by citizens. In either case, prospects for change depend on the balance between constituents who would support the proposed policy and constituents who would oppose it. If more constituents support the proposed policy than are opposed to it, their legislators are likely to support it. If more voters support the proposed policy than are opposed to it, a ballot initiative is likely to pass.

An indication of the relative strength of potential supporters

versus potential opponents may be inferred from the approval by California voters of Proposition 47 on 4 November 2014 [

29]. In essence, Proposition 47 reduced prison terms for certain crimes. Similarly, the proposed policy would release prisoners early. However, Proposition 47 did not implement EM or any other steps to ensure that released prisoners would be deterred from committing new crimes—the releases are “naked”. In contrast, the proposed policy would implement EM plus home detention for all released prisoners, and would do so for the entire period of parole or probation. Thus, the proposed policy differs from Proposition 47 because it promises to protect society from 94.7 percent of the crime that would otherwise be committed by released prisoners.

Over 58 percent of California voters approved Proposition 47 [

29]. Thus, a substantial majority of voters approved reductions in prison terms—despite the absence of EM and home detention for released prisoners. Since the main argument opposing Proposition 47 involved concern about “naked” releases—the increase in crime that may be expected when prisoners are released early but not electronically monitored—one might expect that greater numbers of California voters would prefer the proposed policy, compared to Proposition 47, because the proposed policy would implement EM plus home detention and would promise to protect society from 94.7 percent of the crime that would otherwise be committed by released prisoners. This suggests that over 58 percent of California voters might support a ballot initiative to implement the proposed policy.

The impetus for Proposition 47 was the 2011 U.S. Supreme Court order requiring California to reduce its prison population. This pressure is not limited to California. Prison overcrowding is a perennial issue facing all states. Federal courts previously ordered several southern states to reduce overcrowding [

2]. Lacking the funds needed to build new prisons, state governments were forced to find alternatives to incarceration [

2]. The 2008 financial crisis caused economic activity and tax revenues to collapse, created a fiscal emergency, and created intense pressure to cut state expenditures, including expenditures on prisons. This renewed pressure on all states to find alternatives to incarceration. While economic activity and tax revenues have recovered, the impetus to find alternatives to incarceration remains strong because incarceration is now viewed as a costly, inefficient means to control crime.

Intense pressure to reduce prison populations and expenditures has undercut support for mass incarceration in conservative as well as liberal states. Policies similar to Proposition 47 have been implemented in both Texas and South Carolina, two conservative states [

29]. In 2013, 31 politically-diverse states adopted a total of 46 changes in sentencing policies that reduced prison terms and sought to reduce prison populations [

30].

Numerous states now permit sentences to be split. The initial portion of the sentence is served in prison and a subsequent portion is served on probation, outside prison, subject to various court-specified conditions. In some states, a court may order split sentencing at the commencement of the sentence, while in other states offenders must serve a portion of their sentences in prison before petitioning a court to be allowed to serve the remainder of their sentences on probation. The use of EM and home detention as a condition of probation has been limited but could easily be expanded.

Acceptance of split sentencing and early prisoner release is a major step toward the proposed policy. Therefore, it is highly significant that split sentencing—whether or not it is linked to EM and home detention—is available by statute in many states and has gained acceptance by courts and prosecutors in multiple jurisdictions. Florida allows split sentencing [

11]. New York allows split sentencing for certain crimes [

31]. California allows split sentencing [

32]. At least 14 states including Texas, Kentucky and Indiana allow “shock probation”, which is essentially equivalent to split sentencing, for certain crimes [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Oklahoma allows split sentencing [

37]. Wyoming allows split sentencing [

38]. Alabama allows split sentencing, with certain restrictions [

39]. North Carolina allows split sentencing [

40]. Ohio allows shock probation even for serious offenders [

33]. Oregon and Maine allow split sentencing [

41].

These changes in sentencing policies have allowed a third of all states to close prisons over the past three years—including North Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas [

30,

42]. Nearly two-thirds of all states have enacted reforms designed to reduce the number of inmates [

30,

42]. North Carolina closed six juvenile and adult facilities in 2013 [

2]. Keith Acree, at the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, noted that the state has closed a total of 16 prisons over the past eight years and observed, “There’s been no pushback at all….The only public or political opposition to the prison closures has come from some people losing their jobs or being reassigned” [

42].

Significantly, the changes in sentencing policies that permitted prison closures received support and were implemented despite the omission of the protections afforded by EM plus home detention. Therefore, the proposed policy—involving EM plus home detention—may be even more attractive to voters because it directly addresses the primary concern when prisoners are released early. This suggests the possibility that the proposed policy might garner broad national support. If the introduction of EM plus home detention throughout conventional periods of parole and probation reduces repeat crime by 94.7 percent, the proposed policy might elicit support from both liberal and conservative voters.

A national public opinion survey conducted in January 2012 indicates that the proposed policy might receive broad support from American voters. Across political parties and geographic regions, American voters support reductions in prison terms as long as released prisoners are supervised [

43]. Perhaps the most remarkable finding concerns violent offenders. By a margin of 67 percent to 26 percent, voters overwhelmingly prefer shorter sentences, followed by release and mandatory supervision, rather than full sentences followed by release without any supervision [

43]. The margin of support was large for Democrats (72 percent to 24 percent), Republicans (62 percent to 30 percent), voters who were members of a household that had experienced violent crime (68 percent to 24 percent), and voters who were members of a household that included a law enforcement officer (62 percent to 34 percent) [

43].

The pattern is repeated with regard to non-violent offenders. By a margin of 69 percent to 25 percent, voters overwhelmingly prefer shorter sentences, followed by release and mandatory supervision, rather than full sentences followed by release without any supervision [

43]. The margin of support was large for Democrats (72 percent to 23 percent), Republicans (67 percent to 26 percent), voters who were members of a household that had experienced violent crime (74 percent to 21 percent), and voters who were members of a household that included a law enforcement officer (67 percent to 28 percent) [

43].

In sum, both Democrats and Republicans support reforms that would release prisoners early but subject them to mandatory supervision [

43]. Significantly, 92 percent of voters agree that “An effective probation and parole system would use new technologies to monitor where offenders are and what they are doing, require them to pass drug tests, and require they either keep a job or perform community service” [

43]. Together, these results indicate broad support among both conservative and liberal voters for the type of reform that is proposed here.

8. SB 1410

Support for reform is being converted into legislative action at the national level. In January 2014, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee passed Senate Bill 1410, The Smarter Sentencing Act, a bipartisan bill that would revise federal mandatory sentencing guidelines for a variety of crimes in an effort to reduce the size of the current U.S. prison population and costs associated with it [

44]. The act has been described as the most significant legislative bill regarding criminal justice reform to reach the Senate floor in several years [

42]. The act reduces the length of mandatory sentences for drug related crimes. Twenty-year minimum sentences are reduced to 10 years, 10 year minimums to 5, and 5 year minimums to 2. The reductions apply to offenses covered under the Controlled Substances Act and Controlled Substance Import and Export Act involving marijuana, cocaine, heroin, PCP, LSD, methamphetamines, or a counterfeit of these substances. The act expands the ability of non-violent offenders to receive reduced sentences under the federal “safety valve”, which provides judicial discretion in assigning sentences below the federally established minimums to non-violent offenders with limited criminal histories [

44]. The act would also permit the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which eliminated the 5 year mandatory minimum sentence for first-time possession of crack cocaine, to be applied retroactively to currently incarcerated individuals who have not previously had their sentences decreased [

44]. This provision would give nearly 9000 inmates currently in prison for possession of crack cocaine an opportunity to have their sentences reduced [

2]. A similar bill exists in the House [

44]. Sponsored by Congressman Labrador (Republican from Idaho) and Congressman Scott (Democrat from Virginia), the bill contains the same sentencing changes for drug based offenses and transparency initiatives [

44].

The Smarter Sentencing Act was introduced as a cost-cutting measure by Senator Durbin (Democrat from Illinois) along with 31 bipartisan cosponsors to address the ballooning federal prison population, nearly half of which is incarcerated for drug offenses [

44]. The sponsors argued that the “changes could save taxpayers billions in the first years of enactment” [

44]. Significantly, Maplight.org lists 47 organizations that supported the bill including the American Bar Association, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Drug Policy Alliance, International Union of Police Associations, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP), while only three organizations opposed it [

45]. The amount of contributions given to Senators from interest groups that supported the bill was 18 times as large as the amount of contributions from interest groups that opposed the bill. The interest groups supporting the bill included groups representing women’s issues, Republican/conservative causes, minority/ethnic groups, state and local government employee unions, commercial service unions, welfare and social work organizations, health and welfare policy organizations, churches, clergy and religious organizations, labor unions, elected and appointed public officials, fiscal and tax policy organizations, human rights organizations, and consumer groups [

45]. Organizations representing police and firefighter unions and associations were split in their support of the bill [

45].

This indicates broad public support for reforms that reduce prison sentences. Broad support from influential interest groups translates into lopsided contributions to congressmen who support reform and translates into broad, bipartisan congressional support at the federal level. Opposition is limited to a small number of organizations, mainly representing peace officers, and the opposition is split.

9. The Tide Turns

The wave of states that have adopted sentencing reforms, the overwhelming support for the Smarter Sentencing Act, the results of the January 2012 national opinion survey, and the closure of prisons in numerous states suggest that support for mass incarceration has evaporated across the nation. A “tipping point” has been reached [

2]. “The paradigm of mass imprisonment is exhausted” ([

2], p. 18). The ideology of mass imprisonment is now viewed as bankrupt [

2]. Policymakers and the public are searching for alternatives. There is a consensus that mass incarceration is extremely expensive, bad social policy, and America incarcerates too many people, for too much time, at too much expense to taxpayers [

42,

46].

Intense pressure to cut state expenditures, widespread acknowledgement that mass incarceration is a failure, public demand for alternatives, and experience with multiple rounds of prison closures, changes in state sentencing policies, and reductions in prison sentences have opened the way for lawmakers, both liberal and conservative, to consider new strategies [

2,

42].

While a popular perception is that voters are fixated on policies to “get tough” on crime and are resistant to criminal justice reform, survey data suggest instead that the majority are pragmatic [

47]. They are open to new ideas and favor solutions to the problem of crime that go beyond incarceration [

43]. Americans favor reductions in sentences, early release of prisoners, and the use of cost-effective technology to supervise released prisoners, protect society, and protect offenders from the temptation to commit new crimes [

43].

Conservative leaders now reject mass incarceration. A “statement of principles” endorsed by 70 leading conservative figures emphasized that prison is not the solution for every type of offender:

Conservatives are known for being tough on crime, but we must also be tough on criminal justice spending. That means demanding more cost-effective approaches that enhance public safety. A clear example is our reliance on prisons, which serve a critical role by incapacitating dangerous offenders and career criminals but are not the solution for every type of offender

The statement reiterated a central principle: government services should be evaluated on whether they produce the best possible results at the lowest possible cost [

48]. The statement noted that heavy reliance on prisons is not cost-effective, emphasized the importance of “achieving a cost-effective system that protects citizens, restores victims, and reforms wrongdoers”, and opened the door to consideration of new strategies [

48].

Thus, the new narrative now focuses on cost-effective, research-based strategies to improve public safety [

2]. This has translated into increased receptiveness of Democratic and Republican state leaders to new ideas and a willingness to adopt research-based strategies that are more effective and less expensive than incarceration: “evidence-based corrections has arrived” ([

2], p. 19). The emphasis on research evidence now permeates the discourse surrounding criminal justice reform at both state and federal levels. The new emphasis on research evidence and cost-efficiency is illustrated by a joint program between the Justice Department and civil society titled the “Justice Reinvestment Initiative” [

42]. Since 2010, this program has sought to “identify and implement cost-efficient, evidence-based criminal justice reforms” [

42].

While the movement has been driven by the imperative to reduce prison expenditures, the emphasis on research evidence and cost-effectiveness aligns with deeply-rooted American values and a strong desire for government efficiency—as illustrated by the statement of principles enunciated by 70 leading conservative figures [

48]. Furthermore, as noted by Joan Petersilia and Francis Cullen, “once science is embraced as a criterion for decision-making, a retreat from knowing ‘what the evidence says’ is difficult” ([

2], p. 19). Research evidence is now a staple of conversations held with policymakers pursuing criminal justice reform [

49].

This does not imply that policy is normally guided by research evidence or would be guided by the evidence presented here. However, the analysis suggests why the research reported here, and why the proposal to release prisoners early but require EM plus home detention, may neatly align with fiscal imperatives to cut state and federal expenditures on prisons, judicial pressure to eliminate prison overcrowding, public opinion that favors early prisoner releases linked to technology-enhanced mandatory parole supervision, momentum at the state and federal levels to revise sentencing guidelines and embrace cost-effective alternatives to incarceration, broad recognition that mass incarceration has failed, and the hunger for cost-effective, evidence-based reforms that protect society and protect offenders from the temptation to commit new crimes.

10. Stakeholder Analysis

A question that arises is why the proposed policy has not already been implemented. If the proposal is sound and circumstances are ripe for change, what has prevented implementation? One possibility is lack of awareness that a cost-effective solution exists to the problem of crime. Even within the small circle of criminal justice scholars, awareness of the proposed policy and the research supporting it appears to be limited. This is compounded by a perception that electronic monitoring has been tried, evaluated and found to be overrated, warnings that true reform will require costly investments in rehabilitation services, and caution about accepting the Padgett

et al. results [

2,

27,

28]. Ultimately, stakeholders with regard to criminal justice reform will need to decide whether any of the alternative strategies for fighting crime, or the option of standing pat and waiting for additional evidence, is more promising than the proposal that is offered here. Each option offers risks. Only the stakeholders can decide what option to pursue.

Assuming, however, that the option of standing pat is not attractive, what reason is there to think that the legislative gridlock that characterizes Washington, DC can be overcome? What reason is there to think that the American policy process, driven by partisan interests and controlled by powerful lobbying groups, would ever coalesce around the proposed policy—a policy that is billed as rational and cost-effective but is otherwise wonkish and difficult to capture in a sound bite? The answer to this question requires answers to several other questions. Who are the stakeholders with regard to criminal justice reform? What are their interests and concerns? What would be their likely responses to the proposed policy?

The stakeholders, their preferences, and their likely responses to the proposed policy may be inferred from the list of organizations that took a position on SB 1410, the Smarter Sentencing Act of 2014. The 47 organizations that supported this bill included organizations concerned with criminal justice policy and human rights: the American Bar Association, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, American Probation and Parole Association, Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, Community Action Partnership, Council on American-Islamic Relations, Drug Policy Alliance, Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, Gamaliel Foundation, Heritage Action for America, Human Rights Watch, International Community Corrections Association, International Union of Police Associations, Japanese American Citizens League, Jewish Council for Public Affairs, Lawyers’ Committee For Civil Rights Under Law, Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, League of Women Voters, National Action Network, National Association of Evangelicals, National Association of Social Workers, National Council of La Raza, National Employment Law Project, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, Unitarian Universalist Association, and the United Methodist Church, General Board of Church and Society [

45]. These stakeholders might respond to the appeal of the proposed policy as a promising strategy to reform the criminal justice system, improve public safety and improve the treatment of individuals convicted of crimes. Notably, this list of organizations included the American Probation and Parole Association and the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, indicating broad support even among groups that might be expected to oppose SB 1410.

A second set of stakeholders that supported SB 1410 involves organizations that advocate for the rights of convicted individuals: Justice Strategies, Prison Policy Initiative, R Street Institute, Sentencing Project, StoptheDrugWar.org, Students for Sensible Drug Policy, CURE-Women Incarcerated, Families against Mandatory Minimums, OurTime.org, and Prison Fellowship [

45]. These stakeholders might respond to the appeal of the proposed policy as a promising strategy to improve the treatment of individuals convicted of crimes.

A third set of stakeholders that supported SB 1410 involves organizations that advocate for the advancement of black Americans, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the National Urban League [

45]. While 100 Black Men of America is not listed as a financial contributor in support of SB 1410, it is generally aligned in support of sentencing reform. These stakeholders might respond to the appeal of the proposed policy as a promising strategy to redress the enormous imbalance in the incarceration rates of blacks, compared to whites.

A fourth set of stakeholders that supported SB 1410 includes powerful mainstream organizations that represent the broad interests of large segments of American society: the AFL-CIO, American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, Americans for Tax Reform, the Coalition to Reduce Spending, the Service Employees International Union, and the Taxpayers Protection Alliance [

45]. These stakeholders might respond to the appeal of the proposed policy as a promising strategy to reduce taxes, reduce expenditures on prisons, and protect society.

Significantly, these stakeholders supported SB 1410 despite the omission of the protections afforded by EM plus home detention. Therefore, the proposed policy—involving EM plus home detention—may be even more attractive to these stakeholders, because the proposed policy directly addresses the primary concern when prisoners are released early. This suggests the possibility that the proposed policy might garner broad national support. If the introduction of EM plus home detention throughout conventional periods of parole and probation reduces repeat crime by 94.7 percent, the proposed policy might elicit support from all of the stakeholders that supported SB 1410.

The three organizations that opposed SB 1410 were the National Association of Assistant United States Attorneys, the National Association of Police Organizations, and the National Narcotics Officers’ Associations’ Coalition. It is notable that victims’ rights organizations were not listed as opponents of SB 1410—suggesting that they were not opposed. However, it may be presumed that all of these groups were concerned about the potential increase in crime associated with reduced sentences, and all of these groups might be attracted to the proposed policy because it directly addresses the primary concern when prisoners are released early.

Other organizations that were not listed as contributors supporting the passage of SB 1410, but may respond to the appeal of the proposed policy as a promising strategy to reform the criminal justice system, improve public safety and improve the treatment of individuals convicted of crimes, include: Amnesty International, Human Rights First, US Human Rights Network, The Pew Center on the States Public Safety Project, Vera Institute of Justice, Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice, the Open Society Policy Center, the Council of State Governments Justice Center, Nation Inside, Reentry Central, Solitary Watch, the Innocence Project, Just Detention International, the Prison Activist Resource Center, the Women’s Prison Association, the California Coalition for Women Prisoners, Children of Inmates, Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, Reclaiming Futures National Program Office, the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the National Governors Association (NGA), the National Business Association, and the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP). Governors may be expected to support the proposed policy because this strategy promises to greatly reduce crime, increase public safety and reduce government expenditures on prisons and corrections, thereby reducing taxes. The National Business Association may be expected to support the proposed policy because the strategy promises to reduce crime, reduce government expenditures on prisons and corrections, and reduce taxes. The American Association of Retired Persons may be expected to support the proposed policy because it promises to greatly reduce crime, including crime committed against retired persons; increase public safety, especially for retired persons; and reduce taxes that are especially onerous for retired persons living on fixed incomes.

This suggests the possibility that a broad coalition, representing the interests of many Americans, could be constructed with the goal of influencing public policy. An organized campaign that recruited the support of these stakeholders, built a coalition representing the broad interests of large segments of American society and appealed to American values of fairness, justice, and efficiency and promised real change could potentially be successful in achieving the changes in state and federal laws that would be necessary to implement the proposed policy regarding EM and home detention. This perspective suggests reason for optimism.

Stakeholders who might oppose the proposed policy might include the same stakeholders who opposed California Proposition 47: police and police chiefs, sheriffs, corrections officers, and district attorneys. However, since the proposed policy includes EM plus home detention, in contrast to Proposition 47, the proposed policy is potentially more attractive to peace officers and district attorneys because EM plus home detention promises to protect society from 94.7 percent of the crime that would otherwise be committed by released prisoners. Furthermore, the proposed policy—unlike Proposition 47—does not reduce certain felonies to misdemeanors. In any case, the outcome of the Proposition 47 ballot initiative, where over 58 percent of voters approved the initiative and rejected arguments in opposition, suggests that opposition to the proposed policy could be overcome.

The proposed policy might be attractive to peace officers, district attorneys and victims’ rights associations because it offers perhaps the only practical means of requiring offenders to serve out their full sentences. The proposed policy envisions that offenders would serve the first half of their sentences in prison, while the second half would be served in the form of EM plus home detention. Historically, offenders have served approximately half of their sentences in prison but have then been released on parole without EM and without home detention ([

3], p. 58). The Padgett

et al. study indicates that EM plus home detention during the second half of each sentence is nearly as effective as locking prisoners in a maximum security prison. Thus, society would receive nearly the same level of protection as would be the case if all prisoners served out their full sentences in a maximum security prison.

The proposed policy might be attractive to peace officers, district attorneys and victims’ rights groups because it offers perhaps the only practical means of complying with mandates to reduce prison overcrowding while maintaining tight control over released prisoners. California was forced to reduce overcrowding by order of the US Supreme Court and had to release thousands of prisoners [

50,

51]. Those prisoners may have been placed on parole or probation, but were not supervised through EM and home detention. The proposed policy would permit states such as California to comply with mandates to reduce overcrowding and release prisoners from prison but maintain a level of control over released prisoners that deters 94.7 percent of the crime that would otherwise occur.

The proposed policy might be attractive to judges who must consider the possible impact of early prisoner releases on society, as well as on their chances of re-election. When prisoners are released early but commit new crimes, judges are vulnerable to charges by their opponents that they are “soft on crime” and may be replaced at the next election. Former District and Circuit Court Judge Thomas Knopf expressed the anxiety that he felt as a judge whenever he contemplated a decision regarding early prisoner release: “I think it’s one of the more difficult decisions…[if you] make a bad decision [and] you let someone out that would cause other havoc or crimes, you’ll answer for it” [

52]. The ability to impose EM plus home detention could make early prisoner releases more acceptable by alleviating concerns that early releases would contribute to an increase in crime.

11. Legislation

While changes in state law could be achieved with a ballot initiative, such campaigns are labor-intensive and require the investment of substantial resources. An alternative route would involve securing the cooperation of state legislators who are willing to sponsor and support the passage of legislation that would implement the proposed policy. If bipartisan sponsorship could be secured from Democratic and Republican legislators, this route might be quicker and easier than a ballot initiative. The challenge is to translate the proposed policy into legislation by building a coalition of influential advocates regarding the policy issue and the proposed solution, identifying key legislators and government officials, and creating a public litmus test of their support for the proposed policy.

The first step would be to identify key legislators and legislative staff members who control legislative bills concerning criminal justice reform. Key legislators might include Assembly, House or Senate members and staff members of corrections committees, prison reform committees, judiciary committees and similar committees.

Once key decision-makers are identified, it would be necessary to gain their support. In general, this would require a demonstration that there is a higher level of support among constituents who favor the proposed policy, compared to those who may be opposed. This demonstration could be accomplished by building a vocal coalition of advocates for the proposed policy, securing letters of support, and organizing petitions that demonstrate the support of large numbers of constituents.

An effective strategy might employ the use of online petitions to create public litmus tests and compel the support of key decision-makers for the proposed policy. Petitions serve to demonstrate support from large numbers of individuals who have the power to vote public officials out of office at the next election. While traditional petitions require the investment of large resources, online petitions are relatively easy to initiate, enabling social activists to quickly mobilize large numbers of citizens despite limited resources (see, for example, Change.org, MoveOn.org, Petition.org and Petitionsite.com). Petitions directed to key legislative decision-makers could compel votes to pass legislative bills out of committee, bring bills to the floor for voting, and compel support for the final bills.

12. Conclusions

This article has proposed a change in public policy that offers to greatly reduce major crime in the United States, protect society, eliminate prison overcrowding, and save taxpayer dollars. In addition, the article offers a theory of policy change and a stakeholder analysis that seeks to explain how this change in policy might be accomplished, either through ballot initiatives or through legislation sponsored by state legislators, despite the legislative gridlock that characterizes the state and federal policy process. A highly visible, concerted effort by a coalition of criminal justice activists employing online petitions and a network of activists to mobilize a large mass of supporters could potentially generate a highly-public, intense mail campaign targeted to key decision-makers, create public litmus tests of their support for reform, galvanize action, and achieve the proposed reform of criminal justice policies.

While current paradigmatic assumptions appear to exclude consideration of EM and home detention as a promising strategy, EM and home detention have been successfully implemented in Britain and in Florida. This strategy has been found to be practical, effective, cost-effective, ethical and humane. Padgett

et al.’s results suggest that the proposed policy would avert 94.7 percent of the crimes typically committed by parolees and probationers [

11]. The total cost of monitoring each offender would be $20.37 per day [

17]. It is doubtful that there is another strategy for reducing crime that is more effective, at lower cost.

The analysis reported here suggests that EM and home detention represent a highly-effective but underutilized approach for reducing crime, protecting society, and reforming the criminal justice system. The challenge is that EM—which lacks a treatment component, does not address unemployment and poverty, and does not add boots on the ground—fails to fit into the existing paradigm. EM fails to fit into theories that crime is a problem of weak enforcement, a problem of intrapersonal psychology, or a problem of poverty and unemployment. EM and home detention represent a completely different view about why crime exists and what works in controlling it. However, if this view is correct, it may be possible to deter much of the crime that is committed by repeat offenders, protect society, and achieve this result through the use of technology that is cost-effective and well-understood.