Alicyclobacillus spp.: New Insights on Ecology and Preserving Food Quality through New Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction: The General Traits of Alicyclobacillus spp.

| Species | Source of Isolation | Temp. Range (°C) | Optimum Temperature (°C) | pH Range | Optimum pH | ω-Cyclohexane/ω-Cicloheptane Fatty Acids | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. acidiphilus | acidic beverages | 20–55 | 50 | 2.5–5.5 | 3.0 | ω-cyclohexane | [10] |

| A. acidocaldarius | soil, fruits, syrup | 35–70 | 55–60 | 2.5–6.0 | 4.5 | ω-cyclohexane | [2] |

| A. acidoterrestris | soil, acidic beverages | 20–55 | 40–50 | 2.0–6.0 | 3.5–4.5 | ω-cyclohexane | [2] |

| A. aeris | copper mine | 25–35 | 30 | 2.0–6.0 | 3.5 | none | [11] |

| A. cellulosilyticus | cedar chips | 40.0–67.5 | 55 | 3.5–6.5 | 4.8 | ω-cyclohexane | [12] |

| A. contaminans | juices | 35–60 | 50–55 | 3.0–6.0 | 4.0–4.5 | none | [13] |

| A. cycloheptanicus | soil | 30–55 | 50 | 3.0–5.5 | 4.0 | ω-cycloheptane | [2] |

| A. dauci | spoiled mixed juice | 20–50 | 40 | 3.0–6.0 | 4.0 | ω-cyclohexane | [14] |

| A. disulfidooxidans | wastewater sludge | 04–40 | 35 | 0.5–6.0 | 1.5–2.5 | ω-cyclohexane | [15] |

| A. fastidiosus | soil, beverages | 20–55 | 40–45 | 2.0–5.5 | 4.0–4.5 | ω-cyclohexane | [13] |

| A. ferrooxydans | solfataric soil | 17–40 | 28 | 2.0–6.0 | 3.0 | none | [16] |

| A. herbarius | herbal tea | 35–65 | 55–60 | 3.5–6.0 | 4.5–5.0 | ω-cycloheptane | [17] |

| A. hesperidum | solfataric soil | 35–60 | 50–53 | 2.5–5.5 | 3.5–4.0 | ω-cyclohexane | [18] |

| A. kakegawensis | soil | 40–60 | 50–55 | 3.0–6.5 | 4.0–4.5 | ω-cycloheptane | [13] |

| A. macrosporangiidus | beverages, environments | 35–60 | 50–55 | 3.0–6.5 | 4.0–4.5 | none | [13] |

| A. pomorum | fruits | 30–60 | 45–50 | 2.5–6.5 | 4.5–5.0 | none | [19] |

| A. sacchari | sugar | 30–55 | 45–50 | 2.0–6.0 | 4.0–4.5 | ω-cyclohexane | [13] |

| A. sendaiensis | soil | 40–65 | 55 | 2.5–6.5 | 5.5 | ω-cyclohexane | [20] |

| A. shizuokaensis | soil | 35–60 | 45–50 | 3.0–6.5 | 4.0–4.5 | ω-cycloheptane | [13] |

| A. tengchongensis | hot spring soil | 30–50 | 45 | 2.0–6.0 | 3.2 | ω-cycloheptane | [21] |

| A. tolerans | solfataric soil | 20–55 | 37–42 | 1.5–5.0 | 2.5–2.7 | ω-cyclohexane | [15] |

| A. vulcanalis | geothermal pool | 35–65 | 55 | 2.0–6.0 | 4.0 | ω-cyclohexane | [22] |

2. Characteristic of Alicyclobacillus spp.

| Species | DNA G + C Content (%) | Homology with 16S rRNA of Some Other Species of the Genus | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. acidiphilus | 54.1 | A. acidoterrestris (96.6%) | [10] |

| A. acidocaldarius | 61.89 | A. acidoterrestris (98.8%) | [30] |

| A. acidoterrestris | 51.5 | A. acidocaldarius (98.8%) | [2] |

| A. aeris | 51.2 | A. ferrooxydans (94.2%) | [11] |

| A. cellulosilyticus | 60.8 | A. macrosporangiidus (91.9%) | [12] |

| A. contaminans | 61.1–61.6 | Alicyclobacillus (92.3%–94.6%) | [13] |

| A. cycloheptanicus | 57.2 | Alicyclobacillus (92.7%–93.2%) | [2] |

| A. dauci | 49.6 | A. acidoterrestris (97.4%) and A. fastidiosus (97.3%) | [14] |

| A. disulfidooxidans | 53 | A. tolerans (92.6%) | [15] |

| A. fastidiosus | 53.9 | Alicyclobacillus (92.3%–94.6%) | [13] |

| A. ferrooxydans | 48.6 | A. pomorum (94.8%) | [16] |

| A. herbarius | 56.2 | Alicyclobacillus (91.3%–92.6%) and Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans (84.7%) | [17] |

| A. hesperidum | 60.3 | Alicyclobacillus (97.7%–98%) | [18] |

| A. kakegawensis | 61.3–61.7 | Alicyclobacillus (92.3%–94.6%) | [13] |

| A. macrosporangiidus | 62.5 | Alicyclobacillus (92.3%–94.6%) | [13] |

| A. pomorum | 53.1 | Alicyclobacillus (92.5%–95.5%) | [19] |

| A. sacchari | 56.6 | Alicyclobacillus (92.3%–94.6%) | [13] |

| A. sendaiensis | 62.3 | A. vulcanis (96.9%) | [22] |

| A. shizuokaensis | 60.5 | Alicyclobacillus (92.3%–94.6%) | [13] |

| A. tengchongensis | 53.7 | Alicyclobacillus (90.3%–92.8%) | [21] |

| A. tolerans | 48.7 | Alicyclobacillus (92.1%–94.6%) and S. thermosulfidooxidans (87.7%) | [15] |

| A. vulcanalis | 62 | A. acidocaldarius (97.8%) | [22] |

- Lower number of charged residues. The α-amylases extracted from Alicyclobacillus spp. contain ca. 30% fewer charged residues than their closest relatives.

- Acidic and basic residues. More basic residues are exposed on the surface, whereas the acidic groups are buried on the interior.

- Salt bridges. Pechkova et al. [42] reported that an increase number of salt bridges results in greater compactness of the structure and thereby contributes to thermostability.

- Cavities. Proteins from alicyclobacilli are more closely packed than the analogue molecules in mesophiles.

- Proline. Thermostable proteins by alicyclobacilli show a higher content of proline and this amino acid is more common at the second position of the β-turns.

3. Ecology of the Genus Alicyclobacillus, with a Special Focus on the Species A. acidoterrestris

| Method | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Lipase and esterase fingerprints | Juice incubation at 45 °C for 24 h, cell harvesting and chromatography | [60] |

| Aptamer-based enrichment 16S rDNA | The method requires a preliminary enrichment step, so it can take up to 1 week. After a mechanical treatment, DNA was quantified through a RT-PCR based approach | [61] |

| Immunomagnetic separation RT-PCR | Immunomagnetic separation was combined with RT-PCR, by using two probes. The method is highly selective for A. acidoterrestris | [38] |

| FIR | Fourier transformed intra-red spectroscopy (1350–1700/cm), combined with multivariate statistical analysis (Principal Component Analysis and Class Analogy), allows the discrimination between Bacillus and Alicyclobacillus spp. | [62] |

| G-quadruplex colorimetric method | A. acidoterrestris was grown at 45 °C in presence of vanillic acid; this compound is easily converted to guaiacol and finally to tetraguaiacol (amber-coloured). The reaction is catalysed by G-quadruplex DNA-zyme | [63] |

| DAS-ELISA | DAS-ELISA (double antibodies sandwich ELISA) assay is based on the two kinds of polyclonal antibodies from Japanese White rabbit. The method shows high sensitivity and excellent agreement with isolation by K medium | [64] |

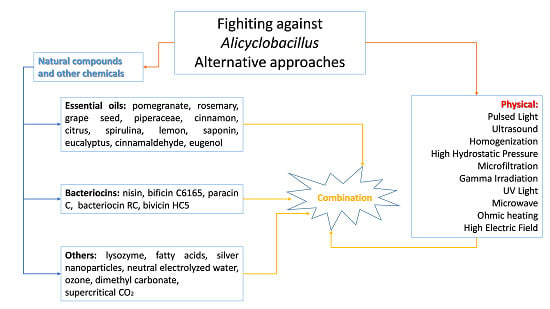

4. Alternative Approaches to Mitigate Alicyclobacillus Species Associated with Food Spoilage

- determination of D-value and z-value of A. acidoterrestris spores;

- potential for A. acidoterrestris spore growth during product storage for at least 1 month at 25 and 43 °C;

- quality during storage following pasteurization treatments of different severity.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da Costa, M.S.; Rainey, F.A. Family II. Alicyclobacillaceae fam. nov. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed.; De Vos, P., Garrity, G., Jones, D., Krieg, N.R., Ludwig, W., Rainey, F.A., Schleifer, K.H., Whitman, W.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 3, p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Wisotzkey, J.D.; Jurtshuk, P.; Fox, G.E.; Deinhart, G.; Poralla, K. Comparative sequence analyses on the 16S rRNA (rRNA) of Bacillus acidocaldarius, Bacillus acidoterrestris, and Bacillus cycloheptanicus and proposal for creation of a new genus, Alicyclobacillus gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992, 42, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, I.; Chuyate, R. Alicyclobacillus—Historical perspective and preliminary characterization study. Dairy Food Environ. Sanit. 1998, 18, 499–503. [Google Scholar]

- Tourova, T.P.; Poltoraus, A.B.; Lebedeva, I.A.; Tsaplina, I.A.; Bogdanova, T.I.; Karavaiko, G.I. 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequence analysis and phylogenetic position of Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1994, 17, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, P. Primary structure of the 16S rRNA gene of Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans by direct sequencing of PCR amplified gene and its similarity with that of other moderately thermophilic chemolithotrophic bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1996, 19, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, M.; Ariga, T. ω-Cyclohexyl fatty acids in acidophilic thermophilic bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 6963–6968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hippchen, B.; Roőll, A.; Poralla, K. Occurrence in soil of thermo-acidophilic bacilli possessing ω-cyclohexane fatty acids and hopanoids. Arch. Microbiol. 1981, 129, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.S.; Kang, D.H. Alicyclobacillus spp. in the fruit juice industry: History, characteristics, and current isolation/detection procedures. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 30, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiroa, M.N.U.; Junquera, V.C.A.; Schmidt, F.L. Alicyclobacillus in orange juice: Occurrence and heat resistance of spores. J. Food Protect. 1999, 62, 883–886. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, H.; Goto, K.; Matsumura, T.; Mochida, K.; Iwaki, M.; Niwa, M.; Yamasoto, K. Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus sp. nov., a novel thermo-acidophilic, ω-alicyclic fatty acid-containing bacterium isolated from acidic beverages. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; You, X.Y.; Liu, L.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, S.J.; Jiang, C.Y. Alicyclobacillus aeris sp. nov., a novel ferrous- and sulphur-oxidizing bacterium isolated from a copper mine. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2415–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusube, M.; Sugihara, A.; Moriwaki, Y.; Ueoka, T.; Shimane, Y.; Minegishi, H. Alicyclobacillus cellulosilyticus sp. nov., a thermophilic, cellulolytic bacterium isolated from steamed Japanese cedar chips from a lumbermill. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2257–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K.; Mochida, K.; Kato, Y.; Asahara, M.; Fujita, R.; An, S.Y.; Kasai, H.; Yokota, A. Proposal of six species of moderately thermophilic, acidophilic, endospore-forming bacteria: Alicyclobacillus contaminans sp. nov., Alicyclobacillus fastidiosus sp. nov., Alicyclobacillus kakegawensis sp. nov., Alicyclobacillus macrosporangiidus sp. nov., Alicyclobacillus sacchari sp. nov. and Alicyclobacillus shizuokensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakano, C.; Takahashi, N.; Tanaka, N.; Okada, S. Alicyclobacillus dauci sp. nov., a slightly thermophilic, acidophilic bacterium isolated from a spoiled mixed vegetable and fruit juice product. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavaiko, G.I.; Bogdanova, T.I.; Tourova, T.P.; Kondrat’eva, T.F.; Tsaplina, I.A.; Egorova, M.A.; Krasil’nikova, E.N.; Zakharchuk, L.M. Reclassification of “Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans subsp. thermotolerans” strain K1 as Alicyclobacillus tolerans sp. nov. and Sulfobacillus disulfidooxidans Dufresne et al. 1996 as Alicyclobacillus disulfidooxidans comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Alicyclobacillus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; You, X.Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, S.J. Alicyclobacillus ferrooxydans sp. nov., a ferrous-oxidizing bacterium from solfataric soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2898–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K.; Matsubara, H.; Mochida, K.; Matsumura, T.; Hara, Y.; Niwa, M.; Yamasato, K. Alicyclobacillus herbarius sp. nov., a novel bacterium containing ω-cycloheptane fatty acids, isolated from herbal tea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, L.; Rainey, F.A.; Chung, A.P.; Sunna, A.; Nobre, M.F.; Grote, R.; Antranikian, G.; da Costa, M.S. Alicyclobacillus hesperidum sp. nov. and a related genomic species from solfataric soils of São Miguel in the Azores. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K.; Mochida, K.; Asahara, M.; Suzuki, M.; Kasai, H.; Yokota, A. Alicyclobacillus pomorum sp. nov., a novel thermo-acidophilic, endospore-forming bacterium that does not possess ω-alicyclic fatty acids, and emended description of the genus Alicyclobacillus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruoka, N.; Isono, Y.; Shida, O.; Hemmi, H.; Nakayama, T.; Nishino, T. Alicyclobacillus sendaiensis sp. nov., a novel acidophilic, slightly thermophilic species isolated from soil in Sendai, Japan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.G.; Lee, J.C.; Park, D.J.; Li, W.J.; Kim, C.J. Alicyclobacillus tengchongensis sp. nov., a thermo-acidophilic bacterium isolated from hot spring soil. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simbahan, J.; Drijber, R.; Blum, P. Alicyclobacillus vulcanalis sp. nov., a thermophilic, acidophilic bacterium isolated from Coso Hot Springs, California, USA. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1703–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deinhard, G.; Saar, J.; Krischke, W.; Poralla, K. Bacillus cycloheptanicus sp. nov., a new thermophile containing ω-cycloheptane fatty acids. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1987, 10, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, S.P.; Falsen, E.; Martin, K.; Kämpfe, P. Alicyclobacillus consociatus sp. nov., isolated from a human clinical specimen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3623–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poralla, K.; Kannenberg, E.; Blume, A. A glycolipid containing hopane isolated from the acidophilic, thermophilic Bacillus acidocaldarius, has a cholesterol-like function in membranes. FEBS Lett. 1980, 113, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannenberg, E.; Blume, A.; Poralla, K. Properties of ω-cyclohexane fatty acids in membranes. FEBS Lett. 1984, 172, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, N. Alicyclobacillus—A new challenge for the food industry. Food Aust. 1999, 51, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, K.; Saito, K.; Kawaguchi, A.; Okuda, S.; Komagata, K. Occurrence of ω-cyclohexyl fatty acids in Curtobacterium pusillum strains. J. Appl. Gen. 1981, 27, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusano, K.; Yamada, H.; Niwa, M.; Yamasato, K. Propionibacterium cyclohexanicum sp. nov., a new acid-tolerant ω-cyclohexyl fatty acid-containing propionibacterium isolated from spoiled orange juice. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997, 47, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavromatis, K.; Sikorski, J.; Lapidus, A.; del Rio, T.G.; Copeland, A.; Tice, H.; Cheng, J.F.; Lucas, S.; Chen, F.; Nolan, M.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius type strain (104-IAT). Stand. Genom. Sci. 2010, 2, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.; Phillips, C.A. Original article Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris: An increasing threat to the fruit juice industry? Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris: New methods for inhibiting spore germination. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennis, R.B. Respiration in archaea and bacteria: Diversity of prokaryotic electron transport carriers. In Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, 2nd ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 83, pp. 363–364. [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh, M.; Pasvolsky, R.; Zakin, V. External pH is a cue for the behavioral switch that determines surface motility and biofilm formation of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1418–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Anjos, M.M.; Ruiz, S.P.; Nakamura, C.V.; de Abreu, F.; Alves, B. Resistance of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores and biofilm to industrial sanitizers. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1408–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, A.; Walsh, G. Characterisation of a novel thermostable endoglucanase from Alicyclobacillus vulcanalis of potential application in bioethanol production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 7515–7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennacchio, A.; Mandrich, L.; Manco, G.; Trincone, A. Enlarging the substrate portfolio of the thermophilic esterase EST2 from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius. Extremophiles 2015, 19, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, R.; Yuan, Y.; Niu, C.; Hu, Z.; Yue, T. An immunomagnetic separation-real-time PCR system for the detection of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in fruit products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 175, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Liu, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, L.; Xue, D.; Jiang, B.; Mu, W. Biochemical characterization of a thermostable l-arabinose isomerase from a thermoacidophilic bacterium, Alicyclobacillus hesperidum URH17-3-68. J. Mol. Catal. Enzym. 2014, 102, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, Y. α-Amylase (AmyP) of glycoside hydrolase subfamily GH13_37 is resistant to various toxic compounds. J. Mol. Catal. Enzym. 2013, 98, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Corbo, M.R. Characterization of a wild strain of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris: Heat resistance and implications for tomato juice. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, M130–M136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechkova, E.; Sivozhelezov, V.; Nicolini, C. Protein thermal stability: The role of protein structure and aqueous environment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 466, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Hatab, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yue, T. Patulin reduction in apple juice by inactivated Alicyclobacillus spp. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerny, G.; Hennlich, W.; Poralla, K. Fruchtsaftverderb durch Bacillen: Isolierung und charakterisierung des verderbserrengers. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1984, 179, 224–227. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Splittstoesser, D.F.; Churey, J.J.; Lee, Y. Growth characteristics of aciduric sporeforming Bacilli isolated from fruit juices. J. Food Prot. 1994, 57, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, N.; Whitfield, F.B. Role of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in the development of a disinfectant taint in shelf-stable fruit juice. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 36, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, K.; Teduka, H.; Shinano, H. Isolation and identification of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris from acidic beverages. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1996, 60, 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettipher, G.L.; Osmundsen, M.E.; Murphy, J.M. Methods for the detection, enumeration and identification of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris and investigation of growth and production of taint in fruit juice-containing drinks. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1997, 24, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, H.A.; Jensen, N. Spoilage of iced tea by Alicyclobacillus. Food Aust. 2000, 52, 292. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, W.G.; Gouws, P.A.; Witthuhn, R.C. Isolation, identification and typification of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris and Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius strains from orchard soil and the fruit processing environment in South Africa. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, S.; Ikawa, J.Y.; Parkinson, N.; Haglund, J.; Lee, J. Characteristics of an acidophilic Bacillus strain isolated from shelf-stable juices. J. Food Prot. 1995, 58, 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Oteiza, J.M.; Soto, S.; Alvarenga, V.O.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Giannuzzi, L. Flavorings as new sources of contamination by deteriogenic Alicyclobacillus of fruit juices and beverages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 172, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.V.M.; Gibbs, P. Target selection in designing pasteurization processes for shelf-stable high-acid fruit products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegmund, B.; Pöllinger-Zierler, B. Growth behavior of off-flavor-forming microorganisms in apple juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6692–6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahçeci, K.S.; Gokmen, V.; Acar, J. Formation of guaiacol from vanillin by Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in apple juice: A model study. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 220, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Nishibori, Y.; Wasada, K.; Furuhata, M.; Fukuyama, M.; Hara, Y. Identification of thermo-acidophilic bacteria isolated from the soil of several Japanese fruit orchards. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlinghaus, A.; Engel, R. Alicyclobacillus incidence in commercial apple juice concentrate (AJC) supplies-method development and validation. Fruit Process. 1997, 7, 262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M.; Kojima, H.; Fukui, M. Proposal of Effusibacillus lacus gen. nov. sp. nov., and reclassification of Alicyclobacillus pohliae as Effusibacillus pohliae comb. nov. and Alicyclobacillus consociatus as Effusibacillus consociatus comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2770–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.L. Control of bacterial spores. Br. Med. Bull. 2000, 56, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, R.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yue, T. Discrimination of Alicyclobacillus Strains by Lipase and Esterase Fingerprints. Food Anal. Method 2015, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hünniger, T.; Felbinger, C.; Wessels, H.; Mast, S.; Hoffmann, A.; Schefer, A.; Märtlbauer, E.; Paschke-Kratzin, A.; Fischer, M. Food Targeting: A real-time PCR assay targeting 16S rDNA for direct quantification of Alicyclobacillus spp. spores after aptamer-based enrichment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 4291–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Holy, M.A.; Lin, M.; Alhaj, O.A.; Abu-Goush, M.H. Discrimination between Bacillus and Alicyclobacillus isolates in apple juice by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, M399–M404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.A. G-quadruplex DNAzyme-based colorimetric method for facile detection of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris. Analyst 2014, 139, 4315–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Huang, R.; Xia, K.; Liu, L. Double antibodies sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in apple juice concentrate. Food Control 2014, 40, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Irradiation in the production, processing and handling of food. Final rule. Fed. Regist. 2012, 77, 71312–71316. [Google Scholar]

- Lado, B.H.; Yousef, A.E. Alternative food-preservation technologies: Efficacy and mechanisms. Microb. Infect. 2002, 4, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, A.; Rodrigo, D.; Martínez, A.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Rodrigo, M. Effect of PEF and heat pasteurization on the physical–chemical characteristics of blended orange and carrot-juice. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.H.; Nielsen, S.S. The effect of thermal and non-thermal processing methods on apple cider quality and consumer acceptability. J. Food Qual. 2005, 28, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R.V.; Beuchat, L.R. Efficiency of disinfectants in killing spores of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris and performance of media for supporting colony development by survivors. J. Food Prot. 2002, 63, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.V.M.; Gibbs, P. Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores in fruit products and design of pasteurization processes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianli, Y.; Jiangbo, Z.; Yahong, Y. Spoilage by Alicyclobacillus Bacteria in Juice and Beverage Products: Chemical, Physical, and Combined Control Methods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 771–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Barrientos, J.U.; Wang, Q.; Markland, S.M.; Churey, J.J.; Padilla-Zakour, O.I.; Worobo, R.W.; Kniel, K.E.; Moraru, C.I. Efficient Reduction of Pathogenic and Spoilage Microorganisms from Apple Cider by Combining Microfiltration with UV Treatment. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysal, A.H.D.; Ünlütürk, S. Short wave ultraviolet light (UVC) disinfection of surface—Inhibition of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores on agar medium. VTT Symp. 2008, 251, 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Cibelli, F.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Effects of high pressur homogenization on the survival of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores in a laboratory medium. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Harte, F.M.; Davidson, P.M.; Golden, D.A. Inactivation of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris using high pressure homogenization and dimethyl dicarbonate. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannini, L.; Lanciotti, R.; Baldi, D.; Guerzoni, M.E. Interactions between high pressure homogenization and antimicrobial activity of lysozyme and lactoperoxidase. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gongora-Nieto, M.M.; Sepùlveda, D.R.; Pedrow, P.; Barbarosa-Cànovas, G.V.; Swanson, B.G. Food Processing by Pulsed Electric Fields: Treatment Delivery, Inactivation Level and Regulatory Aspects. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.T.; Zhang, Q.H. Pulsed electric field inactivation of microorganisms and preservation of quality of cranberry juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 1999, 23, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-de la Peña, M.; Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Rojas-Graü, M.A.; Martín-Belloso, O. Impact of high intensity pulsed electric field on antioxidant properties and quality parameters of a fruit juice-soymilk beverage in chilled storage. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 43, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, E.; Phull, S.S.; Lorimer, J.P.; Mason, T.J. The development and evaluation of ultrasound for the treatment of bacterial suspensions. A study of frequency, power and sonication time on cultured Bacillus species. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003, 10, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyasena, P.; Mohareb, E.; McKellar, R.C. Inactivation of microbes using ultrasound: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 87, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Murakami, M.; Kawai, Y.; Inoue, N.; Matsuda, T. Use of nisin for inhibition of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in acidic drinks. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, I.E.; Mastwijk, H.C.; Bartels, P.V.; Smid, E.J. Pulsed-electric field treatment enhances the bactericidal action of nisin against Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleveland, J.; Montville, T.J.; Nes, I.F.; Chikindas, M.L. Bacteriocins: Safe, natural antimicrobials for food preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 71, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.I.V.; Griffiths, M.W.; Mittal, G.S.; Deeth, H.C. Combining non-thermal technologies to control foodborne microorganisms: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 89, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komitopolou, E.; Boziaris, I.S.; Davies, E.A.; Delves-Broughton, J.; Adams, M.R. Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in fruit juices and its control by nisin. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 34, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, W.E.; de Massaguer, P.R. Microbial modeling of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris CRA 7152 growth in orange juice with nisin added. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 1904–1912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Ciuffreda, E.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. Effects of lysozyme on Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris under laboratory conditions. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Inhibition of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores by natural compounds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Combining eugenol and cinnamaldehyde to control the growth of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris. Food Control 2010, 21, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, K.; Phillips, C. Potential antimicrobial uses of essential oils in food: Is citrus the answer? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settanni, L.; Palazzolo, E.; Guarrasi, V.; Aleo, A.; Mammina, C.; Moschetti, G.; Germanà, M.A. Inhibition of foodborne pathogen bacteria by essential oils extracted from citrus fruits cultivated in sicily. Food Control 2012, 26, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Campaniello, D.; Speranza, B.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. Control of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in apple juice by citrus extracts and a mild heat-treatment. Food Control 2013, 31, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Kokubo, R.; Sakaino, M. Antimicrobial activities of eucalyptus leaf extracts and flavonoids from Eucalyptus maculata. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 39, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontius, A.J.; Rushing, J.E.; Foegeding, P.M. Heat resistance of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris spores as affected by various pH values and organic acids. J. Food Prot. 1998, 61, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palop, A.; Lvarez, I.; Raso, J.; Condon, S. Heat resistance of Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius in water, various buffers, and orange juice. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciuffreda, E.; Bevilacqua, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. Alicyclobacillus spp.: New Insights on Ecology and Preserving Food Quality through New Approaches. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 625-640. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3040625

Ciuffreda E, Bevilacqua A, Sinigaglia M, Corbo MR. Alicyclobacillus spp.: New Insights on Ecology and Preserving Food Quality through New Approaches. Microorganisms. 2015; 3(4):625-640. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3040625

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiuffreda, Emanuela, Antonio Bevilacqua, Milena Sinigaglia, and Maria Rosaria Corbo. 2015. "Alicyclobacillus spp.: New Insights on Ecology and Preserving Food Quality through New Approaches" Microorganisms 3, no. 4: 625-640. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3040625

APA StyleCiuffreda, E., Bevilacqua, A., Sinigaglia, M., & Corbo, M. R. (2015). Alicyclobacillus spp.: New Insights on Ecology and Preserving Food Quality through New Approaches. Microorganisms, 3(4), 625-640. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms3040625