Distinct Neuropsychological Correlates of Apathy Sub-Domains in Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Neuropsychological Assessment

- i.

- global cognitive functioning by means of the Italian version of the MMSE [27], consisting of eleven questions tapping into temporal and spatial orientation, immediate and delayed verbal memory, language, attention, and praxis abilities, with a total score ranging from 0 to 30 according to the number of correct responses.

- ii.

- verbal memory by means of the immediate and delayed recall conditions of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT; [29]), consisting of a list of 15 words not semantically related to each other that participants are asked to remember both immediately, after the words are read for five times (learning recall), and, subsequently, after 20–30 min (delayed recall), with two total scores ranging from 0 to 75 for the learning recall, and from 0 to 15 for the delayed recall corresponding to the number of words correctly recalled;

- iii.

- visuospatial memory by means of the delayed recall of the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test, (ROCF, [30]), asking participants to draw from memory a previously presented complex figure composed of 18 elements, with the total correct score ranging from 0 to 36, according to the number of elements correctly drawn and placed (a score of 2 points may be awarded for each element);

- iv.

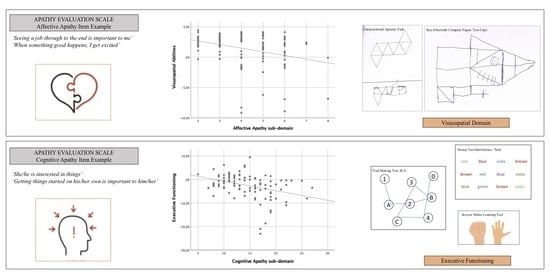

- visuospatial abilities by means of: the Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (RCPM; [29]), a non-verbal intelligence task tapping into logical reasoning on visuospatial material, with the total score ranging from 0 to 36 according to the number of matrices correctly completed; the Constructional Apraxia Task (CAT; [31]), tapping into construction skills by asking the participant to copy seven figures, with a total score ranging from 0 to 14 given by the number of figures correctly reproduced (a score of 2 points may be awarded for each figure); and the ROCF copy, asking participants to copy a complex figure, with the total score ranging from 0 to 36 given by the number of correctly reproduced elements;

- v.

- executive functioning by means of: the Clock Drawing Test (CDT; [32]), asking participants to place numbers on a printed circle as if depicting the face of a clock and then to draw the clock hands indicating a certain time (i.e., ten minutes past 11 o’clock), with the total score ranging from 0 to 10 given by the presence of the correct numbers and by the spatial accuracy of both the numbers and the hands; the Trail Making Test (TMT:B-A; [33]), consisting of two parts (A and B) asking participants to as quickly and accurately as possible connect a series of 25 circled and scattered numbers in ascending order (part A) and then to alternate numbers and letters in ascending/alphabetical order (1-A-2-B-3, etc.; part B), with the total score corresponding to the difference calculated in seconds taken by the participants to complete the part B and A of the task (part B-part A); Stroop test-interference task [34], tapping into the ability to inhibit cognitive interference by asking participants to name the color of the ink with which the color word is written (e.g., the word ‘violet’ printed with brown ink), with the total score given by the number of correct answers in 30 s; the Inverse Motor Learning Test (IML; [31]), tapping into the ability to inhibit imitation and perseveration by asking participants to inhibit a behavior shown by the examiner (e.g., every time the examiner raises his or her hand open, showing the palm, the participant must raise it closed, showing the fist, and vice versa) with the total score ranging from 0 to 24 given by the number of gestures correctly performed; the phonological verbal fluency task [29], tapping into lexical ability by asking participants to recall as many words as possible according to the initial letter (F, A, and S) within 1 min, with the total score given by the sum of the correctly retrieved words in all three conditions; and the semantic verbal fluency task [31], tapping into the participant’s ability to recall as many words as possible that belong to a certain semantic category (colors, animals, cities, and fruit), within 1 min, with the total score given by the average of the correctly re-enacted words for each category.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marin, R.S.; Biedrzycki, R.C.; Firinciogullari, S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991, 38, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Dubois, B. Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cereb. Cortex 2006, 16, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Starkstein, S.E.; Leentjens, A.F. The nosological position of apathy in clinical practice. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, P.; Onyike, C.U.; Leentjens, A.F.; Dujardin, K.; Aalten, P.; Starkstein, S.; Verhey, F.R.; Yessavage, J.; Clement, J.P.; Drapier, D.; et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niino, M.; Mifune, N.; Kohriyama, T.; Mori, M.; Ohashi, T.; Kawachi, I.; Shimizu, Y.; Fukaura, H.; Nakashima, I.; Kusunoki, S.; et al. Apathy/depression, but not subjective fatigue, is related with cognitive dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raimo, S.; Trojano, L.; Spitaleri, D.; Petretta, V.; Grossi, D.; Santangelo, G. Apathy in multiple sclerosis: A validation study of the apathy evaluation scale. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 347, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, A.M.; Batista, S.; Tenente, J.; Nunes, C.; Macário, C.; Sousa, L.; Gonçalves, F. Apathy in multiple sclerosis: Gender matters. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 33, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raimo, S.; Trojano, L.; Spitaleri, D.; Petretta, V.; Grossi, D.; Santangelo, G. The relationships between apathy and executive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology 2016, 30, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Olavarrieta, C.; Cummings, J.L.; Velazquez, J.; Garcia de la Cadena, C. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, S.; Spitaleri, D.; Trojano, L.; Santangelo, G. Apathy as a herald of cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis: A 2-year follow-up study. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, S.; Trojano, L.; Gaita, M.; d’Onofrio, F.; Spitaleri, D.; Santangelo, G. Relationship between apathy and cognitive dysfunctions in multiple sclerosis: A 4-year prospective longitudinal study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63, 103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santangelo, G.; Vitale, C.; Picillo, M.; Cuoco, S.; Moccia, M.; Pezzella, D.; Erro, R.; Longo, K.; Vicidomini, C.; Pellecchia, M.T.; et al. Apathy and striatal dopamine transporter levels in de-novo, untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dujardin, K.; Sockeel, P.; Delliaux, M.; Destée, A.; Defebvre, L. Apathy may herald cognitive decline and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimo, S.; Santangelo, G.; Trojano, L. The emotional disorders associated with multiple sclerosis. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 183, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, B.R.; Leigh, P.N.; Howard, R.J.; Barker, G.J.; Brown, R.G. Behavioural and emotional symptoms of apathy are associated with distinct patterns of brain atrophy in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 2481–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultzer, D.L.; Leskin, L.P.; Jacobs, Z.M.; Melrose, R.J.; Harwood, D.G.; Naarvaez, T.A.; Ando, T.K.; Mandelkern, M.A. Cognitive, behavioral, and emotional domains of apathy in Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical and neurobiological features. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, S144–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passingham, R.E.; Bengtsson, S.L.; Lau, H.C. Medial frontal cortex: From self-generated action to reflection on one’s own performance. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.S.S.; Vital, T.M.; Garuffi, M.; Stein, A.M.; Teixeira, C.V.L.; Costa, J.L.R.; Stella, F. Apathy, cognitive function and motor function in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2012, 6, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robert, P.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Agüera-Ortiz, L.; Aalten, P.; Bremond, F.; Defrancesco, M.; Hanon, C.; David, R.; Dubois, B.; Dujardin, K.; et al. Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 54, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.S.; Robert, P.; Ereshefsky, L.; Adler, L.; Bateman, D.; Cummings, J.; DeKosky, S.T.; Fischer, C.E.; Husain, M.; Ismail, Z.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for apathy in neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, 1892–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, R.; Turchetta, C.S.; Caruso, G.; Fadda, L.; Caltagirone, C.; Carlesimo, G.A. Neuropsychological correlates of cognitive, emotional-affective and auto-activation apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 2018, 118, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njomboro, P.; Deb, S. Distinct neuropsychological correlates of cognitive, behavioral, and affective apathy sub-domains in acquired brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; Banwell, B.; Clanet, M.; Cohen, J.A.; Filippi, M.; Fujihara, K.; Havrdova, E.; Hutchinson, M.; Kappos, L.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measso, G.; Cavarzeran, F.; Zappalà, G.; Lebowitz, B.D.; Crook, T.H.; Pirozzolo, F.J.; Amaducci, L.A.; Massari, D.; Grigoletto, F. The Mini-Mental State Examination: Normative study of an Italian random sample. Dev. Neuropsychol. 1993, 9, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carlesimo, G.A.; Caltagirone, C.; Gainotti, G. The Mental Deterioration Battery: Normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. The Group for the Standardization of the Mental Deterioration Battery. Eur. Neurol. 1996, 36, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffarra, P.; Vezzadini, G.; Dieci, F.; Zonato, F.; Venneri, A. Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: Normative values in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 2002, 22, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinnler, H.; Tognoni, G. Standardizzazione e taratura italiana di una batteria di test neuropsicologici [Italian standardization and classification of Neuropsychological tests]. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1987, 8, 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mondini, S.; Mapelli, D.; Vestri, A.; Bisiacchi, P. L’Esame Neuropsicologico Breve [Brief Neuropsychological Exam]; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milano, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giovagnoli, A.R.; Del Pesce, M.; Mascheroni, S.; Simoncelli, M.; Laiacona, M.; Capitani, E. Trail making test: Normative values from 287 normal adult controls. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1996, 17, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbarotto, R.; Laiacona, M.; Frosio, R.; Vecchio, M.; Farinato, A.; Capitani, E. A normative study on visual reaction times and two Stroop colour-word tests. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998, 19, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raimo, S.; Trojano, L.; Spitaleri, D.; Petretta, V.; Grossi, D.; Santangelo, G. Psychometric properties of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in multiple sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1973–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohner, V.; Brookes, R.L.; Hollocks, M.J.; Morris, R.G.; Markus, H.S. Apathy, but not depression, is associated with executive dysfunction in cerebral small vessel disease. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santangelo, G.; D’Iorio, A.; Maggi, G.; Cuoco, S.; Pellecchia, M.T.; Amboni, M.; Barone, P.; Vitale, C. Cognitive correlates of “pure apathy” in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 53, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, R.E.; Ott, B.R.; Grace, J.; Cahn-Weiner, D.A. Apathy and executive dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2003, 11, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa Salech, G.; Lillo, P.; van der Hiele, K.; Méndez-Orellana, C.; Ibáñez, A.; Slachevsky, A. Executive Function, and Emotion Recognition Are the Main Drivers of Functional Impairment in Behavioral Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia. Front. Neurol. 2022, 12, 734251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawagoe, T.; Onoda, K.; Yamaguchi, S. Apathy and Executive Function in Healthy Elderly-Resting State fMRI Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldman-Rakic, P.S. Circuitry of primate prefrontal cortex and regulation of behaviour by representational memory. In Handbook of Physiology; Plum, F., Mountcastle, U., Eds.; The American Physiological Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; pp. 373–417. [Google Scholar]

- Fuster, J.M. The Prefrontal Cortex; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, M.; Pandya, D.N. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: Comparative cytoarchitectonic analysis in the human and the macaque brain and corticocortical connection patterns. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 1011–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, Y.; Cronin-Golomb, A. Alexithymia and apathy in Parkinson’s disease: Neurocognitive correlates. Behav. Neurol. 2013, 27, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinlay, A.; Albicini, M.; Kavanagh, P.S. The effect of cognitive status and visuospatial performance on affective theory of mind in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2013, 9, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salamone, J.D.; Correa, M.; Yohn, S.; Lopez Cruz, L.; San Miguel, N.; Alatorre, L. The pharmacology of effort-related choice behavior: Dopamine, depression, and individual differences. Behav. Process. 2016, 127, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ippolito, M.; Spinelli, G.; Iosa, M.; Aglioti, S.M.; Formisano, R. The Possible Role of Apathy on Conflict Monitoring: Preliminary Findings of a Behavioral Study on Severe Acquired Brain Injury Patients Using Flanker Tasks. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admon, R.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Dysfunctional Reward Processing in Depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 4, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Domenico, S.I.; Ryan, R.M. The Emerging Neuroscience of Intrinsic Motivation: A New Frontier in Self-Determination Research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waliszewska-Prosół, M.; Nowakowska-Kotas, M.; Kotas, R.; Bańkowski, T.; Pokryszko-Dragan, A.; Podemski, R. The relationship between event-related potentials, stress perception and personality type in patients with multiple sclerosis without cognitive impairment: A pilot study. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 27, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Jiang, X.; Yue, F.; Wang, L.; Boecker, H.; Han, Y.; Jiang, J. Exploring dynamic functional connectivity alterations in the preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease: An exploratory study from SILCODE. J. Neural Eng. 2022, 19, 016036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletenik, I.; Alvarez, E.; Honce, J.M.; Valdez, B.; Vollmer, T.L.; Medina, L.D. Subjective cognitive concern in multiple sclerosis is associated with reduced thalamic and cortical gray matter volumes. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Demographic Variables | Mean ± SD | Range (Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.27 ± 11.1 | 21–68 |

| Education (years) | 12.47 ± 3.59 | 5–18 |

| Clinical variables | ||

| EDSS | 3.28 ± 1.53 | 1–6 |

| Duration of disease (months) | 114.93 ± 88.26 | 10–432 |

| Age at onset of disease (years) | 9.53 ± 7.24 | 1–36 |

| Global cognitive functioning | ||

| MMSE | 28.32 ± 1.99 | 20–30 |

| Behavioral Variables | ||

| AES | 33.97 ± 8.97 | 19–56 |

| AES-C | 14.51 ± 4.51 | 5–27 |

| AES-B | 9.30 ± 3.11 | 5–22 |

| AES-A | 4.17 ± 1.45 | 2–8 |

| HDRS | 8.68 ± 4.71 | 0–16 |

| Cognitive Variables | AES-C | AES-B | AES-A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | RAVLT immediate recall | −0.182 | −0.025 | −0.189 |

| RAVLT delayed recall | −0.157 | −0.076 | −0.179 | |

| ROCF delayed recall | −0.228 * | −0.009 | −0.229 * | |

| Praxis | Apraxia constructional task | −0.215 * | −0.019 | −0.181 |

| ROCF copy task | −0.311 ** | −0.103 | −0.248 * | |

| Executive Functions | Phonological verbal fluency task | −0.114 | −0.137 | −0.191 |

| Semantic verbal fluency task | −0.209 * | −0.094 | −0.240 * | |

| Stroop test-interference task | −0.529 ** | −0.238 * | −0.330 ** | |

| IML | −0.512 ** | −0.332 ** | −0.376 ** | |

| CDT | −0.254 * | −0.152 | −0.510 ** | |

| TMT: B-A | 0.237 * | 0.194 | 0.299 * | |

| Reasoning | RCMP | −0.269 * | −0.175 | −0.304 * |

| Behavioral Variable | ||||

| Depression | HDRS | 0.257 * | 0.303 * | 0.288 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raimo, S.; Gaita, M.; Costanzo, A.; Spitaleri, D.; Santangelo, G. Distinct Neuropsychological Correlates of Apathy Sub-Domains in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030385

Raimo S, Gaita M, Costanzo A, Spitaleri D, Santangelo G. Distinct Neuropsychological Correlates of Apathy Sub-Domains in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(3):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030385

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaimo, Simona, Mariachiara Gaita, Antonio Costanzo, Daniele Spitaleri, and Gabriella Santangelo. 2023. "Distinct Neuropsychological Correlates of Apathy Sub-Domains in Multiple Sclerosis" Brain Sciences 13, no. 3: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030385

APA StyleRaimo, S., Gaita, M., Costanzo, A., Spitaleri, D., & Santangelo, G. (2023). Distinct Neuropsychological Correlates of Apathy Sub-Domains in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Sciences, 13(3), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030385