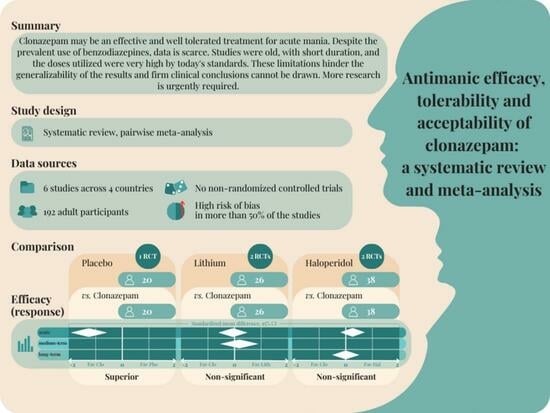

Antimanic Efficacy, Tolerability, and Acceptability of Clonazepam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Interventions and Types of Study Eligible for Inclusion

2.3. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.4. Outcome Measures and Data Extraction

- (i)

- Efficacy: response to treatment (continuous), measured as mean change scores (which were given preference) or endpoint scores (if data on change scores were not available), in symptoms of mania, using the Young Mania Rating Scale [35], any other validated rating scale, or authors’ definitions and measures of response, if the preferred data were not available.

- (ii)

- Tolerability (dichotomous): the proportion of participants who dropped out due to treatment emergent adverse effects (between the first treatment dose and endpoint).

- (iii)

- Acceptability (dichotomous): proportion of participants who dropped out due to any reason (all-cause discontinuation between the first treatment dose and endpoint).

- (i)

- Efficacy (dichotomous): response to treatment, defined as a reduction of ≥50% in the mean YMRS (Young Mania Rating Scale, which was given preference) [36] or any other similar validated rating scale, compared to baseline, or however defined by the authors if the above data were not available.

- (ii)

- Remission (dichotomous), measured as the proportion of patients in remission following treatment. Remission was defined as a YMRS score of ≤12 [36], equivalent on another validated scale, or however defined by the authors if the above data were not available.

- (iii)

- Efficacy: global state (continuous): change scores (which were given preference) or endpoint scores measured by the CGI (Clinical Global Impression) scale [37] (which was given preference) or any other similar validated rating scale.

- (iv)

- Efficacy: functioning (continuous): change score (preferable) or endpoint scores, measured by rating scales such as the Global Assessment of Functioning [38] or any other published rating scale.

- (v)

- Efficacy: psychotic symptoms (continuous): change scores (which were given preference) or endpoint scores measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale [39] or any other validated scale.

- (vi)

- Tolerability: specific adverse effects (continuous and/or dichotomous): proportion of participants experiencing specific treatment emergent adverse effects, change score or endpoint scores of any adverse effect rating scale. Examples of adverse effects include sedation, extrapyramidal side effects, and ataxia, among others.

- (vii)

- Use of antipsychotic medication as required: continuous (total antipsychotic dose utilized) and/or dichotomous (proportion of patients requiring rescue antipsychotic treatment in each group).

- (viii)

- Total dose of mood stabilizer in each group (continuous).

- (ix)

- Suicidality (dichotomous and/or continuous), as defined by the authors.

- (x)

- Quality of life (continuous), change score (preferable) or endpoint scores in any published rating scale (e.g., Quality of Life Scale [40]).

- (xi)

- Relapse in the course of follow-up (dichotomous), as defined by the authors.

- (xii)

- Insomnia (continuous): change score (preferable) or endpoint score of total nocturnal sleep time, defined as the total amount of time of sleep using subjective (for example, a sleep diary) or objective measures (for example, polysomnography).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Primary diagnosis or, if data were limited, distinguishing between mania with psychosis and mania without psychosis.

- Rapid cycling mania versus non-rapid cycling.

- Treatment-resistant mania versus non-treatment-resistant mania.

- Monotherapy versus add-on drug treatment.

- Distinct age groups: children and adolescents versus adults.

- Adults aged 65 and older versus those younger than 65.

- Presence of comorbid substance misuse versus no comorbidity.

- Any other variables relevant to investigating heterogeneity.

- Exclusion of studies that did not adhere to operationalized diagnostic criteria.

- Exclusion of non-randomized studies.

- Comparison of the fixed-effects model versus the random-effects model.

- Exclusion of studies with imputed data.

- Exclusion of sponsored studies.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Search

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4. Primary Outcomes

3.4.1. Efficacy: Response to Treatment

Clonazepam vs. Placebo

Clonazepam vs. Lorazepam

Clonazepam vs. Lithium

Clonazepam vs. Haloperidol

3.4.2. Tolerability (Discontinuation Due to Adverse Effects)

3.4.3. Acceptability (All Cause Discontinuation)

3.5. Secondary Outcomes

3.5.1. Response to Treatment (Dichotomous)

3.5.2. Remission (Dichotomous)

3.5.3. Efficacy—Global State

3.5.4. Efficacy—Functioning

3.5.5. Efficacy—Psychotic Symptoms

3.5.6. Total Antipsychotic Dose Utilized and/or Use of As-Required Antipsychotics during the Course of Treatment

3.5.7. Total Mood Stabilizer Dose Utilized/Plasma Levels in Case of Add-on Treatment

3.5.8. Tolerability—Specific Adverse Effects

3.5.9. Other Secondary Outcomes Mentioned in Our a Priori Written Protocol

3.6. Publication Bias

3.7. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses for the Primary Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Scarcity of Data

4.2. Other Limitations

4.2.1. Duration of the Included Trials

4.2.2. The Potential Effect of Old Studies and Studies from Mainland China

4.2.3. Concurrent Antipsychotic Prescribing in Trials Examining Clonazepam as a Monotherapy

4.2.4. Dose of Clonazepam Utilized

4.2.5. Discussion of the Outcomes of Tolerability and Acceptability, and Implications for Antimanic Mechanism of Action

4.3. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McIntyre, R.S.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Goldstein, B.I.; Lopez-Jaramillo, C.; Kessing, L.V.; Malhi, G.S.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Majeed, A.; et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet 2020, 396, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessing, L.V.; Vradi, E.; Andersen, P.K. Life expectancy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015, 17, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, T.M. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 131, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Yuan, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Akiskal, H.S.; Angst, J.; Greenberg, P.E.; Hirschfeld, R.M.; Petukhova, M.; Kessler, R.C. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, M.; Greene, M.; Guerin, A.; Touya, M.; Wu, E. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, P.B. Mania. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 57, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovsky, S.L. Mania. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2015, 21, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessing, L.V.; González-Pinto, A.; Fagiolini, A.; Bechdolf, A.; Reif, A.; Yildiz, A.; Etain, B.; Henry, C.; Severus, E.; Reininghaus, E.Z.; et al. DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria for bipolar disorder: Implications for the prevalence of bipolar disorder and validity of the diagnosis—A narrative review from the ECNP bipolar disorders network. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 47, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.J.; Lin, C.H.; Wu, H.C. Factors predicting re-hospitalization for inpatients with bipolar mania—A naturalistic cohort. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, A.C. Impulsivity in mania. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.E.; Malhi, G.S.; Cleary, M.; Lai, H.M.; Sitharthan, T. Comorbidity of bipolar and substance use disorders in national surveys of general populations, 1990–2015: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 206, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.L. Risk assessment and management in bipolar disorders. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 193, S21–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bipolar Disorder: Assessment and Management, Clinical Guideline [CG185]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/chapter/1-recommendations#managing-mania-or-hypomania-in-adults-in-secondary-care-2 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Patel, N.; Viguera, A.C.; Baldessarini, R.J. Mood-Stabilizing Anticonvulsants, Spina Bifida, and Folate Supplementation: Commentary. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 38, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, D.P.; Weiner, M.; Prabhakar, M.; Fiedorowicz, J.G. Mania and mortality: Why the excess cardiovascular risk in bipolar disorder? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2009, 11, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacchiarotti, I.; Anmella, G.; Colomer, L.; Vieta, E. How to treat mania. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 142, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetson, S.R.; Osser, D.N. Psychopharmacology of agitation in acute psychotic and manic episodes. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2022, 35, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovsky, S.L.; Marshall, D. Benzodiazepines Remain Important Therapeutic Options in Psychiatric Practice. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingard, L.; Taipale, H.; Reutfors, J.; Westerlund, A.; Boden, R.; Tiihonen, J.; Tanskanen, A.; Andersen, M. Initiation and long-term use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018, 20, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. In Use of Antipsychotics and/or Benzodiazepines as Rapid Tranquilization in In-Patients of Mental Facilities and Emergency Departments: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness and Guidelines; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Crescenzo, F.; D’Alò, G.L.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Ciabattini, M.; Di Franco, V.; Watanabe, N.; Kurtulmus, A.; Tomlinson, A.; Mitrova, Z.; Foti, F.; et al. Comparative effects of pharmacological interventions for the acute and long-term management of insomnia disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2022, 400, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, H.; Kahwaji, C.I. Clonazepam. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lechin, F. Effects of d-amphetamine, clonidine and clonazepam on distal colon motility in non-psychotic patients. Res. Commun. Psychol. Psychiatry Behav. 1982, 7, 385–410. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, W.J.; Goetz, C.; Nausleda, P.A.; Klawans, H.L. Clonazepam and dopamine-related stereotyped behavior. Life Sci. 1977, 21, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouinard, G. Antimanic effects of clonazepam. Psychosomatics 1985, 26, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouinard, G. The search for new off-label indications for antidepressant, antianxiety, antipsychotic and anticonvulsant drugs. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006, 31, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, G.S.; Weilburg, J.B.; Rosenbaum, J.F. Clonazepam vs. neuroleptics as adjuncts to lithium maintenance. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1990, 26, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, T.A.; Shukla, S.; Hirschowitz, J. Clonazepam treatment of five lithium-refractory patients with bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1989, 146, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, F.; Schulz, P. Clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania: A Bayesian meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 78, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feighner, J.P.; Robins, E.; Guze, S.B.; Woodruff, R.A., Jr.; Winokur, G.; Munoz, R. Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1972, 26, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Endicott, J.; Robins, E. Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1978, 35, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.C.; Biggs, J.T.; Ziegler, V.E.; Meyer, D.A. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, W.; Durgam, S.; Lu, K.; Ruth, A.; Németh, G.; Laszlovszky, I.; Yatham, L.N. Clinically relevant response and remission outcomes in cariprazine-treated patients with bipolar I disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busner, J.; Targum, S.D. The clinical global impressions scale: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aas, I.H. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF): Properties and frontier of current knowledge. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall, J.E.; Hollister, L.E.; Pichot, P. Major psychiatric disorders. A four-dimensional model. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1967, 16, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C.S.; Anderson, K.L. The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): Reliability, validity, and utilization. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani, A.; Barbui, C.; Salanti, G.; Rendell, J.; Brown, R.; Stockton, S.; Purgato, M.; Spineli, L.M.; Goodwin, G.M.; Geddes, J.R. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2011, 378, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, G.; Young, S.N.; Annable, L. Antimanic effect of clonazepam. Biol. Psychiatry 1983, 18, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouinard, G.; Annable, L.; Turnier, L.; Holobow, N.; Szkrumelak, N. A double-blind randomized clinical trial of rapid tranquilization with I.M. clonazepam and I.M. haloperidol in agitated psychotic patients with manic symptoms. Can. J. Psychiatry Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 1993, 38 (Suppl. S4), S114–S121. [Google Scholar]

- Bradwejn, J.; Shriqui, C.; Koszycki, D.; Meterissian, G. Double-blind comparison of the effects of clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1990, 10, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.; Stephenson, U.; Flewett, T. Clonazepam in acute mania: A double blind trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1991, 25, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H.M.; Berk, M.; Brook, S. A randomized controlled single blind study of the efficacy of clonazepam and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 1997, 12, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.D.; Li, J.; Tan, Y.L.; Chen, D.C.; Yao, F.X.; Zhang, X.L.; Li, S.M.; Ji, C.J.; Huang, W.S.; Zhang, G.H.; et al. Optimized therapeutic scheme and individualized dosage of sodium valproate in patients with bipolar disorder sub-type I. Chin. J. New Drugs 2009, 18, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikalinos, T.A.; Churchill, R.; Ferri, M.; Leucht, S.; Tuunainen, A.; Wahlbeck, K.; Ioannidis, J.P. Effect sizes in cumulative meta-analyses of mental health randomized trials evolved over time. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2004, 57, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Tanious, M.; Das, P.; Berk, M. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2012, 46, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; Leucht, C.; Huhn, M.; Chaimani, A.; Mavridis, D.; Helfer, B.; Samara, M.; Rabaioli, M.; Bächer, S.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Sixty Years of Placebo-Controlled Antipsychotic Drug Trials in Acute Schizophrenia: Systematic Review, Bayesian Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of Efficacy Predictors. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yin, P.; Freemantle, N.; Jordan, R.; Zhong, N.; Cheng, K.K. An assessment of the quality of randomised controlled trials conducted in China. Trials 2008, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Du, L.; Liu, G.; Fu, J.; He, X.; Yu, J.; Shang, L. Quality assessment of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding in traditional Chinese medicine RCTs: A review of 3159 RCTs identified from 260 systematic reviews. Trials 2011, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhead, M. 80% of China’s clinical trial data are fraudulent, investigation finds. BMJ 2016, 355, i5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloos, J.M.; Lim Cow, C.Y.S.; Bocquet, V. Benzodiazepine high-doses: The need for an accurate definition. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 30, e1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary 85. Available online: https://www.medicinescomplete.com/#/browse/bnf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Bergman, H.; Bhoopathi, P.S.; Soares-Weiser, K. Benzodiazepines for antipsychotic-induced tardive dyskinesia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 1, Cd000205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujalte, D.; Bottaï, T.; Huë, B.; Alric, R.; Pouget, R.; Blayac, J.P.; Petit, P. A double-blind comparison of clonazepam and placebo in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 1994, 17, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author and Year of Publication | Study Location | Design | Duration | Diagnostic Criteria | Baseline Severity of Illness | Information about Participants’ Age (Years) | Setting | Arms and Number of Participants per Arm | Information about Clonazepam Preparation and Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edwards 1991 [48] | New Zealand | Double-blind, parallel RCT | 5 days | DSM-III | Mean CGR-mania = 4.75 (1.19) | Mean age per group *: 34.2 and 31.7 | Inpatient | Clonazepam (N = 20) vs. placebo (N = 20), monotherapy, as required antipsychotic allowed. | Oral, 6 mg daily, fixed dose |

| Bradwejn 1990 [47] | Canada | Double-blind, parallel RCT | 1st Phase: 14 days. 2nd Phase: 28 days | DSM-III | Mean CGI per group: 5 and 5.2 * | Mean age/SD: 41.68 (11.93) | Inpatient | 1st Phase: Clonazepam (N = 11) vs. Lorazepam (N = 13), monotherapy 2nd Phase: Clonazepam + Lithium vs. Lorazepam + Lithium, allowed as required antipsychotic | Oral, mean = 14.2 (6.7) mg daily (range: 6–20 mg daily) |

| Chouinard 1983 [45] | Canada | Double-blind, cross-over RCT | 10 days | Spitzer 1978 | Mean CGI-mania = 8.2 (0.6) | Median = 43 * | Inpatient | Clonazepam vs. Lithium (N = 12), monotherapy, but as required antipsychotic allowed | Oral, mean = 10.4 (6.7) mg daily (range 4–16 mg daily) |

| Clark 1997 [49] | South Africa | Open (unblinding due to design limitations) parallel RCT | 28 days | DSM-IV | Mean CGI = 4.63 (0.624) | 18–65 * | Inpatient | Clonazepam (N = 15) vs. Lithium (N = 15), monotherapy, but as required antipsychotics allowed. | Oral, range: 8–16 mg * |

| Chouinard 1993 [46] | Canada | Double-blind parallel RCT | 1 day (2 h) | DSM-III | Mean CGI = 5.45 (1.15) | 34.95 (10.01) | Inpatient | Clonazepam (N = 8) vs. Haloperidol (N = 8), 75% of patients on regular antipsychotics | Intramuscular injection, mean = 5.4 (1.2)mg |

| Yang 2009 [50] | China | Single-blind, parallel RCT | 16 weeks | DSM-IV | Mean CGI = 5.25 (0.45) | Mean = 31.85 (10.27) | Inpatient | Clonazepam + Valproate (N = 30) vs. Haloperidol + Valproate (n = 30), as required antipsychotics not allowed, but as required benzodiazepines and hypnotics allowed. | Oral, range: 2–6 mg daily * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lappas, A.S.; Helfer, B.; Henke-Ciążyńska, K.; Samara, M.T.; Christodoulou, N. Antimanic Efficacy, Tolerability, and Acceptability of Clonazepam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12185801

Lappas AS, Helfer B, Henke-Ciążyńska K, Samara MT, Christodoulou N. Antimanic Efficacy, Tolerability, and Acceptability of Clonazepam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(18):5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12185801

Chicago/Turabian StyleLappas, Andreas S., Bartosz Helfer, Katarzyna Henke-Ciążyńska, Myrto T. Samara, and Nikos Christodoulou. 2023. "Antimanic Efficacy, Tolerability, and Acceptability of Clonazepam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 18: 5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12185801

APA StyleLappas, A. S., Helfer, B., Henke-Ciążyńska, K., Samara, M. T., & Christodoulou, N. (2023). Antimanic Efficacy, Tolerability, and Acceptability of Clonazepam: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(18), 5801. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12185801