1. Introduction

As waves propagate into shallow water, they change from almost sinusoidal in deep water to a sawtooth like shape in the surf zone. Troughs become wide and shallow; crests peak and lean forward, eventually overturning and breaking. In the spectral domain, this evolution is expressed in energy transfers from the spectral peak to peak harmonics and low frequency (between 0.001 Hz and 0.02 Hz) waves, as well as the development of phase correlations across the spectrum. Wave-shape evolution and the generation of zero-frequency motions (mean flow, wave setup) have significant effects on nearshore sediment transport and inundation.

Modeling nonlinear shoaling is challenging. Off-the-shelf finite-depth spectral models (e.g., SWAN [

1]) are typically based on variance balance equations originally developed for deep-water waves [

2], and therefore cannot account for phase correlation effects. Describing directional nonlinear wave interactions is problematic in intermediate depth. Shallow water spectra are typically wide (containing harmonics and low frequency waves) precluding the use of simpler weak dispersion approximations (cubic Schrodinger equation e.g., [

3,

4,

5,

6] or Boussinesq approximations, e.g., [

7,

8,

9,

10]).

The fundamental challenge of modeling nonlinear shoaling in the spectral domain resides in the character of wave interactions. The basis of the spectral representation is the decomposition of the wave field into statistically independent (in the leading order) Fourier modes. For a flat bottom (water depth

h = constant), this representation is formally

where

η is the free surface displacement,

a is the complex modal amplitude,

ω is the radian frequency, and “

c.c.” stands for “complex conjugate”. The sum (used here to denote symbolically any type of superposition, either discrete or continuous) is carried out over frequencies (indexed by

n). Different directions of propagation are represented here by the wave number vector

Kn,m which depends on both the frequency index and an additional index

m, specifying, say, the propagation angle. For a given

ωn and a given depth

h, Equation (1) constrains the modulus of the wave number vector of modulus

Kn. The efficiency of wave nonlinearities [

3,

11] depends on the system of equations describing the resonance state of

N interacting modes.

Note that Equation (3) is a system of two equations for the components of the horizontal wave number vector. With the additional constraint (Equation (2)), only two of the three scalar equations (Equations (2) and (3)) can be independent. A set of

N modes that satisfy Equations (2) and (3) is said to interact resonantly; those that do not are called non-resonant. In the wave evolution equation, the efficiency of resonant

N-wave interactions scales like

O(εN−1), where

ε is the characteristic wave slope. Non-resonant effects are weaker and dynamically less relevant (produce higher order bound waves). Due to the form of the dispersion relation (Equation (1)), the smallest number of modes that can be resonant is

N = 4 (quadruplet, or four-wave interaction); triad interactions (

N = 3) are non-resonant in any water depth [

12]; however, they approach resonance in shallow water.

The statistics of wave evolution can be described in terms of competing effects of dispersion and nonlinearity [

13,

14]: nonlinearity builds phase correlations and skews the statistical distribution of the wave-field; dispersion breaks them and restores the symmetry of the distribution.

In deep water, the dispersive terms of the evolution equation are of order

ε, while the competing leading-order nonlinearity (resonant four-wave interactions) is of order

ε3. Consequently, the wave field is Gaussian in the leading order, with its statistics completely determined by second order moments (variance, power spectrum; [

2,

15]), hence the suitability of models based on energy-balance equations.

As water becomes shallow, dispersion weakens to order

ε2 while nonlinearity strengthens. Near-resonant triad interaction (order

ε2) becomes the leading order nonlinear mechanism (e.g., [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] and many others). The evolution is characterized by the broadening of the spectrum, and the generation of significant phase correlations across the spectrum (wave crests peak, wave fronts steepen). The waves are no longer Gaussian: wave statistics are no longer completely determined by second order moments (power spectrum) alone, and higher order moments and spectra (e.g., bispectra) become important. Evolution depends on both local sea state and wave history (history of phase correlations).

The dynamics of triad interaction in shallow water are poorly (or not at all) implemented in existing numerical models. For example, SWAN [

1] arguably the most advanced coastal spectral model, is essentially built on a WAM [

15] energy balance structure [

2]. It implements a crude and unrealistic triad interaction parameterization [

21], limited to approximating collinear second harmonic generation exclusively, with depth dependent interaction coefficients alone (

i.e., accounting only for local effects, and not for wave history). Important processes such as infragravity (IG) wave generation, recurrence effects, and spectrum widening are also ignored.

A deterministic, unidirectional but complete triad interaction formulation was first introduced by [

16] based on the Boussinesq approximation. Agnon

et al. [

20] proposed a generalization for arbitrary depth based on the Nonlinear Mild Slope Equation (NMSE, [

22,

23]). Limited directionality can be introduced using the parabolic approximation (e.g., [

24,

25,

26]). Hyperbolic forms for nearly planar beaches were developed by [

20,

27,

28].

This paper describes the modeling techniques used to implement the hyperbolic form of the NMSE developed by [

20,

29] for directional three-wave interaction. Development of the model is presented first followed by a demonstration of the model’s capabilities for shore-perpendicular and oblique wave propagation. Finally, a summary of the work is presented along with a discussion of future enhancements to the model.

2. Model Development

2.1. Nearshore Directional Waves

In Equation (1), the directionality of mode n is expressed by the direction of the wave number K. The wave number vector is an invariant of propagation in deep water, and can be used to label directional modes. The wave number is considered an independent variable, with ω given by Equation (1), and modes are identified by the wave number components or, in polar coordinates, by the pair (K,θ), where θ is the angle of propagation. Thus, directional modes are represented by a two-dimensional parameter space (e.g., indices n and m in Equation (1)).

In the nearshore,

K is no longer invariant, but the wave frequency typically is. If the beach has straight and parallel isobaths, the alongshore wave number provides a second invariant that can be used to complete the two degrees of freedom necessary for describing directional waves. Therefore, in the nearshore, the Fourier representation of Equation (1) can be replaced by

where

x and

y are the cross- and alongshore coordinates. The independent parameters are, in the approach, the frequency

fn (or

ωn = 2

πfn), and the alongshore wave number

κm. The wave number modulus

K depends on the frequency through Equation (1), and the cross-shore wave number

k is a function of both

f and

κ through Equation (5). A mode is therefore defined as the pair

(fn,κm)—indexing modes rather than the independent parameters—and mode

J is defined as the pair

From Equation (6), for a given frequency

f, and at a given cross-shore location

x, progressive modes satisfy the condition

where

K(f,κ) is the local wavenumber modulus, given by the linear dispersion relation, Equation (1). Modes that do not satisfy this relation in some nearshore domain are called trapped modes. The location

x0 at which

k =

K(f,x0) is called the “turning point”. For simple (e.g., monotonic) beach profiles, shoreward of the turning point, trapped modes can acquire oscillatory behavior since

K→∞ as

h→0.

2.2. A Hyperbolic Nonlinear Mild Slope Equation (NMSE)

The numerical model described here implements the formulation proposed by [

27] (see also [

20]) for the nonlinear evolution of directional waves over a mildly sloping beach. The stationary nonlinear mild-slope equation can be written as

where

J,

P, and

Q are directional Fourier modes in the sense of Equation (6), and

cj is the cross-shore component of the model group velocity

C. The parameter

dj represents dissipation and/or growth processes, such as breaking, wind input, bottom friction, and others. In Equation (8),

δ is the Kronecker symbol, for example,

where the equality

J =

P has the regular meaning for ordered pairs,

i.e.,

fJ =

fP and

κJ =

κP. Only modes that satisfy the selection criteria given by Equation (10) are allowed to contribute to the nonlinear terms. Triads satisfying

J =

P +

Q (“sum” interaction) are responsible for transferring energy toward high frequencies; difference interactions

J = −

P +

Q transfer energy toward low frequencies. An example of a sum-interaction triad is shown in

Figure 1. With the notation,

![Jmse 02 00140 i017]()

, the interaction coefficient is

Figure 1.

An example of a sum-interaction triad J(j,s) = Q(q,v) + P(p,u), j = q + p and s = v + u with j = 3, q = 1, p = 2 and s = 4, v = 3, u = 1.

Figure 1.

An example of a sum-interaction triad J(j,s) = Q(q,v) + P(p,u), j = q + p and s = v + u with j = 3, q = 1, p = 2 and s = 4, v = 3, u = 1.

Equation (8) represents the Nonlinear Mild Slope Equation (NMSE) model. The NMSE is hyperbolic and describes wave shoaling, refraction, and three-wave nonlinear interactions. The unknown function BJ is related to the energy flux in the cross-shore direction, |BJ|2 = |aJ|2cJ. The linear part of the equation describes the conservation of the cross-shore component of the modal energy flux (the alongshore component is conserved trivially). The quadratic term represents the contribution of three-wave interaction to mode evolution and redistributes energy flux between modes.

The numerical implementation of Equation (8) is restricted only to triads that are close enough to resonance, as measured by the “detuning” parameter

The parameter

μ compares the wavelength of the nonlinear term with the wavelength of mode

J (on the left-hand side of the equation). If

μ >> 1, the oscillations of the nonlinear term are fast and result in a small (second-order) “bound wave” correction to mode

J that can be calculated approximately as

This approximation becomes singular as μ→0. This occurs as h→0, i.e., triads approach resonance as the water becomes shallow. In this case, the oscillation of the nonlinear term is slow and the equation has to be integrated numerically. In principle, the numerical solver should be able to handle triads with arbitrary values of μ. In practice, however, numerical calculations for μ = O(1) are slow because the model has to resolve fast oscillations that yield small contributions to the derivative. Controlling the errors becomes increasingly difficult for larger values of μ and the benefit of the effort becomes negligible. Because of that, an efficient numerical implementation of Equation (8) would limit the integration to triads characterized by μ < μc, for some critical value of μc, with bound waves computed using Equation (13). The numerical simulations shown here use μc = 0.5, while the bound waves are ignored (will be included in future modifications of the code).

Equation (8) is valid strictly for progressive waves. Trapped modes are not allowed to interact in the spatial domain where their cross-shore structure is exponential, but are allowed in the domain where they have oscillatory behavior. The NMSE model is phase resolving, in that it requires initial values for both modal amplitudes and modal phases.

Equation (8) reduces to the unidirectional equation for a mild sloping beach [

16,

20,

25] if all the modes propagate perpendicular to the shoreline,

i.e., for all

κJ = 0. Numerical simulations using the unidirectional hyperbolic NMSE [

27,

29] have been extensively verified against both single-triad analytic solutions as well as laboratory and field observations.

In the current implementation of the model, the only dissipation mechanism used is depth-limited wave breaking, based on the frequency dependent parameterization developed by [

29,

30], with dissipation uniformly distributed over all directions.

2.3. Model Discretization and Computational Grid

In Fourier series representation, the frequency-alongshore wave number is discretized as

and a directional mode index

J is a pair of indices

J =

(j,s). For a triad of interacting modes

J,

P, and

Q, the selection criterion given in Equation (10) can be written as indicial equations

where

for a given

f, the effective

κ-range of the allowable modes is limited by Equation (7), and can vary with depth. As the maximum extents of

f and κ are known, a list of all possible triads can be created before shoreward marching of the solver begins. The matrix of triads involving a given mode

J (in the left-hand side of Equation (8)) and all the allowable modes

P and

Q (right-hand side of Equation (8)) is

Because the selection criteria (Equation (10)) are invariants of propagation, the interacting triads can be pre-computed for a given

(f,κ) matrix.

2.4. Solution Algorithm

The NMSE represents a coupled system of

N × (2

M + 1) complex ODEs, a hyperbolic initial value problem. These equations are solved using the Vode ODE Solver [

31] using a non-stiff Adams method. Although the NMSE is written in complex form, for purposes of solving, the equation is split into real and imaginary components (doubling the number of equations to solve simultaneously) thus enabling the double precision (8 byte) real version of Vode to be used. An overview of the solution algorithm is shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Solution algorithm.

Figure 2.

Solution algorithm.

As waves propagate into shallower water, trapped modes (modes for which

k =

K at some depth) become active and participate in the interaction. A trapped mode is considered inactive (

i.e., not allowed to interact with other modes) in the domain where

k >

K, but becomes active if

k <

K (

i.e., shoreward of the turning point for monotonic beach profiles). Triads containing inactive modes are disabled; therefore, the maximum effective alongshore wave number (

κmax =

M ∆κ) depends on the local (cross-shore position) depth and frequency. The conditions that determine

M are

where

K is determined by the dispersion relation (Equation (1)) and

![Jmse 02 00140 i018]()

refers to the integer value.

The maximum effective wave number increases with frequency and decreasing depth. The variation of

M with depth and frequency can be handled using two different strategies: (1) Using the minimum depth and highest frequency, the maximum

M for the entire domain can be determined; (2) Increase

M as the solution marches toward the shore. The current implementation of the model uses Approach 1. This approach will result in sparse matrices (wasting some computer memory) but the triad interaction patterns can be defined once for all runs and there is no need to dynamically modify

M as the solution marches toward the shore. For each evaluation of the derivatives, it is only necessary to determine whether all modes of the triad are active. Approach 2 is expected to result in dense matrices but also to significantly complicate coding as array sizes would vary as a function of cross-shore position. As with Approach 1, it is still necessary to determine whether all modes of the triad are active. A pseudocode representation of how the model calculates the right hand side of the NMSE (Equation (8)) is shown in the

Appendix.

3. Nonlinear Shoaling of Two JONSWAP Spectra: Shore-Perpendicular and Oblique Propagation

We demonstrate the capabilities of the model with two shoaling tests over a plane beach of 0.03 slope. The offshore spectra are standard directional JONSWAP spectra propagating shore-perpendicular in the first test, and obliquely in the second. The parameters used here (

Table 1) are typical for long Eastern Pacific swells; however, the directional spread is probably exaggerated in the simulations. The JONSWAP spectral shape (maybe not entirely realistic for representing the incoming waves at the deep end of the simulation domain) is used here solely to illustrate the capabilities of the current model and the use of the RPA for simulating the shoaling transformation of a deep-water variance density distribution. Because the JONSWAP spectrum does not contain any variance in the infragravity band, the second-order bound spectrum associated with the deep water swell was computed using Equation (13). A summary of the simulation parameters for both scenarios is shown in

Table 1.

Figure 4.

Directional characteristics of the frequency-alongshore wave number (f,κ) representation in comparison with the standard (deep-water) frequency-angle (f,θ) representation, in 15 m water depth (upper panels) and in 3 m water depth (lower panels). (a,c) The (f,κ) representation; contours show the corresponding angles of propagation with respect to shore-parallel. The shaded area in (a) marks trapped-wave modes (i.e., modes that have the turning point between 15 m and 3 m water depth). The nodes of the (f,κ) grid are marked by blue points.

Figure 4.

Directional characteristics of the frequency-alongshore wave number (f,κ) representation in comparison with the standard (deep-water) frequency-angle (f,θ) representation, in 15 m water depth (upper panels) and in 3 m water depth (lower panels). (a,c) The (f,κ) representation; contours show the corresponding angles of propagation with respect to shore-parallel. The shaded area in (a) marks trapped-wave modes (i.e., modes that have the turning point between 15 m and 3 m water depth). The nodes of the (f,κ) grid are marked by blue points.

For input-output purposes, the numerical model requires mapping the directional wave information between the model

(f,κ) grid and the standard frequency-angle representation

(f,θ) (e.g., as used in WAVEWATCH III™ [

35]). The existence of turning points makes the implementation of the mapping procedure sensitive to the bathymetric profile. For a given frequency, turning points (

Section 2.1) are cross-shore locations where additional modes are introduced into the system (become active). Their effect on the geometry of the computational grid is illustrated in

Figure 4. The active computational grid is limited to the band defined by

|κ| <

K(f,h), where

K(f,h) is given by Equation (1). In deep water, this is a narrow band (widening toward higher frequencies,

Figure 4a). As the water depth decreases, the band widens (additional modes become active), and becomes triangular in shape (

Figure 4c) and extends into higher alongshore wave numbers as the shallow water boundary approaches

|κ| <

Kshallow =

ω(gh)−1/2. As the limiting alongshore wave number increases, the frequency-angle representation degrades slightly (in

Figure 4d, the mapped grid does not cover the entire available

(f,θ) domain).

Designing the computational grid for applications poses thus the additional challenge of balancing the conflicting needs for resolving wide propagation angles (large limiting κ) at high resolution (small κ increments), and for keeping the number of triads described reasonably small for numerical integrations. The need for wide angles is non-trivial: for example, it is straightforward to check that directional difference triads containing two nearly collinear, shore-normal swell modes can excite a low-frequency wave that propagates nearly parallel to the shoreline. Note also that a significant fraction of the computational grid is never used.

Mapping the directional spectral distribution between

(f,κ) and

(f,θ) space

s, shown in

Figure 5, consists of two steps in each direction: a direct mapping of the modal amplitudes from the uniform grid (or angle,

Figure 5a or alongshore wave number,

Figure 5c) onto a non-uniform one in the complementary space (

Figure 5b or

Figure 5d), and a re-sampling (interpolation) of the non-uniformly spaced values into the uniform grid. All transformations are designed to preserve the frequency spectrum (

i.e., the directional spectrum integrated over either angles or wave number).

Figure 5.

Illustration of the mapping of the directional JONSWAP spectrum from the (f,θ) space onto the (f,κ) space, and back for the shore-perpendicular spectrum. Upper panels: directional spectra in different representations; lower panels: corresponding frequency spectrum. The transformation preserves the frequency spectrum. (a) Standard (f,θ) representation of the JONSWAP directional spectrum at 15 m isobaths; (b) Direct map from (f,θ) to (f,κ). The resulting grid in κ is not uniform; (c) Spectrum re-sampled in the uniform κ grid used for computation; (d) Spectrum directly mapped back to (f,θ) space. The angle grid is not uniform. Units of the variance density contour plots are arbitrary.

Figure 5.

Illustration of the mapping of the directional JONSWAP spectrum from the (f,θ) space onto the (f,κ) space, and back for the shore-perpendicular spectrum. Upper panels: directional spectra in different representations; lower panels: corresponding frequency spectrum. The transformation preserves the frequency spectrum. (a) Standard (f,θ) representation of the JONSWAP directional spectrum at 15 m isobaths; (b) Direct map from (f,θ) to (f,κ). The resulting grid in κ is not uniform; (c) Spectrum re-sampled in the uniform κ grid used for computation; (d) Spectrum directly mapped back to (f,θ) space. The angle grid is not uniform. Units of the variance density contour plots are arbitrary.

The evolution of a total of

N × (2

M + 1) = 100 × 61 = 6100 possible (however, some high-frequency trapped modes never become active) directional modes are simulated (

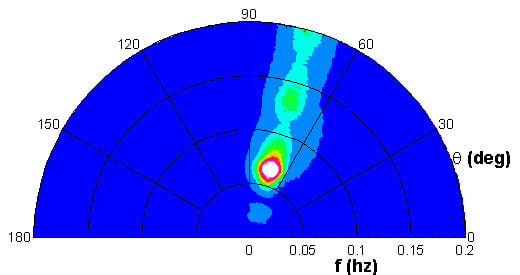

Figure 4). For each scenario, simulations are performed with both the full, and the linearized version of Equation (8). Note that the present implementation of the model only includes the linear and triad nonlinear evolution “engine” and wave breaking, with no additional physics (e.g., wave setup), that would be essential for realistic modeling of wave propagation in the nearshore.

The simulations shown here test the representation capability of the

(f,κ) grid as well as illustrate the directional effects of nonlinear shoaling. The initial spectra at the deep-water end of the domain (15 m water depth) are shown in

Figure 6a and

Figure 7a. Linear runs (

Figure 6b and

Figure 7b) show the expected refraction effect of decreasing directional spread, with modes slowly turning around toward shore-perpendicular propagation. The main nonlinear effects (clearly visible in

Figure 6c and

Figure 7c) are energy transfers from the peak to (a) peak harmonics, and (b) low-frequency infragravity modes. For oblique propagation, artifacts of the resolution of the

k-grid are visible in the deep-water spectrum (

Figure 7a), but become less severe as the waves refract and the grid coverage in the frequency-angle space increases with decreasing water depth. Note that infragravity waves (frequency < 0.05 Hz) are significantly more directionally spread (approximately 60 degrees) than the rest of the spectrum (approximately 30 degrees for swell and 15 degrees for the shortest waves represented).

Figure 6.

Evolution of the directional shore-perpendicular JONSWAP spectrum (see

Table 1). (

a) Initial spectrum in 15 m water depth; (

b) Linear evolution (3 m water depth); (

c) Nonlinear evolution (3 m water depth). Simulations are averages over

N = 100 random phase realizations.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the directional shore-perpendicular JONSWAP spectrum (see

Table 1). (

a) Initial spectrum in 15 m water depth; (

b) Linear evolution (3 m water depth); (

c) Nonlinear evolution (3 m water depth). Simulations are averages over

N = 100 random phase realizations.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the directional oblique JONSWAP spectrum (see

Table 1). (

a) Initial spectrum in 15 m water depth; (

b) Linear evolution (3 m water depth); (

c) Nonlinear evolution (3 m water depth). Simulations are averages over

N = 100 random phase realizations.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the directional oblique JONSWAP spectrum (see

Table 1). (

a) Initial spectrum in 15 m water depth; (

b) Linear evolution (3 m water depth); (

c) Nonlinear evolution (3 m water depth). Simulations are averages over

N = 100 random phase realizations.

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the free surface elevation corresponding to one of the realizations used to estimate the spectra in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The figures illustrate the change in the wave shape caused by the excitation of the phase-correlated harmonics of the spectral peak. A comparison of the linear (

Figure 8a) and nonlinear (

Figure 8b) oblique wave field clearly shows the steepening of the wave front. Both the shore-perpendicular and the oblique propagation realizations generate a significant infragravity field, with heights between 0.2 and 0.4 m. This effect is mainly a nonlinear shoaling effect (the linear shoaling of the initial bound infragravity band accounts for about 5 cm of the heights).

Figure 8.

Contours of the simulated free surface elevation field for shore-perpendicular propagation, corresponding to the spectrum shown in

Figure 6 at a fixed (arbitrary) time. The parameters of the offshore spectrum are given in

Table 1. (

a) Linear model; (

b) Nonlinear model; (

c) Infragravity waves (

f < 0.05 Hz) generated during nonlinear shoaling.

Figure 8.

Contours of the simulated free surface elevation field for shore-perpendicular propagation, corresponding to the spectrum shown in

Figure 6 at a fixed (arbitrary) time. The parameters of the offshore spectrum are given in

Table 1. (

a) Linear model; (

b) Nonlinear model; (

c) Infragravity waves (

f < 0.05 Hz) generated during nonlinear shoaling.

Figure 9.

Contours of the simulated free surface elevation field for oblique propagation, corresponding to the spectrum shown in

Figure 7 at a fixed (arbitrary) time. The parameters of the offshore spectrum are given in

Table 1. (

a) Linear model; (

b) Nonlinear model; (

c) Infragravity waves (

f < 0.05 Hz) generated during nonlinear shoaling.

Figure 9.

Contours of the simulated free surface elevation field for oblique propagation, corresponding to the spectrum shown in

Figure 7 at a fixed (arbitrary) time. The parameters of the offshore spectrum are given in

Table 1. (

a) Linear model; (

b) Nonlinear model; (

c) Infragravity waves (

f < 0.05 Hz) generated during nonlinear shoaling.

4. Summary and Conclusions

Based on the equations derived in [

27], a Fortran 95/2003 code was written to solve the NMSE. The model (as of Version 1-38) contains approximately 32,000 lines of code, 60% of which is the Vode ODE solver and 8% are testing routines. The model has been compiled using several different Fortran compilers (GNU 4.8 and Intel 2013) and executed under several different LINUX platforms (Ubuntu and RHEL). This implementation of the NMSE is a phase-resolving, spectral

(f,k) model that describes wave evolution over a beach with straight and parallel isobaths. The model solves set of hyperbolic equations for a two-dimensional surface gravity wave field approaching a beach accounting for non-linear, quadratic triad interactions, shoaling and refraction. The capabilities of the model are illustrated for shore-perpendicular and oblique propagation of a directional JONSWAP spectrum. The results show wide-angle infragravity (IG) generation as well as significant energy transfers toward high-frequencies modes. The runs demonstrate the essential role directionality plays in nonlinear shoaling, especially in the generation of directionally spread infragravity waves.

With the “engine” of a wave model developed, future research goals include: (1) Reformulating the governing equation from its current mathematically relevant form to one which is more numerically adept. By solving an equation better suited to floating point arithmetic (e.g., a form which minimizes rounding error), we should be able to improve the model’s stability, accuracy and energy flux conservation; (2) Adding modules for relevant physics such as setup (feedback to the total depth) and wind effects; (3) Performing additional numerical tests. Comparing the model to known analytic solutions (e.g., individual triad interactions) as well as observational directional wave data will provide for better model verification and validation. Additional IG scenarios will let us better understand how they are generated. Finally, future applications of the model will include making it publicly available to the community as well as incorporating it into phase-averaged deep-water models such as WAVEWATCH III™ using the RPA mechanism described here.

, the interaction coefficient is

, the interaction coefficient is

refers to the integer value.

refers to the integer value.