1. Introduction

The 2016 presidential elections of America were one of the most acrimonious and confrontational campaigns in the history of America. In fact, this was the only election in American history that left the world astonished as the last ballots were counted, because of its controversial and divisive election campaign (

Nuruzzaman 2017). Studies reveal that the election of Donald J. Trump, despite his lack of political background, as the 45th President was a surprise to many international politicians, pundits, and citizens, including his own followers and party leaders (

Gabriel et al. 2018). In this historic election race, the Republican candidate Donald J. Trump won against the ex-secretary of the State and Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton by 77 electoral colleges’ votes (

Lilleker 2016).

Extraordinary political rhetoric, outbursts in distasteful discriminatory tones, and anti-Muslim invectives blemished the campaign of United States (US) Presidential Elections of 2016 (

Nuruzzaman 2017). During this campaign, Donald Trump promised Americans that he would ban Islam. Later, he attempted to ban Muslims’ entry in the United States (

Husain 2018). Throughout the 2015–16 election campaigning period, Trump’s speeches and announcements were a source of controversy and outrage not only in the United States, but also around the globe. In addition, it has been pointed out (

Tesler 2018) that, after the San Bernardino attacks in December 2015, former President Barack Obama asked Americans for justice and tolerance towards the Muslim community. He emphasized that America is at war against terrorism, not Islam. The very next day, Donald Trump presented his Muslim Ban proposal in response to Obama’s call for tolerance and solidarity with Muslims. His own party leaders, such as Mitch McConnel, Paul Ryan, and Mike Pence, also criticized this controversial ‘

Muslims Ban’.

Francia (

2018) argued that former Secretary, Senator, as well as Democratic Presidential Candidate Hillary Clinton, focused on distinctive and modest policies that were in favor of reducing abortions, and put an emphasis upon education, foster parenting, and the rapid economic growth of the country. In contrast, the Republican candidate Donald Trump, apart from trade and economy, was focused on several controversial issues, such as immigration, terrorism, and security (

McCaw 2016). It is significant that in the attempt to endorse his political agenda, he specifically focused upon Muslims as a grave issue, and likely toyed with the public pulses, which resulted in an unpredictable election result.

Hence, it is from this background that this article highlights Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric in his most controversial statement on the Muslims ban during the campaign. This article specifically focuses upon Trump’s discursive strategies, and Islamophobic rhetoric, which is based upon the dichotomous binaries of the self and other, where the other is de-legitimized.

Kazi (

2017) argued that the portrayal of Muslims as negative stereotypes in the global media emerged during 9/11 and has remained prevalent over the years.

Powell (

2018) claimed that after 9/11, Islamophobic and anti-Muslim sentiments have grown in the US, only because of the media framing that resulted in a barrier to halt immigration from Islamic countries. During the 2016 Elections, the Republican Presidential Candidate Donald J. Trump raised anti-Muslim sentiments that became a compellingly hot topic during the 2016 presidential elections. Therefore, in the current study, the researchers are interested in exploring how Trump presented himself as an Islamophobe in positive terms.

2. Understanding and Researching Islamophobia in the 2016 Presidential Elections of United States

The term Islamophobia has been derived from the word ‘Islam’ with the suffix ‘phobia’, which means ‘fear of Islam’, or in other words ‘hatred towards Muslims’.

Evolvi (

2018) claimed that Islamophobia could be traced back to the 7th Century due to the ‘

Orientalist’ views of the Arab world. However, in the United States, the term Islamophobia has become one of the most debatable discourses after 9/11. In contrast,

Bazian (

2018) mentioned that Islamophobia has emerged from the ‘

Clash of Civilizations’ and it can be linked with the Huntington’s concept of ‘

Islamic Extremism’. In fact, Islamophobia is the unfounded hostility against the Muslim community around the world. Similarly,

Waikar (

2018) argued that the notion of Islamophobia is one of the most significant forms of racism and discrimination. In the same line, the term Islamophobia can highlight the broad range of prejudices, discrimination, racism, and hatred towards Islam and Muslims by Westerners (

Drabu 2018). As such, while debating Islamophobia, global politics have been associated with the negative perceptions and stereotyping of Islam and Muslims with significant support from the global media. Finally, in a broad context,

Islam (

2018) mentioned that Islamophobia is an umbrella term that could target people or property associated or perceived to be associated with Islam and Muslims.

In recent years, Islamophobia has become a most effective political concept that is employed in a vast range of current research. Many researchers have used this term to classify the roots, consequences, magnitudes, history, and intensity of anti-Islamic and anti-Muslim feelings and sentiments. In addition, it is a developing concept in the social sciences, being referred to as a generic, narrow, and vague concept that changes from time to time (

Bleich 2012). In this regard, renowned scholars are of the view that it is social anxiety and stress towards the Islam and Muslim cultures across the globe, while some are of the view that it refers to the rejection of Muslims’ religion due to a violent and interrelated connection with terrorism at large.

Similarly,

Semati (

2010) argued that Islamophobia is all about the fear of Muslims and the fear of the Islamic faith. It is an extensively widespread fear-laden discourse that consists of one-sided judgments that Islam is the enemy and, as such, it is a dangerous faith as far as westerners are concerned. Islamophobia, then, is a negative conception of Islam and Muslims that is considered discordant by Euro-Americans.

In a recent study,

Terman (

2017) claimed that the United States’ mainstream media always highlights the notion that Muslims are distinctly sexist and extremists in nature. According to this study, there is rapid-growing anxiety and misconception about Islam’s compatibility with the West, especially in terms of American values, such as equality, civility, and tolerance. Similarly, another study reveals that the United States media portrays Muslim communities as clearly misogynistic, barbaric, uncivilized, and always a threat to American values (

Sides and Gross 2013). Similarly, the Pew Research Centre reported that Americans’ views towards Muslims are significantly less favorable as compared to all other minorities within the country, because of their association with the 9/11 incident and growing Muslim-related terrorism across the globe. Furthermore,

Lajevardi and Oskooii (

2018) claimed that Islam and Muslims had garnered considerable media and political attention, often being portrayed more negatively than other communities in the United States. As such, it is obvious that Islamophobia in the United States is significantly evident. There are almost 37 groups that belong to the inner core Islamophobic network and 32 of an outer group whose focus is not only to promote prejudice against Islam and Muslims, but also engage in supporting Islamophobic themes in the country (

Saylor 2014).

Muslim-Americans found themselves as overtly front and centre on the political affairs within the country when the 2016 Presidential race in the United States had begun. Donald Trump’s calls for a complete shut down for Muslim immigrants were echoed by Ted Cruz, the Republican nominee for the 2016 elections, who made strong assertions on increasing security involving the shadowing of Muslims after the attacks in Brussels.

Kazi (

2017) claimed that Islamophobia was a trademark of the 2016 elections, most disreputably personified by the Trump’s campaign. His Muslim-immigration ban received raucous applause from his supporters, although party leaders ostensibly condemned his statement. In the report of the Council on the American-Islamic Relations, Nihad Awad, executive director of CAIR, revealed that anger and fear towards Muslim-Americans have now moved from the fringes of American society to mainstream politics and media.

Returning to the Presidential Elections of 2016, Donald Trump was seen to be constantly spreading anti-Muslim sentiments during his long campaign, and often targeted his Democratic opponents regarding the Muslim issue. Similarly, Republican candidate Dr. Ben Carson argued that Islam is totally ‘

inconsistent’ with the American constitution, and hence no Muslim should be elected as President of the United States (

Kazi 2017). Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal also gave a controversial statement—“

Let’s be honest, Islam has a problem”.

Considine (

2017) mentioned that another important Islamophobic narrative during elections season was the fear of the ‘

creeping shariah’ or Islamic law or ways of life, resulting in several states introducing new anti-shariah law bills.

The Democratic candidate during 2016 election, Hillary Clinton, also has not been averse to anti-Muslim remarks. In the past, she enthusiastically supported warfare in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria. As Secretary of State and as Senator, she supported the war against the Muslim world. Moreover, in 2016, after the Orlando massacre at a gay nightclub, Hillary Clinton notoriously called Americans to come forward and return to the ‘spirit of “9/11”; a deeply conservative term following the 9/11 tragedy, which supports the nationalist move that basically gives license to the institutional scapegoating of Muslims, immigrants, Arabs, and South Asians on the basis of structured Islamophobia (

Tolan 2016). The ‘spirit of “9/11” contains watch lists of racialized terror, the PATRIOT Act, anti-Islam and anti-Muslim hate crimes, and an increase in violence towards Muslims within the United States.

However, during the Elections of 2016, she condemned the explicit Islamophobia by Trump arguing that “

Muslims deserve better”. In the 2016 election campaigns, she chose to focus upon the arguments that radical jihadism and radical Islamism is a threat to peace. While replying to a Muslim-American mother of three kids during the presidential debate, she mentioned that Islamophobic comments that were by Donald Trump and Ted Cruz are shameful and against American values (

Kazi 2017).

The candidacy of Donald Trump was empowered in large part by his Islamophobic stance or as some call it, ‘

Islamodiversion’, which means blaming the Muslim community to divert the general public from disastrous economic and political inevitabilities (

Louati 2016). During his election campaign, Donald Trump depicted the United States as a country that was filled with refugees and immigrants from all over the world, including Muslims. Drawing upon the dichotomous self-other binary, he argued that “

Islam hates us”, targeting Muslim-Americans as extremists and terrorists (

Schleifer 2016). Trump also extensively dwelled upon the problems and issues afflicting the United States, such as the rising debt and budget deficit, threats from ISIS, unsecured borders specifically with Mexico, unfair trade agreements with China, unsatisfactory deals with the Muslim world, and counter-terrorism, while depicting innocent white Americans as having been neglected for so many years due to the influx of immigrants.

Emphasizing the fact that Islamophobia has been excessively on the rise in the United States since Trump’s emergence, Abdullah Elshamy published an article in the Al Jazeera World claiming that a network of Islamophobic writers, campaigners, funders, and politicians enabled suitable conditions for Trump to be elected as President. In addition, The Council on American-Islamic Relations also released a report revealing that there was a 57 percent increase in anti-Muslim incidents in 2016 over the previous year, and from 2014–2016, anti-Muslim incidents increased by about 65 percent (

OIC 2017).

Trump’s anti-Islam and anti-Muslim sentiments have been well documented. In an interview on CNN with Anderson Cooper, Trump again argued that “

I think Islam hates us”, focusing once again upon Muslims and Islam as the other. Similarly, his spokesperson Katrina Pierson stated that the notion that “

Islam is the religion of peace” is mere propaganda (

Schleifer 2016). Similarly, on Fox Business, Trump argued “

I would certainly look at the idea of closing mosques within the United States”. After terrorist’ attacks in Paris on 13 November 2015, Trump stated on MSNBC that he would strongly consider closing mosques. On CBS News, he added that ‘If you have people coming out of mosques with hatred and death in their eyes and on their minds, we are going do something’. Furthermore, after Obama chose not to attend the funeral of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, Trump tweeted that

“I wonder if President Obama would have attended the funeral of Justice Scalia if it were held in a Mosque? Very sad that he did not go! After the Brussels attacks, Trump told Fox Business that America was facing several grave concerns because of Muslims (

Hauslohner and Johnson 2017). Furthermore, in justifying his Islamophobia, he has wrongly argued that the Muslim-Americans of New Jersey celebrated after the tragic incidents of 9/11 (

OIC 2016).

Moreover, there were openly crystal-clear pointers that, during the elections campaign, Muslim-Americans were nervous about Trump’s policies and statements. According to the

OIC (

2017) report, there are approximately 3.3 million Muslims living in the United States; there was significant fear along with some reported cases of harassment. During the campaign, more than 700 anti-Muslim and Islamophobic incidents were reported (

OIC 2017). These incidents occurred on the basis of religion, race, political affiliation, and hate. A report that was presented by the Southern Poverty Law Centre stated that anti-Muslim hate groups have nearly tripled in the United States since 2016, from 34 to more than 100. In addition,

Considine (

2017) mentioned that, during the last two months of 2015, Muslim-Americans reported 34 violent incidents involving mosques and other obstacles to worship.

During the campaign, Donald Trump not only stressed anti-Muslim rhetoric, but also proposed harsh laws and policies towards the Muslim-American community. Throughout the whole campaign, he consistently expressed fear of Islam and terror from Muslims all over the world. Thus, it was not at all surprising that Trump came up with a historical statement, ‘Muslim Ban’, which actually reflected his Islamophobic ideology.

3. Critical Discourse Studies as a Research Tool

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), which is currently also known by the term Critical Discourse Studies, is an approach covering almost every aspect of language use in either social or political matters. Most recently, it has been argued that CDA is an increasingly important tool for critical-qualitative-communication research (

Reynolds 2018). It is a qualitative analytical approach for critically describing, interpreting, and explaining the ways through which discourses construct and legitimize social inequalities within a broad context (

Mullet 2018).

Fairclough (

2013) argued that CDA is a method for the analysis of language in relation to power and ideology.

Van Dijk (

1998) has stressed, “Critical Discourse Analysis is a type of discourse analytical research that primarily studies the way social power abuse, dominance, and inequality are enacted, reproduced, and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context”. The foremost focus of CDA is to highlight how applied power in discourse is used to counter and control the minds and actions of the dominant groups, and to protect their interests. CDA thus places particular emphasis on the ways in which certain events or persons are legitimized within certain ideological beliefs. The foremost consideration of CDA is to fill the gap between micro and macro level approaches that are usually established by sociological construction within a society.

Furthermore, CDA has often been used in specific domains in order to analyse their contents and sub-themes. However, there is one incredibly important domain—that of politics where CDA is specifically employed to analyse parliament proceedings, elections campaigns, demonstrations, and, most importantly, political speeches and statements as ideological battles among politicians. Furthermore, it must be noted that CDA provides the tools and methods that are necessary in order to conduct analysis of the dialogical relations between discourse and ideology.

While there are many different approaches and methods within CDA, one of the key concepts that most approaches to CDA explore is the ‘self-other’ schema, which highlights the ‘us versus them’ binary where ‘positive self-presentation’ alongside ‘negative other-representation’ serves to reinforce ideological beliefs, practices, and sentiments. One of the key approaches that focuses upon the self-other schema is the Ideological Square model of Van Dijk.

4. Ideological Square Model

This study focuses on the anti-Muslim and anti-Islam sentiments that were professed by Trump, in his historic statement during the campaign of 2016 Presidential Elections. The most salient aspect of this exploration is the

self versus other schema that is evident in Trump’s Islamophobia. The Ideological Square Model that was presented by Teun A. Van Dijk is appropriate for this study, because it specifically focuses upon the polarizing macro strategy of ‘

positive self-representation and negative other-representation’ (

Van Dijk 1998,

2004,

2006). Several recent studies (

Reynolds 2018); (

Adegoju and Oyebode 2015); (

Cabrejas-Peñuelas and Díez-Prados 2014); and, (

Mazid 2008) suggest that this approach is very relevant and suitable for analysing the type of discourses in the political or media domains where we see the construction of ‘self’ and ‘others’ on the basis of ideological conflicts. Accordingly,

Van Dijk (

1998,

2004,

2006) asserts that this analytical tool is well suited for exploring and highlighting the polarization of ‘us’ vs ‘them’, where the speaker and his or her allies are considered to be ‘us or in-group’, while his or her opponents are placed in the ‘them’ or ‘out-group’ category.

The ideological square emphasizes the oppositions in the self-other representations, where the self or the in-group is often represented as positive, while the other, the out-group, is represented as negative. In the representation of the self, the positive aspects of the self are always highlighted alongside the negative aspects of the other. Furthermore, the negative aspects of the self are almost always mitigated and then played down, alongside the positive aspects of the other. The researchers strongly feel that Van Dijk’s ideological square is an appropriate analytical tool to reveal how Trump always presents himself, along with his supporters and followers (us) as positive, while simultaneously portraying Islam, Muslims and their surrogate terms (them) in a negative way. Similarly, the approach also allows the researchers to highlight how Trump mitigates his own bad actions and statements towards the Muslim community, while hiding or mitigating the Muslims’ contributions and efforts for the betterment of the United States.

Van Dijk (

1998,

2004,

2006) posits that there are two stages of the analysis;

macro-analysis; and,

micro-analysis.

For the macro-analysis,

Van Dijk (

1998,

2004,

2006) has identified four basic strategies that are used in order to legitimize the self and de-legitimize the other;

- 1

emphasize positive things about ‘us’;

- 2

emphasize negative things about ‘them’;

- 3

de-emphasize negative things about ‘us’; and.

- 4

de-emphasize positive things about ‘them’.

Thus, in terms of macro-analysis, the research’s epistemic underpinning focuses upon the self-other binary is as demonstrated below;

Donald Trump: Self, We, Us → In-group

Muslims: Others, They, Them → Out-group

In terms of the micro-analysis, this model comprises 25 key terms or can be said as rhetorical discursive strategies;

Actor description, authority, burden, categorization, comparison, consensus, counterfactual, disclaimer, euphemism, evidentiality, argumentation, illustration/example, generalization, hyperbole, implication, irony, lexicalization, metaphor, national self-glorification, norm expression, number game, polarization (us-them), populism, presupposition, vagueness, and victimization. (

Van Dijk 2006).

A brief description of each term is as follows.

Actor Description: Actor description normally provides detailed information of an entity, such as person, place, or thing, as well as the way that this entity plays its role in a social or political context either positively or negatively. As such, ingroup members tend to be described in a positive or neutral way whereas outgroup members simultaneously in a negative way.

Authority: Van Dijk argued that, by authority, we could take the meaning that mentioning authorities to support one’s claim on a statement. These authorities are: organization, people who considered as moral leaders and experts, international organizations, scholars, media, church, or the courts.

Burden (Topos): It refers to the human or financial loss of a specific group whether small or as big as a nation and to victimize the group or touch the feelings of the target audience.

Categorization: It means assigning people to different groups or in other words, it is applied to classify people regarding their opinions and acts such as religious or political ones as Van Dijk says, “People tend to categorize people”.

Comparison: By comparison, we could simply mean to determine the similarities and differences between two entities, like people, places, events, things, etc. As such, the comparison in discourse according to the Van Dijk, “compare ingroups and outgroups”, whereas outgroups are always compared negatively and ingroups positively and vice-versa.

Consensus: In general, consensus often established fostering and building solidarity and agreement, but for Van Dijk, it is a political strategy where consensus is a “cross-party or national” device to defend a country against external threats or any national issue.

Counterfactuals: It is a persuasive argumentative strategy that is being used to the move of asking for empathy or one could say an expression to highlight what something or somebody would be like if certain conditions are created or not created.

Disclaimer: It is an ideologically-based strategy to determine positive attributes of an entity and then presenting a denial of the attributes using terms, like, ‘but’, ‘yet’, or ‘however’.

Euphemism: Euphemism is a communicative tactic where speaker tries to use milder or less harsh words instead of derogatory or direct terms, for example, ‘decease’ instead of ‘death’ and no one takes it negatively. Van Dijk further argued that euphemism is likely to use in order to mitigate “negative impression formation and the negative acts of the own group”.

Evidentiality: It simply means that the use of hard facts and figures to support speaker’s claim or idea and in other words this strategy is used to provide facts by a discourse producer in order to support his/her own beliefs, opinions, or any information. Van Dijk further adds, “It is an important move to convey objectivity, reliability, validity, and therefore credibility”.

Illustration/Example: It is a communicative strategy that is being used by a speaker to present factual, appropriate or fictional examples in order to make his/her statement more conceivable.

Generalizations: It is a tactic being used to the attribution of negative as well as positive aspects of a specific person or a small group to a large population, for instance, lawyers are hard workers.

Hyperbole: Hyperbole is considered as a linguistic strategy regarding the exaggeration of the language and extra stress on something. As such, Van Dijk stated that hyperbole is a “semantic rhetorical device for the enhancement of meaning”.

Implication: In general, it means simple and briefly expressed or, in other words, it refers to the understanding regarding what is not explicitly expressed in discourse either text or talk. By using this tactic, the speaker always tries to deduct information.

Irony: It is the most important political as well as communicative strategy refers to the deliberate dissimilarity between what is said and what the discourse producer intends to convey through the use of language, often humorously.

Lexicalization: By lexicalization, one could say the use of semantic features of words to portray something or somebody positively or negatively.

Metaphor: Metaphor refers to the contrast or comparison of two phenomena or things that bear no similarity to assign the attributes of one another.

National self-glorification: According to the Van Dijk, it creates a positive representation of a specific country through certain positive references, like history, principles, culture, and traditions.

Norm expression: Norm expression refers to convey the norms of how something should or should not be done and what somebody should and should not do.

Number game: It is an application or strategy that also helps the speaker in making authenticity and credibility by using numbers and statistics. Additionally, Van Dijk argued that “numbers and statistics are the primary means in our culture to persuasively display objectivity, and they routinely characterize news reports in the press”.

Polarization: Polarization strategy means categorization of the people like in-group and their allies with positive features, whereas out-group with negative characteristics.

Populism: Populism is a political strategy where the speaker or political leader wants to gain more and more popularity by placing his/her political ideas and policies.

Presupposition: It is an implicit assumption about the world and is an important political strategy where the speaker uses language in order to achieve his political goals without any evidence or proof.

Vagueness: Vagueness simply means that the use of language by which a speaker or discourse producer creates “uncertainty and ambiguity” when talking about hot issues, like immigration, security, etc. For this purpose, the speaker uses vague expression having no well-defined referents or fuzzy sets.

Victimization: It is a foremost political strategy that is being used for “binary us-them set of in-groups and out-groups” to portray out-group individuals negatively and shows in-group members as the victims of all mishaps or unfair treatments because of the out-group members.

The Ideological Square thus not only reinforces the research’s epistemic underpinning of the ‘self-other’ schema, but it also provides a basis for the investigation of the schema with a series of discursive strategies through which the self-other schema is operationalized in language.

5. Research Methodology

As mentioned above, the study has investigated the portrayal of Islam and Muslims in Donald Trump’s ‘Muslim Ban’ statement during the presidential campaign of 2016 elections. Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump proposed this statement on 7 December 2015 during a rally in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. This ‘

Muslim Ban’ statement was actually a preamble in the further development of Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric and ‘Muslim Ban’ (

Husain 2018).

The researchers used an exclusively qualitative approach, because it does not only explore the what, where, and when, but also why and how the problem appeared, combining elements from the Ideological Square Model in order to scrutinize the purposively selected historic ‘Muslim Ban’ statement in which Trump portrayed Islam, Muslims, and their surrogate terms. In addition, this qualitative study employed CDA, which is a method and a research tool that was developed under the Critical Research Paradigm by constructionists back in the 1970s.

Furthermore, in discourse studies, it should be noted that discourse analysts are not mainly concerned with the sample size of its defined corpus, because a ‘large sample can create an unmanageable amount of data without adding to the analytical outcome’ of the study. Therefore, analytical useful interpretations in discourse studies can also be made with a small sample size of the corpus. (

Waikar 2018). According to Paul

Baker (

2006), in discourse studies, we are always more specific and selective in order to choose the extracts from any speech, interview, or statement on the basis of key words. He further added that, during data collection, the focus should be on the quality of the data, not the quantity. In addition to the qualitative inquiry, researchers are not concerned with how much the sample is representative, but is rather focused on understanding the subtle meanings within the phenomenon. Specifically, Glaser and Strauss have mentioned in 1967 that the sampling procedure in qualitative research is always flexible, ongoing and evolving, while selecting successive data. Thus, the researchers have relied on only one statement: ‘

Muslim Ban’, due to its worldwide significance. This ‘

Muslim Ban’ statement by Trump is considered to be the trademark in understanding his emerging anti-Muslim and anti-Islamic ideology. In the interest of an in-depth analysis, the researchers have divided this ‘Muslim Ban’ statements into four excerpts that are based on different themes. In addition, the researchers also used NVIVO 12-Pro, software for qualitative research studies for data collection and data analysis.

Selection and Background of the ‘Muslim Ban’ Statement by Donald Trump

On 7 December 2015 during a campaign rally in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Donald Trump announced his historic ‘Muslim Ban’ statement. This statement is about 4 min and 17 s and it consists of 217 words. The researchers downloaded the text of this statement at the official website of the American Presidency Project by using the below-mentioned link;

By probing into the background of this anti-Muslim pronouncement, it can be asserted that Donald Trump comes out as an anti-Muslim politician in the United States, who declared that Muslims cause most of the upheavals in America and around the globe. He developed his anti-Muslim pronouncement within a religious setting, censuring Muslims and Islam without a proper comprehension of the concepts of Shariah and Jihad. Before this statement was made, on 2 December 2015, two shooters killed 14 Americans in a mass shooting and attempted bombing during a Christmas party of employees in San Bernardino. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the killers were a Muslim-American couple named Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik, who were identified as of Pakistani descent (

De Atley 2018). After this bloody incident, the global media was critical of the Muslim community and further associated them with global terror.

Therefore, former President Barack Obama called on Americans to show tolerance towards the Muslim community and asserted that America is at war against terrorism, not Islam. The very next day, on 7 December 2015, Donald Trump advanced his Muslim Ban proposal in response to Obama’s call for tolerance and solidarity with Muslims. The proposal is one of the very first controversial statements that were made by Trump as a future presidential candidate. This controversial ‘

Muslims Ban’ was not only criticized internationally, but also by his prominent party leaders (

Tesler 2018). In fact, this was the baseline of Trump’s political ideology, Islamophobic rhetoric and a reflection towards his forthcoming campaign and Presidency to date. In the same stance, he debated that many of the incidents have been instigated by Muslims and have caused declined levels in the economy of America. The sole solution is, as per his perception, to restrain Muslims from provocative activities, pointing to the fact that he would definitely do it when he would be empowered.

6. Data Analysis and Findings

6.1. Computer-Assisted Analysis

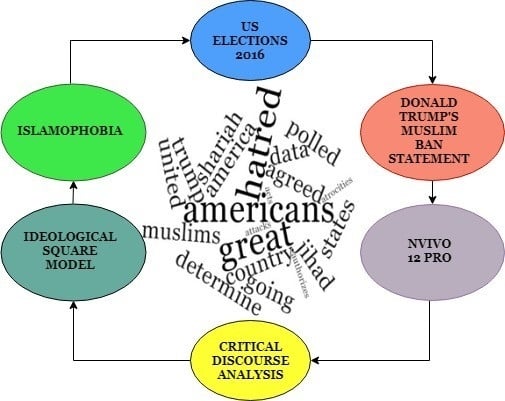

In this stage, the researchers have analyzed the data through NVIVO 12-Pro and are able to obtain some major findings.

Figure 1 shows the overall word cloud of the statement where we can see how Trump used certain words frequently for Islam and Muslims. In addition, by using NVIVO 12 Pro, the pattern of talk and lexical choices of Trump can be seen clearly, as he spoke substantially about Islam and Muslims, both explicitly and implicitly in this ‘

Muslim Ban’ statement.

In the above-mentioned

Figure 1, which clearly shows the choice of terms by Donald Trump towards Islam and Muslims, the focus is mainly upon negative terms, such as hatred, shariah, jihad, violence, etc. By using such lexical choices, Trump openly talked about Islam and Muslims and associated them with hatred and other negative terms, such as terrorism, radicalization, and extremism. The word Americans is also prominent in the word cloud, suggesting the salience of the

us versus them binary. Furthermore,

Figure 2 shows how these frequently used words construct a Tree-Map, where the relationship of the words and their collocates can be seen. It also highlights the hierarchy of certain terms and their consequences, such as hatred, Americans, Jihad, Shariah, etc., indicating the salience of the polarizing

self-other binary, as stated in the Ideological Square.

6.2. Analysis

In this particular stage of the analysis, the researchers have analyzed the ‘Muslim Ban’ statement of Trump by using the Ideological Square Model, which emphasizes the us versus them strategy. The researcher has divided this statement into four excerpts on the basis of the themes, as discussed by Trump.

Excerpt 1. “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on. We have no choice; we have no choice, we have no choice. According to Pew Research, among others, there is great hatred towards Americans by large segments of the Muslim population”.

According to Van Dijk’s terminology, Trump can be regarded as an actor who repeatedly targeted and blamed Muslims in this statement. As such, Trump declares that Muslims should not be permitted to set foot in the United States. For this purpose, he employed authority as a discursive technique by mentioning his name as a powerful man and stressing his future American administration. In fact, the entire extract is supported by the macro strategy of us versus them through the discursive strategy of polarization. He employs the polarization strategy, as he holds Muslims accountable for the destructive and tragic events of 9/11 and all terrorist activities after 9/11 in America. By doing this, he effectively established Muslims as a destructive outgroup that is engaged in terrorist activities. Furthermore, Trump employed the strategy of generalization here, by accusing all Muslims of being responsible and accountable for all types of upheavals and disruption in the world. The generalization strategy is particularly effective, as it collectively assigns blame to a whole group rather than to individuals within the group, thus representing all of them as the out-group.

Donald Trump further argued that Americans should be given strong protection against Muslims. The counterfactual discursive technique has been engaged by Mr Trump, stating that it is deemed necessary to ban the Muslims from entering America as “

we have no choice” except banning them; otherwise, they may cause a serious threat to the lives of Americans. This establishes Muslims as a credible threat to the security of America. By using the Pew Research Centre data to legitimize his arguments through authority and evidentiality, Trump then employed the generalization strategy once again that “large segments of the Muslim population” hate Americans. It is not made clear which segments are referred to, nor is it made clear how many Muslims that he is referring to. This is a particularly effective strategy, as the generalization categorizes all Muslims as the threatening out-group. It can be claimed that the essence in Trump’s Anti-Muslims statement is a visibly Islamophobic setup, pointing to the fact that he intends to establish a complete prohibition on the activities of Muslims in the United States. Therefore, the researchers claim that this highlights the second prominent aspect of Van Dijk’s concept of the Ideological Square (

Van Dijk 1998,

2004,

2006), which is ‘emphasize negative things about them’. In this particular scenario, he negatively pictured the Muslims through the hyperbolical generalization, “

there is great hatred towards Americans by large segments of the Muslim population”. It must be pointed out that, in this extract, and also throughout the entire statement, there is no mention at all of the positive practices of Muslims in the United States. Thus, we argue that, by excluding the positive aspects of Muslims altogether, the afore-mentioned statements in the extract also reflect the fourth aspect of Van Dijk’s Model as ‘de-emphasize positive things about Them’.

Excerpt 2. “Most recently, a poll from the Center for Security Policy released data showing “25% (by the way 1% is unacceptable) of those polled agreed that violence against Americans here in the United States is justified as a part of the global jihad” and 51% of those polled, “agreed that Muslims in America should have the choice of being governed according to Shariah”. Shariah authorizes such atrocities as murder against non-believers who won’t convert beheadings and more unthinkable acts that pose great harm to Americans, especially women”.

In this extract, while talking about a survey report of the Centre for Security Policy, Mr. Trump very successfully employed two strategies, namely the numbers game and authority. The results of the poll in this report show that 25 percent participants agree that it is the Global Jihad that causes violence and turmoil against Americans and 51 percent respondents consider that the Muslims in America should be provided with the liberty to spend their lives as per Sharia (Islamic ways). It is interesting that Trump does not focus upon the majority of the respondents responding favorably towards Muslim rights. In fact, he chooses to focus upon the fact that Shariah is a threat to Americans. Here, Trump employs the technique of polarization by highlighting the misconception that Shariah allows the Muslims a chance to do anything harmful against non-Muslims. There is also a presupposition in Trump’s assertion regarding Shariah in that he makes the implicit assumption that the Americans who voted favorably for Shariah rights for Muslims are not aware of how destructive Shariah is, while Trump himself is very aware. Furthermore, there is also an implicit assumption that Islam is inherently misogynistic. He claimed that it is due to Muslim terrorist activities that Americans, and specifically women, encounter many difficulties and problems. At this point, Trump engages the main discursive technique of hyperbole, as he represents Muslims as religious extremists. In these sentences, Trump’s Islamophobia is particularly prominent and clearly shows prejudice against Jihad and Shariah. Thus, this extract from Trump’s Anti-Muslims statement depicts the second feature of Van Dijk’s model and at the same time negativity stresses against Muslims, and argues for the prevention of them from entering America. It also highlights the fourth feature of the model, named as ‘de-emphasizing positive things about them’, as Trump completely disregarded and passed over all the constructive and worthwhile aspects of the Muslims’ community in America.

Excerpt 3. “Without looking at the various polling data, it is obvious to anybody the hatred is beyond comprehension. Where this hatred comes from and why we will have to determine. Until we are able to determine and understand this problem and the dangerous threat it poses, our country cannot be the victims of horrendous attacks by people that believe only in Jihad, and have no sense of reason or respect for human life”.

In this fragment of Donald J. Trump’s ‘Muslim-Ban’ statement, he employed the two main strategies of generalization and hyperbole that Muslims hate Westerners. Here, he suggested a ban on the Muslims immigration, because he regarded them accountable for all the terrorist activities held in America, especially the recent San Bernardino attacks. Using the same argument, he hyperbolically declared in this extract that the religious hatred of Muslims against the Americans and non-believers is beyond any limits. Therefore, it can be concluded that, here, Trump builds an Islamophobic argument against Islam and Muslims. These expressions mark the first feature of Van Dijk’s model that identifies the emphasis on positive things about ‘us’, because in this statement Trump represents the out-group negatively by stating they “have no sense of reason or respect for human life”, an assertion that positively presupposes that Trump himself, and Americans in general, i.e., the in-group, do have a sense of reason and great respect for human life. The polarization strategy that is used here neglects the reality that Muslim communities in the United States do encounter many hardships.

Furthermore, he claimed that it is easy for him to investigate certain issues as he belonged to a developed country in terms of possessing the latest technology, a healthy economy, and a powerful military. As per his viewpoint, facts about Islamic practices of Jihad are well known, so there is hardly any need to investigate them, and the followers of Jihadi teachings are basically terrorists who do not know the worth of innocent life. Therefore, by this expression of the anti-Islam statement, it can be clearly stated this expression denotes the first feature of the Ideological Square Model, that is to emphasize positive things about ‘us’, as Donald Trump focused upon his positive approach only and presented himself and America as victimized by Islamic terror. At the same time, this expression reflects the second feature of the model, which is to emphasize negative things about ‘them’, because he has exclusively negatively portrayed Muslims. Furthermore, the extract employs the third constituent of the model, which is to de-emphasize negative things about ‘us’. This technique can be seen well when Trump avoided mentioning negative matters, not only about himself, but also for the Americans and stated that he and Americans are upright and justified in their perceptions about the Muslims. The fourth aspect, namely to de-emphasize positive things about ‘them’, can be well seen when Mr Trump showed prejudice against all Muslims, neglecting their contributions towards the betterment of America and withheld all of the positive elements of Muslims, regarding them terrorists and violent due to their religion and beliefs about Shariah and Jihad.

Excerpt 4. “If I win the election for President, we are going to Make America Great Again”.

The “Make America Great Again” expression in Trump’s speech is a slogan that he raised in every stage of the election campaign. Here, the actor Trump tried to develop a vivid connection between him as President of America, with America being associated with its past glory. During the campaign, he has spread his ‘America First’ narrative that concerns Muslims the most, because of its anti-Muslim biases and discrimination. This striking slogan is a compelling populist strategy that is intended to develop bonds between the in-group. Trump maintained a specific sort of categorization in his statement, according to which he regarded himself and his policies good for Americans, whereas all of the ex-politicians and his opponents are implicitly depicted as ineffective. In order to build this impact, he utilized the techniques of populism and comparison. Thus, this slogan is in line with the first feature of the model, because it emphasizes upon positive things about ‘us’ of the Van Dijk’s concept of the Ideological Square (

Van Dijk 1998,

2004,

2006) that the agenda of his party is only to strengthen America once again by implementing harsh immigration laws and security within the country if he became the 45th president of the United States.

7. Discussion

The analysis of the “Muslim Ban” statement reveals that Trump constantly employs the polarizing macro strategy of us versus them, representing Muslims in negative terms while himself and America as positive. The employment of this polarizing strategy is realized through the language that Trump used, being embedded in the many discursive strategies in his use of language. This strategy is deeply divisive, yet populist in that it not only reproduces but also reinforces the negative perception since 9/11 that Muslims and Islam are a constant threat to America. The analysis reveals that Trump does indeed draw upon the self-other binary to keep Islamophobic discourses in regular circulation in the United States. Most significantly, the “Muslim Ban” statement is but a pre-cursor to further statements and policies that were enacted by Trump during and after the elections.

Looking into the life history of Donald J. Trump, it can be said that he was actually not a statesman, but a famous business tycoon and a reality television show star in the United States. He proclaimed his candidature for the American Republican political party on 16 June 2015. From the announcement of his candidature, the elements of an anti-Islam and an anti-Muslim leadership can be seen throughout his whole election campaign. In fact, he has emerged as one of the most anti-Muslim politicians in the history of America.

According to The Bridge Initiative Project on Islamophobia, five years before his candidacy, Trump asserted on The Late Show in the Park 51 Islamic Community Center Manhattan on 4 September 2010, that the United States is at war with Muslims. After the announcement of his candidacy for President, Trump during an interview on 21 October 2015 mentioned that he would look at closing mosques. Similarly, later on, following the Paris attacks of November 2015, Trump asked Americans to

“watch and study the mosques”. On 17 November 2015, Trump tweets that,

“Refugees from Syria are now pouring into our great country. Who knows who they are? Some could be ISIS. Is our president insane?”. After two days, on 19 November 2015, he announced that he would certainly implement a database to track Muslims. Trump also mentioned during a campaign rally in Alabama that Americans need surveillance of certain mosques. He further added that thousands of Muslims cheered while watching the 9/11 incident. Moreover, at a campaign rally in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Trump announced that he had issued a ‘Muslim Ban’ statement. During an interview, Trump mentioned

“We are at war with radical Islam”. Similarly, Trump has also tried to build a consensus with the United Kingdom (UK) regarding the Muslim issue that the UK is also suffering from. In addition, during an interview with Fox News on 13 March 2016, Trump claims that,

“27 percent Muslims around the world are very militant”, whereas in May 2016, while talking to the Fox News anchor Brian Kilmeade, he claimed that this ‘Muslim Ban’ was “Just a suggestion” because nobody had done it yet (

Hamedy 2018). Similarly, on 15 July 2016 Trump proposed another Islamophobic policy: a screening test for Muslims who believe in Shariah law at the time of getting a visa.

Moreover, after becoming the 45 President of the United States, Donald Trump continued his anti-Muslim policies as promised during the campaign and initially signed an executive ban order for seven Muslim countries, namely Iraq, Syria, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen for a period of 90 days (

Husain 2018). After six weeks from the original ban, on 7 March 2015 Trump again revised and signed his second executive order to ‘Ban Muslims’ and mentioned that six Muslim countries would still be banned from entering the United States, except for Iraq. However, the District Court of Hawaii and the Federal Court in Maryland blocked this new executive order by Trump to ban Muslims. Similarly, on 24 September 2017, Trump came up with a new version of the ‘Muslim Ban’ and unveiled travel restrictions from Chad, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, North Korea, and Venezuela.

However, after 18 months of long court proceedings regarding back to back ‘

Muslim Bans’ by Donald Trump, recently, on 26 June 2018, with a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court of the United States finally allowed and upheld the latest version of Trump’s ‘

Muslim Ban’ (

Husain 2018) In this regard, Chief Justice John Roberts argues that

“President Trump did not overstep his bounds whereas the text says nothing about religion” (

Hamedy 2018). This verdict of the Supreme Court has been criticized nationally as well as internationally.

Pitts (

2018) has claimed that this is one of the worst decisions of the Supreme Court in its 229-year history. A professor of Law from Harvard University called this decision similar to the historical Korematsu case of Japanese-American internment during World War II (

Taylor 2018). Furthermore, after this ‘Muslim Ban’ executive order by Trump, there were several nationwide protests at airports in the United States. In addition,

Dehghan (

2017) argued that, due to this ‘Muslim Ban’, Muslims, such as foreign students from Muslim countries, Muslim-American professors and other officials, and Muslim-American journalists who live in the United States for so many years that have citizenship, have been severely affected. It has to be stated clearly here that this implementation of the ‘Muslim Ban’ is, in fact, the completion of Trump’s promise to Americans that was made during the campaign.

8. Conclusions

In the current study, the researchers have argued that Trump emphasized several controversial yet populist issues of America, like immigration, terrorism, and security, to further his anti-Muslim agenda. The current study has also investigated the fact that Trump has portrayed Muslims as a grave issue and presented his anti-Islamic ideology in the form of Islamophobia, while also talking about and dealing with the Muslim community. Donald Trump passed considerable negative comments to denigrate Muslims in his ‘Muslim Ban’ statement. He not only censured Islam and its commandments, like Jihad and laws (Shariah), but also considered sacred places, like mosques, as intolerant. Besides that, Donald J. Trump criticized his political rivals, i.e., Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, openly condemning them for their policies as pro-Islam and pro-Muslims, and particularly, anti-America and anti-Israel policies. According to Trump, the administration of Obama remained unsuccessful in dealing with illegal immigrants who do not possess valid documents for entry into America. Islamophobia can clearly be seen in almost all of his statements during the elections race where he alleged that Muslims are responsible for all terrorist activities, propounding the idea that the Americans should hate Muslims, as the Muslims detest Jews and the Americans.

Trump’s biased approach towards the Muslims can also be seen during the election campaign when he never mentioned the contribution of the Muslim community towards the betterment of American society. Instead, he always portrayed them as terrorists, religious extremists, and labeled them as anti-democratic bodies. Furthermore, he presented many dubious references to prove his viewpoint that Islam stands out as an anti-women religion.

Besides the four macro strategies of

self and

others, twenty-five key rhetorical terms that have been suggested by Van Dijk to investigate the dimensions of an Ideological Square (

Van Dijk 1998,

2004,

2006) have also helped us to explore and investigate the imprints of Islamophobia in Trump’s statement. These discursive techniques strategies have been identified with great density in Trump’s ‘Muslim Ban’ statement. The most frequently used strategies are authority, evidentiality, generalization, presupposition, hyperbole, populism, and categorization. All of these strategies feed into the polarization strategy of

us versus them, where the representation of Islam and Muslims is underpinned by the explicit positioning of them as an out-group entity with negative references.

Thus, it can be seen that Donald Trump has become a prominent right-wing anti-Islam and anti-Muslim political figure for the American Republican political party. Since the very early stage of his political career, he has propounded high levels of Islamophobia. Therefore, it can be concluded from the whole discussion that President Donald J. Trump has employed an anti-Islam and anti-Muslim strategy since the announcement of his candidacy for the presidential race on the Republican card in order to build an affinity between the populist anti-Muslim sentiments of Americans and himself. He has shown extreme bias and discriminatory rhetoric against Muslims and Islam, making it a significant part of his “Make America Great Again” slogan. This study has shown that Trump’s ‘Muslim Ban’ statement was, in fact, a pre-cursor to his future anti-Muslim policies and practices that are in line with his discriminatory ideology.