NADH/NAD+ Redox Imbalance and Diabetic Kidney Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sources of Elevated NADH in Diabetes

3. Pathways of NAD+ Consumption in Diabetes

3.1. The Poly ADP Ribosylase Pathway

3.2. The Sirtuins Pathway

3.3. The CD38 Pathway

3.4. The NAD Kinase Pathway

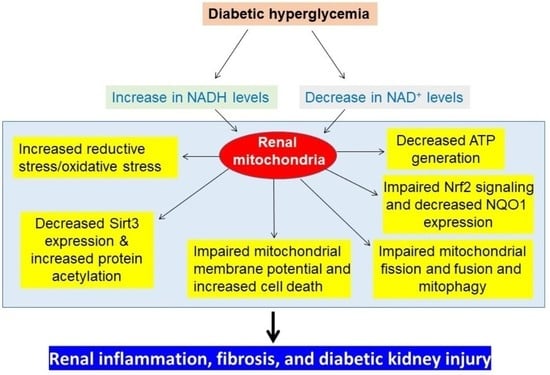

4. Redox Imbalance-linked Mitochondrial Dysfunction in DKD

5. Therapeutic Approaches to Counteracting DKD

5.1. Superoxide Dismutation and Suppression

5.2. Mitochondria-targeted Antioxidants and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Mimetics

5.3. Plant and Herb Derived Antioxidants

5.4. Caloric Restriction

6. Magnitude of Redox Imbalance and Progression of DKD

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Radi, Z.A. Kidney Pathophysiology, Toxicology, and Drug-Induced Injury in Drug Development. Int. J. Toxicol. 2019, 38, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeppen, B.M.; Stanton, B.A. Renal Physiology, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, R.G. Elsevier’s Integrated Physiology; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zorov, D.B.; Filburn, C.R.; Klotz, L.O.; Zweier, J.L.; Sollott, S.J. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: A new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Jang, H.S.; Park, K.M. Reactive oxygen species generated by renal ischemia and reperfusion trigger protection against subsequent renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2010, 298, F158–F166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosca, M.G.; Vazquez, E.J.; Chen, Q.; Kerner, J.; Kern, T.S.; Hoppel, C.L. Oxidation of fatty acids is the source of increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in kidney cortical tubules in early diabetes. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2074–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, P.Z.; Szeto, C.C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 496, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallan, S.; Sharma, K. The Role of Mitochondria in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2016, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Bai, X.; Chen, X. Autophagy and Diabetic Nephropathy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1207, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Tao, P.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Xu, Y. SIRT1: Mechanism and Protective in Diabetic Nephropathy. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoja, C.; Xinaris, C.; Macconi, D. Diabetic Nephropathy: Novel Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 586892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Mi, Y.; Ren, X.; Lian, S.; Kang, J.; Wang, J.; Zang, H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Experimental study on renoprotective effect of intermedin on diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 528, 111224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodhi, A.H.; Ahmad, F.U.; Furwa, K.; Madni, A. Role of Oxidative Stress and Reduced Endogenous Hydrogen Sulfide in Diabetic Nephropathy. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 1031–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.C. Type 1 diabetes mellitus: Much progress, many opportunities. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuch, B.; Dunlop, M.; Proietto, J. Diabetes Research: A Guide for Postgraduates; Harwood Academic Publishers: Reading, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Volfson-Sedletsky, V.; Jones, A., IV; Hernandez-Escalante, J.; Dooms, H. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies to Restore Regulatory T Cell Control of Islet Autoimmunity in Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 635767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol. Res. 2001, 50, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szkudelski, T. Streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetes in the rat. Characteristics of the experimental model. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012, 237, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, S.E.; Cooper, M.E.; Del Prato, S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: Perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet 2014, 383, 1068–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 88, 787–835, ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFronzo, R.A. Insulin resistance: A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Neth. J. Med. 1997, 50, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.H. Type 2 Diabetes, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Ghani, M.A.; DeFronzo, R.A. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. In Oxidative Stress in Aging; Miwa, S., Beckman, K.B., Muller, F.L., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Maqbool, M.; Cooper, M.E.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.A.M. Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Semin. Nephrol. 2018, 38, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Ye, D.; Gao, C.; Huang, Q.; Gui, D. Mechanism of progression of diabetic kidney disease mediated by podocyte mitochondrial injury. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 8023–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K.; McCue, P.; Dunn, S.R. Diabetic kidney disease in the db/db mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2003, 284, F1138–F1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tesch, G.H.; Lim, A.K. Recent insights into diabetic renal injury from the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2011, 300, F301–F310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.J.; Gonzalez, E.A. Vitamin D and the kidney. Mo. Med. 2012, 109, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dusso, A.S. Kidney disease and vitamin D levels: 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, and VDR activation. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2011, 1, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iida, K.; Shinki, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; DeLuca, H.F.; Kurokawa, K.; Suda, T. A possible role of vitamin D receptors in regulating vitamin D activation in the kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 6112–6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Souma, T.; Suzuki, N.; Yamamoto, M. Renal erythropoietin-producing cells in health and disease. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, N.; Yamamoto, M. Roles of renal erythropoietin-producing (REP) cells in the maintenance of systemic oxygen homeostasis. Pflugers Arch. 2016, 468, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Xie, J.; Chen, N. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-Proline Hydroxylase Inhibitor in the Treatment of Renal Anemia. Kidney Dis. 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galuska, D.; Pacal, L.; Kankova, K. Pathophysiological Implication of Vitamin D in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2021, 46, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Han, F.; Ren, J.; Hu, Z. Vitamin D deficiency and related risk factors in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J. Int. Med. Res. 2016, 44, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xie, S.; Huang, L.; Cao, W.; Hu, Y.; Sun, H.; Cao, L.; Liu, K.; Liu, C. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and diabetic kidney disease in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, S.F.; Tarng, D.C. Anemia in patients of diabetic kidney disease. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2019, 82, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, S.K.; Singh, H.P.; Sonkar, G.K.; Pandey, S. Association of Vitamin D and secondary hyperparathyroidism with anemia in diabetic kidney disease. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2018, 7, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Tsalamandris, C.; MacIsaac, R.; Jerums, G. Anaemia in diabetes: An emerging complication of microvascular disease. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2005, 1, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanan, R.; Spiro, J.R.; Mathieson, P.W.; Smith, R.M. Impact of diabetes on haemoglobin levels in renal disease. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, B.; Ruiz, M.A.; Chakrabarti, S. Oxidative-stress-induced epigenetic changes in chronic diabetic complications. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 91, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naruse, K.; Rask-Madsen, C.; Takahara, N.; Ha, S.W.; Suzuma, K.; Way, K.J.; Jacobs, J.R.; Clermont, A.C.; Ueki, K.; Ohshiro, Y.; et al. Activation of vascular protein kinase C-beta inhibits Akt-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase function in obesity-associated insulin resistance. Diabetes 2006, 55, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurel, Z.; Sieg, K.M.; Shallow, K.D.; Sorenson, C.M.; Sheibani, N. Retinal O-linked N-acetylglucosamine protein modifications: Implications for postnatal retinal vascularization and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Mol. Vis. 2013, 19, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McLarty, J.L.; Marsh, S.A.; Chatham, J.C. Post-translational protein modification by O-linked N-acetyl-glucosamine: Its role in mediating the adverse effects of diabetes on the heart. Life Sci. 2013, 92, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lovestone, S.; Smith, U. Advanced glycation end products, dementia, and diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4743–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mellor, K.M.; Brimble, M.A.; Delbridge, L.M. Glucose as an agent of post-translational modification in diabetes—New cardiac epigenetic insights. Life Sci. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.J. Pathogenesis of Chronic Hyperglycemia: From Reductive Stress to Oxidative Stress. J. Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 137919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yan, L.J. Redox imbalance stress in diabetes mellitus: Role of the polyol pathway. Animal Model. Exp. Med. 2018, 1, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.; Youdim, M.B.; Riederer, P. Redox imbalance. Cell Tissue Res. 2004, 318, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, M.R.; Sowers, J.R. Redox imbalance in diabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Zheng, H.; Yan, L.J. Sources and implications of NADH/NAD+ redox imbalance in diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2016, 9, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhan, M.; Usman, I.M.; Sun, L.; Kanwar, Y.S. Disruption of renal tubular mitochondrial quality control by Myo-inositol oxygenase in diabetic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 1304–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miranda-Diaz, A.G.; Pazarin-Villasenor, L.; Yanowsky-Escatell, F.G.; Andrade-Sierra, J. Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Nephropathy with Early Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 7047238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yanar, K.; Coskun, Z.M.; Beydogan, A.B.; Aydin, S.; Bolkent, S. The effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on Kruppel-like factor-4 expression, redox homeostasis, and inflammation in the kidney of diabetic rat. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 16219–16228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, R.G.; Guedes, G.D.S.; Vasconcelos, S.M.L.; Santos, J.C.F. Kidney Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: Cross-Linking between Hyperglycemia, Redox Imbalance and Inflammation. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019, 112, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilton, R.G.; Baier, L.D.; Harlow, J.E.; Smith, S.R.; Ostrow, E.; Williamson, J.R. Diabetes-induced glomerular dysfunction: Links to a more reduced cytosolic ratio of NADH/NAD+. Kidney Int. 1992, 41, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, X.; Li, R.; Yan, L.J. Roles of Pyruvate, NADH, and Mitochondrial Complex I in Redox Balance and Imbalance in β Cell Function and Dysfunction. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 512618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, X.; Wu, J.; Jing, S.; Yan, L.J. Hyperglycemic stress and carbon stress in diabetic glucotoxicity. Aging Dis. 2016, 7, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ido, Y. Pyridine nucleotide redox abnormalities in diabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.S.; Ho, E.C.; Lam, K.S.; Chung, S.K. Contribution of polyol pathway to diabetes-induced oxidative stress. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, S233–S236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunlop, M. Aldose reductase and the role of the polyol pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2000, 77, S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fantus, I.G. The pathogenesis of the chronic complications of the diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol. Rounds 2002, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzilias, A.A.; Whiteside, C.I. Cellular mechanisms of glucose-induced myo-inositol transport upregulation in rat mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267, F459–F466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancey, P.H.; Haner, R.G.; Freudenberger, T.H. Effects of an aldose reductase inhibitor on organic osmotic effectors in rat renal medulla. Am. J. Physiol. 1990, 259, F733–F738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownlee, M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Veeresham, C.; Rama Rao, A.; Asres, K. Aldose reductase inhibitors of plant origin. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Gamal, H.; Eid, A.H.; Munusamy, S. Renoprotective Effects of Aldose Reductase Inhibitor Epalrestat against High Glucose-Induced Cellular Injury. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5903105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, K.; Pal, P.B.; Sonowal, H.; Srivastava, S.K.; Ramana, K.V. Aldose Reductase Inhibitor Protects against Hyperglycemic Stress by Activating Nrf2-Dependent Antioxidant Proteins. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 6785852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artasensi, A.; Pedretti, A.; Vistoli, G.; Fumagalli, L. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review of Multi-Target Drugs. Molecules 2020, 25, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonowal, H.; Ramana, K.V. Development of aldose reductase inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory disorders and cancer: Current drug design strategies and future directions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannapureddy, S.; Sharma, M.; Yepuri, G.; Schmidt, A.M.; Ramasamy, R. Aldose Reductase: An Emerging Target for Development of Interventions for Diabetic Cardiovascular Complications. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 636267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Ying, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, P.; Ji, X.; Chi, T.; Zou, L.; Wang, S.; He, Z. WJ-39, an Aldose Reductase Inhibitor, Ameliorates Renal Lesions in Diabetic Nephropathy by Activating Nrf2 Signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 7950457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzen, S.; Buyukbingol, E. Recent studies of aldose reductase enzyme inhibition for diabetic complications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 1329–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.B.; Ramana, K.V. Aldose reductase inhibition: Emerging drug target for the treatment of cardiovascular complications. Recent Pat. Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2010, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, C.; Watada, H.; Azuma, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kanazawa, A.; Ikeda, F.; Yoshihara, T.; Fujitani, Y.; Hirose, T.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Aldose reductase inhibitor, epalrestat, reduces lipid hydroperoxides in type 2 diabetes. Endocr. J. 2009, 56, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tang, J.; Du, Y.; Petrash, J.M.; Sheibani, N.; Kern, T.S. Deletion of aldose reductase from mice inhibits diabetes-induced retinal capillary degeneration and superoxide generation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, J.R.; Chang, K.; Frangos, M.; Hasan, K.S.; Ido, Y.; Kawamura, T.; Nyengaard, J.R.; van den Enden, M.; Kilo, C.; Tilton, R.G. Hyperglycemic pseudohypoxia and diabetic complications. Diabetes 1993, 42, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ido, Y.; Williamson, J.R. Hyperglycemic cytosolic reductive stress ‘pseudohypoxia’: Implications for diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997, 38, 1467–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Garcia Canaveras, J.C.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Liang, L.; Jang, C.; Mayr, J.A.; Zhang, Z.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Zhan, L.; et al. Serine Catabolism Feeds NADH when Respiration Is Impaired. Cell. Metab. 2020, 31, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harden, W.R., III; Barlow, C.H.; Simson, M.B.; Harken, A.H. Temporal relation between onset of cell anoxia and ischemic contractile failure. Myocardial ischemia and left ventricular failure in the isolated, perfused rabbit heart. Am. J. Cardiol. 1979, 44, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.D.; Xu, S.C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, J.C.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.H.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.P.; Zhou, Z. Disturbance of aerobic metabolism accompanies neurobehavioral changes induced by nickel in mice. Neurotoxicology 2013, 38, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doke, T.; Ishimoto, T.; Hayasaki, T.; Ikeda, S.; Hasebe, M.; Hirayama, A.; Soga, T.; Kato, N.; Kosugi, T.; Tsuboi, N.; et al. Lacking ketohexokinase-A exacerbates renal injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Metabolism 2018, 85, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, E.M.; El-Maraghy, N.N.; Ahmed, A.F.; Ali, A.A.; El-Bassossy, H.M. PARP inhibition ameliorates nephropathy in an animal model of type 2 diabetes: Focus on oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2017, 390, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massudi, H.; Grant, R.; Guillemin, G.J.; Braidy, N. NAD+ metabolism and oxidative stress: The golden nucleotide on a crown of thorns. Redox Rep. 2012, 17, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov, A.; Kulikova, V.; Ziegler, M. The human NAD metabolome: Functions, metabolism and compartmentalization. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 50, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieper, A.A.; Brat, D.J.; Krug, D.K.; Watkins, C.C.; Gupta, A.; Blackshaw, S.; Verma, A.; Wang, Z.Q.; Snyder, S.H. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-deficient mice are protected from streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3059–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masutani, M.; Suzuki, H.; Kamada, N.; Watanabe, M.; Ueda, O.; Nozaki, T.; Jishage, K.; Watanabe, T.; Sugimoto, T.; Nakagama, H.; et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase gene disruption conferred mice resistant to streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2301–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vedantham, S.; Thiagarajan, D.; Ananthakrishnan, R.; Wang, L.; Rosario, R.; Zou, Y.S.; Goldberg, I.; Yan, S.F.; Schmidt, A.M.; Ramasamy, R. Aldose reductase drives hyperacetylation of Egr-1 in hyperglycemia and consequent upregulation of proinflammatory and prothrombotic signals. Diabetes 2014, 63, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sauve, A.A. Sirtuin chemical mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 1591–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Yan, L.J. Redox imbalance and mitochondrial abnormalities in the diabetic lung. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chini, C.C.S.; Tarrago, M.G.; Chini, E.N. NAD and the aging process: Role in life, death and everything in between. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 455, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzi, A.; Sturla, L.; Heine, M.; Fischer, A.W.; Spinelli, S.; Magnone, M.; Sociali, G.; Parodi, A.; Fenoglio, D.; Emionite, L.; et al. CD38 downregulation modulates NAD+ and NADP (H) levels in thermogenic adipose tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peclat, T.R.; Shi, B.; Varga, J.; Chini, E.N. The NADase enzyme CD38: An emerging pharmacological target for systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2020, 32, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, A.J.; Kale, A.; Perrone, R.; Lopez-Dominguez, J.A.; Pisco, A.O.; Kasler, H.G.; Schmidt, M.S.; Heckenbach, I.; Kwok, R.; Wiley, C.D.; et al. Senescent cells promote tissue NAD+ decline during ageing via the activation of CD38+ macrophages. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 1265–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Liu, N.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Wu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Q. CD38: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Cardiovascular Disease. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Adebanjo, O.A.; Moonga, B.S.; Corisdeo, S.; Anandatheerthavarada, H.K.; Biswas, G.; Arakawa, T.; Hakeda, Y.; Koval, A.; Sodam, B.; et al. CD38/ADP-ribosyl cyclase: A new role in the regulation of osteoclastic bone resorption. J. Cell. Biol. 1999, 146, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, B.; Wang, W.; Korman, B.; Kai, L.; Wang, Q.; Wei, J.; Bale, S.; Marangoni, R.G.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Miller, S.; et al. Targeting CD38-dependent NAD+ metabolism to mitigate multiple organ fibrosis. iScience 2021, 24, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, Y.; Kitada, M.; Xu, J.; Monno, I.; Koya, D. CD38 inhibition by apigenin ameliorates mitochondrial oxidative stress through restoration of the intracellular NAD+/NADH ratio and Sirt3 activity in renal tubular cells in diabetic rats. Aging 2020, 12, 11325–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, P.M.; Bansal, N.; Kerrigan, J.E.; Abali, E.E.; Scotto, K.W.; Bertino, J.R. NAD+ Kinase as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 5189–5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, R. MNADK, a Long-Awaited Human Mitochondrion-Localized NAD Kinase. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Molecular properties, functions, and potential applications of NAD kinases. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2009, 41, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoxhaj, G.; Ben-Sahra, I.; Lockwood, S.E.; Timson, R.C.; Byles, V.; Henning, G.T.; Gao, P.; Selfors, L.M.; Asara, J.M.; Manning, B.D. Direct stimulation of NADP+ synthesis through Akt-mediated phosphorylation of NAD kinase. Science 2019, 363, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Hoshino, A.; Zheng, H.D.; Morley, M.; Arany, Z.; Rabinowitz, J.D. NADPH production by the oxidative pentose-phosphate pathway supports folate metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, N.Y.; Stanton, R.C. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase and the kidney. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2017, 26, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.J.; Christians, E.S.; Liu, L.; Xiao, X.; Sohal, R.S.; Benjamin, I.J. Mouse heat shock transcription factor 1 deficiency alters cardiac redox homeostasis and increases mitochondrial oxidative damage. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 5164–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogura, Y.; Kitada, M.; Monno, I.; Kanasaki, K.; Watanabe, A.; Koya, D. Renal mitochondrial oxidative stress is enhanced by the reduction of Sirt3 activity, in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Redox Rep. 2018, 23, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forbes, J.M.; Coughlan, M.T.; Cooper, M.E. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turrens, J.F. Superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biosci. Rep. 1997, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrens, J.F.; Alexandre, A.; Lehninger, A.L. Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985, 237, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujic, A.; Koo, A.N.M.; Prag, H.A.; Krieg, T. Mitochondrial redox and TCA cycle metabolite signaling in the heart. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 166, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.R.; An, E.J.; Kim, J.; Bae, Y.S. Function of NADPH Oxidases in Diabetic Nephropathy and Development of Nox Inhibitors. Biomol. Ther. 2020, 28, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, S.; Dalla Gassa, A.; Tomei, P.; Lupo, A.; Zaza, G. Mitochondria: A new therapeutic target in chronic kidney disease. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.; Luo, X.; Thangthaeng, N.; Sumien, N.; Chen, Z.; Rutledge, M.A.; Jing, S.; Forster, M.J.; Yan, L.J. Pancreatic mitochondrial complex I exhibits aberrant hyperactivity in diabetes. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 11, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drose, S.; Brandt, U. Molecular mechanisms of superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 748, 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.J.; Sumien, N.; Thangthaeng, N.; Forster, M.J. Reversible inactivation of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase by mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Yan, L.J. Protein Modifications as Manifestations of Hyperglycemic Glucotoxicity in Diabetes and Its Complications. Biochem. Insights 2016, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, L.J.; Lodge, J.K.; Traber, M.G.; Matsugo, S.; Packer, L. Comparison between copper-mediated and hypochlorite-mediated modifications of human low density lipoproteins evaluated by protein carbonyl formation. J. Lipid Res. 1997, 38, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, B.N.; Shigenaga, M.K. Oxidants are a major contributor to aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 663, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefek, M.; Gajdosik, A.; Tribulova, N.; Navarova, J.; Volkovova, K.; Weismann, P.; Gajdosikova, A.; Drimal, J.; Mihalova, D. The pyridoindole antioxidant stobadine attenuates albuminuria, enzymuria, kidney lipid peroxidation and matrix collagen cross-linking in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 24, 565–571. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.X.; Luo, S.B.; Jiang, P.; Xia, M.M.; Hei, A.L.; Mao, Y.H.; Li, C.B.; Hu, G.X.; Cai, J.P. Increased Oxidative Damage of RNA in Early-Stage Nephropathy in db/db Mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 2353729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.; Luo, X.; Jing, S.; Yan, L.J. Two-dimensional gel electrophoretic detection of protein carbonyls derivatized with biotin-hydrazide. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1019, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhargava, P.; Schnellmann, R.G. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, G.C.; Coughlan, M.T. Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy: The beginning and end to diabetic nephropathy? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 1917–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yi, H.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Shong, M. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response and mitohormesis: A perspective on metabolic diseases. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61, R91–R105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvan, D.L.; Green, N.H.; Danesh, F.R. The hallmarks of mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanga, B.A.; Badal, S.S.; Wang, Y.; Galvan, D.L.; Chang, B.H.; Schumacker, P.T.; Danesh, F.R. Dynamin-Related Protein 1 Deficiency Improves Mitochondrial Fitness and Protects against Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2733–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galvan, D.L.; Long, J.; Green, N.; Chang, B.H.; Lin, J.S.; Schumacker, P.; Truong, L.D.; Overbeek, P.; Danesh, F.R. Drp1S600 phosphorylation regulates mitochondrial fission and progression of nephropathy in diabetic mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2807–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; Xiong, L.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Peng, X.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission promotes renal fibroblast activation and fibrogenesis. Cell. Death Dis. 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, K.; Li, M.; Liang, W.; Que, H. Sirt3 overexpression alleviates hyperglycemia-induced vascular inflammation through regulating redox balance, cell survival, and AMPK-mediated mitochondrial homeostasis. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. 2019, 39, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Katayama, A.; Terami, T.; Han, X.; Nunoue, T.; Zhang, D.; Teshigawara, S.; Eguchi, J.; Nakatsuka, A.; Murakami, K.; et al. Translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane 44 alters the mitochondrial fusion and fission dynamics and protects from type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 2015, 64, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agil, A.; Chayah, M.; Visiedo, L.; Navarro-Alarcon, M.; Rodriguez Ferrer, J.M.; Tassi, M.; Reiter, R.J.; Fernandez-Vazquez, G. Melatonin Improves Mitochondrial Dynamics and Function in the Kidney of Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Usman, I.; Yu, J.; Ruan, L.; Bian, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, S.; Sun, L.; Kanwar, Y.S. Perturbations in mitochondrial dynamics by p66Shc lead to renal tubular oxidative injury in human diabetic nephropathy. Clin. Sci. 2018, 132, 1297–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Emancipator, S.N.; Kern, T.; Simonson, M.S. High glucose evokes an intrinsic proapoptotic signaling pathway in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coughlan, M.T.; Higgins, G.C.; Nguyen, T.V.; Penfold, S.A.; Thallas-Bonke, V.; Tan, S.M.; Ramm, G.; van Bergen, N.J.; Henstridge, D.C.; Sourris, K.C.; et al. Deficiency in Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Recapitulates Chronic Kidney Disease via Aberrant Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kostic, S.; Hauke, T.; Ghahramani, N.; Filipovic, N.; Vukojevic, K. Expression pattern of apoptosis-inducing factor in the kidneys of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Acta Histochem. 2020, 122, 151655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Mitophagy regulates macrophage phenotype in diabetic nephropathy rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 494, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Z.; Jing, K.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ye, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, C.; Pan, Q.; Liu, W.J.; Liu, H.F. Mechanisms and Functions of Mitophagy and Potential Roles in Renal Disease. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Padman, B.S.; Lazarou, M. Deciphering the Molecular Signals of PINK1/Parkin Mitophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, M.Z.; Macleod, K.F. In Brief: Mitophagy: Mechanisms and role in human disease. J. Pathol. 2016, 240, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, M.F.; Franzen, S.; Catrina, S.B.; Dallner, G.; Hansell, P.; Brismar, K.; Palm, F. Coenzyme Q10 prevents GDP-sensitive mitochondrial uncoupling, glomerular hyperfiltration and proteinuria in kidneys from db/db mice as a model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fabris, B.; Candido, R.; Armini, L.; Fischetti, F.; Calci, M.; Bardelli, M.; Fazio, M.; Campanacci, L.; Carretta, R. Control of glomerular hyperfiltration and renal hypertrophy by an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor prevents the progression of renal damage in hypertensive diabetic rats. J. Hypertens. 1999, 17, 1925–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.L.; Sourris, K.C.; Harcourt, B.E.; Thallas-Bonke, V.; Penfold, S.; Andrikopoulos, S.; Thomas, M.C.; O’Brien, R.C.; Bierhaus, A.; Cooper, M.E.; et al. Disparate effects on renal and oxidative parameters following RAGE deletion, AGE accumulation inhibition, or dietary AGE control in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2010, 298, F763–F770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brand, M.D. Riding the tiger—Physiological and pathological effects of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generated in the mitochondrial matrix. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 55, 592–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D.; Goncalves, R.L.; Orr, A.L.; Vargas, L.; Gerencser, A.A.; Borch Jensen, M.; Wang, Y.T.; Melov, S.; Turk, C.N.; Matzen, J.T.; et al. Suppressors of Superoxide-H2O2 Production at Site IQ of Mitochondrial Complex I Protect against Stem Cell Hyperplasia and Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Apakkan Aksun, S.; Ozmen, B.; Ozmen, D.; Parildar, Z.; Senol, B.; Habif, S.; Mutaf, I.; Turgan, N.; Bayindir, O. Serum and urinary nitric oxide in Type 2 diabetes with or without microalbuminuria: Relation to glomerular hyperfiltration. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2003, 17, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wong, H.S.; Brand, M.D. Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in the mitochondrial matrix is dominated by site IQ of complex I in diverse cell lines. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.W.; Shen, C.J.; Tung, Y.T.; Chen, H.L.; Chen, Y.H.; Chang, W.H.; Cheng, K.C.; Yang, S.H.; Chen, C.M. Extracellular superoxide dismutase ameliorates streptozotocin-induced rat diabetic nephropathy via inhibiting the ROS/ERK1/2 signaling. Life Sci. 2015, 135, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, M.A.; Wong, H.S.; Brand, M.D. Use of S1QELs and S3QELs to link mitochondrial sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation to physiological and pathological outcomes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plecita-Hlavata, L.; Engstova, H.; Jezek, J.; Holendova, B.; Tauber, J.; Petraskova, L.; Kren, V.; Jezek, P. Potential of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants to Prevent Oxidative Stress in Pancreatic beta-cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1826303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homma, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Sato, H.; Fujii, J. Superoxide produced by mitochondrial complex III plays a pivotal role in the execution of ferroptosis induced by cysteine starvation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 700, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop, K.A.; Rovini, A.; Hunt, E.G.; Fang, D.; Morris, M.E.; Christie, C.F.; Gooz, M.B.; DeHart, D.N.; Dang, Y.; Lemasters, J.J.; et al. JNK activation and translocation to mitochondria mediates mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death induced by VDAC opening and sorafenib in hepatocarcinoma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 171, 113728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, H.S.; Mezera, V.; Dighe, P.; Melov, S.; Gerencser, A.A.; Sweis, R.F.; Pliushchev, M.; Wang, Z.; Esbenshade, T.; McKibben, B.; et al. Superoxide produced by mitochondrial site IQ inactivates cardiac succinate dehydrogenase and induces hepatic steatosis in Sod2 knockout mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 164, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatinguais, R.; Pradhan, A.; Brown, G.D.; Brown, A.J.P.; Warris, A.; Shekhova, E. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Regulate Immune Responses of Macrophages to Aspergillus fumigatus. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 641495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, A.J.; Bolton, E.A.; Pettigrew, G.J.; Bradley, J.A.; Saeb-Parsy, K.; Murphy, M.P. Protection against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo by the mitochondria targeted antioxidant MitoQ. Redox Biol. 2015, 5, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dare, A.J.; Logan, A.; Prime, T.A.; Rogatti, S.; Goddard, M.; Bolton, E.M.; Bradley, J.A.; Pettigrew, G.J.; Murphy, M.P.; Saeb-Parsy, K. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant MitoQ decreases ischemia-reperfusion injury in a murine syngeneic heart transplant model. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- James, A.M.; Sharpley, M.S.; Manas, A.R.; Frerman, F.E.; Hirst, J.; Smith, R.A.; Murphy, M.P. Interaction of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ with phospholipid bilayers and ubiquinone oxidoreductases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 14708–14718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saretzki, G.; Murphy, M.P.; von Zglinicki, T. MitoQ counteracts telomere shortening and elongates lifespan of fibroblasts under mild oxidative stress. Aging Cell 2003, 2, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, M.Y.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, J. MitoQ protects against high glucose-induced brain microvascular endothelial cells injury via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 145, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, H.; Liao, L.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Tang, B.; et al. MitoQ alleviates LPS-mediated acute lung injury through regulating Nrf2/Drp1 pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 165, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, M.; Ouyang, W.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Lin, X.; Dai, M.; Hu, H.; Tang, H.; Liu, H.; Xia, J.; et al. MitoQ protects against hyperpermeability of endothelium barrier in acute lung injury via a Nrf2-dependent mechanism. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, K.A.; Blanco, L.P.; Buskiewicz, I.; Huang, N.; Gibson, P.C.; Cook, D.L.; Pedersen, H.L.; Yuen, P.S.T.; Murphy, M.P.; Perl, A.; et al. Targeting mitochondrial oxidative stress with MitoQ reduces NET formation and kidney disease in lupus-prone MRL-lpr mice. Lupus Sci. Med. 2020, 7, e000387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chacko, B.K.; Reily, C.; Srivastava, A.; Johnson, M.S.; Ye, Y.; Ulasova, E.; Agarwal, A.; Zinn, K.R.; Murphy, M.P.; Kalyanaraman, B.; et al. Prevention of diabetic nephropathy in Ins2+/- AkitaJ mice by the mitochondria-targeted therapy MitoQ. Biochem. J. 2010, 432, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiao, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Tang, D.; Wang, J.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, C.; et al. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorated tubular injury mediated by mitophagy in diabetic kidney disease via Nrf2/PINK1. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.S.; Flemming, N.B.; Gallo, L.A.; Fotheringham, A.K.; McCarthy, D.A.; Zhuang, A.; Tang, P.H.; Borg, D.J.; Shaw, H.; Harvie, B.; et al. Targeted mitochondrial therapy using MitoQ shows equivalent renoprotection to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition but no combined synergy in diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Yang, M.; Chen, X.; Xiong, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, L. DsbA-L deficiency exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction of tubular cells in diabetic kidney disease. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Xu, X.; Tang, C.; Gao, P.; Chen, X.; Xiong, X.; Yang, M.; Yang, S.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, S.; et al. Reactive oxygen species promote tubular injury in diabetic nephropathy: The role of the mitochondrial ros-txnip-nlrp3 biological axis. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Fujishima, H.; Chida, S.; Takahashi, K.; Qi, Z.; Kanetsuna, Y.; Breyer, M.D.; Harris, R.C.; Yamada, Y.; Takahashi, T. Reduction of renal superoxide dismutase in progressive diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peixoto, E.B.; Pessoa, B.S.; Biswas, S.K.; Lopes de Faria, J.B. Antioxidant SOD mimetic prevents NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative stress and renal damage in the early stage of experimental diabetes and hypertension. Am. J. Nephrol. 2009, 29, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaba, K.; Tojo, A.; Onozato, M.L.; Goto, A.; Fujita, T. Double-edged action of SOD mimetic in diabetic nephropathy. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2007, 49, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafikova, O.; Salah, E.M.; Tofovic, S.P. Renal and metabolic effects of tempol in obese ZSF1 rats—Distinct role for superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in diabetic renal injury. Metabolism 2008, 57, 1434–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mahdy, M.A.; Alzarie, Y.A.; Hemann, C.; Badary, O.A.; Nofal, S.; Zweier, J.L. The novel SOD mimetic GC4419 increases cancer cell killing with sensitization to ionizing radiation while protecting normal cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.M.; Lee, C.M.; Saunders, D.P.; Curtis, A.; Dunlap, N.; Nangia, C.; Lee, A.S.; Gordon, S.M.; Kovoor, P.; Arevalo-Araujo, R.; et al. Phase IIb, Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of GC4419 Versus Placebo to Reduce Severe Oral Mucositis Due to Concurrent Radiotherapy and Cisplatin for Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3256–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, A.R.; Khan, M.A.; Yeung, I.W.; van Dyk, J.; Hill, R.P. Partial volume rat lung irradiation: The protective/mitigating effects of Eukarion-189, a superoxide dismutase-catalase mimetic. Radiother. Oncol. 2006, 79, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Quintans, N.; Prieto, I.; Sanchez-Ramos, C.; Luque, A.; Arza, E.; Olmos, Y.; Monsalve, M. Regulation of endothelial dynamics by PGC-1alpha relies on ROS control of VEGF-A signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 93, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosakote, Y.M.; Komaravelli, N.; Mautemps, N.; Liu, T.; Garofalo, R.P.; Casola, A. Antioxidant mimetics modulate oxidative stress and cellular signaling in airway epithelial cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2012, 303, L991–L1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torbati, F.A.; Ramezani, M.; Dehghan, R.; Amiri, M.S.; Moghadam, A.T.; Shakour, N.; Elyasi, S.; Sahebkar, A.; Emami, S.A. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Features of Centella asiatica: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1308, 451–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, I.M.; Tzeng, T.F.; Liou, S.S.; Chang, C.J. Angelica acutiloba root attenuates insulin resistance induced by high-fructose diet in rats. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guan, Y.; Widlund, A.L.; Becker, L.B.; Baur, J.A.; Reilly, P.M.; Sims, C.A. Resveratrol ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction but increases the risk of hypoglycemia following hemorrhagic shock. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014, 77, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, L.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Grape seed procyanidin B2 ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibits apoptosis via the AMP-activated protein kinase-silent mating type information regulation 2 homologue 1-PPARgamma co-activator-1alpha axis in rat mesangial cells under high-dose glucosamine. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guerrero-Hue, M.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Vazquez-Carballo, C.; Palomino-Antolin, A.; Garcia-Caballero, C.; Opazo-Rios, L.; Morgado-Pascual, J.L.; Herencia, C.; Mas, S.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Protective Role of Nrf2 in Renal Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menini, S.; Iacobini, C.; Vitale, M.; Pugliese, G. The Inflammasome in Chronic Complications of Diabetes and Related Metabolic Disorders. Cells 2020, 9, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kataoka, S.; Kimura, A.; Mukai, Y. Azuki bean (Vigna angularis) extract reduces oxidative stress and stimulates autophagy in the kidneys of streptozotocin-induced early diabetic rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 94, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omara, E.A.; Nada, S.A.; Farrag, A.R.; Sharaf, W.M.; El-Toumy, S.A. Therapeutic effect of Acacia nilotica pods extract on streptozotocin induced diabetic nephropathy in rat. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navale, A.M.; Paranjape, A. Antidiabetic and renoprotective effect of Anogeissus acuminata leaf extract on experimentally induced diabetic nephropathy. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 29, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.J.; Lee, Y.A.; Yoo, H.H.; Yokozawa, T. Protective effects of broccoli (Brassica oleracea) against oxidative damage in vitro and in vivo. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2006, 52, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ALTamimi, J.Z.; AlFaris, N.A.; Al-Farga, A.M.; Alshammari, G.M.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Yahya, M.A. Curcumin reverses diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats by inhibition of PKCβ/p66Shc axis and activation of FOXO-3a. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 87, 108515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurukar, M.S.; Mahadevamma, S.; Chilkunda, N.D. Renoprotective effect of Coccinia indica fruits and leaves in experimentally induced diabetic rats. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boonphang, O.; Ontawong, A.; Pasachan, T.; Phatsara, M.; Duangjai, A.; Amornlerdpison, D.; Jinakote, M.; Srimaroeng, C. Antidiabetic and Renoprotective Effects of Coffea arabica Pulp Aqueous Extract through Preserving Organic Cation Transport System Mediated Oxidative Stress Pathway in Experimental Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Molecules 2021, 26, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.M.; Mahran, Y.F.; Ghanim, A.M.H. Ganoderma lucidum ameliorates the diabetic nephropathy via down-regulatory effect on TGFβ-1 and TLR-4/NFκB signalling pathways. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiju, T.M.; Rajesh, N.G.; Viswanathan, P. Renoprotective effect of aged garlic extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2013, 45, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.; Gurtu, S.; Chakravarthi, S.; Moorthy, M.; Palanisamy, U.D. Geraniin Protects High-Fat Diet-Induced Oxidative Stress in Sprague Dawley Rats. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hroob, A.M.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Alghonmeen, R.D.; Mahmoud, A.M. Ginger alleviates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis and protects rats against diabetic nephropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pang, X.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Xing, Y. Ginkgo Biloba Extract EGB761 Ameliorates the Extracellular Matrix Accumulation and Mesenchymal Transformation of Renal Tubules in Diabetic Kidney Disease by Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6657206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, J.; Huang, W.; Su, H.; Yuan, F.; Fang, K.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Zou, X.; et al. Berberine Protects Glomerular Podocytes via Inhibiting Drp1-Mediated Mitochondrial Fission and Dysfunction. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1698–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punaro, G.R.; Lima, D.Y.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Pugliero, S.; Mouro, M.G.; Rogero, M.M.; Higa, E.M.S. Cupuacu extract reduces nitrosative stress and modulates inflammatory mediators in the kidneys of experimental diabetes. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, T.D.; Brooks, N.L.; Oguntibeju, O.O. Leaf Extracts of Anchomanes difformis Ameliorated Kidney and Pancreatic Damage in Type 2 Diabetes. Plants 2021, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Dusabimana, T.; Kim, S.R.; Je, J.; Jeong, K.; Kang, M.C.; Cho, K.M.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.W. Supplementation of Abelmoschus manihot Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy and Hepatic Steatosis by Activating Autophagy in Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.C.; Lee, S.F.; Wang, C.J.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, W.C.; Lee, H.J. Aqueous Extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa Linnaeus Ameliorate Diabetic Nephropathy via Regulating Oxidative Status and Akt/Bad/14-3-3γ in an Experimental Animal Model. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 2011, 938126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Meng, Q.; Bian, H. A novel formula from mulberry leaf ameliorates diabetic nephropathy in rats via inhibiting the TGF-β1 pathway. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 3307–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.J.; Tzeng, T.F.; Hsu, J.C.; Kuo, S.H.; Chang, C.H.; Huang, S.Y.; Chang, F.Y.; Wu, M.C.; Liu, I.M. An Aqueous-Ethanol Extract of Liriope spicata var. prolifera Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy through Suppression of Renal Inflammation. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013, 2013, 201643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Yang, M.Y.; Hung, T.W.; Chang, Y.C.; Wang, C.J. Nelumbo nucifera leaves extract attenuate the pathological progression of diabetic nephropathy in high-fat diet-fed and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Mao, X. The anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects of Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt on high-glucose-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced diabetic renal damage in rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajavel, V.; Abdul Sattar, M.Z.; Abdulla, M.A.; Kassim, N.M.; Abdullah, N.A. Chronic Administration of Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Leaves Extract Attenuates Hyperglycaemic-Induced Oxidative Stress and Improves Renal Histopathology and Function in Experimental Diabetes. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 2012, 195367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, R.; Li, Y.; Mehmood, S.; Yan, C.; Huang, Y.; Cai, J.; Ji, J.; Pan, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y. Polysaccharides from Armillariella tabescens mycelia ameliorate renal damage in type 2 diabetic mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunasagara, S.; Hong, G.L.; Park, S.R.; Lee, N.H.; Jung, D.Y.; Kim, T.W.; Jung, J.Y. Korean red ginseng attenuates hyperglycemia-induced renal inflammation and fibrosis via accelerated autophagy and protects against diabetic kidney disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 254, 112693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgohain, M.P.; Chowdhury, L.; Ahmed, S.; Bolshette, N.; Devasani, K.; Das, T.J.; Mohapatra, A.; Lahkar, M. Renoprotective and antioxidative effects of methanolic Paederia foetida leaf extract on experimental diabetic nephropathy in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 198, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Long, T.; Yan, Y.; Qin, H.; Makinde, E.A.; Famurewa, A.C.; Jaisi, A.; Nie, Y.; et al. Tiliacora triandra extract and its major constituent attenuates diabetic kidney and testicular impairment by modulating redox imbalance and pro-inflammatory responses in rats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 1598–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, F.; Romecin, P.; Garcia-Guillen, A.I.; Wangesteen, R.; Vargas-Tendero, P.; Paredes, M.D.; Atucha, N.M.; Garcia-Estan, J. Flavonoids in Kidney Health and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guclu, A.; Yonguc, N.; Dodurga, Y.; Gundogdu, G.; Guclu, Z.; Yonguc, T.; Adiguzel, E.; Turkmen, K. The effects of grape seed on apoptosis-related gene expression and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Ren. Fail. 2015, 37, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, G.; Hu, Z.; Shi, W.; Chen, B.; Zou, P.; Li, X. Grape seed proanthocyanidins protect against streptozotocininduced diabetic nephropathy by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stressinduced apoptosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, B.Y.; Li, X.L.; Cheng, M.; Yu, F.; Lu, W.D.; Cai, Q.; Wang, J.F.; Zhou, R.H.; Gao, H.Q.; et al. Proteomic analysis of kidney and protective effects of grape seed procyanidin B2 in db/db mice indicate MFG-E8 as a key molecule in the development of diabetic nephropathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fujii, H.; Yokozawa, T.; Kim, Y.A.; Tohda, C.; Nonaka, G. Protective effect of grape seed polyphenols against high glucose-induced oxidative stress. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 2104–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Xiang, L.; Chen, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, L.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Deng, Y.; et al. Catalpol alleviates renal damage by improving lipid metabolism in diabetic db/db mice. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 1750–1761. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Cheon, J.; Yoon, H.; Jun, H.S. Cudrania tricuspidata Root Extract Prevents Methylglyoxal-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress via Regulation of the PKC-NOX4 Pathway in Human Kidney Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5511881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Lou, Y.; Bao, J.; Yu, J. Hyperoside ameliorates diabetic nephropathy induced by STZ via targeting the miR-499-5p/APC axis. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 146, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giribabu, N.; Karim, K.; Kilari, E.K.; Salleh, N. Phyllanthus niruri leaves aqueous extract improves kidney functions, ameliorates kidney oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis and apoptosis and enhances kidney cell proliferation in adult male rats with diabetes mellitus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 205, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, K.; Mishra, S.; Saha, M.; Mahapatra, S.; Saha, C.; Yenge, G.; Gaikwad, N.; Pal, R.; Oulkar, D.; Banerjee, K.; et al. Amelioration of diabetic nephropathy using pomegranate peel extract-stabilized gold nanoparticles: Assessment of NF-κB and Nrf2 signaling system. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 1753–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gomes, I.B.; Porto, M.L.; Santos, M.C.; Campagnaro, B.P.; Pereira, T.M.; Meyrelles, S.S.; Vasquez, E.C. Renoprotective, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic effects of oral low-dose quercetin in the C57BL/6J model of diabetic nephropathy. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Chi, Y.; Kang, Y.; Lu, H.; Niu, H.; Liu, W.; Li, Y. Resveratrol ameliorates podocyte damage in diabetic mice via SIRT1/PGC-1alpha mediated attenuation of mitochondrial oxidative stress. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5033–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, R.S.; Forster, M.J. Caloric restriction and the aging process: A critique. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 73, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sohal, R.S.; Weindruch, R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science 1996, 273, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diaz-Ruiz, A.; Di Francesco, A.; Carboneau, B.A.; Levan, S.R.; Pearson, K.J.; Price, N.L.; Ward, T.M.; Bernier, M.; de Cabo, R.; Mercken, E.M. Benefits of Caloric Restriction in Longevity and Chemical-Induced Tumorigenesis Are Transmitted Independent of NQO1. J. Gerontol. A 2019, 74, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Cai, G.Y.; Chen, X.M. Energy restriction in renal protection. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, K.L.; Clifton, P.M.; Keogh, J.B. The effect of intermittent energy restriction on weight loss and diabetes risk markers in women with a history of gestational diabetes: A 12-month randomized control trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrela, G.R.; Wasinski, F.; Batista, R.O.; Hiyane, M.I.; Felizardo, R.J.; Cunha, F.; de Almeida, D.C.; Malheiros, D.M.; Camara, N.O.; Barros, C.C.; et al. Caloric Restriction Is More Efficient than Physical Exercise to Protect from Cisplatin Nephrotoxicity via PPAR-Alpha Activation. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ning, Y.C.; Cai, G.Y.; Zhuo, L.; Gao, J.J.; Dong, D.; Cui, S.Y.; Shi, S.Z.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.F.; et al. Beneficial effects of short-term calorie restriction against cisplatin-induced acute renal injury in aged rats. Nephron Exp. Nephrol. 2013, 124, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.S.; Gades, M.D.; Wheeldon, C.M.; Borchers, A.T. Calorie restriction in obesity: Prevention of kidney disease in rodents. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 913S–917S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, G.; Krishan, P. Dietary restriction regimens for fighting kidney disease: Insights from rodent studies. Exp. Gerontol. 2019, 128, 110738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikoo, K.; Lodea, S.; Karpe, P.A.; Kumar, S. Calorie restriction mimicking effects of roflumilast prevents diabetic nephropathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pall, M.L.; Levine, S. Nrf2, a master regulator of detoxification and also antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and other cytoprotective mechanisms, is raised by health promoting factors. Sheng Li Xue Bao 2015, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Juszczak, F.; Caron, N.; Mathew, A.V.; Decleves, A.E. Critical Role for AMPK in Metabolic Disease-Induced Chronic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.L.; Hopp, K. Metabolic Reprogramming in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: Evidence and Therapeutic Potential. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kume, S.; Koya, D. Autophagy: A Novel Therapeutic Target for Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. J. 2015, 39, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, K. Mitochondrial hormesis and diabetic complications. Diabetes 2015, 64, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aydemir, N.; Pike, M.M.; Alsouqi, A.; Headley, S.A.E.; Tuttle, K.; Evans, E.E.; Milch, C.M.; Moody, K.A.; Germain, M.; Lipworth, L.; et al. Effects of diet and exercise on adipocytokine levels in patients with moderate to severe chronic kidney disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, S.K.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Fealy, C.E.; Scelsi, A.; Huang, H.; Rocco, M.; Kirwan, J.P. Exercise plus caloric restriction lowers soluble RAGE in adults with chronic kidney disease. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doshi, S.M.; Friedman, A.N. Diagnosis and Management of Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikizler, T.A.; Robinson-Cohen, C.; Ellis, C.; Headley, S.A.E.; Tuttle, K.; Wood, R.J.; Evans, E.E.; Milch, C.M.; Moody, K.A.; Germain, M.; et al. Metabolic Effects of Diet and Exercise in Patients with Moderate to Severe CKD: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Enomoto, H.; Tajima, S.; Izawa-Ishizawa, Y.; Kihira, Y.; Ishizawa, K.; Tomita, S.; Tsuchiya, K.; Tamaki, T. Dietary iron restriction inhibits progression of diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2013, 304, F1028–F1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Chuang, L.M. Early detection of diabetic kidney disease: Present limitations and future perspectives. World J. Diabetes 2016, 7, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarra-Gonzalez, I.; Cruz-Bautista, I.; Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Vela-Amieva, M.; Pallares-Mendez, R.; Ruiz de Santiago, Y.N.D.; Salas-Tapia, M.F.; Rosas-Flota, X.; Gonzalez-Acevedo, M.; Palacios-Penaloza, A.; et al. Optimization of kidney dysfunction prediction in diabetic kidney disease using targeted metabolomics. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, K.; Takeda, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Yokota, T.; Utsunomiya, K.; Nishimura, R. Targeting Redox Imbalance as an Approach for Diabetic Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Extracts/Components | Experimental Model | Major Mechanisms | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azuki bean extract | * STZ-rat | Autophagy stimulation | [183] |

| Acacia nilotica | STZ-rat | Antioxidant/anti-hyperglycemia | [184] |

| Anogeissus acuminate leaf | STZ-rat | Antioxidation | [185] |

| Broccoli | STZ-rat | Mitigating oxidative damage | [186] |

| Curcumin | STZ-rat | Inhibiting PKC beta | [187] |

| Coccinia indica | STZ-rat | Increased antioxidant enzymes | [188] |

| Coffea arabica pulp | HFD/STZ | Antioxidation upregulation | [189] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | STZ-rat | TGFβ-1, NFkB | [190] |

| Garlic extract | STZ-rat | Anti-glycation | [191] |

| Geraniin | * HFD | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [192] |

| Ginger extract | STZ-rat | Apoptosis attenuation | [193] |

| Ginkgo biloba EGB761 | HFD/STZ mouse | Mitigating ECM * accumulation | [194] |

| Berberine | db/db mouse | Mitochondrial fission | [195] |

| Cupuacu extract | STZ-rat | Mitigating nitrosation | [196] |

| Anchomanes difformis (leaf) | STZ-rat | Nrf2 activation | [197] |

| Abelmoschus manihot | HFD/STZ mouse | Autophagy activation | [198] |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa Linnaeus | STZ-rat | Akt regulating | [199] |

| Mulberry leaf | HFD/STZ rat | Inhibiting TGF-β1 | [200] |

| Liriope spicata var. prolifera | STZ-rat | Suppressing inflammation | [201] |

| Nelumbo nucifera leaf | HFD/STZ rat | Antioxidative | [202] |

| Coreopsis tinctoria nutt | High glucose/HFD/STZ | Anti-fibrotic | [203] |

| Oil palm | STZ-rat | Attenuating oxidative stress | [204] |

| Armillariella tabescens | STZ-mouse | Anti-inflammation | [205] |

| Red ginseng | STZ-rat | Autophagy acceleration | [206] |

| Paederia foetida leaf | Alloxan-rat | Antioxidative effects | [207] |

| Tiliacora triandra | HFD/STZ rat | Redox imbalance modulation | [208] |

| Flavonoids (review article) | Numerous models | Miscellaneous mechanisms | [209] |

| Grape seed | STZ-rat | Reduce apoptosis | [210] |

| Grape seed/proanthocyanidins | STZ-rat | Mitigating ER stress | [211] |

| Grape seed procyanidin B2 | db/db mouse | Targeting MFG-E8* | [212] |

| Grape seed polyphenols | Cell culture | Mitigating oxidative stress | [213] |

| Catlpol | db/db mouse | Improving lipid metabolism | [214] |

| Cudrania tricuspidata root | Human kidney cells | Preventing inflammation | [215] |

| Hyperoside | HFD/STZ mouse | Targeting miR-499-5p?APC | [216] |

| Phyllanthus niruri leaf | STZ/nicotinamide rat | Anti-fibrosis/apoptosis | [217] |

| Pomegranate peel extract | STZ-mouse | Nrf2 signaling pathway | [218] |

| Quercetin | STZ-mouse | Anti-apoptosis/oxidative stress | [219] |

| Resveratrol | STZ-mouse | Sirt1 activation | [220] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, L.-J. NADH/NAD+ Redox Imbalance and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11050730

Yan L-J. NADH/NAD+ Redox Imbalance and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Biomolecules. 2021; 11(5):730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11050730

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Liang-Jun. 2021. "NADH/NAD+ Redox Imbalance and Diabetic Kidney Disease" Biomolecules 11, no. 5: 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11050730

APA StyleYan, L. -J. (2021). NADH/NAD+ Redox Imbalance and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Biomolecules, 11(5), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11050730