The Biosynthesis, Signaling, and Neurological Functions of Bile Acids

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of BA

3. BA in the Brain

4. Signaling Induced by BA

4.1. Activation of Nuclear Receptors by BA

4.2. Activation of Cell-Surface Receptors by BA

4.3. Activation of Ion Channels by BA

5. Neurological Functions of BA

5.1. The Role of BA in the Brain

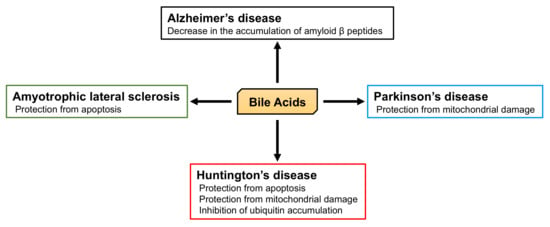

5.2. The Role of BA in Neurodegenerative Diseases

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomas, C.; Pellicciari, R.; Pruzanski, M.; Auwerx, J.; Schoonjans, K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, A.F.; Hagey, L.R.; Krasowski, M.D. Bile salts of vertebrates: Structural variation and possible evolutionary significance. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reschly, E.J.; Ai, N.; Ekins, S.; Welsh, W.J.; Hagey, L.R.; Hofmann, A.F.; Krasowski, M.D. Evolution of the bile salt nuclear receptor FXR in vertebrates. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 1577–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinaro, A.; Wahlstrom, A.; Marschall, H.U. Role of Bile Acids in Metabolic Control. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, N.; Goto, T.; Uchida, M.; Nishimura, K.; Ando, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Goto, J. Presence of protein-bound unconjugated bile acids in the cytoplasmic fraction of rat brain. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; Zhao, A.; Wang, X.; Xie, G.; Huang, F.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; et al. The Brain Metabolome of Male Rats across the Lifespan. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 24125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.Y. Bile acids: Regulation of synthesis. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1955–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.W. Fifty years of advances in bile acid synthesis and metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, S120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakheri, R.J.; Javitt, N.B. 27-Hydroxycholesterol, does it exist? On the nomenclature and stereochemistry of 26-hydroxylated sterols. Steroids 2012, 77, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aguiar Vallim, T.Q.; Tarling, E.J.; Edwards, P.A. Pleiotropic roles of bile acids in metabolism. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathena, S.P.; Mukherjee, S.; Olivera, M.; Alnouti, Y. The profile of bile acids and their sulfate metabolites in human urine and serum. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 942–943, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, T.; Sano, A.; Seto, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Nakagawa, Y.; Okuno, T.; Takino, T.; Hasegawa, T. Unusual trihydroxy bile acids in the urine of healthy humans. Clin. Chim. Acta 1986, 160, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Apte, U. Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling in Cholestasis, Inflammation, and Cancer. Adv. Pharmacol. 2015, 74, 263–302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trauner, M.; Boyer, J.L. Bile salt transporters: Molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 633–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikai, T.; Nakao, H.; Uchida, K. Deconjugation of bile acids by human intestinal bacteria implanted in germ-free rats. Lipids 1987, 22, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, M.; Gahan, C.G.; Hill, C. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lepercq, P.; Gerard, P.; Beguet, F.; Raibaud, P.; Grill, J.P.; Relano, P.; Cayuela, C.; Juste, C. Epimerization of chenodeoxycholic acid to ursodeoxycholic acid by Clostridium baratii isolated from human feces. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.P.; Dumas, M.E.; Wang, Y.; Legido-Quigley, C.; Yap, I.K.; Tang, H.; Zirah, S.; Murphy, G.M.; Cloarec, O.; Lindon, J.C.; et al. A top-down systems biology view of microbiome-mammalian metabolic interactions in a mouse model. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007, 3, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.D.; Csanaky, I.L.; Klaassen, C.D. Gender-divergent profile of bile acid homeostasis during aging of mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.Y. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, P.A.; Karpen, S.J. Intestinal transport and metabolism of bile acids. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oelkers, P.; Kirby, L.C.; Heubi, J.E.; Dawson, P.A. Primary bile acid malabsorption caused by mutations in the ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter gene (SLC10A2). J. Clin. Invest. 1997, 99, 1880–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, Y.; Eloranta, J.J.; Darimont, J.; Ismair, M.G.; Hiller, C.; Fried, M.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Vavricka, S.R. Regional distribution of solute carrier mRNA expression along the human intestinal tract. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shneider, B.L.; Dawson, P.A.; Christie, D.M.; Hardikar, W.; Wong, M.H.; Suchy, F.J. Cloning and molecular characterization of the ontogeny of a rat ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter. J. Clin. Invest. 1995, 95, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, D.M.; Dawson, P.A.; Thevananther, S.; Shneider, B.L. Comparative analysis of the ontogeny of a sodium-dependent bile acid transporter in rat kidney and ileum. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, G377–G385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. Role and Cytotoxicity of Amylin and Protection of Pancreatic Islet β-Cells from Amylin Cytotoxicity. Cells 2018, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wali, J.A.; Masters, S.L.; Thomas, H.E. Linking metabolic abnormalities to apoptotic pathways in Beta cells in type 2 diabetes. Cells 2013, 2, 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomi, T.; Santoro, N.; Caprio, S.; Cai, M.; Weng, J.; Groop, L. The many faces of diabetes: A disease with increasing heterogeneity. Lancet 2014, 383, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.E.; Cooper, M.E.; Del Prato, S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: Perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet 2014, 383, 1068–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.; Sonne, D.P.; Mikkelsen, K.H.; Gluud, L.L.; Vilsboll, T.; Knop, F.K. Bile acid sequestrants for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Aquino, C.J.; Cowan, D.J.; Anderson, D.L.; Ambroso, J.L.; Bishop, M.J.; Boros, E.E.; Chen, L.; Cunningham, A.; Dobbins, R.L.; et al. Discovery of a highly potent, nonabsorbable apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor (GSK2330672) for treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 5094–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.C.; Kramer, W.; Wilson, F.A. Identification of cytosolic and microsomal bile acid-binding proteins in rat ileal enterocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 14986–14995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christian, W.V.; Li, N.; Hinkle, P.M.; Ballatori, N. β-Subunit of the Ostalpha-Ostbeta organic solute transporter is required not only for heterodimerization and trafficking but also for function. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 21233–21243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballatori, N.; Christian, W.V.; Lee, J.Y.; Dawson, P.A.; Soroka, C.J.; Boyer, J.L.; Madejczyk, M.S.; Li, N. OSTalpha-OSTbeta: A major basolateral bile acid and steroid transporter in human intestinal, renal, and biliary epithelia. Hepatology 2005, 42, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, P.A.; Hubbert, M.; Haywood, J.; Craddock, A.L.; Zerangue, N.; Christian, W.V.; Ballatori, N. The heteromeric organic solute transporter alpha-beta, Ostalpha-Ostbeta, is an ileal basolateral bile acid transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 6960–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthanarayanan, M.; Ng, O.C.; Boyer, J.L.; Suchy, F.J. Characterization of cloned rat liver Na(+)-bile acid cotransporter using peptide and fusion protein antibodies. Am. J. Physiol 1994, 267, G637–G643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stieger, B.; Hagenbuch, B.; Landmann, L.; Hochli, M.; Schroeder, A.; Meier, P.J. In situ localization of the hepatocytic Na+/Taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide in rat liver. Gastroenterology 1994, 107, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenbuch, B.; Scharschmidt, B.F.; Meier, P.J. Effect of antisense oligonucleotides on the expression of hepatocellular bile acid and organic anion uptake systems in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biochem J. 1996, 316, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.K.; Bush, K.T.; Martovetsky, G.; Ahn, S.Y.; Liu, H.C.; Richard, E.; Bhatnagar, V.; Wu, W. The organic anion transporter (OAT) family: A systems biology perspective. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 83–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csanaky, I.L.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ogura, K.; Choudhuri, S.; Klaassen, C.D. Organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1b2 (Oatp1b2) is important for the hepatic uptake of unconjugated bile acids: Studies in Oatp1b2-null mice. Hepatology 2011, 53, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Sato, T.; Maekawa, M.; Goto, J.; Mano, N. Preference of Conjugated Bile Acids over Unconjugated Bile Acids as Substrates for OATP1B1 and OATP1B3. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Elliott, C.T.; McGuinness, B.; Passmore, P.; Kehoe, P.G.; Holscher, C.; McClean, P.L.; Graham, S.F.; Green, B.D. Metabolomic Profiling of Bile Acids in Clinical and Experimental Samples of Alzheimer’s Disease. Metabolites 2017, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.; Zhong, W.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Alteration of bile acid metabolism in the rat induced by chronic ethanol consumption. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3583–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benedetti, A.; Di Sario, A.; Marucci, L.; Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Schteingart, C.D.; Ton-Nu, H.T.; Hofmann, A.F. Carrier-mediated transport of conjugated bile acids across the basolateral membrane of biliary epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, G1416–G1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Pierre, M.V.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Hagenbuch, B.; Meier, P.J. Transport of bile acids in hepatic and non-hepatic tissues. J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 204, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choudhuri, S.; Cherrington, N.J.; Li, N.; Klaassen, C.D. Constitutive expression of various xenobiotic and endobiotic transporter mRNAs in the choroid plexus of rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.; Hartz, A.M.; Lucking, J.R.; Yang, X.; Pollack, G.M.; Miller, D.S. Coordinated nuclear receptor regulation of the efflux transporter, Mrp2, and the phase-II metabolizing enzyme, GSTpi, at the blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008, 28, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletti, R.H.; Novikoff, P.M.; Juvvadi, S.R.; Fritschy, J.M.; Meier, P.J.; Wolkoff, A.W. The choroid plexus epithelium is the site of the organic anion transport protein in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luissint, A.C.; Artus, C.; Glacial, F.; Ganeshamoorthy, K.; Couraud, P.O. Tight junctions at the blood brain barrier: Physiological architecture and disease-associated dysregulation. Fluids Barriers CNS 2012, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Occludin phosphorylation in regulation of epithelial tight junctions. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2009, 1165, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M.; McMillin, M.; Galindo, C.; Frampton, G.; Pae, H.Y.; DeMorrow, S. Bile acids permeabilize the blood brain barrier after bile duct ligation in rats via Rac1-dependent mechanisms. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanafi, N.I.; Mohamed, A.S.; Sheikh Abdul Kadir, S.H.; Othman, M.H.D. Overview of Bile Acids Signaling and Perspective on the Signal of Ursodeoxycholic Acid, the Most Hydrophilic Bile Acid, in the Heart. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Watanabe, S.; Tomaru, K.; Yamazaki, W.; Yoshizawa, K.; Ogawa, S.; Nagao, H.; Minato, K.; Maekawa, M.; Mano, N. Unconjugated bile acids in rat brain: Analytical method based on LC/ESI-MS/MS with chemical derivatization and estimation of their origin by comparison to serum levels. Steroids 2017, 125, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, F.; Hamilton, J.A.; Kamp, F.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Hamilton, J.A. Movement of fatty acids, fatty acid analogues, and bile acids across phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 11074–11086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.L.; Ray, D.R.; Moody, J.A.; Wells, J.D.; Van Lier, J.E. 24-hydroxycholesterol levels in human brain. J. Neurochem. 1972, 19, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meljon, A.; Theofilopoulos, S.; Shackleton, C.H.; Watson, G.L.; Javitt, N.B.; Knolker, H.J.; Saini, R.; Arenas, E.; Wang, Y.; Griffiths, W.J. Analysis of bioactive oxysterols in newborn mouse brain by LC/MS. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 2469–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutjohann, D.; Breuer, O.; Ahlborg, G.; Nennesmo, I.; Siden, A.; Diczfalusy, U.; Bjorkhem, I. Cholesterol homeostasis in human brain: Evidence for an age-dependent flux of 24S-hydroxycholesterol from the brain into the circulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 9799–9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, E.G.; Xie, C.; Kotti, T.; Turley, S.D.; Dietschy, J.M.; Russell, D.W. Knockout of the cholesterol 24-hydroxylase gene in mice reveals a brain-specific mechanism of cholesterol turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 22980–22988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, N.; Sato, Y.; Nagata, M.; Goto, T.; Goto, J. Bioconversion of 3beta-hydroxy-5-cholenoic acid into chenodeoxycholic acid by rat brain enzyme systems. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heverin, M.; Meaney, S.; Lutjohann, D.; Diczfalusy, U.; Wahren, J.; Bjorkhem, I. Crossing the barrier: Net flux of 27-hydroxycholesterol into the human brain. J. Lipid Res. 2005, 46, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, A.M.; Moreno-Ramos, O.A.; Haider, N.B. Role of Nuclear Receptors in Central Nervous System Development and Associated Diseases. J. Exp. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 93–121. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, C.A.; Paris, J.J.; Walf, A.A.; Rusconi, J.C. Effects and Mechanisms of 3alpha,5alpha, -THP on Emotion, Motivation, and Reward Functions Involving Pregnane Xenobiotic Receptor. Front. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Duboc, H.; Tache, Y.; Hofmann, A.F. The bile acid TGR5 membrane receptor: From basic research to clinical application. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Thathiah, A. Regulation of neuronal communication by G protein-coupled receptors. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 1607–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tayebati, S.K. Phospholipid and Lipid Derivatives as Potential Neuroprotective Compounds. Molecules 2018, 23, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, F.; Guerra, G.; Ammendola, R. Expression and signaling of formyl-peptide receptors in the brain. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, L.M.; Antel, J.P. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptors in the Central Nervous and Immune Systems. Curr. Drug Targets 2016, 17, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Q.; Ye, R.D. The Formyl Peptide Receptors: Diversity of Ligands and Mechanism for Recognition. Molecules 2017, 22, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Castillo, K.; Carrasquel-Ursulaez, W.; Sepulveda, R.V.; Gonzalez-Nilo, F.; Gonzalez, C.; Alvarez, O. Molecular Determinants of BK Channel Functional Diversity and Functioning. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 39–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemuth, D.; Assmann, M.; Grunder, S. The bile acid-sensitive ion channel (BASIC), the ignored cousin of ASICs and ENaC. Channels (Austin) 2014, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldez, T.; Afonso-Oramas, D.; Cruz-Muros, I.; Garcia-Marin, V.; Pagel, P.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, T.; Alvarez de la Rosa, D. Cloning and functional expression of a new epithelial sodium channel delta subunit isoform differentially expressed in neurons of the human and monkey telencephalon. J. Neurochem. 2007, 102, 1304–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberger, S.; Schild, L. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCI. structure, function, and pharmacology of acid-sensing ion channels and the epithelial Na+ channel. Pharmacol. Rev. 2015, 67, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contet, C.; Goulding, S.P.; Kuljis, D.A.; Barth, A.L. BK Channels in the Central Nervous System. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2016, 128, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Hollister, K.; Sowers, L.C.; Forman, B.M. Endogenous bile acids are ligands for the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR. Mol. Cell 1999, 3, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makishima, M.; Okamoto, A.Y.; Repa, J.J.; Tu, H.; Learned, R.M.; Luk, A.; Hull, M.V.; Lustig, K.D.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Shan, B. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science 1999, 284, 1362–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.J.; Blanchard, S.G.; Bledsoe, R.K.; Chandra, G.; Consler, T.G.; Kliewer, S.A.; Stimmel, J.B.; Willson, T.M.; Zavacki, A.M.; Moore, D.D.; et al. Bile acids: Natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science 1999, 284, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xie, C.; Lv, Y.; Li, J.; Krausz, K.W.; Shi, J.; Brocker, C.N.; Desai, D.; Amin, S.G.; Bisson, W.H.; et al. Intestine-selective farnesoid X receptor inhibition improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Li, Y.; Albert, I.; Hao, H.; Fabre, K.M.; Mitchell, J.B.; Patterson, A.D.; Gonzalez, F.J. Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, S.I.; Wahlstrom, A.; Felin, J.; Jantti, S.; Marschall, H.U.; Bamberg, K.; Angelin, B.; Hyotylainen, T.; Oresic, M.; Backhed, F. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.M.; Hart, S.N.; Kong, B.; Fang, J.; Zhong, X.B.; Guo, G.L. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.A.; Kast, H.R.; Anisfeld, A.M. BAREing it all: The adoption of LXR and FXR and their roles in lipid homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Seol, W.; Choi, H.S.; Moore, D.D. Isolation of proteins that interact specifically with the retinoid X receptor: Two novel orphan receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995, 9, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Laffitte, B.A.; Kast, H.R.; Nguyen, C.M.; Zavacki, A.M.; Moore, D.D.; Edwards, P.A. Identification of the DNA binding specificity and potential target genes for the farnesoid X-activated receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 10638–10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kast, H.R.; Goodwin, B.; Tarr, P.T.; Jones, S.A.; Anisfeld, A.M.; Stoltz, C.M.; Tontonoz, P.; Kliewer, S.; Willson, T.M.; Edwards, P.A. Regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (ABCC2) by the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X-activated receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 2908–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.M.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Nuclear Receptors, RXR, and the Big Bang. Cell 2014, 157, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ihunnah, C.A.; Jiang, M.; Xie, W. Nuclear receptor PXR, transcriptional circuits and metabolic relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willson, T.M.; Kliewer, S.A. PXR, CAR and drug metabolism. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, D.; Langer, T. The identification of ligand features essential for PXR activation by pharmacophore modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, S.A.; Goodwin, B.; Willson, T.M. The nuclear pregnane X receptor: A key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudinger, J.L.; Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Hawkins-Brown, D.; MacKenzie, K.I.; LaTour, A.; Liu, Y.; Klaassen, C.D.; Brown, K.K.; Reinhard, J.; et al. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3369–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staudinger, J.; Liu, Y.; Madan, A.; Habeebu, S.; Klaassen, C.D. Coordinate regulation of xenobiotic and bile acid homeostasis by pregnane X receptor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001, 29, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Barwick, J.L.; Simon, C.M.; Pierce, A.M.; Safe, S.; Blumberg, B.; Guzelian, P.S.; Evans, R.M. Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 3014–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y. Mechanism of rifampicin and pregnane X receptor inhibition of human cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase gene transcription. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005, 288, G74–G84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, S.; Ozalp, C.; Fang, S.; Xiang, L.; Kemper, J.K. Ligand-activated pregnane X receptor interferes with HNF-4 signaling by targeting a common coactivator PGC-1alpha. Functional implications in hepatic cholesterol and glucose metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 45139–45147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Meyer, U.A. Pregnane X receptor is a target of farnesoid X receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 19081–19091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuno, H.; Ikura, T.; Morizono, D.; Orita, I.; Yamada, S.; Shimizu, M.; Ito, N. Crystal structures of complexes of vitamin D receptor ligand-binding domain with lithocholic acid derivatives. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2206–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makishima, M.; Lu, T.T.; Xie, W.; Whitfield, G.K.; Domoto, H.; Evans, R.M.; Haussler, M.R.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Vitamin D receptor as an intestinal bile acid sensor. Science 2002, 296, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, T.C.; Li, X.; Sinal, C.J. Vitamin D receptor-dependent regulation of colon multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 gene expression by bile acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 23232–23242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavek, P.; Pospechova, K.; Svecova, L.; Syrova, Z.; Stejskalova, L.; Blazkova, J.; Dvorak, Z.; Blahos, J. Intestinal cell-specific vitamin D receptor (VDR)-mediated transcriptional regulation of CYP3A4 gene. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsubara, T.; Yoshinari, K.; Aoyama, K.; Sugawara, M.; Sekiya, Y.; Nagata, K.; Yamazoe, Y. Role of vitamin D receptor in the lithocholic acid-mediated CYP3A induction in vitro and in vivo. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 2058–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marino, S.; Carino, A.; Masullo, D.; Finamore, C.; Marchiano, S.; Cipriani, S.; Di Leva, F.S.; Catalanotti, B.; Novellino, E.; Limongelli, V.; et al. Hyodeoxycholic acid derivatives as liver X receptor alpha and G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor agonists. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Hiipakka, R.A.; Liao, S. Selective activation of liver X receptor alpha by 6alpha-hydroxy bile acids and analogs. Steroids 2000, 65, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, D.J.; Turley, S.D.; Ma, W.; Janowski, B.A.; Lobaccaro, J.M.; Hammer, R.E.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell 1998, 93, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Schuster, G.; Parini, P.; Feltkamp, D.; Diczfalusy, U.; Rudling, M.; Angelin, B.; Bjorkhem, I.; Pettersson, S.; Gustafsson, J.A. Hepatic cholesterol metabolism and resistance to dietary cholesterol in LXRbeta-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 107, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pandak, W.M.; Hylemon, P.B. LXR alpha is the dominant regulator of CYP7A1 transcription. Biochem. Biophys Res. Commun. 2002, 293, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadmiel, M.; Cidlowski, J.A. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMillin, M.; Frampton, G.; Quinn, M.; Divan, A.; Grant, S.; Patel, N.; Newell-Rogers, K.; DeMorrow, S. Suppression of the HPA Axis During Cholestasis Can Be Attributed to Hypothalamic Bile Acid Signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T.; Ouchida, R.; Yoshikawa, N.; Okamoto, K.; Makino, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Morimoto, C.; Makino, I.; Tanaka, H. Functional modulation of the glucocorticoid receptor and suppression of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription by ursodeoxycholic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 47371–47378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Wang, C.; Lu, X.; Tong, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, W. Identification of functional farnesoid X receptors in brain neurons. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 3233–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hagedorn, C.H.; Wang, L. Role of nuclear receptor SHP in metabolism and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maruyama, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Tamai, Y.; Okada, H.; Sugiyama, E.; Nakamura, T.; Itadani, H.; Tanaka, K. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 298, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamata, Y.; Fujii, R.; Hosoya, M.; Harada, M.; Yoshida, H.; Miwa, M.; Fukusumi, S.; Habata, Y.; Itoh, T.; Shintani, Y.; et al. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 9435–9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Macchiarulo, A.; Thomas, C.; Gioiello, A.; Une, M.; Hofmann, A.F.; Saladin, R.; Schoonjans, K.; Pellicciari, R.; Auwerx, J. Novel potent and selective bile acid derivatives as TGR5 agonists: Biological screening, structure-activity relationships, and molecular modeling studies. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen, W.D.; Wang, Y.D. TGR5, Not Only a Metabolic Regulator. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancedo, J.M. Biological roles of cAMP: Variations on a theme in the different kingdoms of life. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2013, 88, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.P.; Asgharpour, A.; Mirshahi, F.; Park, S.H.; Liu, S.; Imai, Y.; Nadler, J.L.; Grider, J.R.; Murthy, K.S.; Sanyal, A.J. Activation of Transmembrane Bile Acid Receptor TGR5 Modulates Pancreatic Islet alpha Cells to Promote Glucose Homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 6626–6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.C.; Breckler, M.; Berthouze, M.; Lezoualc’h, F. Role of Epac in brain and heart. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012, 40, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscioni, S.S.; Elzinga, C.R.; Schmidt, M. Epac: Effectors and biological functions. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2008, 377, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaux, W.G., 3rd; Cheng, X. Intracellular cAMP Sensor EPAC: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics Development. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 919–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Behar, J.; Wands, J.; Resnick, M.; Wang, L.J.; DeLellis, R.A.; Lambeth, D.; Souza, R.F.; Spechler, S.J.; Cao, W. Role of a novel bile acid receptor TGR5 in the development of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut 2010, 59, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyuk, A.I.; Huang, B.Q.; Radtke, B.N.; Gajdos, G.B.; Splinter, P.L.; Masyuk, T.V.; Gradilone, S.A.; LaRusso, N.F. Ciliary subcellular localization of TGR5 determines the cholangiocyte functional response to bile acid signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G1013–G1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Tian, W.; Hong, J.; Li, D.; Tavares, R.; Noble, L.; Moss, S.F.; Resnick, M.B. Expression of bile acid receptor TGR5 in gastric adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G322–G327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Liu, H.; Boehme, S.; Xie, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Gonzalez, F.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Farnesoid X receptor induces Takeda G-protein receptor 5 cross-talk to regulate bile acid synthesis and hepatic metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11055–11069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahajan-Thakur, S.; Bien-Moller, S.; Marx, S.; Schroeder, H.; Rauch, B.H. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) signaling in glioblastoma multiforme-A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, E.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Takabe, K.; Nagahashi, M.; Pandak, W.M.; Dent, P.; Spiegel, S.; Shi, R.; et al. Conjugated bile acids activate the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 in primary rodent hepatocytes. Hepatology 2012, 55, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillin, M.; Frampton, G.; Grant, S.; Khan, S.; Diocares, J.; Petrescu, A.; Wyatt, A.; Kain, J.; Jefferson, B.; DeMorrow, S. Bile Acid-Mediated Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 2 Signaling Promotes Neuroinflammation during Hepatic Encephalopathy in Mice. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Gong, Z.; Du, X.; Tian, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Xu, C.; Chen, Y.; Cai, W.; Wu, J. Deoxycholic Acid-Mediated Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 2 Signaling Exacerbates DSS-Induced Colitis through Promoting Cathepsin B Release. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 2481418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, A.C.; Kobilka, B.K.; Gautam, D.; Sexton, P.M.; Christopoulos, A.; Wess, J. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: Novel opportunities for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.; Diakonov, I.; Arunthavarajah, D.; Swift, T.; Goodwin, M.; McIlvride, S.; Nikolova, V.; Williamson, C.; Gorelik, J. Bile acids and their respective conjugates elicit different responses in neonatal cardiomyocytes: Role of Gi protein, muscarinic receptors and TGR5. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh Abdul Kadir, S.H.; Miragoli, M.; Abu-Hayyeh, S.; Moshkov, A.V.; Xie, Q.; Keitel, V.; Nikolaev, V.O.; Williamson, C.; Gorelik, J. Bile acid-induced arrhythmia is mediated by muscarinic M2 receptors in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhana, L.; Nangia-Makker, P.; Arbit, E.; Shango, K.; Sarkar, S.; Mahmud, H.; Hadden, T.; Yu, Y.; Majumdar, A.P. Bile acid: A potential inducer of colon cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S.; Yamada, M.; Wess, J.; Kennedy, R.H.; Raufman, J.P. Deoxycholyltaurine-induced vasodilation of rodent aorta is nitric oxide- and muscarinic M(3) receptor-dependent. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 517, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Quinn, M.T. Antagonism of human formyl peptide receptor 1 with natural compounds and their synthetic derivatives. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 37, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, D.; Shen, W.; Dong, H.F.; Wang, J.M.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Howard, M.Z. Characterization of chenodeoxycholic acid as an endogenous antagonist of the G-coupled formyl peptide receptors. Inflamm. Res. 2000, 49, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mellon, R.D.; Yang, L.; Dong, H.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Howard, O.M. Regulatory effects of deoxycholic acid, a component of the anti-inflammatory traditional Chinese medicine Niuhuang, on human leukocyte response to chemoattractants. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 63, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzig, P.; Wirtz, M.; Wiemuth, D. Comparative electrophysiological analysis of the bile acid-sensitive ion channel (BASIC) from different species suggests similar physiological functions. Pflugers Arch. 2019, 471, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyaskin, A.V.; Diakov, A.; Korbmacher, C.; Haerteis, S. Activation of the Human Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) by Bile Acids Involves the Degenerin Site. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 19835–19847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dopico, A.M.; Walsh, J.V., Jr.; Singer, J.J. Natural bile acids and synthetic analogues modulate large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel activity in smooth muscle cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2002, 119, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukiya, A.N.; Singh, A.K.; Parrill, A.L.; Dopico, A.M. The steroid interaction site in transmembrane domain 2 of the large conductance, voltage- and calcium-gated potassium (BK) channel accessory beta1 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20207–20212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Andersson, K.E.; Buccafusco, J.J.; Chapple, C.; de Groat, W.C.; Fryer, A.D.; Kay, G.; Laties, A.; Nathanson, N.M.; Pasricha, P.J.; et al. Muscarinic receptors: Their distribution and function in body systems, and the implications for treating overactive bladder. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. D-Amino Acids in the Nervous and Endocrine Systems. Scientifica (Cairo) 2016, 2016, 6494621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca Balderas, P. Flux-Independent NMDAR Signaling: Molecular Mediators, Cellular Functions, and Complexities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. NMDA Receptor Function During Senescence: Implication on Cognitive Performance. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, S.S. Structure-Dependent Activity of Natural GABA(A) Receptor Modulators. Molecules 2018, 23, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubring, S.R.; Fleischer, W.; Lin, J.S.; Haas, H.L.; Sergeeva, O.A. The bile steroid chenodeoxycholate is a potent antagonist at NMDA and GABA(A) receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 506, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, A.; Bonnavion, P.; Wilson, M.H.; Mickelsen, L.E.; Bloit, J.; de Lecea, L.; Jackson, A.C. Hypothalamic Tuberomammillary Nucleus Neurons: Electrophysiological Diversity and Essential Role in Arousal Stability. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 9574–9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.F.; Fan, K.; Wang, C.; Xie, P.; Hou, M.; Xin, L.; Cui, G.F.; Wang, L.X.; Shao, Y.F.; Hou, Y.P. Inactivation of the Tuberomammillary Nucleus by GABAA Receptor Agonist Promotes Slow Wave Sleep in Freely Moving Rats and Histamine-Treated Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 2314–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovsky, Y.; Schubring, S.R.; Yao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; May, A.; Haas, H.L.; Lin, J.S.; Sergeeva, O.A. Waking action of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) involves histamine and GABAA receptor block. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.; Ribeiro, F.F.; Xapelli, S.; Genebra, T.; Ribeiro, M.F.; Sebastiao, A.M.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Sola, S. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid Enhances Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Neural Stem Cell Pool, and Early Neurogenesis in Adult Rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 3725–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.M.; Ming, G.L.; Song, H. Adult Mammalian Neural Stem Cells and Neurogenesis: Five Decades Later. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holtzman, D.M.; Morris, J.C.; Goate, A.M. Alzheimer’s disease: The challenge of the second century. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 77sr71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.L.; Vassar, R. The Basic Biology of BACE1: A Key Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Genom. 2007, 8, 509–530. [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, T. Molecular mechanism of intramembrane proteolysis by gamma-secretase. J. Biochem. 2014, 156, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, L.; Yang, G.; Yan, C.; Zhou, R.; Zhou, X.; Xie, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, X.; et al. Structural basis of human gamma-secretase assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6003–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Yu, W.H.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Mohan, P.S.; Peterhoff, C.M.; Wolfe, D.M.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Massey, A.C.; Sovak, G.; et al. Lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy require presenilin 1 and are disrupted by Alzheimer-related PS1 mutations. Cell 2010, 141, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.F.; Amaral, J.D.; Lo, A.C.; Fonseca, M.B.; Viana, R.J.; Callaerts-Vegh, Z.; D’Hooge, R.; Rodrigues, C.M. TUDCA, a bile acid, attenuates amyloid precursor protein processing and amyloid-beta deposition in APP/PS1 mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 45, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.C.; Callaerts-Vegh, Z.; Nunes, A.F.; Rodrigues, C.M.; D’Hooge, R. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) supplementation prevents cognitive impairment and amyloid deposition in APP/PS1 mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 50, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marksteiner, J.; Blasko, I.; Kemmler, G.; Koal, T.; Humpel, C. Bile acid quantification of 20 plasma metabolites identifies lithocholic acid as a putative biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease. Metabolomics 2018, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MahmoudianDehkordi, S.; Arnold, M.; Nho, K.; Ahmad, S.; Jia, W.; Xie, G.; Louie, G.; Kueider-Paisley, A.; Moseley, M.A.; Thompson, J.W.; et al. Altered bile acid profile associates with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease-An emerging role for gut microbiome. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area-Gomez, E.; de Groof, A.; Bonilla, E.; Montesinos, J.; Tanji, K.; Boldogh, I.; Pon, L.; Schon, E.A. A key role for MAM in mediating mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Xie, F.; Su, B.; Wang, X. Abnormalities of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel) 2017, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. Intra- and Intercellular Quality Control Mechanisms of Mitochondria. Cells 2018, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.M.; Barnes, K.; Clemmens, H.; Al-Rafiah, A.R.; Al-Ofi, E.A.; Leech, V.; Bandmann, O.; Shaw, P.J.; Blackburn, D.J.; Ferraiuolo, L.; et al. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Improves Mitochondrial Function and Redistributes Drp1 in Fibroblasts from Patients with Either Sporadic or Familial Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mol. Biol 2018, 430, 3942–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J. Parkinson’s disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. The Function of Autophagy in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26797–26812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gladkova, C.; Maslen, S.L.; Skehel, J.M.; Komander, D. Mechanism of parkin activation by PINK1. Nature 2018, 559, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J. Genetic analysis of pathways to Parkinson disease. Neuron 2010, 68, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickrell, A.M.; Youle, R.J. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 2015, 85, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.M.; Ordureau, A.; Paulo, J.A.; Rinehart, J.; Harper, J.W. The PINK1-PARKIN Mitochondrial Ubiquitylation Pathway Drives a Program of OPTN/NDP52 Recruitment and TBK1 Activation to Promote Mitophagy. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarou, M.; Sliter, D.A.; Kane, L.A.; Sarraf, S.A.; Wang, C.; Burman, J.L.; Sideris, D.P.; Fogel, A.I.; Youle, R.J. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature 2015, 524, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez, T.N.; Greenamyre, J.T. Toxin models of mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, N.M.C.; Theurey, P.; Adam-Vizi, V.; Bazan, N.G.; Bernardi, P.; Bolanos, J.P.; Culmsee, C.; Dawson, V.L.; Deshmukh, M.; Duchen, M.R.; et al. Guidelines on experimental methods to assess mitochondrial dysfunction in cellular models of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 542–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Caldas, M.; Carvalho, A.N.; Rodrigues, E.; Henderson, C.J.; Wolf, C.R.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Gama, M.J. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid prevents MPTP-induced dopaminergic cell death in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, S.; Fonseca, I.; Nunes, M.J.; Rosa, A.; Lemos, L.; Rodrigues, E.; Carvalho, A.N.; Outeiro, T.F.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gama, M.J.; et al. Nrf2 activation by tauroursodeoxycholic acid in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 295, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.I.; Duarte-Silva, S.; Silva-Fernandes, A.; Nunes, M.J.; Carvalho, A.N.; Rodrigues, E.; Gama, M.J.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Maciel, P.; Castro-Caldas, M. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid Improves Motor Symptoms in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 9139–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.I.; Fonseca, I.; Nunes, M.J.; Moreira, S.; Rodrigues, E.; Carvalho, A.N.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Gama, M.J.; Castro-Caldas, M. Novel insights into the antioxidant role of tauroursodeoxycholic acid in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 2171–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, N.F.; Safar, M.M.; Salem, H.A. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Ameliorates Apoptotic Cascade in the Rotenone Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Modulation of Mitochondrial Perturbations. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayalu, P.; Albin, R.L. Huntington disease: Pathogenesis and treatment. Neurol. Clin. 2015, 33, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell 1993, 72, 971–983. [Google Scholar]

- Tunez, I.; Tasset, I.; Perez-De La Cruz, V.; Santamaria, A. 3-Nitropropionic acid as a tool to study the mechanisms involved in Huntington’s disease: Past, present and future. Molecules 2010, 15, 878–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Popovic, N.; Brundin, P. The use of the R6 transgenic mouse models of Huntington’s disease in attempts to develop novel therapeutic strategies. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, C.D.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Eich, T.; Linehan-Stieers, C.; Abt, A.; Kren, B.T.; Steer, C.J.; Low, W.C. A bile acid protects against motor and cognitive deficits and reduces striatal degeneration in the 3-nitropropionic acid model of Huntington’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 171, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiarini, L.; Sathasivam, K.; Seller, M.; Cozens, B.; Harper, A.; Hetherington, C.; Lawton, M.; Trottier, Y.; Lehrach, H.; Davies, S.W.; et al. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell 1996, 87, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, C.D.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Eich, T.; Chhabra, M.S.; Steer, C.J.; Low, W.C. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid, a bile acid, is neuroprotective in a transgenic animal model of Huntington’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10671–10676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenemann, K.; Jansen, A.H.P.; van Riel, L.; Merkx, R.; Mulder, M.P.C.; An, H.; Statsyuk, A.; Kirstein, J.; Ovaa, H.; Reits, E.A. Dynamic recruitment of ubiquitin to mutant huntingtin inclusion bodies. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, R.; Navarro, X. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Current perspectives from basic research to the clinic. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015, 133, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, A.E.; Chio, A.; Traynor, B.J. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgio, F.; Maduro, C.; Fisher, E.M.C.; Acevedo-Arozena, A. Transgenic and physiological mouse models give insights into different aspects of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dis. Model. Mech 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyderman, H.; Hutson, P.G.; Matusica, D.; Rogers, M.L.; Rush, R.A. The human G93A-superoxide dismutase-1 mutation, mitochondrial glutathione and apoptotic cell death. Neurochem. Res. 2009, 34, 1847–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, A.R.; Cunha, C.; Gomes, C.; Schmucki, N.; Barbosa, M.; Brites, D. Glycoursodeoxycholic acid reduces matrix metalloproteinase-9 and caspase-9 activation in a cellular model of superoxide dismutase-1 neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 51, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, A.E.; Lalli, S.; Monsurro, M.R.; Sagnelli, A.; Taiello, A.C.; Reggiori, B.; La Bella, V.; Tedeschi, G.; Albanese, A. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarenac, T.M.; Mikov, M. Bile Acid Synthesis: From Nature to the Chemical Modification and Synthesis and Their Applications as Drugs and Nutrients. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, G.J.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Aranha, M.M.; Hilbert, S.J.; Davey, C.; Kelkar, P.; Low, W.C.; Steer, C.J. Safety, tolerability, and cerebrospinal fluid penetration of ursodeoxycholic Acid in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2010, 33, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiriyama, Y.; Nochi, H. The Biosynthesis, Signaling, and Neurological Functions of Bile Acids. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9060232

Kiriyama Y, Nochi H. The Biosynthesis, Signaling, and Neurological Functions of Bile Acids. Biomolecules. 2019; 9(6):232. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9060232

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiriyama, Yoshimitsu, and Hiromi Nochi. 2019. "The Biosynthesis, Signaling, and Neurological Functions of Bile Acids" Biomolecules 9, no. 6: 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9060232

APA StyleKiriyama, Y., & Nochi, H. (2019). The Biosynthesis, Signaling, and Neurological Functions of Bile Acids. Biomolecules, 9(6), 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9060232