Participation, for Whom? The Potential of Gamified Participatory Artefacts in Uncovering Power Relations within Urban Renewal Projects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Political Role of Gamified Participatory Processes

2. Literature Review

2.1. Participatory Mapping via Gamified Participatory Artefacts versus Knowledge, Action, and Consciousness

2.2. Knowledge

- when is knowledge made visible and how can it be redistributed?

2.3. Action

- how can gamified participatory artefacts make power relations visible?

- how can gamified participatory artefacts involve the voices of ‘others’ in the participatory process?

2.4. Consciousness

- when are power relations challenged?

3. Case Study

3.1. Genk: A City in Transition

3.2. The Urban Renewal Process of Vennestraat

3.3. Urban Space

3.4. Subsidies

3.5. Markets and Festivals

3.6. Call for Projects

3.7. The Outcome

4. Methodology

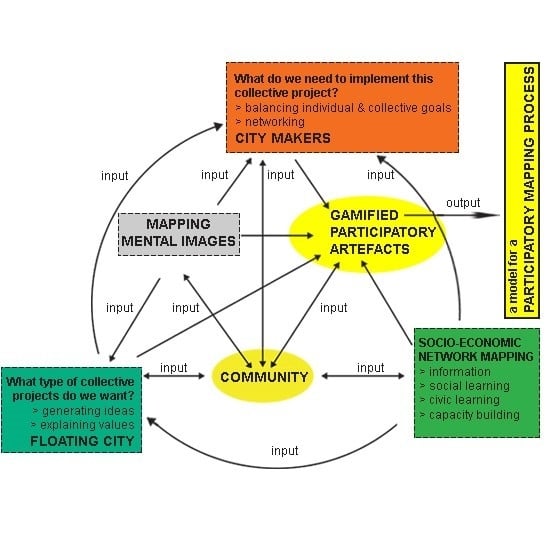

4.1. A Participatory Mapping Process

4.1.1. Socio-Economic Network Mapping

4.1.2. Knowledge

4.1.3. Action

4.1.4. Consciousness

4.2. Mental Images

4.2.1. Knowledge

4.2.2. Action

4.2.3. Consciousness

4.3. Scenario Games

4.3.1. Knowledge

4.3.2. Action

4.3.3. Consciousness

5. Research Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaventa, J.; Cornwall, A. Challenging the Boundaries of the Possible: Participation, Knowledge and Power. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harviainen, J.T.; Hassan, L. Governmental Service Gamification. Int. J. Innov. Digit. Econ. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, C. Serious Games; Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, R. Metropolis: The Urban Systems Game; Gamed Simulations, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O.; Kostov, G. City makers: Insights on the development of a serious game to support collective reflection and knowledge transfer in participatory processes. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2017, 6, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Whatmore, S.J. Mapping knowledge controversies: Science, democracy and the redistribution of expertise. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devisch, O.; Poplin, A.; Sofronie, S. The gamification of civic participation: Two experiments in improving the skills of citizens to reflect collectively on spatial issues. J. Urban Technol. 2016, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.L. From margins to center? The development and purpose of participatory research. Am. Sociol. 1992, 23, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, A. Genres of power: Literacy education and the production of capital. In Critical Literacy, Schooling, and Social Justice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.C.; Van Kerkhoff, L.; Lebel, L.; Gallopin, G. Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4570–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fals-Borda, O.; Rahman, M.A. Action and Knowledge: Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory Action-Research; Apex Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, J. Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Parlett, D. The Oxford History of Board Games; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Suits, B. The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia, 4th ed.; Broadview Press: Toronto, Canada, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, A.I.A.; Felicia, P. Gameplay engagement and learning in game-based learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 740–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, N. Encouraging engagement in game-based learning. Int. J. Game-Based Learn. 2011, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahlgren, P. Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, B.; Ferri, G.; de Lange, M.; Millenaar, K. Games as strong concepts for city-making. In Playable Cities, Gaming Media and Social Effects; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devisch, O.; Gugerell, K.; Diephuis, J.; Constantinescu, T.; Ampatzidou, C.; Jauschneg, M. Mini is beautiful: Playing serious mini-games to facilitate collective learning on complex urban processes. Interact. Des. Archit. 2018, 35, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, I. The gaming of policy and the politics of gaming: A review. Simul. Gaming 2009, 40, 825–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, A. Playful public participation in urban planning: A case study for online serious games. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetser, P. An Emergent Approach to Game Design: Development and Play. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.-M.; Chen, K.-M.; Huang, Y.-J. Emotional reactions of different interface formats: Comparing digital and traditional board games. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brian, G.; de Kort, Y.; Ijsselsteijn, W. Influence of social setting on player experience in digital games. In CHI’08 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Kientz, J.A., Ed.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Back matter—Whose Reality Counts? In Whose Reality Counts?: Putting the First Last; Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd: London, UK, 1997; pp. 238–298. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S.; Kapoor, D. Re-politicizing participatory action research: Unmasking neoliberalism and the illusions of participation. Educ. Action Res. 2016, 24, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selener, D. Participatory Action Research and Social Change, 2nd ed.; The Cornell Participatory Action Research Network, Cornell University: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Action research and minority problems (1946). In Resolving Social Conflicts: Selected Papers on Group Dynamics; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1948; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Flexible accumulation through urbanisation: Some reactions on ‘post-modernism’ in the American city. Antipode 1987, 19, 260–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.L. Breaking the monopoly of action knowledge: Research methods, participation and development. In Participatory Research: Revisiting the Roots; Tandon, R., Ed.; Mosaic Books: New Delhi, India, 2002; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Shukaitis, S.; Graeber, D. Introduction. In Constituent Imagination: Militant Investigations, Collective Theoritization; Shukaitis, S., Graeber, D., Eds.; AK Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2007; pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.L. Participatory research, popular knowledge, and power: A personal reflection. Convergence 1981, 14, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lardier, D.T. Substance use among urban youth of color: Exploring the role of community-based predictors, ethnic identity, and intrapersonal psychological empowerment. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Visie stad Genk 2014–2019. Available online: www.genk.be/meerjarenplanning-2014-2019 (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- David—Vennestraat Street manager, One on one interview series conducted by the researcher in Vennestraat street, Genk, on 16 September 2018.

- Jacobs, J. The Economy of Cities; Random House, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Fass, J. Everybody Needs Somebody: Physical Social Networks & Visualisation; CX Program Royal College of Art Kensington Gore London, UK Arts and Humanities Research Council: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, W.; Otto, T.; Smith, R.C. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoli, A. Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O. Portraits of work: Mapping emerging coworking dynamics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 21, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, J.; Amnå, E. Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Hum. Aff. 2012, 22, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McRobbie, A. Clubs to companies: Notes on the decline of political culture in speeded up creative worlds. Cult. Stud. 2002, 16, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conventz, S.; Derudder, B.; Thierstein, A.; Witlox, F. Hub Cities in the Knowledge Economy: Seaports, Airports, Brainports; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sulsters, W. Mental Mapping: Viewing the Urban. Landscapes of the Mind. Available online: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:fc71de16b4854888b6fea9d2771d9e4a (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Da Mota Neto, J.C. Toward a decolonial pedagogy in Latin America: Convergences between popular education and participatory action research. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2018, 26, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh, J.; Bush, P.L.; Salsberg, J.; Macaulay, A.C.; Greenhalgh, T.; Wong, G.; Cargo, M.; Green, L.W.; Herbert, C.P.; Pluye, P. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burnside-Lawry, J.; Carvalho, L. A stakeholder approach to building community resilience: Awareness to implementation. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2016, 7, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shardlow, S.; Aldgate, J.; Gibson, A.; Brearley, J.; Daniel, B.; Statham, D.; Doel, M. Handbook for Practice Learning in Social Work and Social Care: Knowledge and Theory; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Floating City | City Makers | |

|---|---|---|

| Design goals | What collective project do we want? What do we want to do together? • generating ideas • explaining values | What do we need to implement this collective project? • balancing individual and collective goals • networking |

| Type of game | video game | card-based game |

| Who is the game for? | Mixed groups and/or specific groups Age: 16–60+ Education: mixed groups and/or specific groups (low educated–higher education) Gaming experience: low to none | Mixed groups and/or specific groups Age: 16–60+ Education: mixed groups and/or specific groups (low educated–higher education) Gaming experience: low to none |

| Input | Player brainstorms | Floating City |

| Narrative | • foster positive thinking, commonality between participants • provides a motivating structure for discussions that involves all participants in expressing shared values | • define the steps that you need to implement the action • define your own project • define for yourself which achievements you need to succeed in this project |

| Expected dynamics | • participants interact, define common values • discuss issues, compare differences in perspectives • upon issues, react to behaviour that does not comply with their norms or values | • participants collaborate over particular assignments, sabotaging common ‘enemy’, to change perspectives (e.g., no longer see something as a problem but as a challenge) • participants evaluate one’s action’s, role, assess progress |

| Expected experiences | • collective reflection • collective efficacy | • increased trust • informing • collective learning |

| Mechanics | collaboration | • collaboration • competition |

| Output | What are (collective) ambitions? • shared norms • shared success criteria • a collective project (program) | What are the chosen projects to reach the (collective) ambitions/to address a common challenge? • alliances of players, linked to the projects/resources • strategies/steps/actors required to implement the given project • proposals for (extra) actors, individual projects and collective projects |

| Debriefing | • summary and comments from people on the different ideas • informing on what happens with the collection next (follow up) | ask players to reflect on alternative projects |

| Setting of the game | living lab setting, workshopslong participatory processes | living lab setting, workshopslong participatory processes |

| Expected duration of the game | 1 h–1 h 30′ | 30’–40’ |

| Socio-Economic Network Mapping | Mental Images | Scenario Games | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | • economic networks • social networks • proprietors’ clusters • spatial division on the street • ethnic clusters | • local landmarks • nostalgia over specific shops/spaces (e.g., the Cinema) • valuation of the street | • reveal individual wishes/needs • collective reflection over shared projects on the street • identify problems/tensions |

| Action | • clear goals • attention completely absorbed in the activity • high intensity of interaction • visualize abstract notions/concepts | • clear goals • articulate thoughts and lived experiences in an expressive language | • the activity has clear goals • provide high intensity and feedback • sensory and cognitive curiosity for participants • provide a continuous sense of challenge that is neither too difficult as to create frustration nor too easy as to be boring |

| Consciousness | • reflect over existing links • shape psychological and conceptual boundaries • challenge existing power relations | • individual/collective carriers of urban identity • understand the general functioning of the street | • understand the driving forces of the participatory process • identify all actors involved in the decision-making process • understand priorities |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iulia Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O.; Huybrechts, L. Participation, for Whom? The Potential of Gamified Participatory Artefacts in Uncovering Power Relations within Urban Renewal Projects. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050319

Iulia Constantinescu T, Devisch O, Huybrechts L. Participation, for Whom? The Potential of Gamified Participatory Artefacts in Uncovering Power Relations within Urban Renewal Projects. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2020; 9(5):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050319

Chicago/Turabian StyleIulia Constantinescu, Teodora, Oswald Devisch, and Liesbeth Huybrechts. 2020. "Participation, for Whom? The Potential of Gamified Participatory Artefacts in Uncovering Power Relations within Urban Renewal Projects" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 9, no. 5: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050319

APA StyleIulia Constantinescu, T., Devisch, O., & Huybrechts, L. (2020). Participation, for Whom? The Potential of Gamified Participatory Artefacts in Uncovering Power Relations within Urban Renewal Projects. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(5), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9050319