A Comprehensive Review on the Medicinal Plants from the Genus Asphodelus

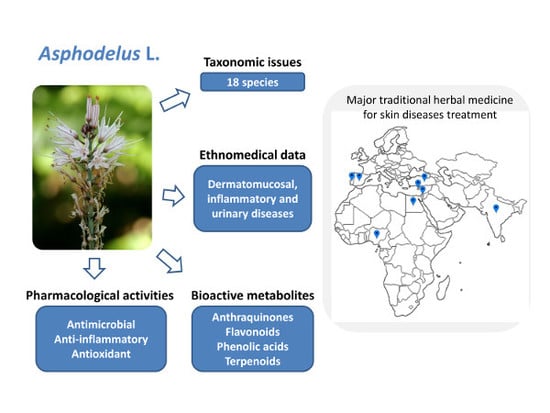

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Ethnomedical Studies

2.2. Phytochemical Studies

2.3. Reported Biological Activities

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP). Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: http://apps.kew.org/wcsp/ (accessed on 20 December 2017).

- Díaz Linfante, Z. Asphodelus L. Flora Iberica; Talavera, S., Andrés, C., Arista, M., Piedra, M.P.F., Rico, E., Crespo, M.B., Quintanar, A., Herrero, A., Aedo, C., Eds.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Real Jardin Botänico: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 20, ISBN 276-308-152. [Google Scholar]

- Cronquist, A. An Integrated System of Classification of Flowering Plants; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 9780231038805. [Google Scholar]

- Beadle, N.C.W. The Vegetation of Australia; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 0521241952. [Google Scholar]

- Rudall, P.J. Unique floral structures and iterative evolutionary themes in Asparagales: Insights from a morphological cladistic analysis. Bot. Rev. 2002, 68, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2003, 141, 399–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of floweringplants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 161, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An Ordinal Classification for the Families of Flowering Plants. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1998, 85, 531–553. [Google Scholar]

- The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016, 181, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden. 2017. Available online: http://www.tropicos.org/Name/18400528 (accessed on 20 December 2017).

- Caldas, F.B.; Moreno Saiz, J.C. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species; The International Union for the Conservation of Nature: Grand, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Talavera, S.; Andras, C.; Arista, M.; Piedra, M.P.F.; Rico, E.; Crespo, M.B.; Quintanar, A.; Herrero, A.; Aedo, C. (Eds.) Asphodelus. In Flora Iberica. Plantas Vasc. la Península Ibérica e Islas Balear; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Real Jardin Botänico: Madrid, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda, F.M.; Rizk, A.M.; Ghaleb, H.; Abdel-Gawad, M.M. Chemical and Pharmacological Studies of Asphodelus microcarpus. Planta Medica 1972, 22, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulos, L. Medicinal Plants of North Africa; Reference Publications, Inc.: Algonac, MI, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Peksel, A.; Imamoglu, S.; Altas Kiymaz, N.; Orhan, N. Antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of Asphodelus aestivus Brot. extracts. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Tejero, M.R.; Casares-Porcel, M.; Sánchez-Rojas, C.P.; Ramiro-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Molero-Mesa, J.; Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E.; Censorii, E.; de Pasquale, C.; Della, A.; et al. Medicinal plants in the Mediterranean area: Synthesis of the results of the project Rubia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Fattah, H. Chemistry of Asphodelus fistulosus. Int. J. Pharmacogn. 1997, 35, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Abu Ghdeib, S.I. Antifungal activity of plant extracts against dermatophytes. Mycoses 1999, 42, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Seedi, H.R. Antimicrobial arylcoumarins from Asphodelus microcarpus. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuhamdah, S.; Abuhamdah, R.; Al-Olimat, S.; Paul, C. Phytochemical investigations and antibacterial activity of selected medicinal plants from Jordan. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2013, 3, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, M.M.; Ma, G.; El-Hela, A.; Mohammad, A.; Kottob, S.; El-Ghaly, S.; Cutler, S.J.; Ross, S. Biologically active secondary metabolites from Asphodelus microcarpus. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amar, Z.; Noureddine, G.; Salah, R. A Germacrene—D, caracteristic essential oil from A. microcarpus Salzm and Viv. flowers growing in Algeria. Glob. J. Biodivers. Sci. Manag. 2013, 3, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rimbau, V.; Risco, E.; Canigueral, S.; Iglesias, J. Antiinflammatory activity of some extracts from plants used in the traditional medicine of north-African countries. Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghasiya, Y.; Chanda, S.V. Screening of methanol and acetone extracts of fourteen Indian medicinal plants for antimicrobial activity. Turk. J. Biol. 2007, 31, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Kalim, M.D.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Banerjee, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Oxidative DNA damage preventive activity and antioxidant potential of plants used in Unani system of medicine. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safder, M.; Imran, M.; Mehmood, R.; Malik, A.; Afza, N.; Iqbal, L.; Latif, M. Asphorodin, a potent lipoxygenase inhibitory triterpene diglycoside from Asphodelus tenuifolius. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2009, 11, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panghal, M.; Kaushal, V.; Yadav, J.P. In vitro antimicrobial activity of ten medicinal plants against clinical isolates of oral cancer cases. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2011, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, V.K.; Singh, R.B. Unsaponified Matter of Asphodelus tenuifolius Fat. Curr. Sci. 1975, 44, 723. [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud, J.; Flament, M.M.; Lussignol, M.; Becchi, M. Flavonoid content of Asphodelus ramosus (Liliaceae). Can. J. Bot. 1997, 75, 2105–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faidi, K.; Hammami, S.; Salem, A.B.; El Mokni, R.; Mastouri, M.; Gorcii, M.; Ayedi, M.T. Polyphenol derivatives from bioactive butanol phase of the Tunisian narrow-leaved asphodel (Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav., Asphodelaceae). J. Med. Plant Res. 2014, 8, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safder, M.; Mehmood, R.; Ali, B.; Mughal, U.R.; Malik, A.; Jabbar, A. New secondary metabolites from Asphodelus tenuifolius. Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, I.; Üstün, O.; Yeşilada, E.; Sezik, E.; Akyürek, N. In vivo gastroprotective effects of five Turkish folk remedies against ethanol-induced lesions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peksel, A.; Altas-Kiymaz, N.; Imamoglu, S. Evaluation of antioxidant and antifungal potential of Asphodelus aestivus Brot. growing in Turkey. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi, A.S.; Aparna, S.M.; Yadav, J.P.; Arora, D.R.; Chaudhary, U. Antimicrobial Potential of Asphodelus tenuifolius. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2013, 2, 5663–5667. [Google Scholar]

- Polatoğlu, K.; Demirci, B.; Can Başer, K.H. High Amounts of n-Alkanes in the Composition of Asphodelus aestivus Brot. Flower Essential Oil from Cyprus. J. Oleo Sci. 2016, 65, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.A. Biosystematics of the Monocotyledoneac—Flavonoid Patterns in Leaves of the Liliaceae. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1975, 3, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, B.E.; Yenesew, A.; Dagne, E. Chemotaxonomic significance of anthraquinones in the roots of asphodeloideae (Asphodelaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1995, 23, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalış, I.; Birincioǧlu, S.S.; Kırmızıbekmez, H.; Pfeiffer, B.; Heilmann, J. Secondary Metabolites from Asphodelus aestivus. Z. Naturforsch. 2006, 61, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafal, T.; Yilmaz, F.F.; Birincioğlu, S.S.; Hoşgör-Limoncu, M.; Kivçak, B. Fatty acid composition and antimicrobial activity of Asphodelus aestivus seeds. Hum. Vet. Med. 2016, 8, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oudtshoorn, M.V.R. Chemotaxonomic Investigations in Asphodeleae and Aloineae (Liliaceae). Phytochemistry 1964, 3, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Gawad, M.; Hasan, A.; Raynaud, J. Estude de l’insaponifiable et des acides gras des tuberculus d’ Asphodelus albus. Fitoterapia 1976, 47, 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Gawad, M.M.; Raynaud, J.; Netien, G. Les Anthraquinones Libres d’Asphodelus albus var. Delphinensze et d’Asphodelus cerasifer. Planta Med. 1976, 30, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynaud Par, J.; Abdel-Gawad, M.M. Contribution à L’étude Chimiotaxinomique du Genre Asphodelus (Liliaceae); Publications of the Lyon Linnéenne Society: Lyon, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hammouda, F.M.; Rizk, A.M.; Seif El-Nasr, M.M. Anthraquinones of Certain Egyptian Asphodelus Species. Z. Naturforsch. C 1974, 29, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, K.; Hammouda, F.; Rizk, A. The Constituents of the Seeds of Asphodelus microcarpus Viviani and A. fistulosus L. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1968, 20, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Qureshi, M.I.; Bhatty, M.K. Composition of the Oil of Asphodclus fistulosus (Piazi) Seeds. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1961, 38, 452–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Petrillo, A.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Era, B.; Medda, R.; Pintus, F.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Fais, A. Tyrosinase inhibition and antioxidant properties of Asphodelus microcarpus extracts. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ghaly, E.-S. Phytochemical and biological activities of Asphodelus microcarpus leaves. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Di Petrillo, A.; Fais, A.; Pintus, F.; Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Piras, V.; Orrù, G.; Mameli, A.; Tramontano, E.; Frau, A. Broad-range potential of Asphodelus microcarpus leaves extract for drug development. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, A.G.; Freire, R.; Hernández, R.; Salazar, J.A.; Suárez, E. Asphodelin and Microcarpin, Two New Bianthraquinones from Asphodelus microcarpus. Chem. Ind. 1973, 4, 851. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneim, M.M.; Elokely, K.M.; El-Hela, A.A.; Mohammad, A.; Jacob, M.; Radwan, M.M.; Doerksen, R.J.; Cutler, S.J.; Ross, S.A. Asphodosides A-E, anti-MRSA metabolites from Asphodelus microcarpus. Phytochemistry 2014, 105, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, A.M.; Hammouda, F.M.; Abdel-Gawad, M.M. Anthraquinones of Asphodelus microcarpus. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 2122–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, H.; Rizk, A.M.; Hammouda, F.M.; Abdel-Gawad, M.M. The Active Constituentes of Asphodelus microcarpus Salzm et Vivi. Qual. Plant. Mater. Veg. 1972, 21, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, M.M.; Elokely, K.M.; El-Hela, A.A.; Mohammad, A.; Jacob, M.; Cutler, S.J.; Doerksen, R.J.; Ross, S.A. Isolation and characterization of new secondary metabolites from Asphodelus microcarpus. Med. Chem. Res. 2014, 23, 3510–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, A.M.; Hammouda, F.M. Phytochemical Studies of Asphodelus microcarpus (Lipids and Carbohydrates). Planta Med. 1970, 18, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picci, V.; Cerri, R.; Ladu, M. Note di biologia e fitochimica sul genere Asphodelus (Liliaceae) di Sardegna, I Asphodelus microcarpus Salzmann e Viviani. Riv. Ital. Essenze Profum. Piante Off. 1978, 60, 647–650. [Google Scholar]

- Chimona, C.; Karioti, A.; Skaltsa, H.; Rhizopoulou, S. Occurrence of secondary metabolites in tepals of Asphodelus ramosus L. Plant Biosyst. 2013, 148, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adinolfi, M.; Corsaro, M.M.; Lanzetta, R.; Parrilli, M.; Scopa, A. A Bianthrone C-Glycoside from Asphodelus Ramosus Tubers. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzetta, R.; Parrilli, M.; Adinolfi, M.; Aquila, T.; Corsaro, M. Bianthrone C-Glucosides. 2. Three New Compounds from Asphodelus ramosus Tubers. Tetrahedron 1990, 46, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, M.; Lanzelta, R.; Marciano, C.E.; Parrilli, M.; Giulio, A.D.E. A New Class of Anthraquinone-Anthrone-C-Glycosides from Asphodelus ramosus Tubers. Tetrahedron 1991, 47, 4435–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawi, K. Comparison of the Total Phenol, Flavonoid Contents and Antioxidant Activity of Methanolic Roots Extracts of Asphodelus microcarpus and Asphodeline lutea Growing in Syria. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2017, 9, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mogib, M.; Basaif, S. Two New Naphthalene and Anthraquinone Derivatives from Asphodelus tenuifolius. Pharmazie 2002, 57, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Jaswel, S.S. Structure of an Ester from the Seeds of Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav. Indian J. Chem. 1974, 12, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, T.R.; Bhatia, I.S. Lipids of Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav. Seeds. Indian J. Bichem. Biophys. 1973, 10, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, M.U.; Alam, A.; Sinha, S.; Osman, S.M. Studies on Herbaceous Seed Oils-I. J. Oil Technol. Assoc. India 1976, 8, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, V.K.; Singh, R.B. Chemical Examination of Asphodelus tenuifolius. J. Inst. Chem. 1976, 48, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Oskay, M.; Aktaş, K.; Sari, D.; Azeri, C. Asphodelus aestivus (Liliaceae) un Antimikrobiyal Etkisinin çukur ve Disk Diffüzyon Yöntemiyle Karşilaştirmali Olarak Belirlenmesi. Ekoloji 2007, 16, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Aslantürk, S.Ö.; Çelik, T.A. Investigation of antioxidant, cytotoxic and apoptotic activities of the extracts from tubers of Asphodelus aestivus Brot. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 7, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Groshi, A.; Nahar, L.; Andrew, E.; Auzi, A.; Sarker, S.D.; Ismail, F.M.D. Cytotoxicity of Asphodelus aestivus against two human cancer cell lines. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kayali, R.; Kitaz, A.; Haroun, M. Antibacterial Activity of Asphodelin lutea and Asphodelus microcarpus Against Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2016, 8, 1964–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Aboul-Enein, A.M.; El-Ela, F.A.; Shalaby, E.A.; El-Shemy, H.A. Traditional Medicinal Plants Research in Egypt: Studies of Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghani, E. Isolation and Characterization of Bioactives from Arid Zone Plants. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2012, 4, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Howladar, S.; Mohamed, H.; Al-Robai, S. Phytochemistry, Antimicrobial, Antigiardial and Antiamoebic Activities of Selected Plants from Albaha Area, Saudi Arabia. Br. J. Med. Med. Res. 2016, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, N.; Janbaz, K.H.; Jabeen, Q. Hypotensive and diuretic activities of aqueous-ethanol extract of Asphodelus tenuifolius. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2016, 11, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, I.; Ince, O.K. Characterization of Antioxidant activity, Vitamins and Elemental Composition of Ciris (Asphodelus aestivus L.) from Tunceli, Turkey. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2017, 45, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, M.A.; Al-Meshal, I.A.; Mossa, J.S.; Khatibi, A.; Hammouda, Y. Phytochemical and Biological Screening of Saudi Medicinal Plants: Part II. Fitoterapia 1983, 1, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Apaydin, E.; Arabaci, G. Antioxidant Capacity and Phenolic Compounds with HPLC of Asphodelus ramosus and Comparison of the Results with Allium cepa L. and Allium porrum L. Extracts. Turk. J. Agric. Nat. Sci. 2017, 4, 499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-darwish, S.M.; Ateyyat, M. The Pharmacological and Pesticidal Actions of Naturally Occurring 1, 8-dihydroxyanthraquinones Derivatives. World J. Agric. Sci. 2008, 4, 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Moady, M.; Petereit, H.U. Anti-Psoriatic Composition, Method of Making and Method of Using. U.S. Patent 5,955,081A, 21 of 1999. [Google Scholar]

- García-sosa, K.; Villarreal-alvarez, N.; Lübben, P.; Peña-rodríguez, L.M. Chrysophanol, an Antimicrobial Anthraquinone from the Root Extract of Colubrina greggii. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2006, 50, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, A.K. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küpeli, E.; Aslan, M.; Gürbüż, I.; Yesilada, E. Evaluation of in vivo Biological Activity profile of Isoorientin. Z. Naturforsch. 2004, 59, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernndez, L.; Palazon, J.; Navarro-Oca, A. The Pentacyclic Triterpenes alpha, beta-amyrins: A Review of Sources and Biological Activities. Phytochem. Glob. Perspect. Role Nutr. Health 2012, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Part Used | Country | Traditional Uses/Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. aestivus | L, R | Turkey | Peptic ulcers | [32] |

| R | Turkey | Haemorrhoids, burns, wounds and nephritis | [33] | |

| NI | Cyprus, Spain | Skin diseases | [16] | |

| A. fistulosus | NI | Egypt, Libya | Fungal infections | [17] |

| A. luteus * | WP | Palestine | Dermatomucosal infections | [18] |

| A. microcarpus | FR, L, R | Egypt | Ear-ache, withering and paralysis | [13,14] |

| R | Palestine | Dermatomucosal infections | [18] | |

| R | Egypt | Ectodermal parasites, jaundice, microbial infections and psoriasis | [19,20,21] | |

| NI | Algeria | Ear-ache, eczema, colds and rheumatism | [22] | |

| A. ramosus | R | North-Africa | Inflammatory disorders | [23] |

| NI | Turkey | Anti-tumoral, diuretic and emmenagogue | [29] | |

| A. tenuifolius | L | India | Diuretic, inflammatory disorders and ulcers | [24] |

| L, SE | Egypt | Diuretic | [30] | |

| R, SE | India | Antipyretic, diuretic, colds and hemorrhoids, inflammatory disorders, rheumatic pain, ulcers and wounds | [25,27] | |

| SE | Pakistan | ulcers and inflammatory disorders | [26] | |

| WP | India | Diuretic, inflammatory disorders, bite of bees and wasps, ulcers | [28,34] | |

| NI | Pakistan | Diuretic | [31] |

| Species | Part Used | Class | Name of Compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. acaulis | L | Flavonoids | Luteolin; apigenin | [36] |

| R | Anthraquinones | Chrysophanol; asphodelin; 10,7′-bichrysophanol | [37] | |

| A. aestivus | FL | n-alkenes | Hexadecanoic acid (35.6%), pentacosane (17.4%), tricosane (13.4%), heptacosane (8.4%), heneicosane (4.5%), phytol (4.5%), tetracosane (3%), hexacosane (2%), hexahydrofarnesyl acetone (1.7%), tetradecanoic acid (1.4%), docosane (1.3%), nonadecane (1%) | [35] |

| L | Amino acids | Adenosine; tryptophan; phenylalanine | [38] | |

| Anthraquinones | Aloe-emodin; aloe-emodin acetate; chyrosphanol 1-O-gentiobioside | |||

| Flavonoids | Isovitexin; isoorientin; isoorientin 4′-O-β glucopyranoside; 6′′-O-(malonyl)-isoorientin; 6′′-O-[(S)-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaroyl]-isoorientin | |||

| Phenolic acid | Chlorogenic acid | |||

| SE | Fatty acids | Butyric acid; nervoic acid | [39] | |

| A. albus | L | Anthraquinones | Aloe-emodin; chrysophanol | [36,40] |

| Flavonoid | Luteolin | [36] | ||

| R | Anthraquinones | Chrysophanol; asphodelin; 10,7′-bichrysophanol | [37] | |

| Fatty acids | Myristic (5.3%); palmitic (18.5%); stearic (2.1%); oleic (13.5%); linoleic (44.1%); linolenic (9.9%); arachidic (2.7%); behenic (1.2%); lignoceric (2.1%) acids | [41] | ||

| Triterpenoids | β-sitosterol; β-amyrin; campesterol; stigmasterol; fucosterol | |||

| A. albus var. delphinensis | R | Anthraquinones | Asphodeline; microcorpine; aloe-emodine; chrysophanole | [42] |

| A. cerasifer | L | Anthraquinones | Aloe-emodin | [36] |

| Flavonoids | Isoorientin; luteolin; luteolin 7-glucoside | [36,43] | ||

| R | Anthraquinones | Asphodeline; microcorpine; aloe-emodine; chrysophanole | [41] | |

| * A. delphinensis | L | Flavonoids | Isoorientin; luteolin; luteolin 7-glucoside | [43] |

| A. fistulosus | AP | Anthraquinones | Asphodelin; asphodelin 10′-anthrone; aloesaponarin II; aloe-emodin; chrysophanol; desoxyerythrolaccin | [17] |

| Flavonoids | Chrysoeriol; luteolin | |||

| L | Anthraquinones | Dianhydrorugulosin; aloe-emodin; chrysophanol; 1,8 hydroxy-dianthraquinone | [44] | |

| R | Anthraquinones | Chrysophanol; asphodelin; 10,7′-Bichrysophanol | [37] | |

| SE | Anthraquinones | Dianhydrorugulosin; aloe-emodin; chrysophanol; 1,8 hydroxy-dianthraquinone | [44] | |

| Carbohydrates | Sucrose; raffinose; stachyose | [45] | ||

| Fatty acids | Myristic (0.5%); palmitic (5.7%); stearic (3.6%); oleic (33.1%); linoleic (54.9%) | [45,46] | ||

| Triterpenoids | β-sitosterol; β-amyrin | [45] | ||

| ** A. luteus | L | Anthraquinones | Aloe-emodin | [36] |

| *** A. mauritii Sennen | L | Anthraquinones | Aloe-emodin; chrysophanol | [36] |

| Flavonoids | Luteolin | |||

| A. microcarpus | FL | Terpenoids | Germacrene D (78.3%); germacrene B (3.9%); a-elemene (3.8%); caryophyllene (3.3%) | [22] |

| Flavonoids | Luteolin; luteolin-6-C-glucoside; luteolin-O-hexoside; luteolin-7-O-glucoside; luteolin-O-acetylglucoside; luteolin-O-deoxyhesosylhexoside; methyl-luteolin, naringenin; apigenin | [47] | ||

| Phenolic acids | 3-O caffeoylquinic acid; 5-O caffeoylquinic acid | |||

| L | Anthraquinone | Chrysophanol, 10 (chrysophanol-7-yl)-10-Hydroxychrysophanol-9-antrone, asphodoside C, Dianhydrorugulosin; aloe-emodin | [44,48] | |

| Flavonoids | Luteolin-6-C-glucoside; luteolin-6-c-acetilglucoside; luteolin-C-glucoside; luteolin, isoorientin | [43,49] | ||

| Phenolic acids | 5-O caffeoylquinic acid; cichoric acid; cumaril exosa malic acid | [49] | ||

| R | Anthraquinones | Dianhydrorugulosin; aloe-emodin; chrysophanol; asphodelin; microcarpin, 8 methoxychrysophanol; emodin; 10-(chrysophanol-7′-yl)-10-hydroxychrysophanol-9-anthrone; aloesaponol-III-8-methyl ether; ramosin; aestivin, asphodosides A-E, chrysophanol dianthraquinone; 5,5′-bichrysophanol; chrysophanol-8-mono-β-d-glucoside; Methyl-1,4,5-trihydroxy-7-methyl-9,10-dioxo-9,10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxylate; 6 methoxychrysophanol | [21,44,50,51,52,53,54] | |

| Arylcoumarins | Asphodelin A 4′-O-β-d-glucoside; asphodelin A | [19] | ||

| Carbohydrates | Raffinose; sucrose; glucose; fructose | [55] | ||

| Fatty acids | Palmitic; stearic; oleic; linoleic; linolenic; arachidic; behenic; lignoceric; myristic acids | [55,56] | ||

| Naphthalene derivatives | 2-acetyl-1,8-dimethoxy-3 methylnaphthalene; 1,6-dimethoxy-3-methyl-2-naphthoic acid | [21] | ||

| Mucilage | Composed of glucose; galactose; arabinose | [55] | ||

| Triterpenoids | β-sitosterol-β-d-glucoside, fucosterol | [13,55] | ||

| SE | Anthraquinones | Aloe-emodin; chrysophanol; chrysophanol-8-mono-β-d-glucoside | [44] | |

| Carbohydrates | Sucrose; raffinose; stachyose; melibiose | [45] | ||

| Fatty acids | Myristic; palmitic; stearic; oleic; linoleic acids | |||

| Triterpenoids | β-sitosterol; β-amyrin | |||

| A. ramosus | FL | Flavonoids | Luteolin | [57] |

| Phenolic acids | Caffeic acid; chlorogenic acid; p-hydroxy-benzoic acids | |||

| L | Flavonoids | Luteolin; 7-O-glucosyl luteolin; 7-O-glucosyl apigenin; isoorientin; isoswertiajaponin (7-methyl orientin); isocytisoside (4′-methyl vitexin) | [29] | |

| R | Anthraquinone | Ramosin; (−)-10′-C-[β-d-xylopyranosyl]-; (−)-10′-C-[β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1-4)-β-d-glucopyranosyl]-1,1′,8,8,10,10′-hexa hydroxy -3,3′-dimethyl-10,7′ bianthracene-9,9′-dione; 10′-deoxy-10-epi-ramosin; 10-(chrysophanol-7′-yl)-10-hydroxychrysophanol-9-anthrone; 7′-(Chrysophanol-4-yl)-chrysophanol-10′anthrone10′-C-α-rhamnopyranosyl; -C-β-xylopyranosyl; -C-β-antiaropyranosyl; -C-α-arabinopyranosyl; -C-β-quinovoopyranosyl | [58,59,60] | |

| WP | Flavonoids | Naringin, quercetin, kaemferol | [61] | |

| Phenolic acids | Gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanilic acid, cafeic acid | |||

| A. tenuifolius | AP | Flavonoids | Luteolin; luteolin-7-O-β-d-glycopyranoside; apigenin, chrysoeriol | [30] |

| R | Naphthalene derivatives | 1,8-dimethylnaphthalene; 2-acetyl-8-methoxy-3-methyl-1-naphthol; 2-acetyl-1,8-dimethoxy-3-methylnaphthalene | [62] | |

| Triterpenoids | β-sitosterol; stigmasterol | |||

| SE | Ester | 1-O-17methylstearylmyoinositol | [63] | |

| Fatty acids | Myristic (3.96%); palmitic (13.84%); oleic (15.60%); linoleic (62.62%); linolenic (2.60%) | [64,65] | ||

| WP | Amino acids | Crystine; serine; glycine; proline; alanine, glycin; serine; alanine and valine in the form of protein | [66] | |

| Carbohydrates | d-glucose; lactose; d-glucuronic acid; d-arabinose; d-fructose, d-ribose | |||

| Chromone | 2-hentriacontyl-5,7-dihydroxy-8-methyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one | [31] | ||

| Triterpenoids | Asphorodin; asphorin A; asphorin B; β-sitosterol; β-amyrin | [26,28,31] |

| Species | Part | Extract | Test/Assay | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. aestivus | L | Aqueous, Ethanol | In vitro anti-fungal activity (A. niger)—Agar well diffusion method (zone of inhibition in cm−1) | Ethanol extract (0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL) showed higher activity than aqueous extract (0.25 and 0.5 mg/mL) and similar activity for concentrations of 1 mg/mL. Both extracts were less active than Fluconazole (100 µ/mL) | [33] |

| In vitro antioxidant activity—β-carotene bleaching effect, metal chelating, total antioxidant activity, DPPH, ABTS, superoxide radical scavenging activity, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, DMPD, nitric oxide scavenging activity | Aqueous extract presented higher activity in metal chelating and radical scavenging assays (DPPH, IC50 aqueous = 4.58 mg/mL and IC50 methanol = 9.54 mg/mL, superoxide, hydroxyl, DMPD) Ethanol extract presented higher activity in β-carotene bleaching effect and total antioxidant activity Aqueous and ethanolic extracts presented similar radical scavenging activity in ABTS and NO assays. Both extracts presented significantly inferior results when compared to reference substances | ||||

| A. aestivus | L | Acetone, Methanol | In vitro antioxidant activity—β-carotene, reducing power assay, DPPH, ABTS, inhibition of linoleic acid peroxidation, superoxide radical scavenging assays | Reducing power and total antioxidant activity were higher in acetone extract; free radical and superoxide radical scavenging activity were higher in methanol extract (DPPH, IC50 methanol = 0.16 mg/mL and IC50 acetone = 0.50 mg/mL) Acetone extract presented higher activity in Reducing power and total antioxidant activity (inhibition of linoleic acid peroxidation) Methanol extract presented higher activity in superoxide radical scavenging and free radical scavenging activity (β-carotene, ABTS and DPPH, IC50 methanol =0.16 mg/mL, IC50acetone = 0.50 mg/mL) | [15] |

| A. aestivus | L, R | Dichloromethane n-Hexane | In vitro cytotoxic activity—MTT assay against human lung cell cancer (A549) and prostate cell cancer (PC3) | Root: Dichloromethane: A549 (IC50 = 16 µg/mL); PC3 (IC50 = 19 µg/mL) n-Hexane: PC3 (IC50 = 80 µg/mL) Leaves: Dichloromethane: A549 (IC50 = 90 µg/mL) | [69] |

| A. aestivus | R | Aqueous (decoction) | In vivo anti-inflammatory—Ethanol induced gastric ulcer model in rats | Decoction gave significant protection against the lesions | [32] |

| A. aestivus | R | Aqueous (infusion and decoction) Diethyl ether, Ethyl acetate, Methanol | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH assay | Diethyl ether (IC50 = 22.46 µg/mL) have a higher scavenging activity than Ethyl acetate (IC50 = 188.90 µg/mL), both have lower activity than reference substance, rutin (7.77 µg/mL). Methanol and aqueous extract had no scavenging activity | [68] |

| In vitro cytotoxic & apoptotic activity—MCF-7 breast cancer cells-trypan blue exclusion assay, comet assay, Hoechst 33,258, propidium iodide double staining | Methanol and aqueous extracts exhibited strong cytotoxic activities. All extracts showed significant DNA damaging and apoptotic activities. | ||||

| A. aestivus | SE | Petroleum ether | In vitro antimicrobial/fungal activity—broth microdilution method | Active against S. aureus (MIC = 512 µg/mL), Enteroococcus faecalis (MIC = 512 µg/mL), K. pneumoniae (MIC = 512 µg/mL) and C. albicans (MIC = 512 µg/mL) Not active against Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhimurium, Salmonella enterica, Candida krusei and Candida parapsilosis | [39] |

| A. aestivus | WP | n-Butanol, Ethanol | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity—well and disk diffusion method | Active against S. aureus (MIC: 42 mg/mL), K. pneumoniae (MIC: 60 mg/mL), E. coli (MIC: 90 mg/mL), C. albicans (MIC: 90 mg/mL) | [67] |

| A. aestivus | WP | Aqueous | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH assay | Inhibition % = 62.5 | [75] |

| A. fistulosus var. tenuifolius | NI | NI | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity | Positive to S. aureus and no activity against E. coli, Proteus vulgaris, Salmonella sp., P. aeruginosa, C. albicans | [76] |

| A. luteus * | AP | Aqueous | In vitro anti-fungal activity—Agar dilution method | Activity against T. violaceum (MIC = 18 µg/mL), M. canis (MIC = 25 µg/mL) and T. mentagrophytes (MIC = 30 µg/mL) | [18] |

| A. luteus * | AP R | Methanol, Petroleum Ether | In vitro anti-microbial activity—agar diffusion test; tetrazolium microplate assay (MIC) | Against MRSA isolates Methanol extract: MIC (AP) = 1.25–2.5 mg/mL MIC (R) = 0.65–1.25 mg/mL Petroleum ether extract: Root extract had higher activity than aerial part extract | [70] |

| A. luteus * | R | Methanol | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH assay | IC50 (methnol)= 0.54 mg/mL, IC50 (reference, BHT) = 0.017 mg/mL | [61] |

| A. microcarpus | AP | Aqueous | In vitro anti-fungal activity—Agar dilution method | Weak activity against T. violaceum (MIC = 25 µg/mL) and no activity against M. canis and T. mentagrophytes | [18] |

| A. microcarpus | AP R | Methanol | In vitro anti-microbial activity—agar diffusion test; tetrazolium microplate assay (MIC) | Against MRSA isolates Methanol extract: MIC (AP) = 1.25–5 mg/mL MIC (R) = 1.25–2.5 mg/mL | [70] |

| A. microcarpus | FL L R | Aqueous, Ethanol, Methanol | In vitro antimelanogenic activity—tyrosinase inhibition (mushroom tyrosinase assay and mouse melanoma cells viability), kojic acid as positive control | Antimelanogenic activity Ethanol extract (F) had the highest tyrosinase inhibition activity in mushroom assay and melanoma cell assay | [47] |

| In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH and ABTS (reference—Trolox) | Antioxidant activity DPPH (best activity) Ethanol extract (F): IC50 = 28.4 µg/mL Ethanol extract (L): IC50 = 55.9 µg/mL Trolox: IC50 = 3.2 µg/mL | ||||

| A. microcarpus | L | Ethanol | In vitro antimicrobial/fungal activity—micro broth dilution method | Active against Bacillus clausii (MIC = 250 µg/mL), S. aureus (MIC = 250 µg/mL), Staphylococcus haemolyticus (MIC = 250 µg/mL) and E. coli (MIC = 500 µg/mL). No activity against Streptococcus spp. and yeasts | [49] |

| In vitro antiviral activity (IFN-β induction)—luciferase reporter gene assay | Antiviral activity Active against EBOV in concentration of 0.1–3 µg/mL | ||||

| In vitro cytotoxicity-Cell viability of A549 cells, positive control (camptothecin) | Cytotoxicity IC50 (extract) > 100 µg/mL IC50 (camptothecin) = 0.54 µg/mL | ||||

| A. microcarpus | L | Methanol | In vitro antimicrobial/fungal—two-fold serial dilution technique | Antimicrobial activity Active against S. aureus (MIC = 78 µg/mL), Bacillus subtilis (MIC = 156 µg/mL), Salmonella spp. (MIC = 313 µg/mL), E. coli (MIC = 125 µg/mL), Aspergillus flavus (MIC = 125 µg/mL), C. albicans (MIC = 78 µg/mL) | [48] |

| In vitro antiviral activity—CPE inhibition assay against HSV-1 and HAV-10 | Antiviral activity Moderate activity against Hepatitis A virus (HAV-10) and no activity against Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) | ||||

| In vitro cytotoxicity—viability assay against human tumor cell lines of the lung (A-549), colon (HCT-116), breast (MCF-7) and prostate (PC3). Cisplatin as standard | Cytotoxicity Highest activity against human lung carcinoma cells (A-549), IC50 = 29.3 µg/mL | ||||

| A. microcarpus | R | Methnol | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH assay | IC50 (Methnol) = 0.30 mg/mL, IC50 (reference, BHT) = 0.017 mg/mL | [61] |

| A. microcarpus | R | Methanol | In vitro anti-microbial—Disk diffusion assay | No activity against S. aureus, B. subtilis and E. coli | [20] |

| A. microcarpus | WP | Aqueous, Ethanol | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH assay | Ethanol extract (100 µg/mL) with moderate activity (inhibition percentage—60.3%) higher than aqueous extract (100 µg/mL, inhibition percentage—49.5%) | [71] |

| In vitro cytotoxic activity—Trypan blue technique for Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma Cells (EACC) | Weak anti-cancer activity of both extracts | ||||

| A. ramosus | R | Aqueous, Chloroform, Ethanol, Methanol | In vivo anti-inflammatory—Arachidonic acid test (mouse ear oedema) Carrageenan test (sub-plantar oedema) | Arachidonic acid test: Positive activity from chloroform and ethanol extracts Carrageenan test: No activity was observed | [23] |

| A. ramosus | WP | Aqueous, Methanol, Methanol 50% | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH assay at 35 °C and 65 °C | Aqueous extract at 65 °C had the highest inhibition percentage | [77] |

| A. tenuifolius | AP | Butanol, Ethyl acetate, Methylene-chloride | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity—Disc diffusion method | All extracts showed antimicrobial activity, the methylene-chloride as the most active against S. aureus (MIC = 1.6 mg/mL), E. faecalis (MIC = 1.0 mg/mL), E. coli (MIC = 1.8 mg/mL) and P. aeruginosa (MIC = 0.15 mg/mL) All extracts showed antifungal activity against C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. krusei. | [30] |

| A. tenuifolius | FR | Acetone, Aqueous, Benzene, Chloroform, Methanol, Petroleum ether | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity—Kirk-bauer disc diffusion method | Significant activity against S. aureus (acetone, MIC = 125 µg/mL); S. epidermidis (acetone, MIC = 125 µg/mL; chloroform and methanol, MIC = 250 µg/mL); P. vulgaris (methanol, MIC = 250 µg/mL; chloroform, MIC = 125 µg/mL), P. mirabilis (benzene, MIC = 125 µg/mL; acetone and methanol, MIC = 250 µg/mL; chloroform, MIC = 500 µg/mL) E. coli (acetone, chloroform and methanol, MIC = 125 µg/mL); K. pneumoniae (acetone and methanol, MIC = 125 µg/mL; chloroform and benzene, MIC = 500 µg/mL); P. aeruginosa (acetone, MIC = 250 µg/mL; chloroform, MIC = 500 µg/mL); C. albicans (acetone, MIC = 125 µg/mL); A. fumigatus (benzene and chloroform, MIC = 250 µg/mL; acetone, MIC = 500 µg/mL) | [27] |

| A. tenuifolius | L | Acetone, Methanol | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity—Agar disc diffusion method | Methanol extract positive against S. aureus, B. cereus, Citrobacter freundii, Candida tropicalis and acetone extract was positive against K. pneumoniae, C. tropicalis and Cryptococcus luteolus | [24] |

| A. tenuifolius | R | Methanol | In vitro antioxidant activity—DPPH, ABTS+, NO, OH, O2−, ONOO− assays, Oxidative DNA damage | Positive activity, DPPH (IC50 = 2.006 µg/mL), ABTS·+ (IC50 = 156.94 µg/mL), NO (nd), OH (IC50 = 50.13 µg/mL), O2− (IC50 = 425.92 µg/mL) and ONOO- (IC50 = 3.390 µg/mL), oxidative DNA damage: 1.85 µg/mL of extract prevented DNA damage. | [25] |

| A. tenuifolius | R | Benzene, Chloroform, Ethyl acetate, Methanol, Petroleum ether | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity—Disc diffusion method | All extracts were active against B. subtilis, P. vulgaris, P. aeruginosa, Trichophyton rubrum, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Shigella sonnei, S. aureus, C. albicans, A. niger and A. flavus | [72] |

| A. tenuifolius | SE | Aqueous, Ethanol, Methanol, Petroleum ether | In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity—modified Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method | Petroleum ether: no antibacterial activity Ethanol: activity against P. aeruginosa, Vibrio cholerae and S. aureus (MIC = 16 µg/mL); P. mirabilis, S. typhi, Shigella flexneri and Serratia marcescens (MIC = 32 µg/mL). Methanol: activity against S. aureus (MIC = 16 µg/mL); V. cholerae, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi, S. flexneri and S. marcescens (MIC = 16 µg/mL) Aqueous: activity against V. cholerae, S. aureus, S. typhi and S. flexneri (MIC = 32 µg/mL); P. aeruginosa and P. mirabilis (MIC = 16 µg/mL). No antifungal activity against C. albicans and A. niger | [34] |

| A. tenuifolius | WP | Methanol | In vitro antimicrobial/fungal activity—disk diffusion method In vitro anti-parasitic activity—trophozoites growth inhibition assay | Good activity against E. coli and moderate activity against S. aureus, S. typhi, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans and A. niger Active against Giardia lamblia (IC50 = 219.82 µg/mL) and Entamoeba histolytica (IC50 = 344.62 µg/mL) | [73] |

| A. tenuifolius | WP | Aqueous | In vivo hypotensive activity—blood pressure (BP) measure after parenteral administration of aqueous extracts in rats. Acetylcholine and verapamil as positive controls in co administration with atropine | Hypotensive activity The extract decreased blood pressure in normotensive rats (35.2% decrease with 30 mg/Kg), similar to Verapamil. The response was independent from atropine effect | [74] |

| In vivo diuretic activity—measure of rat urine output and urinary electrolytes. After 6 hr administration. Saline solution and furosemide as controls | Diuretic activity Significant increase in urinary volume and electrolytes excretion with 300 and 500 mg/Kg |

| Species | Pure Compounds | Test/Assay | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. microcarpus | Asphodelin A 4′-O-β-d-glucoside (1), Asphodelin A (2) | In vitro antimicrobial/fungal activity—micro dilution assay | S. aureus (MIC1 = 128 µg/mL, MIC2 = 16 µg/mL), E. coli (MIC1 = 128 µg/mL, MIC2 = 4 µg/mL), P. aeruginosa (MIC1 = 256 µg/mL, MIC2 = 8 µg/mL), C. albicans (MIC1 = 512 µg/mL, MIC2 = 64 µg/mL) and B. cinerea (MIC1 = 1024 µg/mL, MIC2 = 128 µg/mL | [19] |

| 3-methyl anthraline, chrysophanol, and aloe-emodine | Psoriasis | Positive (patent) | [78,79] | |

| 1,6-dimethoxy-3-methyl-2-naphthoic acid (1), asphodelin (2), chrysophanol (3), 8 methoxychrysophanol (4), emodin (5), 2-acetyl-1,8-dimethoxy-3-methylnaphthalene (6), 10-(chrysophanol-7′-yl)-10-hydroxychrysophanol-9-anthrone (7), aloesaponol-III-8-methyl ether (8), ramosin (9), aestivin (10) | In vitro anti-parasitic activity | Compounds 3 and 4 showed moderate to weak against a culture of L. donovani promastigotes (IC50 = 14.3 and 35.1 μg/mL, respectively) | [21] | |

| In vitro cytotoxic activity-Human acute leukemia HL60 cells/human chronic leukemia 562 cells | Compounds 7 and 9 exhibited a potent cytotoxic activity against leukemia LH60 and K562 cell lines | |||

| In vitro antimalarial activity—chloroquine sensitive & resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum (plasmodial LDH activity) | Compound 10 showed potent antimalarial activities against both chloroquine-sensitive and resistant strains of P. falciparum (IC50 = 0.8–0.7 μg/mL) without showing any cytotoxicity to mammalian cells | |||

| In vitro anti-microbial/fungal activity | Compound 4 exhibited moderate antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans (IC50 = 15.0 μg/mL), compounds 5, 7 and 10 showed good to potent activity against methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (IC50 = 6.6, 9.4 μg/mL and 1.4 μg/mL respectively). Compounds 5, 8 and 9 displayed good activity against S. aureus (IC50 = 3.2, 7.3 and 8.5 μg/mL, respectively) | |||

| Methyl-1,4,5-trihydroxy-7-methyl-9,10-dioxo-9,10-dihydroanthracene-2-carboxylate (1), (1R) 3,10-dimethoxy-5-methyl-1H-1,4 epoxybenzo[h]isochromene (2), 3,4-dihydroxy-methyl benzoate (3), 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (4), 6 methoxychrysophanol (6) | In vitro anti-parasitic activity | Compound 3 showed activity against a culture of L. donovani promastigotes (IC50 = 33.2 µg/mL) | [54] | |

| In vitro anti-microbial/activity | Compound 1 showed a potent activity against methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and S. aureus (IC50: 1.5 and 1.2 µg/mL, Respectively) | |||

| 5 Compounds, Asphodosides A–E | In vitro anti-microbial activity | Compounds 2–4 showed activity against methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) (IC50: 1.62, 7.0 and 9.0 µg/mL, respectively). activity against S. aureus (non-MRSA), IC50 = 1.0, 3.4 and 2.2 µg/mL, respectively | [51] | |

| A. tenuifolius | Asphorodin | In vitro anti-inflammatory-inhibition of lipoxigenase enzyme | Potent inhibitory activity (IC50 = 18.1 µM), Reference: baicalein (22.6 µM) | [26] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malmir, M.; Serrano, R.; Caniça, M.; Silva-Lima, B.; Silva, O. A Comprehensive Review on the Medicinal Plants from the Genus Asphodelus. Plants 2018, 7, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants7010020

Malmir M, Serrano R, Caniça M, Silva-Lima B, Silva O. A Comprehensive Review on the Medicinal Plants from the Genus Asphodelus. Plants. 2018; 7(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants7010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalmir, Maryam, Rita Serrano, Manuela Caniça, Beatriz Silva-Lima, and Olga Silva. 2018. "A Comprehensive Review on the Medicinal Plants from the Genus Asphodelus" Plants 7, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants7010020

APA StyleMalmir, M., Serrano, R., Caniça, M., Silva-Lima, B., & Silva, O. (2018). A Comprehensive Review on the Medicinal Plants from the Genus Asphodelus. Plants, 7(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants7010020