Illustrating the Multi-Faceted Dimensions of Group Therapy and Support for Cancer Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Groups Studied

2.1.1. Stanford Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy (SET)

2.1.2. The Wellness Community (TWC) Now Called the Cancer Support Community (CSC)

2.1.3. Non-Therapist-Led Groups (NTL)

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Group Satisfaction Ratings

2.2.2. Group Experiences Questionnaire Development (GEQ)

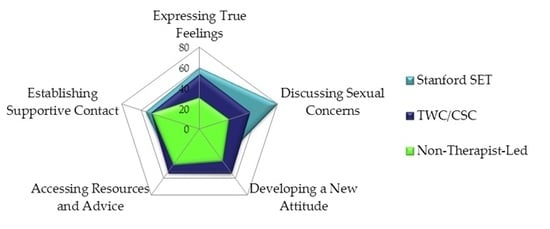

- Expressing True Feelings (4 items): Expressing my true feelings; Talking about fears of death and suffering; Confronting difficult problems and fears; Getting honest feedback from others.

- Discussing Sexual Concerns (1 item): Discussing Sexual Concerns.

- Developing a New Attitude (6 items): Developing a new attitude toward life; Changing my behaviour in ways that feel satisfying; Gaining insight about myself; Owning up to maladjustment when it seems important; Learning that I am responsible for how I cope with my life; Becoming hopeful.

- Accessing Resources and Advice (3 items): Gaining access to important information; Getting direct advice, suggestions, or education; Getting new understandings or explanations.

- Establishing Supportive Contact (9 items): Talking about everyday things and socializing; Developing new friendships; Belonging to and being accepted by a group; Playing my part at the meeting; Being encouraged to talk more; Modelling myself after other group members; Getting support and encouragement; Helping others; Making contact with someone who I could call on for help.

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial Psychometrics and Satisfaction

Satisfaction

3.2. GEQ Between-Group Analysis

3.2.1. Expressing True Feelings

3.2.2. Discussing Sexual Concerns

3.2.3. Developing a New Attitude

3.2.4. Accessing Resources and Advice

3.2.5. Establishing Supportive Contact

3.3. Within-Group Analysis

3.4. Radar Chart Profiles of Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TL | Therapist-led |

| SET | Supportive-Expressive Group Therapy |

| TWC | The Wellness Community |

| CSC | Cancer Support Community |

| NTL | Non-therapist-led |

| GEQ | Group Experience Questionnaire |

| MFCC | Marriage, Family, & Child Counsellor |

References

- Cassel, J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1976, 104, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cobb, S. Presidential address-1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, J.E.; Goldstein, M.S.; Lee, J.H.; Breen, N.; Rowland, J.H. Use of health-related and cancer-specific support groups among adult cancer survivors. Cancer 2007, 109, 2580–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ussher, J.; Kirsten, L.; Butow, P.; Sandoval, M. What do cancer support groups provide which other supportive relationships do not? The experience of peer support groups for people with cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 2565–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, M.; Cappella, J.N.; Han, J.Y. How does insightful and emotional disclosure bring potential health benefits? Study based on online support groups for women with breast cancer. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 432–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.A. Analyzing change mechanisms in groups. In Self-Help Groups for Coping with Crisis; Lieberman, M.A., Borman, L.D., Eds.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 194–233. [Google Scholar]

- Terrill, A.; Ruiz, J.; Garofalo, J. Look on the bright side: Do the benefits of optimism depend on the social nature of the stressor? J. Behav. Med. 2010, 33, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.G.C.; Pincus, A.; Conroy, D.; Hilsenroth, M. Integrating methods to optimize circumplex description and comparison of groups. J. Pers. Assess. 2009, 91, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colibazzi, T.; Posner, J.; Wang, Z.; Gorman, D.; Gerber, A.; Yu, S.; Zhu, H.; Kangarlu, A.; Duan, Y.; Russell, J.; et al. Neural systems subserving valence and aroUSAl during the experience of induced emotions. Emotion 2010, 10, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhriman, A.; Burlingame, G.M. The hill interaction matrix: Therapy through dialogue. In The Process of Group Psychotherapy: Systems for Analyzing Change; Beck, A.P., Lewis, C.M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 135–174. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T.J.; Mark, M.M. Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychol. 1995, 14, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, C.V.I.; Lockwood, G.A.; Cunningham, A.J. Psychological response to long term group therapy: A randomized trial with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 1999, 8, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V.S.; Cohen, S.; Schulz, R.; Yasko, J. Group support interventions for women with breast cancer: Who benefits from what? Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagl, J.M.; Bounchard, L.C.; Lechner, S.C.; Blomberg, B.B.; Gudenkauf, L.M.; Jutagir, D.R.; Gluck, S.; Derhagopian, R.P.; Carver, C.S.; Antoni, M.H. Long-term psychological benefits of cognitive-behavioral stress management for women with breast cancer: 11-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2015, 121, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechner, S.C.; Whitehead, N.E.; Vargas, S.; Annane, D.W.; Robertson, B.R.; Carver, C.S.; Kobetz, E.; Antoni, M.H. Does a community-based stress management intervention affect psychological adaptation among underserved black breast cancer survivors? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2014, 2014, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, M.; Carson Stevens, A.; Gillespie, D.; Edwards, A.G.K. Psychological interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, P.J.; Leszcz, M.; Ennis, M.; Koopmans, J.; Vincent, L.; Guther, H.; Drysdale, E.; Hundleby, M.; Chochinov, H.M.; Navarro, M.; et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, D.; Bloom, J.R.; Yalom, I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1981, 38, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Classen, C.; Butler, L.D.; Koopman, C.; Miller, E.; DiMiceli, S.; Giese-Davis, J.; Fobair, P.; Carlson, R.W.; Kraemer, H.C.; Spiegel, D. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical intervention trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, E.N.; Kohorn, E.I.; Quinlan, D.M.; Latimer, K.; Schwartz, P.E. Psychosocial benefits of a cancer support group. Cancer 1986, 57, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.L.; Farrar, W.B.; Golden-Kreutz, D.M.; Glaser, R.; Emery, C.F.; Crespin, T.R.; Shapiro, C.L.; Carson, W.E., III. Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: A clinical trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3570–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, D.; Bloom, J.R. Group therapy and hypnosis reduce metastatic breast carcinoma pain. Psychosom. Med. 1983, 45, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, L.; Koopman, C.; Neri, E.; Giese-Davis, J.; Palesh, O.; Thorne-Yocam, K.; Dimiceli, S.; Chen, X.-H.; Fobair, P.; Kraemer, H.; et al. Effects of supportive-expressive group therapy on pain in women with metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akechi, T.; Okuyama, T.; Onishi, J.; Morita, T.; Furukawa, T.A. Psychotherapy for depression among incurable cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese-Davis, J.; Koopman, C.; Butler, L.D.; Classen, C.; Cordova, M.; Fobair, P.; Benson, J.; Spiegel, D. Change in emotion regulation-strategy for women with metastatic breast cancer following supportive-expressive group therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, F.I.; Fawzy, N.W.; Hyun, C.S.; Elashoff, R.; Guthrie, D.; Fahey, J.L.; Morton, D.L. Limalignant melanoma. Effects of an early structured psychiatric intervention, coping, and affective state on recurrence and survival 6 years later. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1993, 50, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, B.L.; Thornton, L.M.; Shapiro, C.L.; Farrar, W.B.; Mundy, B.L.; Yang, H.-C.; Carson, W.E. Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 3270–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni, M.; Lutgendorf, S.; Blomberg, B.; Carver, C.; Lechner, S.; Diaz, A.; Stagl, J.; Arevalo, J.M.G.; Cole, S. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reverses anxiety-related leUKocyte transcriptional dynamics. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 71, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.E.; Beattie, T.L.; Giese-Davis, J.; Faris, P.; Tamagawa, R.; Fick, L.J.; Degelman, E.S.; Speca, M. Mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy maintain teLomere length relative to controls in distressed breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2015, 121, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glajchen, M.; Magen, R. Evaluating process, outcome, and satisfaction in community-based cancer support research. Soc. Work Groups 1995, 18, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, A.C.; Leszcz, M.; Mosier, J.; Burlingame, G.M.; Cleary, T.; Ulman, K.H.; Simonton, S.; Latif, U.; Strauss, B.; Hazelton, L. Group interventions for patients with cancer and hiv disease: Part III. Moderating variables and mechanisms of action. Int. J. Group Psychother. 2004, 54, 347–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.; Golant, M. Leader behavior as perceived by cancer patients in professionally directed support groups and outcomes. Group Dyn. 2002, 6, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.A.; Golant, M.; Altman, T. Therapeutic norms and patient benefit: Cancer patients in professionally directed support groups. Group Dyn. 2004, 8, 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Tamagawa, R.; Li, Y.; Gravity, T.; Piemme, K.; DiMiceli, S.; Collie, K.; Giese Davis, J. Deconstructing therapeutic mechanisms in cancer support groups: Do we express more emotion when we tell stories or talk directly to each other? J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.A. Effects of disease and leader type on moderators in online support groups. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.; Butow, P.; Kirsten, L. Support and training needs of cancer support group leaders: A review. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S.J.; Keyton, J. Facilitating social support: Member-leader communication in a breast cancer support group. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, E36–E43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalom, I.D.; Leszcz, M. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 5th ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan, D.M., Jr. Endorsement of therapeutic factors as a function of stage of group development and participant interpersonal attitudes. J. Counsel. Psychol. 1991, 38, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.R. Therapeutic factors in group psychotherapy: A contemporary view. Group 1987, 11, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupnick, J.; Rowland, J.; Goldberg, R.; Daniel, U. Professionally-led support groups for cancer patients: An intervention in search of a model. Psychiatry Med. 1993, 23, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magen, R.H.; Glajchen, M. Cancer support groups: Client outcome and the context of group process. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 1999, 9, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, S.M.; Powell, L.H.; Adler, N.; Naar-King, S.; Reynolds, K.D.; Hunter, C.M.; Laraia, B.; Olster, D.H.; Perna, F.M.; Peterson, J.C.; et al. From ideas to efficacy: The orbit model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, H. The Wellness Community Guide to Fighting for Recovery from Cancer; Putnam: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, D.; Classen, C. Group Therapy for Cancer Patients: A Research-Based Handbook of Psychosocial Care; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J.M.; Cleveland, W.S.; Kleiner, B.; TUKey, P.A. Graphical Methods for Data Analysis; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Friendly, M. The sas® system for statistical graphics—A preview. In Proceedings of the SAS User’s Group International Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 1–4 April 1990; pp. 1425–1430.

- Wikipedia. Radar Chart. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radar_chart (accessed on 20 July 2016).

- Saary, M.J. Radar plots: A useful way for presenting multivariate health care data. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalom, I.D. Existential Psychotherapy; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Golant, M.; Thiboldeaux, K. The wellness community’s integrative model of evidence-based psychosocial services, programs and interventions. In Psycho-Oncology, 2nd ed.; Holland, J.C., Breitbart, W.S., Jacobsen, P.B., Lederberg, M.S., Loscalzo, M.J., McCorkle, R.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar]

- Liess, A.; Ellis, W.; Yutsis, M.; Owen, J.; Piemme, K.A.; Golant, G.; Giese-Davis, J. Detecting emotional expression in face-to-face and online breast cancer support groups. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, M.J.; Giese-Davis, J.; Golant, M.; Kronnenwetter, C.; Chang, V.; Spiegel, D. Breast cancer as trauma: Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2007, 14, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese-Davis, J. Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. Group Experiences Questionnaire. Unpublished Self-Report Scale. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L.J. The appeal of mutual help: The participant’s perspective. In Proceedings of the Social Policy Research in Action Conference, Columbia, SC, USA, 15 May 1987.

- Stanton, A.L.; Ganz, P.A.; Rowland, J.H.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Krupnick, J.L.; Sears, S.R. Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer 2005, 104, 2608–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, A.L. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5132–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, M.A. Comparative analyses of change mechanisms in groups. In Small Groups and Social Interaction; Blumberg, H.H., Hare, A.P., Kent, V., Davies, M., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 2, pp. 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, revised ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, S.A.; Murray, D.M.; Shadish, W.R. Empirically supported treatments or type I errors? Problems with the analysis of data from group-administered treatments. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 73, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devitt, B.; Hatton, A.; Baravelli, C.; Schofield, P.; Jefford, M.; Mileshkin, L. What should a support program for people with lung cancer look like? Differing attitudes of patients and support group facilitators. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, W.; Phillips, C.J. Interprofessional collaboration: A stakeholder approach to evaluation of voluntary participation in community partnerships. J. Interprof. Care 2001, 15, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, H.C.; Stice, E.; Kazdin, A.; Offord, D.; Kupfer, D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Therapist-Led | Non-Therapist-Led | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Stanford SET (n = 20) | TWC/CSC (n = 224) | Self-Help, Lecture/Discussion, Social Groups (n = 48) |

| Setting | University Randomized Trial | Community Clinical setting | Community Hospital, ACS Cansurmount, and Community Randomized Trial |

| Location | S.F. Bay Area, CA | 6 Sites in CA | Champaign-Urbana, IL and S.F. Bay Area |

| Format | Facilitated, Unstructured Emotional Support | Facilitated, Unstructured Emotional Support | Un-Facilitated, Unstructured Emotional Support, Structured Lectures/Discussion |

| Leadership Style | Supportive-Expressive | Patient-Active Concept | Peer-led, Lecture, and Un-led |

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Meeting Size | 5.75 (2.24) | 9.16 (2.40) | 14.22 (12.47) |

| Meeting Length (h) | 1.50 (0.0) | 2.00 (0.0) | 5.22 (13.94) |

| Meetings per Month | 4.00 (0.0) | 4.00 (0.0) | 2.79 (4.50) |

| % Women | 100 | 69.1 | 78.9 |

| % Breast Cancer | 100 | 23.9 | 30.3 |

| % Metastatic | 100 | 39.6 | 15.0 |

| Characteristic | Therapist-Led | Non-Therapist-Led | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Stanford SET (n = 20) | TWC/CSC (n = 224) | Self-Help, Lecture/Discussion, Social Groups (n = 48) |

| Mean (SD) Range | Mean (SD) Range | Mean (SD) Range | |

| Satisfaction (Mean Percentile Rank) | 58.46 (30.33) | 49.02 (26.98) | 48.92 (27.53) |

| Age | 56.77 (11.30) 36.05–73.52 | 56.62 (11.74) 27.30–85.28 | 56.13 (9.88) 28.91–77.06 |

| Months in group | 27.80 (15.32) 3.48–55.49 | 12.82 (16.95) 0.10–120.60 | 54.96 (53.42) 1.5–473.07 |

| Years from original diagnosis | 7.85 (3.27) 1.36–13.1 | 2.71 (4.55) 0.16–37.69 | 5.36 (4.77) 0.14–29.00 |

| Subscale | 1 (N) | 2 (N) | 3 (N) | 4 (N) | 5 (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Expressing True Feelings | 0.55 (102) 0.66 (220) | ||||

| 2. Discussing Sexual Concerns (single item) | 0.32 (223) | 0.64 (102) | |||

| 3. Developing a New Attitude | 0.56 (227) | 0.45 (223) | 0.51 (102) 0.76 (216) | ||

| 4. Accessing Resources and Advice | 0.26 (227) | 0.10 (223) | 0.35 (227) | 0.55 (102) 0.75 (224) | |

| 5. Establishing Supportive Contact | 0.54 (226) | 0.38 (223) | 0.63 (226) | 0.35 (226) | 0.64 (102) 0.84 (209) |

| 6. Satisfaction | 0.25 (207) | 0.16 (204) | 0.21 (208) | 0.07 (207) | 0.31 (206) |

| Mean Percentile Rank of Subscale | Therapist-Led | Non-Therapist-Led | p Value, d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford SET | TWC/CSC | |||

| (n = 20) | (n = 228) | (n = 48) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Expressing True Feelings | 59.56 (29.24) | 53.49 (27.51) | 30.54 (26.50) | 0.001 |

| SET vs. TWC/CSC | 0.64 a, 00.21 | |||

| SET vs. NTL | 0.001 b, 1.04 | |||

| TWC/CSC vs. NTL | 0.001 c, 0.85 | |||

| Discussing Sexual Concerns | 79.77 (19.81) | 51.98 (26.10) | 30.06 (26.55) | 0.001 |

| SET vs. TWC/CSC | 0.001 a, 1.20 | |||

| SET vs. NTL | 0.001 b, 2.12 | |||

| TWC/CSC vs. NTL | 0.001 c, 0.83 | |||

| Developing a New Attitude | 38.66 (27.79) | 53.61 (27.75) | 38.62 (30.35) | 0.001 |

| SET vs. TWC/CSC | 0.08 a, 0.65 | |||

| SET vs. NTL | 0.94 b, 0.09 | |||

| TWC/CSC vs. NTL | 0.02 c, 0.49 | |||

| Accessing Resources and Advice | 45.19 (28.72) | 52.10 (28.10) | 43.09 (30.20) | 0.10 |

| Establishing Supportive Contact | 50.97 (24.89) | 50.75 (28.70) | 47.15 (31.55) | 0.73 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giese-Davis, J.; Brandelli, Y.; Kronenwetter, C.; Golant, M.; Cordova, M.; Twirbutt, S.; Chang, V.; Kraemer, H.C.; Spiegel, D. Illustrating the Multi-Faceted Dimensions of Group Therapy and Support for Cancer Patients. Healthcare 2016, 4, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030048

Giese-Davis J, Brandelli Y, Kronenwetter C, Golant M, Cordova M, Twirbutt S, Chang V, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Illustrating the Multi-Faceted Dimensions of Group Therapy and Support for Cancer Patients. Healthcare. 2016; 4(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiese-Davis, Janine, Yvonne Brandelli, Carol Kronenwetter, Mitch Golant, Matthew Cordova, Suzanne Twirbutt, Vickie Chang, Helena C. Kraemer, and David Spiegel. 2016. "Illustrating the Multi-Faceted Dimensions of Group Therapy and Support for Cancer Patients" Healthcare 4, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030048

APA StyleGiese-Davis, J., Brandelli, Y., Kronenwetter, C., Golant, M., Cordova, M., Twirbutt, S., Chang, V., Kraemer, H. C., & Spiegel, D. (2016). Illustrating the Multi-Faceted Dimensions of Group Therapy and Support for Cancer Patients. Healthcare, 4(3), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030048