Generalization Task for Developing Social Problem-Solving Skills among Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Intervention: SCI-Labour Program

2.3. Target Measure: Social Problem-Solving Generalization Worksheet (ESCI-Generalization Task)

2.3.1. Procedure

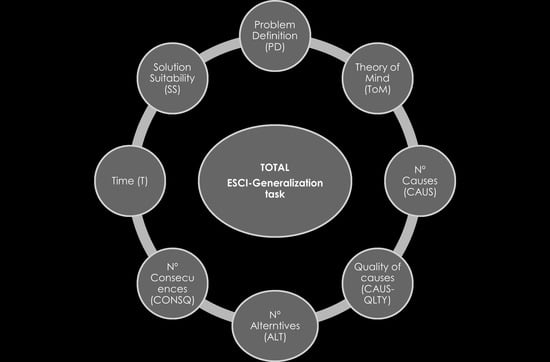

2.3.2. Response Coding

2.3.3. Coding Reliability

2.4. Statistic Design

3. Results

3.1. Differences between ASD Group Pre and Post-Treatment and Comparison Group

3.2. ASD Group Differences before and after Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stichter, J.P.; Herzog, M.J.; Visovsky, K.; Schmidt, C.; Randolph, J.; Schultz, T.; Gage, N. Social Competence Intervention for Youth with Asperger Syndrome and High-functioning Autism: An Initial Investigation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berenguer-Forner, C.; Miranda-Casas, A.; Pastor-Cerezuela, G.; Rosello-Miranda, R. Comorbidity of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit with hyperactivity. A review study. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 60, S37–S43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bowler, D.M. Theory of Mind in Asperger’s Syndrome Dermot M. Bowler. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1992, 33, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, D.P.; Adolphs, R. Perception of emotions from facial expressions in high-functioning adults with autism. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 3313–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, S.; Goddard, L.; Dritschel, B.; Wisley, M.; Howlin, P. Executive functions in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Brain Cogn. 2009, 71, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, A.; Fish, T.; Cloppert, P.; Beversdorf, D. Outcomes of a Social and Vocational Skills Support Group for Adolescents and Young Adults on the Autism Spectrum. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2007, 22, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symes, W.; Humphrey, N. Peer-group indicators of social inclusion among pupils with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools: A comparative study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2010, 31, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.; Holloway, J.; Lydon, H. An Evaluation of a Social Skills Intervention for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disabilities preparing for Employment in Ireland: A Pilot Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 48, 1727–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.W.S.; Leung, C.N.W.; Ng, D.C.Y.; Yau, S.S.W. Validating a Culturally-sensitive Social Competence Training Programme for Adolescents with ASD in a Chinese Context: An Initial Investigation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 48, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, J.A.; Kang, E.; Lerner, M.D. Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 52, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, C.; Odom, S.L.; Hume, K.; Cox, A.W.; Fettig, A.; Kucharczyk, S.; Schultz, T.R. Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder; The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group: Chapel Hill, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A.P. Social skills training. In Response to Aggression: Methods of Control and Prosocial Alternatives; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 159–218. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla, T.J.; Goldfried, M.R. Problem solving and behavior modification. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1971, 78, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppner, P.P.; Krauskopf, C.J. An Information-Processing Approach to Personal Problem Solving. Couns. Psychol. 1987, 15, 371–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, M.D.; García-Martín, M.B.; Bonete, S. Programa de entrenamiento en habilidades de resolución de problemas inter-personales para niños. In ESCI: Solución de Conflictos Interpersonales; García-Martín, M.B., Calero, M.D., Eds.; Manual Moderno: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pelechano, V. Inteligencia social y habilidades interpersonales [Social Intelligence and Interpersonal Skills]. Análisis Y Modif. Conducta 1984, 10, 393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Aldao, A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.L.; Wilkins, J. A critical review of assessment targets and methods for social skills excesses and deficits for children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2007, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrel, K.W. Assessment of Children’s Social Skills: Recent Developments, Best Practices, and New Directions. Except. A Spec. Educ. J. 2001, 9, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Constable, P.A.; Ring, M.; Gaigg, S.B.; Bowler, D.M. Problem-solving styles in autism spectrum disorder and the development of higher cognitive functions. Autism 2017, 22, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, C.; Bonete, S.; Gómez-Pérez, M.M.; Calero, M.D. Estudio normativo del “Test de 60 caras de Ekman” para adolescentes españoles. Psicol. Conduct. 2015, 23, 361. [Google Scholar]

- Bonete, S.; Calero, M.D.; Fernández-Parra, A. Group training in interpersonal problem-solving skills for workplace adaptation of adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome: A preliminary study. Autism 2014, 19, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.; Scarpa, A.; Conner, C.M.; Maddox, B.B.; Bonete, S. Evaluating Change in Social Skills in High-Functioning Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder Using a Laboratory-Based Observational Measure. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2014, 30, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buon, M.; Dupoux, E.; Jacob, P.; Chaste, P.; Leboyer, M.; Zalla, T. The Role of Causal and Intentional Judgments in Moral Reasoning in Individuals with High Functioning Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 43, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderborght, B.; Simut, R.; Saldien, J.; Pop, C.B.; Rusu, A.S.; Pintea, S.; Lefeber, D.; David, D.O. Using the social robot probo as a social story telling agent for children with ASD. Interact. Stud. 2012, 13, 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Brown, L.M.; Perry, T.D.; Dichter, G.S.; Bodfish, J.W.; Penn, D.L. Brief report: Feasibility fo social cognition and interaction training for adults with high functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goddard, L.; Howlin, P.; Dritschel, B.; Patel, T. Autobiographical Memory and Social Problem-solving in Asperger Syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 37, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Channon, S.; Charman, T.; Heap, J.; Crawford, S.; Rios, P. Real-life-type problem-solving in Asperger’s syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, R.; Lee, D. Promoting generalization and maintenance in augmentative and alternative communication: A meta-analysis of 20 years of effectiveness research. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2000, 16, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, T.F.; Baer, D.M. An implicit technology of generalization1. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1977, 10, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Froehlich, A.; Anderson, J.; Bigler, E.; Miller, J.; Lange, N.; DuBray, M.; Cooperrider, J.; Cariello, A.; Nielsen, J.; Lainhart, J. Intact prototype formation but impaired generalization in autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Golan, O.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.J. Mind Reading: The Interactive Guide to Emotions; London Jessica Kingsley Limited: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.A.; Beidel, D.C.; Murray, M.J. Social Skills Interventions for Children with Asperger’s Syndrome or High-Functioning Autism: A Review and Recommendations. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 38, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonete, S.; Molinero, C. The interpersonal problem-solving process: Assessment and intervention. In Newton, K. Problem-Solving: Strategies, Challenges and Outcomes; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Antshel, K.M.; Polacek, C.; McMahon, M.; Dygert, K.; Spenceley, L.; Dygert, L.; Miller, L.; Faisal, F. Comorbid ADHD and anxiety affect social skills group intervention treatment efficacy in children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2011, 32, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Kamphaus, R.W. Reynolds Intelectual Assessment Scales (RIAS); PAR: Odessa, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Hus, V.; Lord, C. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Encycl. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2013, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Risi, S.; Lambrecht, L.; Cook, E.H., Jr.; Leventhal, B.L.; DiLavore, P.C.; Pickles, A.; Rutter, M. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 30, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradiz, V. The Integrated Self-Advocacy ISA Curriculum: A Program for Emerging Self-Advocates with Autism Spectrum and Other Conditions; Autism Asperger Publishing Co.: Overland Park, KS, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neely, L.C.; Ganz, J.B.; Davis, J.L.; Boles, M.B.; Hong, E.R.; Ninci, J.; Gillliland, W.D. Generalization and maintenance of functional living skills for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 3, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.M.; Spivack, G. Problem-solving therapy: The description of a new program for chronic psychiatric patients. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 1976, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shure, M.B.; Spivack, G. Interpersonal problem-solving in young children: A cognitive approach to prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1982, 10, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauminger, N. The Facilitation of Social-Emotional Understanding and Social Interaction in High-Functioning Children with Autism: Intervention Outcomes. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channon, S.; Crawford, S.; Orlowska, D.; Parikh, N.; Thoma, P. Mentalising and social problem solving in adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 19, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauminger, N.; Shulman, C.; Agam, G. Peer interaction and loneliness in high-functioning children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2003, 33, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugeson, E.A.; Frankel, F.; Gantman, A.; Dillon, A.R.; Mogil, C. Evidence-based social skills training for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The UCLA PEERS program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Truax, P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Watson, S.; McConnell, F.; Manola, E.; McConachie, H. Interventions based on the Theory of Mind cognitive model for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD008785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Jolliffe, T.; Mortimore, C.; Robertson, M. Another Advanced Test of Theory of Mind: Evidence from Very High Functioning Adults with Autism or Asperger Syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Estes, A.; Munson, J.; Rogers, S.J.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; Dawson, G. Long-Term Outcomes of Early Intervention in 6-Year-Old Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 54, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bottema-Beutel, K.; Park, H.; Kim, S.Y. Commentary on Social Skills Training Curricula for Individuals with ASD: Social Interaction, Authenticity, and Stigma. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 48, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottema-Beutel, K.; Turiel, E.; DeWitt, M.N.; Wolfberg, P.J. To include or not to include: Evaluations and reasoning about the failure to include peers with autism spectrum disorder in elementary students. Autism 2017, 21, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonete, S. Impacto del Entrenamiento de Habilidades Interpersonales Para la Adaptación Laboral en Jóvenes con Síndrome de Asperger. Doctoral Thesis, The University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Task |

|---|---|

| Session 2 | There was no generalization task for homework |

| Session 3 * | Carlos has left home late in the morning and has missed the bus, so he will arrive late to work. When he arrives to the office, he sees that his supervisor looks angry. |

| Session 4 | Pedro has been working in a library for two weeks. The first days, the manager explained to him all the tasks that he had to do. Among them was to send the letters that the manager always left sealed on top of the table. Today, Pedro found five letters with the address written on them and prepared to send, but they are open. The manager had left, so Pedro decided to send them anyways. When the manager arrived and realized, he becomes very angry and told him off because the letters were for important people and they were incomplete, he shouldn’t have sent them. Pedro is very sad; he thinks that his boss has no reason to be angry like this. |

| Session 5 | German works for a company, every employee works at their desk. Today, German takes a cup of coffee over to the boss’ desk. When he gives it to him, his hand trembles and the coffee falls onto his boss computer keyboard. The boss draws back abruptly, German can see the discomfort in his boss’ face.” |

| Session 6 | Sonia works as a doorman for the cultural center for her neighbourhood. The manager of the cultural center has asked her to write up a document with the detailed timetable of the center’s activities. It took two days to finish it and she is very proud of how it looks with very pretty colors and writing. However, when she shows it to the manager, he tells her seriously that he doesn’t like how it’s done, and she will have to it all over. |

| Session 7 | Julia works restocking a supermarket. Alongside her colleague, she makes sure all is done in the “Home” section. But her colleague, who has been working for the company longer than she has, most times isn’t very careful about placing the price labels, making the work slower and making it difficult for Julia to find what is missing. |

| Session 8 | Felipe has been working as an electrician in a company for a short time. The boss askes him every day to stay a little longer after he finishes his shift. This is starting to become a problem for Felipe. |

| Session 9 | Patricia works as a secretary. She has all documents filed in alphabetic order, but her boss doesn’t like how it’s done, and asks her to do it in a way that seems absurd to her. |

| Session 10 * | Jacinto is a security guard. He has finished his shift, but his supervisor, who is the one who must substitute him, hasn’t arrived. |

| Categories | Description |

|---|---|

| Problem Definition (PD) | Indicating if the problem was clearly stated (2 points), vaguely understood (1 point), or not understood at all (0 points). Maximum score: 2 |

| Theory of Mind (ToM) | Score based on the understanding of emotions (1 point) and thoughts (1 point) about the principal actor and the other person involved. Maximum score: 4 |

| Number of Causes (CAUS) | Number of causes attributed to the problem. 1 point was given for every plausible cause, relevant to the situation. Maximum score: 10 |

| Quality of Causes (CAUS-QLTY) | The causes listed were categorized into “proximal” (refers to a cause with a recent effect) or “distant” (refers to a cause with a delayed effect). For coding, when a proximal and a distant cause are selected, the maximum score is given; if only a proximal or distant cause is selected, 1 point is given. Maximum score: 2 |

| Number of Alternatives (ALT) | Participants were asked to list possible actions (plausible and relevant) for the principal actors to solve the scenario. Each plausible and relevant solution scores 1 point. Maximum score: 8 |

| Quality of Alternatives (ALT-QLTY) | This score is the sum of four different subdomains exploring different aspects of the provided alternatives. A maximum of 8 for each of the 7 possible alternatives. Maximum score: 56 Activity (ACT): A solution is considered active if the main actor actually executes (2 points), but it is passive if action means to solve the problem through a third party not directly involved in the social problem (1 point). Relevancy (RELV): This scores if the action directly solves the issue (2 points) or is a step in a sequence of actions, indirectly solving the problem (1 point). Perspective (PERSP): 2 points if the participant took the other person involved into perspective and considered them affected by the action. Quality of Action (A-QLTY): 2 points when the action showed social sensitivity (coded in PERSP), and practical effectiveness (coded in RELV) |

| Number of Consequences (CONSQ) | Participants were required to list consequences to each alternative action that were plausible and relevant to the situation. 1 point for each option. Maximum score: 8 |

| Time (T) | This task measured whether participants consider the duration of the consequence. This task was measured by whether it had short- (ST) or long-term (LG) consequences. 2 points for each option if both types of consequence were considered up to 8 consequences. Maximum score: 16 |

| Solution Suitability (SS) | From the list of alternative actions, participants were to select the most appropriate and socially adequate actions regarding the situation. Maximum score: 2 |

| Total ESCI-Generalization Task | With the sum of the responses of the subject in the previous dimensions, this task provides a total score. Maximum score: 108 |

| Variables | Pre-ASD Group N (37) | CG N (48) | χ2 | p | r | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (df = 2) | ||||||||

| N (%) | Res | N (%) | Res | |||||

| PD | Incorrect | 5 (13.5%) | 2.8 * | 0 (0%) | −2.8 * | 17.41 | 0.000 | 0.45 |

| Partial | 28 (75.7%) | 4.9 * | 25 (52.1%) | −4.9 * | ||||

| Complete | 4 (10.8%) | −7.8 * | 23 (47.9%) | 7.8 * | ||||

| CAUS-QLTY | Incorrect | 12 (32.4%) | 4.6 * | 5 (10.4%) | −4.6 * | 27.96 | 0.000 | 0.57 |

| Partial | 22 (59.5%) | 7.2 * | 12 (25%) | −7.2 * | ||||

| Complete | 3 (8.1%) | −11.8 * | 31 (64.6%) | 11.8 * | ||||

| SS | Incorrect | 23 (62.2%) | 10.8 * | 5 (10.4%) | −10.8 * | 30.21 | 0.000 | 0.60 |

| Partial | 7 (18.9%) | 0.9 | 7 (14.6%) | −0.9 | ||||

| Complete | 7 (18.9%) | −11.7 * | 36 (75%) | 11.7 * | ||||

| Variables | Post-ASD Group N (39) | CG N (48) | χ2 | p | r | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (df = 2) | ||||||||

| N (%) | Res | N (%) | Res | |||||

| PD | Incorrect | 5 (12.8%) | 2.8 * | 0 (0%) | −2.8 * | 16.38 | 0.000 | 0.43 |

| Partial | 6 (15.4%) | −7.9 * | 25 (52.1%) | 7.9 * | ||||

| Complete | 28 (71.8%) | 5.1 * | 23 (47.9%) | −5.1 * | ||||

| CAUS-QLTY | Incorrect | 18 (47.4%) | 7.8* | 5 (10.4%) | −7.8 * | 18.79 | 0.000 | 0.46 |

| Partial | 11 (28.9%) | 0.8 | 12 (25%) | −0.8 | ||||

| Complete | 9 (23.7%) | −8.7 * | 31 (64.6%) | 8.7 * | ||||

| SS | Incorrect | 14 (35.9%) | 5.5 * | 5 (10.4%) | −5.5 * | 8.32 | 0.016 | 0.31 |

| Partial | 5 (12.8%) | −0.4 | 7 (14.6%) | 0.4 | ||||

| Complete | 20 (51.3%) | −5.1 * | 36 (75%) | 5.1 * | ||||

| Variables | ASD Group N (37) | CG N (48) | U | z | r | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | M | DT | Md | M | DT | ||||

| ToM | |||||||||

| Pre | 2 | 2.67 | 0.97 | 2 | 2.62 | 0.89 | 865.5 | −0.22 | 0.02 |

| Post | 2 | 1.92 | 1.24 | 2 | 636.5 ** | −2.83 | 0.31 | ||

| Number of causes | |||||||||

| Pre | 1 | 1.27 | 1.36 | 3 | 3.04 | 2.19 | 436.5 *** | −4.07 | 0.44 |

| Post | 1 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 3 | 389.5 *** | −4.75 | 0.51 | ||

| Number of alternatives | |||||||||

| Pre | 2 | 2.19 | 1.70 | 4 | 4.02 | 1.31 | 360 *** | −4.76 | 0.52 |

| Post | 3 | 2.92 | 1.69 | 4 | 576 ** | −3.13 | 0.32 | ||

| Quality of alternatives | |||||||||

| Pre | 2 | 7.78 | 7.16 | 4 | 16.04 | 5.94 | 248.5 *** | −5.68 | 0.62 |

| Post | 10 | 9.51 | 6.85 | 15.5 | 447 *** | −4.18 | 0.45 | ||

| Number of consequences | |||||||||

| Pre | 7 | 2.10 | 1.95 | 15.5 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 351.5 *** | −4.83 | 0.52 |

| Post | 3 | 2.84 | 1.88 | 4 | 503.5 *** | −3.75 | 0.41 | ||

| Time | |||||||||

| Pre | 1 | 1.24 | 1.46 | 4 | 1.60 | 1.60 | 190.5 *** | −6.26 | 0.68 |

| Post | 2 | 2.28 | 1.99 | 4 | 433 *** | −4.36 | 0.47 | ||

| Total ESCI-Task | |||||||||

| Pre | 19 | 19.56 | 12.71 | 38.5 | 38.85 | 10.55 | 187 *** | −6.22 | 0.67 |

| Post | 23 | 21.27 | 14.50 | 38.5 | 355 *** | −5.48 | 0.59 | ||

| Variables | Pre-ASD Group N (37) | Post-ASD Group N (39) | χ2 | p | r | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Res | N (%) | Res | |||||

| PD | Incorrect | 5 (13.5%) | 0.1 | 5 (12.8%) | −0.1 | 32.20 | 0.000 | 0.65 |

| Partial | 28 (75.7%) | 11.4 * | 6 (15.4%) | −11.4 * | ||||

| Correct | 4 (10.8%) | −11.6 * | 28 (71.8%) | 11.6 | ||||

| CAUS-QLTY | Incorrect | 12 (32.4%) | −2.8 * | 18 (47.4%) | 2.8 | 7.85 | 0.020 | 0.32 |

| Partial | 22 (59.5%) | 5.7 * | 11 (28.9%) | −5.7 * | ||||

| Complete | 3 (8.1%) | −2.9 * | 9 (23.7%) | 2.9 * | ||||

| SS | Incorrect | 23 (62.2%) | 5 * | 14 (35.9%) | −5 * | 8.73 | 0.013 | 0.34 |

| Partial | 7 (18.9%) | 1.2 | 5 (12.8%) | −1.2 | ||||

| Complete | 7 (18.9%) | −6.1 * | 20 (51.3%) | 6.1 * | ||||

| Categories | Pre-ASD Group N (32) | Post-ASD Group N (32) | Z | r | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | M | DT | Md | M | DT | |||

| ToM | 2 | 2.69 | 0.93 | 2 | 1.84 | 1.32 | −3.34 ** | 0.38 |

| Number of causes | 1 | 1.21 | 1.43 | 1 | 1.09 | 1.17 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| Number of alternatives | 2 | 2.15 | 1.76 | 3 | 2.90 | 1.75 | −2.15 * | 0.24 |

| Quality of alternatives | 7 | 7.40 | 7.06 | 10 | 9.50 | 6.76 | −1.53 | 0.17 |

| Number of consequences | 2 | 2.19 | 2.04 | 3 | 2. 90 | 2.01 | −2.07 * | 0.23 |

| Time | 1 | 1.22 | 1.47 | 2 | 2.41 | 2.08 | −2.69 ** | 0.30 |

| Total ESCI-Task | 19 | 19.22 | 13.24 | 23 | 24.12 | 13.51 | −2.00 * | 0.10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonete, S.; Molinero, C.; Garrido-Zurita, A. Generalization Task for Developing Social Problem-Solving Skills among Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Children 2022, 9, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020166

Bonete S, Molinero C, Garrido-Zurita A. Generalization Task for Developing Social Problem-Solving Skills among Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Children. 2022; 9(2):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020166

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonete, Saray, Clara Molinero, and Adrián Garrido-Zurita. 2022. "Generalization Task for Developing Social Problem-Solving Skills among Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorder" Children 9, no. 2: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020166

APA StyleBonete, S., Molinero, C., & Garrido-Zurita, A. (2022). Generalization Task for Developing Social Problem-Solving Skills among Young People with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Children, 9(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020166