This Is My Baby Interview: An Adaptation to the Spanish Language and Culture

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Population and Sample

2.2.1. Sample, Sampling, and Scope of Study

2.2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Coding and Measurement Procedure

Coding Responses into Indices

“Pablo is a lovely child; I love watching him sleep […] although sometimes I feel sorry when I look at him” (positive tone at first, but hostile tone at the end) (assigned score 3).

“This girl is too good, you know, she does nothing, she is not awake much, she eats and sleeps, she is a bit boring. But I guess these kids are like that […] as they are slower” (sad tone and long sentences, with silences) (assigned score 1).

“I don’t know what I would do without him, although he’s not what I expected” (affectionate tone, looking at the baby and smiling) (assigned score 4).

“Well, yes, I miss him if I’m not with him, but, come on … not so much yet because he was only recently born and I haven’t had time to miss him” (pauses in his/her response, listlessness in tone) (assigned score 1).

“I will try to give her what she needs […], we will do what we can to help Marta and make her happy […] even if it means a change of plans in the family” (positive tone, with hope and enthusiasm, quick responses) (assigned score 4).

“Well, I don’t know how we can take care of a child like that, we are not prepared for that […] I don’t know how to do this” (speaks in the third person of the baby, as if he/she were not present, hesitant) (assigned score 1)

- I would like to begin by asking you to describe (child’s name). What is (his/her) personality like?

- If (child’s name) ever had to leave your care, how much would you miss (him/her)?

- How do you think your relationship with (child’s name) is affecting (him/her) right now?

- How do you think your relationship with (child’s name) will affect (him/her) in the long-term?

- What do you want for (child’s name) right now?

- What do you want for (child’s name) in the future?

- Is there anything about (child’s name) or your relationship that we have not touched on that you would like to tell me?

- I would like to end by asking a few basic questions about your experience as a parent:

- a.

- How many biological and/or adopted children do you have?

- b.

- How many biological and/or adopted children are currently living in your home?

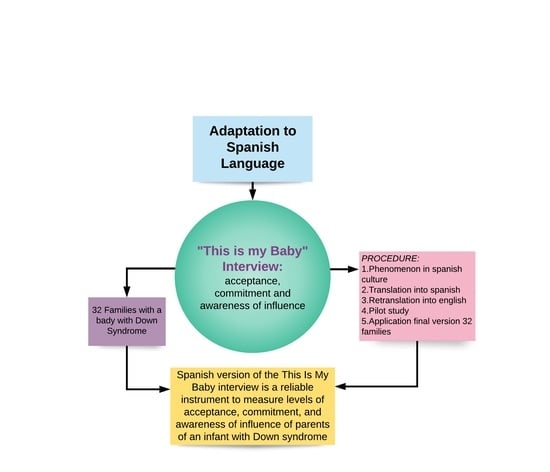

2.4. Procedure of Transcultural Adaptation to Spanish

- The phenomenon to be measured was found to exist in the Spanish culture. In this sense, the definitions of acceptance, commitment and awareness of influence in Spanish and English were verified in the scientific literature, proving that, regardless of the language, the concepts did not vary and apply to numerous contexts, especially in infant psychology, adoption and disability [14].

- The questionnaire was translated into Spanish and its conceptual equivalence was evaluated. The translation of the questionnaire was performed at two different time points, as the aim was for this translation to be rather conceptual than literal [27]. Two bilingual Spanish physiotherapists, who also knew the contents and purpose of the questionnaire, collaborated in this study, in order to prevent mistakes in the translation. From these translations, a meeting was held with the translators to agree upon the first Spanish version of the questionnaire. Subsequently, several experts in acceptance, commitment and awareness of influence evaluated the conceptual equivalence of this version with the original in English.

- The questionnaire was retranslated into English. Once the first translated version was obtained, it was sent separately to two native bilingual English translators who specialize in health science research papers and were unaware of the original questionnaire [27]. Subsequently, a meeting was held with the translators to verify that the retranslation did not differ conceptually from the original version and thereby validate the first translation into Spanish.

- A pilot study was carried out. This translated interview, which was considered as a draft, was submitted to a pilot study of ten fathers and mothers with babies with Down syndrome with the same characteristics as those of the families of the final sample. The aim of this pilot study was to identify confusing words or questions and to make sure that the interview questions were perfectly understandable to the mothers and fathers. During the application of this pilot study, the researchers were present to solve any doubts that the parents could have about the questions. In addition, the participants were asked to indicate those words or phrases that were confusing and give their opinion. Thus, the participants found the questions easy to understand. This did not imply any change in the wording of the questions, as no difficulties were found in the whole process of translation and retranslation. Due to the simple language used by the author of the original version, it was easy for the participants to read the questions in the study pilot. Consequently, it can be affirmed that the lexical conditions and comprehension of the items of the interview are suitable for its application.

- Application of the interview to 32 families with babies with Down syndrome using its final version. The pertinent statistical tests were carried out to assess the concordance of the different evaluations, the interpretation of the results, the ceiling and floor effect, and the internal consistency and sensitivity. A study was carried out with these parents, with the randomization of two groups using the sealed envelope system. Sixteen parents were assigned to a group that would receive massage therapy and the other sixteen were assigned to a control group that did not receive this intervention. This massage intervention consisted of five one-hour sessions, once per week, where the parents were taught the different infant massage maneuvers [4]. The allocation to the groups was done blindly and the interviewers were also blinded to the randomization of the groups. The evaluations and interviews were carried out by different people. The test–retest was performed with the 16 parents of the control group, who received no intervention. The scores assigned to the parents after the evaluations carried out by a second expert (expert 2) to measure the test–retest reliability were agreed upon with the families who answered; this allowed the former to check the score that was assigned to their answers, based on the tone of the conversation, the words used and the time to answer, among other aspects.

2.5. Data Collection for the Validation of TIMB Interview

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Concerning the Process of Choosing the Interview for Transcultural Translation and Adaptation

4.2. Concerning the Transcultural Translation and Adaptation Process

4.3. Concerning the Reliability of the TIMB Interview Adapted to the Spanish Language

4.3.1. Limitations

4.3.2. Future Research and Practical Relevance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’toole, C.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Gibbon, F.E.; van Bysterveldt, A.K.; Hart, N.J. Parent-mediated interventions for promoting communication and language development in young children with Down syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD012089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittingham, K.; Sheffield, J.; Mak, C.; Dickinson, C.; Boyd, R.N. Protocol: Early Parenting Acceptance and Commitment Therapy ‘Early PACT’ for parents of infants with cerebral palsy: A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Robles-Bello, M.A. Response to a resilience program applied to parents of children with Down syndrome. Univ. Psychol. 2015, 14, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinero-Pinto, E.; Benítez-Lugo, M.-L.; Chillón-Martínez, R.; Rebollo-Salas, M.; Bellido-Fernández, L.-M.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.-J. Effects of Massage Therapy on the Development of Babies Born with Down Syndrome. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 4912625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderkerken, L.; Heyvaert, M.; Onghena, P.; Maes, B. Family-centered practices in home-based support for families with children with an intellectual disability: Judgments of parents and professionals. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 25, 174462951989774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skotko, B.G.; Levine, S.P.; Goldstein, R. Having a son or daughter with Down syndrome: Perspectives from mothers and fathers. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 2335–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mas, J.M.; Dunst, C.J.; Balcells-Balcells, A.; Garcia-Ventura, S.; Giné, C.; Cañadas, M. Family-centered practices and the parental well-being of young children with disabilities and developmental delay. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 94, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooste, A.; Maes, B. Family Factors in the Early Development of Children with Down Syndrome. J. Early Interv. 2003, 25, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Nawi, A.; Ismail, A.; Abdullah, S. The impact on family among Down syndrome children with early intervention. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindensmith, R. Interventions to Improve Maternal-Infant Relationships in Mothers with Postpartum Mood Disorders. MCN Am. J. Matern. Nurs. 2018, 43, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porreca, A.; Parolin, M.; Bozza, G.; Freato, S.; Simonelli, A. Infant massage and quality of early mother-infant interactions: Are there associations with maternal psychological wellbeing, marital quality, and social support? Front. Psychol. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Moriyama, K.; Kaga, M.; Hiratani, M.; Watanabe, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Inagaki, M. Development and evaluation of a parenting resilience elements questionnaire (PREQ) measuring resiliency in rearing children with developmental disorders. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bourke, J.; Ricciardo, B.; Bebbington, A.; Aiberti, K.; Jacoby, P.; Dyke, P.; Msall, M.; Bower, C.; Leonard, H. Maternal physical and mental health in children with Down syndrome. J. Pediatr. 2008, 153, 320–326.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ter Kuile, H.; Finkenauer, C.; van der Lippe, T.; Kluwer, E.S. Changes in Relationship Commitment Across the Transition to Parenthood: Pre-pregnancy Happiness as a Protective Resource. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 622160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-González, L.; Lucena-Antón, D.; Salazar, A.; Martín-Valero, R.; Moral-Munoz, J.A. Physical therapy in Down syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 1041–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oppenheim, D.; Koren-Karie, N.; Dolev, S.; Yirmiya, N. Maternal insightfulness and resolution of the diagnosis are associated with secure attachment in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Driessen Mareeuw, F.A.; Coppus, A.M.W.; Delnoij, D.M.J.; de Vries, E. Quality of health care according to people with Down syndrome, their parents and support staff—A qualitative exploration. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagheri, F.; Nakhaee, N.; Jahani, Y.; Khajouei, R. Assessing parents’ awareness about children’s “first thousand days of life”: A descriptive and analytical study. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.Y.; Bornheimer, L.A.; Dankyi, E.; de-Graft Aikins, A. Parental Wellbeing, Parenting and Child Development in Ghanaian Families with Young Children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2018, 49, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente, S.; Veríssimo, M.; Diniz, E. Infant massage improves attitudes toward childbearing, maternal satisfaction and pleasure in parenting. Infant Behav. Dev. 2017, 49, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujnowska, A.M.; Rodríguez, C.; García, T.; Areces, D.; Marsh, N.V. Parenting and future anxiety: The impact of having a child with developmental disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bates, B.; Dozier, M. TIMB Interview. Coding Manual; University of Delaware: Newark, DE, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.; Canary, H.E.; McDougle, K.; Perkins, R.; Tadesse, R.; Holton, A.E. Family Sense-Making after a Down Syndrome Diagnosis. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1783–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fessler, M.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Brown, M. Caregiver Commitment to Foster Children: The Role of Child Behavior. Child Abus. Negl. 2007, 31, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dozier, M.; Stoval, K.C.; Albus, K.E.; Bates, B. Attachment for Infants in Foster Care: The Role of Caregiver State of Mind. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, K.; Dozier, M. This is my Baby: Foster parents’ feelings of commitment and displays of delight. Infant Ment. Health J. 2011, 32, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Argimón, J.M.; Jiménez, J. Métodos de Investigación Clínica y Epidemiológica; Elsevier: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consellería de Sanidade, Xunta de Galicia, España; Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS-OMS); Universidad CES. Epidat: Programa para Análisis Epidemiológico de Datos ; Versión 4.2; Universidad CES: Antioquia, Colombia, 2016; Available online: https://www.picuida.es/programa-estadistico-epidat-4-2-version-julio-2016/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Pardo Merino, A.; Ruiz Díaz, M.A. Análisis de varianza (I). ANOVA de un factor. In Análisis de Datos con SPSS 13 Base; McGraw-Hill/Interamericana De España: Madrid, Spain, 2005; p. 599. ISBN 9788448145361. [Google Scholar]

- Shoukri, M.M. Measures of Interobserver Agreement; Chapman & Hall/CRC.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stratford, P.W.; Goldsmith, C.H. Use of the standard error as a reliability index of interest: An applied example using elbow flexor strength data. Phys. Ther. 1997, 77, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin Bland, J.; Altman, D. Statistical Methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, 327, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, G.; Slattery, L.; Hudgins, L.; Ormond, K. Attitudes of Mothers of Children with Down Syndrome towards Noninvasive Prenatal Testing. J. Genet. Couns. 2014, 23, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Schendel, R.V.; Kater-Kuipers, A.; van Vliet-Lachotzki, E.H.; Dondorp, W.J.; Cornel, M.C.; Henneman, L. What Do Parents of Children with Down Syndrome Think about Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT)? J. Genet. Couns. 2017, 26, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crossman, M.K.; Warfield, M.E.; Kotelchuck, M.; Hauser-Cram, P.; Parish, S.L. Associations Between Early Intervention Home Visits, Family Relationships and Competence for Mothers of Children with Developmental Disabilities. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.C.; Iwamoto, V.E.; Latorre, M.; Dias de Oliveira Latorre, M.d.R.; Noronha, A.M.; de Sousa Oliveira, A.P.; Cardoso, C.E.A.; Marques, I.A.B.; Vendramim, P.; de Sant’Ana, T.H.S. Adaptação transcultural da Johns Hopkins Fall Risk Assessment Tool para avaliação do risco de quedas. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enfermagem 2016, 24, e2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q.; Schwandt, T.A. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods + the Sage Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781506303192. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Entering the field of qualititative research. In Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Robles Rodríguez, A.; Robles Rodríguez, J.; Giménez Fuentes-Guerra, F.J.; Abad Robles, M.T. Validación de una entrevista para estudiar el proceso formativo de judokas de élite/Validation of an Interview for Study the Process of Formation of Elite Judokas. Rev. Int. Med. Ciencias Act. Física Deport. 2016, 16, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parra de Quintero, M. Validación y aplicación de la entrevista semiestructurada codificada y observación a la idoneidad del profesor, en el Segundo año de Ciencias de la Salud. Rev. Educ. Cienc. Salud 2009, 6, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Trop, I.; Stolberg, H.O.; Nahmias, C. Estimates of diagnostic accuracy efficacy: How well can this test perform the classification task? Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2003, 54, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pita-Fernández, S.; Pértega-Díaz, S.; Maseda, E.R. La fiabilidad de las mediciones clínicas: El análisis de concordancia para variables numéricas. Cad. Aten. Primaria 2003, 10, 290–296. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptance | Words and content | Rejection or disgust when talking about the child | Negative maternal feelings | No positive or negative words, or mixed words | Relationship is positive | Describes relationship as very positive |

| Tone of conversation | Very hostile tone | Hostile tone | Medium | Positive tone | Very positive tone | |

| Time to give the answer | Very large | Large | Medium | Quick answer | Very quick answer | |

| Commitment | Words and content | Talks about the child as if he/she were not his/hers | Little feeling of belonging | Mixed words | Feelings of belonging | Obvious feelings of belonging |

| Tone of conversation | No efforts to form an affective bond | Little efforts to form an affective bond | Mixed tone during interview | Active efforts to form an affective bond | Very active efforts to form an affective bond | |

| Time to give the answer | Very large (too many pauses) | Large | Medium | Quick answer | Very quick answer | |

| Awareness of influence | Words and content | Does not show that he/she influences the baby | Some sign about his/her influence | Mixed content | Promotes the child’s sense of being loved or feeling secure | Promotes the development of age-appropriate psychological autonomy |

| Tone of conversation | Great hostile tone, speaking of the baby in the third person | Hostile tone | Mixed tone | Loving tone | Great loving tone, of affection | |

| Time to give the answer | Very large (too many pauses) | Large | Medium | Quick answer | Very quick answer | |

| Index | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | 1st–3rd Quartile | Range | Floor Effect (% Value 1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal investigator—1st measurement n = 32 | Acceptance | 2.172 | 0.921 | 2.0 | 1.250–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 25 |

| Commitment | 2.453 | 0.836 | 2.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 9.4 | |

| Awareness of influence | 2.688 | 0.849 | 3.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.50 | 3.1 | |

| Principal investigator–2nd measurement n = 32 | Acceptance | 2.203 | 1.007 | 2.0 | 1.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 28.1 |

| Commitment | 2.375 | 0.852 | 2.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 9,4 | |

| Awareness of influence | 2.563 | 0.849 | 2.5 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 9.4 | |

| Expert test n = 32 | Acceptance | 2.188 | 1.045 | 2.0 | 1.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.50 | 28.1 |

| Commitment | 2.422 | 0.993 | 2.0 | 1.750–3.0 | 1.0–4.50 | 9.4 | |

| Awareness of influence | 2.578 | 0.881 | 3.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 9.4 | |

| Expert test n = 16 | Acceptance | 2.188 | 1.047 | 2.0 | 1.250–2.750 | 1.0–4.50 | 25.0 |

| Commitment | 2.438 | 0.947 | 2.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.50 | 6.3 | |

| Awareness of influence | 2.531 | 0.921 | 3.0 | 1.750–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 12.5 | |

| Expert retest n = 16 | Acceptance | 2.250 | 1.032 | 2.0 | 1.250–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 12.5 |

| Commitment | 2.531 | 0.763 | 2.25 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.5–4.0 | 3.1 | |

| Awareness of influence | 2.594 | 0.800 | 2.75 | 2.0–3.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 3.1 |

| Index | ICC | p-Value | SEM | MDC | Weighted Kappa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal investigator—1st measurement Principal investigator—2nd measurement n = 32 | Acceptance | 0.950 | <0.001 | 0.219 | 0.607 | 0.824 |

| Commitment | 0.962 | <0.001 | 0.158 | 0.438 | 0.878 | |

| Awareness of influence | 0.946 | <0.001 | 0.179 | 0.496 | 0.832 | |

| Principal investigator—1st measurement Expert test n = 32 | Acceptance | 0.915 | <0.001 | 0.291 | 0.807 | 0.753 |

| Commitment | 0.879 | <0.001 | 0.322 | 0.894 | 0.688 | |

| Awareness of influence | 0.912 | <0.001 | 0.249 | 0.690 | 0.723 | |

| Principal investigator—2nd measurement Expert test n = 32 | Acceptance | 0.929 | <0.001 | 0.276 | 0.765 | 0.820 |

| Commitment | 0.867 | <0.001 | 0.341 | 0.944 | 0.673 | |

| Awareness of influence | 0.932 | <0.001 | 0.228 | 0.632 | 0.820 | |

| Expert test-retest n = 16 | Acceptance | 0.898 | <0.001 | 0.646 | 1.792 | 0.777 |

| Commitment | 0.841 | <0.001 | 0.657 | 1.821 | 0.688 | |

| Awareness of influence | 0.895 | <0.001 | 0.544 | 1.507 | 0.733 |

| Comparison | Difference in the Index | Mean | Confidence Interval at 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit/Upper Limit | |||

| Principal investigator—1st measurement Principal investigator—2nd measurement n = 32 | Acceptance | −0.0313 | −0.1428/0.0803 |

| Commitment | 0.0781 | −0.0026/0.1589 | |

| Awareness of influence | 0.1250 | 0.0334/0.2166 | |

| Principal investigator—1st measurement Expert n = 32 | Acceptance | −0.0156 | −0.1639/0.1326 |

| Commitment | 0.0313 | −0.1334/0.1959 | |

| Awareness of influence | 0.1094 | −0.0180/0.2367 | |

| Principal investigator—2nd measurement Expert n = 32 | Acceptance | 0.0156 | −0.1254/0.1566 |

| Commitment | −0.0469 | −0.2204/0.1266 | |

| Awareness of influence | −0.0156 | −0.1322/0.1010 | |

| Expert test-retest n = 16 | Acceptance | −0.0625 | −0.3176/0.1926 |

| Commitment | −0.0938 | −0.3551/0.1676 | |

| Awareness of influence | −0.0625 | −0.2773/0.1523 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinero-Pinto, E.; Benítez-Lugo, M.-L.; Chillón-Martínez, R.; Escobio-Prieto, I.; Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.-J. This Is My Baby Interview: An Adaptation to the Spanish Language and Culture. Children 2022, 9, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020235

Pinero-Pinto E, Benítez-Lugo M-L, Chillón-Martínez R, Escobio-Prieto I, Chamorro-Moriana G, Jiménez-Rejano J-J. This Is My Baby Interview: An Adaptation to the Spanish Language and Culture. Children. 2022; 9(2):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020235

Chicago/Turabian StylePinero-Pinto, Elena, María-Luisa Benítez-Lugo, Raquel Chillón-Martínez, Isabel Escobio-Prieto, Gema Chamorro-Moriana, and José-Jesús Jiménez-Rejano. 2022. "This Is My Baby Interview: An Adaptation to the Spanish Language and Culture" Children 9, no. 2: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020235

APA StylePinero-Pinto, E., Benítez-Lugo, M. -L., Chillón-Martínez, R., Escobio-Prieto, I., Chamorro-Moriana, G., & Jiménez-Rejano, J. -J. (2022). This Is My Baby Interview: An Adaptation to the Spanish Language and Culture. Children, 9(2), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020235