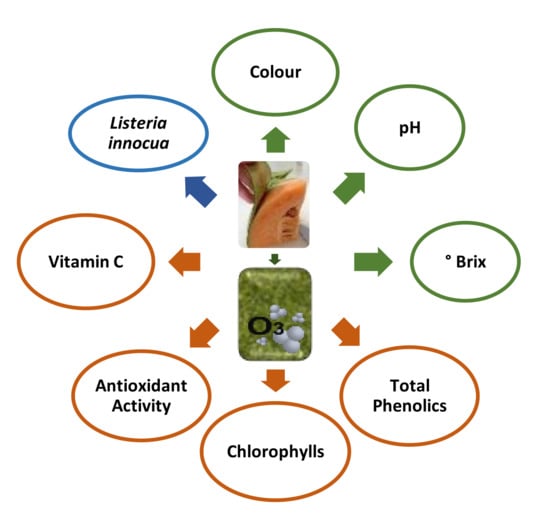

Effect of Gaseous Ozone Process on Cantaloupe Melon Peel: Assessment of Quality and Antilisterial Indicators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Ozone Treatment

2.3. Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties

2.3.1. Soluble Solids Content and pH

2.3.2. Colour Properties

2.4. Bioactive Compounds Analysis

2.4.1. Total Phenolics

2.4.2. Vitamin C Determination

2.4.3. Chlorophylls Determination

2.5. Total Antioxidant Activity

2.6. Microbiological Analysis

2.6.1. Culture

2.6.2. Peel Inoculation and Microbial Enumeration

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Ozone Exposure on Physicochemical Parameters

3.2. Effect of Ozone Exposure on Bioactive Compounds

3.3. Effect of Ozone Exposure on Total Antioxidant Activity

3.4. Effect of Ozone Exposure on Listeria Innocua Inactivation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, F.; Li, S.; Li, H.-B.; Deng, G.-F.; Ling, W.-H.; Wu, S.; Xu, X.-R.; Chen, F. Antiproliferative activity of peels, pulps and seeds of 61 fruits. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatt, S.R.; Chander, R.; Sharma, A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of pomegranate peel extract improves the shelf life of chicken products. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes Crizel, T.; Jablonski, A.; de Oliveira Rios, A.; Rech, R.; Flôres, S.H. Dietary fiber from orange byproducts as a potential fat replacer. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 53, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajila, C.M.; Bhat, S.G.; Prasada Rao, U.J.S. Valuable components of raw and ripe peels from two Indian mango varieties. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundo, J.F.; Miller, F.A.; Garcia, E.; Santos, J.R.; Silva, C.L.M.; Brandão, T.R.S. Physicochemical characteristics, bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in juice, pulp, peel and seeds of Cantaloupe melon. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadre, M.A.; Yousef, A.E.; Kim, J.-G. Microbiological Aspects of Ozone Applications in Food: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel-Seydim, Z.B.; Greene, A.K.; Seydim, A.C. Use of ozone in the food industry. LWT 2004, 37, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma, M.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Allende, A.; Cantwell, M.; Suslow, T. Effect of gaseous ozone and hot water on microbial and sensory quality of cantaloupe and potential transference of Escherichia coli O157:H7 during cutting. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selma, M.V.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Cantwell, M.; Suslow, T. Reduction by gaseous ozone of Salmonella and microbial flora associated with fresh-cut cantaloupe. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolles, A.; Mayo, B.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. Phenotypic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua strains isolated from short-ripened cheeses. Food Microbiol. 2000, 17, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.A.; Fundo, J.F.; Silva, C.L.M.; Brandão, T.R.S. Physicochemical and Bioactive Compounds of ‘Cantaloupe’ Melon: Effect of Ozone Processing on Pulp and Seeds. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigge, G.O.; Hansmann, C.F.; Joubert, E. Effect of storage conditions, packaging material and metabisulphite treatment on the color of dehydrated green bell peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Food Qual. 2001, 24, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, S.; Dufour, J.P. Ascorbic, Dehydroascorbic and Isoascorbic Acid Simultaneous Determinations by Reverse Phase Ion Interaction HPLC. J. Food Sci. 1992, 57, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV-VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3.1–F4.3.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.A.; Gil, M.M.; Brandão, T.R.S.; Teixeira, P.; Silva, C.L.M. Sigmoidal thermal inactivation kinetics of Listeria innocua in broth: Influence of strain and growth phase. Food Control. 2009, 20, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.A.; Silva, C.L.M.; Brandão, T.R.S. A Review on Ozone-Based Treatments for Fruit and Vegetables Preservation. Food Eng. Rev. 2013, 5, 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.M.; Botía, P.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G. Influence of deficit irrigation timing on the fruit quality of grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Mac.). Food Chem. 2015, 175, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obando, J.; Fernández-Trujillo, J.P.; Martínez, J.A.; Alarcón, A.L.; Eduardo, I.; Arús, P.; Monforte, A.J. Identification of Melon Fruit Quality Quantitative Trait Loci Using Near-isogenic Lines. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 133, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundo, J.F.; Amaro, A.L.; Madureira, A.R.; Carvalho, A.; Feio, G.; Silva, C.L.M.; Quintas, M.A.C. Fresh-cut melon quality during storage: An NMR study of water transverse relaxation time. J. Food Eng. 2015, 167, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohn, R.A.G.; Mauch, C.R.; Morselli, T.B.G.A.; Rombaldi, C.V.; Barros, W.S.; Sorato, V. Physical and chemical characteristics of melon in organic farming. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2015, 19, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drlange. Colour Review; Drlange Application Report No.8.0e; Drlange: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, D.A. Analysis of soft drinks and fruit juices. In Chemistry & Technology of Soft Drinks & Fruit Juices; Ashurst, P.R., Ed.; John Willey & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 231–289. [Google Scholar]

- Forney, C.F. Postharvest Response of Horticultural Products to Ozone. In Postharvest Oxidative Stress in Horticultural Crops; Hodges, D.M., Ed.; Food Products Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alothman, M.; Kaur, B.; Fazilah, A.; Bhat, R.; Karim, A.A. Ozone-induced changes of antioxidant capacity of fresh-cut tropical fruits. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, F.L.; Miller, J.E. Phenylpropanoid metabolism and phenolic composition of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] leaves following exposure to ozone. J. Exp. Bot. 1998, 49, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachadyn-Król, M.; Materska, M.; Chilczuk, B.; Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Perucka, I.; Jackowska, I. Ozone-induced changes in the content of bioactive compounds and enzyme activity during storage of pepper fruits. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Pelayo, R.; Gallardo-Guerrero, L.; Hornero-Méndez, D. Chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments in the peel and flesh of commercial apple fruit varieties. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weemaes, C.A.; Ooms, V.; Van Loey, A.M.; Hendrickx, M.E. Kinetics of Chlorophyll Degradation and Color Loss in Heated Broccoli Juice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 2404–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.M.S.; Vieira, M.C.; Silva, C.L.M. Modelling kinetics of watercress (Nasturtium officinale) colour changes due to heat and thermosonication treatments. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C.; Ríos, J.J.; Olías, R.; Olías, J.M. Effects of ozone treatment on postharvest strawberry quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1652–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinetta, V.; Vaidya, N.; Linton, R.; Morgan, M. A comparative study on the effectiveness of chlorine dioxide gas, ozone gas and e-beam irradiation treatments for inactivation of pathogens inoculated onto tomato, cantaloupe and lettuce seeds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 146, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, S.L.; Cash, J.N.; Siddiq, M.; Ryser, E.T. A Comparison of Different Chemical Sanitizers for Inactivating Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes in Solution and on Apples, Lettuce, Strawberries, and Cantaloupe. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peel | Colour Parameters | pH | SSC (°Brix) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | TCD | Chroma | Hue Angle (°) | |||

| Fresh | 45.46 ± 5.37 a | −12.70 ± 0.45 a | 31.71 ± 2.57 a | - | 34.19 ± 2.38 a | 111.99 ± 1.88 a | 5.90 ± 0.23 b | 6.21 ± 0.38 a |

| 30 min O3 | 39.15 ± 6.29 a | −12.71 ± 0.71 a | 28.66 ± 4.94 a | 8.79 ± 3.65 a | 31.43 ± 4.68 a | 114.58 ± 3.31 a | 5.64 ± 0.13 a,b | 6.67 ± 0.31 a |

| 60 min O3 | 41.91 ± 4.60 a | −12.57 ± 0.77 a | 29.53 ± 3.42 a | 5.46 ± 3.21 a | 32.15 ± 3.17 a | 113.39 ± 2.76 a | 5.10 ± 0.60 a | 6.48 ± 0.29 a |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miller, F.A.; Fundo, J.F.; Garcia, E.; Silva, C.L.M.; Brandão, T.R.S. Effect of Gaseous Ozone Process on Cantaloupe Melon Peel: Assessment of Quality and Antilisterial Indicators. Foods 2021, 10, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040727

Miller FA, Fundo JF, Garcia E, Silva CLM, Brandão TRS. Effect of Gaseous Ozone Process on Cantaloupe Melon Peel: Assessment of Quality and Antilisterial Indicators. Foods. 2021; 10(4):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040727

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiller, Fátima A., Joana F. Fundo, Ester Garcia, Cristina L. M. Silva, and Teresa R. S. Brandão. 2021. "Effect of Gaseous Ozone Process on Cantaloupe Melon Peel: Assessment of Quality and Antilisterial Indicators" Foods 10, no. 4: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040727

APA StyleMiller, F. A., Fundo, J. F., Garcia, E., Silva, C. L. M., & Brandão, T. R. S. (2021). Effect of Gaseous Ozone Process on Cantaloupe Melon Peel: Assessment of Quality and Antilisterial Indicators. Foods, 10(4), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040727