Natural Sources of Food Colorants as Potential Substitutes for Artificial Additives

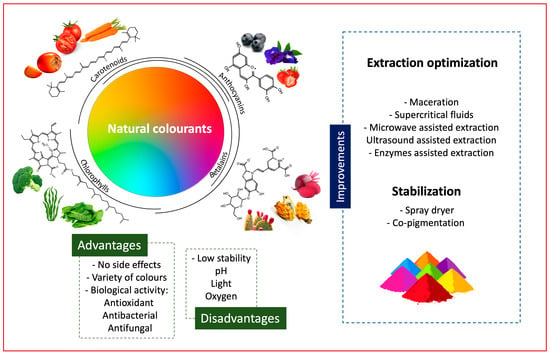

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Principal Colorant Compounds Found in Natural Matrices

2.1. Anthocyanins

2.2. Betalains

2.3. Carotenoids

2.4. Chlorophylls

3. Source of Natural Colorants as a Potential Replacers of Artificial Food Colorants

3.1. Source of Natural Red-Purple Colorants as a Potential Replacers of Artificial Colorants

| Pigment | Natural Source | Pigment Content of Extract | Extraction Conditions | Color Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red color | |||||

| Anthocyanins | Banana (Musa X paradisiaca L.) bracts | 32 mg of anthocyanins/100 g, being cyanidin-3-rutinoside the main anthocyanin (80%) | Maceration extraction: - solvent: 0.15% of HCl in methanol | Color parameters of extract: L*: 86.8, a*: 9.1 b*: 8.9 h: 44.2, C*: 12.7 | [49] |

| 2.45 mg of anthocyanins/100 g | Maceration extraction: - solvent: 1% of tartaric acid in water - s/L ratio: 5 g in 30 mL | - | [50] | ||

| 56.98 mg of anthocyanins/100 g | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - solvent: 53.97% ethanol in water - relation solvent/solute: 15/0.5 - temperature: 49.39 °C | Color parameters of encapsulated extract: L*: 61.38, a*: 21.53, b*: −0.08, h: 0.19, C*: 21.52 | [51] | ||

| 41.64 mg of anthocyanins/100 g of dietary fiber–anthocyanin formulation | Ultrasound-assisted extraction of anthocyanin: - solvent: 53.97% ethanol in water - relation solvent/solute: 15/0.5 - temperature: 49.39 °C | Color parameters of dietary fiber–anthocyanin formulation: L*: 50.42, a*: 9.12, b*: 8.14, h: 41.75, C*: 12.22 | [52] | ||

| Red onion (Allium atrorubens S. Watson) | 3.13 mg of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside equivalent/g, dw | Magnetic stirring at 600 rpm for 240 min: - solvent: 60% of glycerol and 13% of cyclodextrin in water - temperature: 80 °C - s/L ratio: 50 mL/g | - | [53] | |

| 21.99 mg of monomeric anthocyanin/L | Microwave: - extraction solvent: 75% ethanol in water - solvent feed ratio: 20 g/mL - time: 5 min - power: 700 W | - | [54] | ||

| Red calyces of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) | 51.76 mg of anthocyanins/g of extract | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - extraction solvent: 39.1% ethanol/water - time: 26.1 min - power: 296.6 W | - | [56] | |

| 1100–1700 mg of cyanidine-3-sambubioside equivalent/100 g | Solid–liquid extraction: - temperature: 35 °C and 75 °C - type of acid: acetic and citric - percentage of acid: 0.5 and 2.0% - time: 15 and 60 min - s/L ratio: 1/8 and 1/3 - water/ethanol ratio: 80/20 and 20/80 | - | [57] | ||

| 1308 mg of anthocyanins/100 g | Anthocyanin extract microencapsulated with yeast hulls | Color parameter of encapsulated extract: L*: 19.79, a*: 5.45, b*: 2.56, h: 0.97, C*: 6.02 | [58] | ||

| Red cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. Var. Capitata f. Rubra) | 390.6 mg of total anthocyanins/L | Extraction with 50% (v/v) of ethanol and acidified water: - s/L ratio: 1/2 - time: 1 min | Color parameters of extract: L*: 25.04, a*: 44.81, b*: 13.01, h: 16.18, C*: 46.67 | [60] | |

| 31.08 mg of anthocyanins/L | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - ethanol/water: 1/1 - power: 100 W - pulse mode: 300 s ON: 30 s OFF - temperature: 15 °C - time: 90 min | - | [61] | ||

| Purple or black carrot (Daucus carota L.) | 630.92 mg cyanidin-3-galactoside/100 g | Maceration extraction: - solvent: ethanol: 1.5 N HCl (85:15 v/v) - time: 8 min | Color parameters of microencapsulated powders: L*: 53.82, a*: 29.16, b*: 5.83, h: 11.31, C*: 29.74. | [65] | |

| 168.70 mg of anthocyanins/100 g, fw | Maceration extraction: - solvent: ethanol acidified with 0.01% citric acid. - s/L ratio: 20 g/100 mL - time: 5 min | - | [64] | ||

| Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) | 175.9 mg/g extract | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - solvent: hot water acidified (0.5% v/v acetic acid) (90 °C) followed by sonication: - amplitude: 100% -time: 5 min | - | [67] | |

| - | Anthocyanins with purity of 25% were purchased, then encapsulated with different combinations of carboxymethyl starch/xanthan gum | Color parameters of extract: L*: 43.94, a*: 0.68, b*: 1.76, h: 68.84, C*: 1.89 | [68] | ||

| 747.6 mg of cyanidin-3-glucoside/100 g, fw. | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - methanol 80% - sonicated for 20 min - room temperature | - | [70] | ||

| 371.5 mg cyanidin-3-glucoside/L | Crushed with juice press extractor | Color parameters of the extract encapsulated with maltodextrin (30 and 50%): L*: 54.2 and 52.7, a*: 36.6 and 38.0, b*: 1.4 and 2.9, h: 2.2 and 4.3, C*: 36.6 and 38.1, respectively. | [72] | ||

| Blackberry (Rubus spp.: Morus nigra L.; Rubus fruticosus L.) | 718.47 mg cyanidin 3-glucoside/100 g, fw | Maceration extraction: - s/L ratio: 1:3 (m/v) - temperature: room temperature - time 8 h - in absence of light | Color parameters of microencapsulated extract: L*: 34.34; a*: 20.96; b*: 6.51, h: 0.3, C*: 21.94 | [73] | |

| - 247 mg of cyanidin-3-glucoside/100 g (at pH 2.0) - 161 mg of cyanidin-3-glucoside/100 g (at pH 5.0) | Mechanical stirring extraction: - solvent: ethyl alcohol 80% - time: 48 h - rotavoparated at 65 °C - ratio: 500 mg/mL | - | [76] | ||

| Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) | 210.06 mg cyanidin-3-glucosido/ 100 g, fw | Freeze-dried and milled | Color parameters of the dry fruit: L*: 25.66, a*: 17.02, b*: 7.01, h: 22.39, C*: 18.41 | [110] | |

| Blackcurrant (Ribes Nigrum L.) | 900 mg of total anthocyanins/100 g of extract | Maceration extraction: - solvent: 0.1% HCl in methanol - time: 1 h | - | [80] | |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction: 2199 mg anthocyanin/100 g Enzyme-assisted extraction: 2164 mg anthocyanin/100 g | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - extraction solvent: 65% methanol in water - ratio s/L: 0.66 g/L - temperature: 5 °C - pH 4.97 Enzyme-assisted extraction: - extraction solvent: 10% ethanol in water - 50% of amplitude - 91.0 units of enzyme per gram - temperature: 30 °C - pH 4.1 | - | [81] | ||

| Haskap (Lonicera Caerulea L) | 2273 mg cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalents/100 g, dw | Ultrasound-assisted extraction optimized through RSM: - temperature: 35 °C - time: 20 min, - L/s rate: 4 mg/L - extraction solvent: 80% ethanol with 0.5% of formic acid | - | [83] | |

| Chokeberry fruits (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.) | 134 mg cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent/100 g, fw | Subcritical water extraction: - solvent: water and 1% citric acid - temperature: 190 °C - time: 1 min | - | [84] | |

| Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) | 4.67 mg cyanidin-3-gucloside/100 g, fw | The skin was freeze-dried and milled | Color parameters of the dry fruit: L*: 62.88, a*: 12.68, b*: 24.11, h: 62.26, C*: 27.24 | [110] | |

| Strawberry (Fragaria vesca L.) | 25.56 mg cyanidin-3-gucloside/100 g, fw | Freeze-dried and milled | Color parameters of the dry fruit: L*: 56.66, a*: 23.59, b*: 13.33, h: 29.47, C*: 27.09 | [110] | |

| Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna Jacq.) | 251.7 mg cyanidin-3-gucloside/100 g, dw | The skin was freeze-dried and milled | Color parameters of the dry skin: L*: 57.70, a*: 16.15, b*: 20.65 | [111] | |

| Whitebeam (Sorbus aria (L.) Crantz | 33.7 mg cyanidin-3-gucloside/100 g, dw | The skin was freeze-dried and milled | Color parameters of the dry skin: L*: 71.02, a*: 9.06, b*: 29.34 | [111] | |

| Black sorghum (Sorghum Moench) | - | Maceration extraction: - solvent: 1% of HCL in methanol - time: 2 h - s/L ratio: 0.1–0.5 g/25 mL | Color parameters of Sorghum kernels: L*: 34.2, a*: 3.8, b*: 2.8. | [88] | |

| Carotenoids: Lycopene | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) pulp | 2.08 mg lycopene/100 g, fw | High hydrostatic pressure-assisted extraction: - pressure: 450 MPa - solvent: 60% hexane | - | [92] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) peel | 13.592 mg all-trans-lycopene/100 g extract | Microwave-assisted extraction: - solvent: ethyl acetate - time: 1 min - microwave power: 400 W - energy: 24 kJ equivalent for 1 min | - | [93] | |

| Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) | 66.019–118.98 mg/kg, fw | Accelerated solvent extraction: - adjuvants: NaCl and paraffin oil - dehydrating agent: diatomaceous earth powder | - | [92] | |

| Guava (Psidium guajava L. cv. ‘Pedro Sato’) | 135.0 mg/100 g (extract from pulp); 76.64 mg/100 g (extract from waste) | Bath-type Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - solvent: ethyl acetate - frequency: 40 kHz - nominal power: 300 W - temperature: 25 °C - time: 30 min | - | [94] | |

| Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum & Nakai) | 1.092–4.81 μg/g | Maceration extraction: - solvent: methanol - time: 1 h - temperature: 30 °C | - | [95] | |

| Purple color | |||||

| Anthocyanins | Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) | 47 mg/100 g, fw | Subcritical water extraction: - solvent: water and 1% citric acid - temperature: 130 °C - time: 3 min | - | [84] |

| False shamrock leaves (Oxalis Triangularis S.-Hil) | 195 mg anthocyanins/100 g. | Maceration extraction: solvent: 0.15% HCl in methanol. | Color parameters (at pH 3.5): L*: 86.0, a*: 7.9 and b*: 1.4, h: 9.8, C*: 8.0 | [103] | |

| Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) skin | 45.01 mg of anthocyanins/100 g | Maceration extraction: - solvent: trifluoroacetic acid in water/acetone (30/70) - time: 60 min - ratio s/L: 1:2 | Better stability of color at pH 1 (L*: 65.83, C*: 52.12, h°: 8.92). | [104] | |

| 2410.71 mg cyanindin-3-glucoside/kg | Ultrasonic-assisted extraction: - solvent: 54.4% methanol - frequency: 37 kHz - temperature: 55.1 °C - time: 44.85 min | - | [105] | ||

| - | Maceration extraction: - solvent: distilled water - temperature: 80 °C - time: 40 min - ratio s/L: 5 g/100 mL | Color parameters of encapsulated extract: L*: 25.59, a*: 6.17, b*: 1.05, h: 9.66, C*: 6.26 | [106] | ||

| Black rice (Oryza sativa L.) bran | 948 mg of total anthocyanins/100 g | Enzymatic extraction. - 37 °C, pH: 7.5, protease, 30 min - 65 °C, pH: 6.9, α-amilasa, 60 min - 85 °C, 10 min | Color parameters: L*: 39.85, C*: 17.66, h: 12.60 | [109] | |

3.2. Source of Natural Pink Colorants as a Potential Replacers of Artificial Colorants

3.3. Source of Natural Yellow-Orange Colorants as a Potential Replacers of Artificial Colorants

| Pigment | Natural Source | Pigment Content in Extract | Extraction Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow–orange color | ||||

| Carotenoids | Red cashew apple (Anacardium Occidentale L.) | 154.9 µg of carotenoid/gram of orange extract | Ultrasound-assisted extraction compared with conventional extraction: - solvents: 25–100% of acetone, ethanol, petroleum ether, methanol - time: 20 min - mechanical shaking: 290 rpm Optimal conditions for ultrasonic-assisted extraction: 19 min of sonication and a mixture of 44% acetone and 56% methanol. | [125] |

| Palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) press fiber | 1140 mg β-carotene/100 g | Supercritical CO2 extraction: - temperature: 20–60 °C - pressure: 120–125 MPa Compressed liquefied petroleum gas (LPG): - temperature 20–40 °C - pressure: 0.5–2.5 MPa The higher amount of carotenoids (β-carotene) was obtained using LPG | [126] | |

| 253.9 mg of ß-carotene/100 g | Cold extraction - solvents: ethanol, isopropanol, hexane, cyclohexane, heptane - s/L ratio: 1:5 - time: 8 h The highest carotenoid content was obtained with the use of hexane | [127] | ||

| Gac fruit (Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng.) peel | 271 mg per 100 g, dw | Extraction through maceration: - solvents: acetone, ethanol, ethyl acetate, hexane - time: 90–150 min - temperature: 30–50 °C - s/L ratio: 10–80 mL/g Optimal conditions were with ethyl acetate at a solid–liquid ratio of 80 mL/g and 40.7 °C for 150 min | [128] | |

| 268 mg carotenoid/ 100 g, dw | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - power: 150, 200 and 250 W - frequency: 43.2 kHz - temperature: 20 °C Microwave-assisted extraction: - power: 120, 240 and 360 W - temperature: until reached 60 °C Higher yield of carotenoids was obtained with ultrasound-assisted extraction under conditions of 200 W and 80 min with ethyl acetate as solvent. | [129] | ||

| Strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) | 0.808 mg ß-carotene/100 g, fw | Maceration extraction: - solvent: hexane/acetone/ethanol 50:25:25 - magnetic stirring: 30 min | [131] | |

| Ripe bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) pericarp | 85.54 mg ß-carotene/100 g | Enzymatic treatment (load of 167 U/g) followed by supercritical fluid extraction: - pressure: 150–450 bar - CO2 flow rate: 15–55 mL/min - temperature: 50–90 °C - time: 45–225 min The optimal conditions for supercritical fluid extraction were 390 bar and 35 mL/min at 70 °C for 190 min | [130] | |

| Mango (Mangifera indica L.) peel | 1.9 mg all-trans-ß-carotene/g, dw | Supercritical fluid extraction with CO2: - temperature: 40–60 °C - pressure: 25–35 MPa - ethanol as co-solvent: 5–15%, w/w The optimal extraction conditions for the highest yields of carotenoids were 25.0 MPa, 60 °C and 15% w/w ethanol | [132] | |

| 5.6 mg of ß-carotene/g, dw | Supercritical CO2 extraction, followed by pressurized ethanol, both extractions methods at: - pressure: 30 MPa - temperature: 40 °C - ratio s/L: 3 g/10 mL A higher concentration of carotenoids was extracted with supercritical CO2 extraction | [133] | ||

| Rowanberry fruit (Sorbus aucuparia L.) | 19.14 mg carotenoids/g of extract | Consecutive extraction with supercritical CO2 followed by pressurized liquid extraction: Supercritical fluid extraction: - pressure: 25–45 MPa - temperature: 40–60 °C - flow rate of CO2: 2 SL/min - time: 180 min Pressurized liquid extraction: - temperature: 70 °C - pressure: 10.3 MPa - time: 15 min (3 cycles of 5 min of static extraction) The optimal extraction conditions with supercritical CO2, determined through RSM, were 45 MPa and 60 °C for 180 min. | [134] | |

| Persimmon fruits (Diospyros kaki L.) | 15.46, 16.81, and 33.23 µg/g (dw) for all-trans-lutein, all-trans-zeaxanthin, all-trans-ß-cryptoxanthin, respectively | Extraction with supercritical CO2 and ethanol as cosolvent: - temperature: 40–60 °C - pressure: 100–300 bars - ethanol %: 5–25 - CO2 flow rate: 1–3 mL/min - time: 30–100 min The best conditions were 300 bars, 60 °C, 25% (w/w) ethanol at a flow rate of 3 mL/min flow for 30 min | [135] | |

| 11.19 µg of all-trans-ß-carotene/g, dw | Supercritical CO2 extraction: - cosolvent: ethanol 25% (w/w) - pressure: 100 bars - temperature: 40 °C - flow: 1 mL/min - time: 30 min | [135] | ||

| 35.48–75.84 µg of carotenoids/100 g, fw | Ultrasound-assisted extraction: - s/L ratio: 2 g/50 mL - solvent: hexane:acetone:ethanol (50:25:25 v/v/v) - time: 10 min | [136] | ||

| betaxanthins | Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) | 11.37 mg betaxanthins/L/U | Enzymatic extraction, including the evaluation of the following parameters: - total dosage of the acetate buffer containing the multi-component enzymatic mix: 10–50 U/g - temperature: 25 or 45 °C - time: 0–5 h - pH: 5.5 - ratio s/L: 1/15 It was determined that 25 U/g of total dose enzymatic mix, 25 °C and 240 min were the best conditions | [110] |

| Cactus fruit (Opuntia ficus indica) | 32.3–72.4 mg of betaxanthins/kg of juice | Maceration extraction: - solvent: methanol - s/L ratio: 1:5 w/v - time: 1 min - magnetic stirring The betaxanthins were more stable at pH 3.5 with ascorbic acid | [137] | |

| Cactus fruit (Opuntia ficus indica) | 27.5 mg indicaxanthin/100 g | Extraction by homogenization with ultraturrax followed by centrifugation; the supernatant was determined as an extract rich in betaxanthin | [138] | |

| Pitahaya fruit peel (Hylocereus megalanthus (K.Schum. ex Vaupel)) | 0.1058 mg betaxanthin/g of sample | Maceration extraction: - solvent: ethanol/water (50/50 v/v) - s/L ratio: 10 g/300 mL - stirring: 700 rpm - temperature: room temperature - time: 5 h | [139] | |

3.4. Source of Natural Green Colorants as a Potential Replacers of Artificial Colorants

| Pigment | Natural Source | Pigment Content | Extraction Conditions | Optimal Extraction Conditions/Color Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green color | |||||

| Chlorophylls | Custard apple (Annona Squamosa L.) leaves | 1.38 mg of total chlorophylls/g (without the use of PEFs), and 0.35 mg of chlorophylls/ g (by using PEFs) | Pulsed electric fields extraction: - electric field strength: 6 kV/cm, - pulses: 300 - specific energy: 142 kJ/kg - time: 5 min | A better extraction of chlorophylls was evidenced without the use of pulsed electric fields than with it. | [145] |

| Broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) | - | High-intensity pulsed electric fields: - time: 500–2000 µs - electric field strength: 15–35 kV/cm - polarity: monopolar or bipolar - pulse width: 4 µs - frequency: 100 Hz | The optimal conditions, according to the color parameters (ΔE* of 2.11), were 26.35 kV/cm for 1.235 µs in bipolar mode. | [146] | |

| Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) | 20.75 µg of total chlorophyll/ mL of juice | Maceration extraction followed by pulsed electric fields treatment Maceration extraction (consecutive extraction): - solvent: absolute ethanol - ratio s/L: 200 g/ 400 mL - time: 30 min - centrifugation: 500 g for 10 min Pulsed electric fields treatment: - electric field intensity: 0–26.7 kV/cm - temperature: 20–45 °C | The best pulsed electric field conditions were 26 kV/cm of voltage, 35 °C and pulses width of 20 µs. | [147] | |

| 46.78 µg/ g of dry powder | Chlorophyll extract was dispersed in MCT oil to a concentration of 0.01 g/mL followed by stabilization by microencapsulation: - wall materials: maltodextrin, gum Arabic - intel air temperature: 145 °C - outlet temperature: 95 °C - pump speed: 1.5 mL/min | The best wall material was maltodextrin with color parameters of: L*: 26.22, a*: −16.72, b*: 19.64, h: 131.43, C*: 25.78. | [149] | ||

| Centella asiatica L. leaves | - | Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of the leaves after a treatment with zinc or copper for the generation of complexes: Ultrasonic-assisted extraction: - ratio s/L: 10 g/200 mL - time: 10 min - frequency: 37 kHz - power: 500 W | The untreated extract presented a light green color (L*: 40.17, a*: −11.13, h: 116.49), while the zinc and the copper-treated extracts presented a yellow–green color (L*: 21.43, a*: −6.95, h: 113.10). A better stability against acid pH and heat was evidenced in the extract treated with metals. | [148] | |

3.5. Source of Natural Blue Colorants as a Potential Replacement for Artificial Colorants

4. Incorporation of Natural Food Colorants in Food Matrix

4.1. Incorporation of Anthocyanins in Food Matrix

4.2. Incorporation of Betalains in Food Matrix

4.3. Incorporation of Carotenoids in Food Matrix

4.4. Incorporation of Chlorophylls in Food Matrix

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spence, C. On the Manipulation, and Meaning(s), of Color in Food: A Historical Perspective. J. Food Sci. 2022, 88, A5–A20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/overview-food-ingredients-additives-colors (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-colours (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/industry/color-additives/color-additives-history (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Feingold, B.F. Hyperkinesis and Learning Disabilities Linked to the Ingestion of Artificial Food Colors and Flavors. J. Learn. Disabil. 1976, 9, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, D.; Barrett, A.; Cooper, A.; Crumpler, D.; Dalen, L.; Grimshaw, K.; Kitchin, E.; Lok, K.; Porteous, L.; Prince, E.; et al. Food Additives and Hyperactive Behaviour in 3-Year-Old and 8/9-Year-Old Children in the Community: A Randomised, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, R.D.; Pollock, I.; Naeem, S. Tartrazine Induced Histamine Release in Vivo in Normal Subjects. J. R. Coll. Physicians 1987, 21, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo, G.; Pacor, M.L.; Vignola, A.M.; Profita, M.; Esposito-Pellitteri, M.; Biasi, D.; Corrocher, R.; Caruso, C. Urinary Metabolites of Histamine and Leukotrienes before and after Placebo-controlled Challenge with ASA and Food Additives in Chronic Urticaria Patients. Allergy 2002, 57, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, S.; Moreira, M.; Olej, B. Safety of Ingestion of Yellow Tartrazine by Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Challenge in 26 Atopic Adults. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2010, 38, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-W.; Park, C.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Park, J.Y.; Park, H.S.; Yang, H.J.; Ahn, K.-M.; Kim, K.-H.; Oh, J.-W.; Kim, K.-E.; et al. Dermatologic Adverse Reactions to 7 Common Food Additives in Patients with Allergic Diseases: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 1059–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, K.A.; Fawzia, S.A.-S. Toxicological and Safety Assessment of Tartrazine as a Synthetic Food Additive on Health Biomarkers: A Review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 17, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Ponceau 4R (E 124) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Sunset Yellow FCF (E 110) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Quinoline Yellow (E 104) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Statement on Allura Red AC and Other Sulphonated Mono Azo Dyes Authorised as Food and Feed Additives. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Color Additives and Behavioral Effects in Children. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/131378/download (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Leo, L.; Loong, C.; Ho, X.L.; Raman, M.F.B.; Suan, M.Y.T.; Loke, W.M. Occurrence of Azo Food Dyes and Their Effects on Cellular Inflammatory Responses. Nutrition 2018, 46, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, A.; Vojdani, C. Immune Reactivity to Food Coloring. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2015, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Al-Khalifa, A.S.; Al-Nouri, D.M.; El-din, M.F.S. Dietary Intake of Artificial Food Color Additives Containing Food Products by School-Going Children. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batada, A.; Jacobson, M.F. Prevalence of Artificial Food Colors in Grocery Store Products Marketed to Children. Clin. Pediatr. 2016, 55, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.J.; Burgess, J.R.; Stochelski, M.A.; Kuczek, T. Amounts of Artificial Food Dyes and Added Sugars in Foods and Sweets Commonly Consumed by Children. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 54, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdson, G.T.; Tang, P.; Giusti, M.M. Natural Colorants: Food Colorants from Natural Sources. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.-M.; Chia, L.-S.; Goh, N.-K.; Chia, T.-F.; Brouillard, R. Analysis and Biological Activities of Anthocyanins. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata, A.; López, C.; Tesfaye, W.; González, C.; Escott, C. Anthocyanins as Natural Pigments in Beverages. In Value-Added Ingredients and Enrichments of Beverages; Grumezescu, A.M., Holban, A.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 14, pp. 383–428. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, K.L.; Liu, R.H. Structure−Activity Relationships of Flavonoids in the Cellular Antioxidant Activity Assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 8404–8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, Ø.M.; Jordheim, M. Basic Anthocyanin Chemistry and Dietary Sources. In Anthocyanins in Health and Disease; Wallace, T.C., Giusti, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 13–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Celli, G.B.; Brooks, M.S. Natural Sources of Anthocyanins. In Anthocyanins from Natural Sources: Exploiting Targeted Delivery for Improved Health; Su-Ling, M., Celli, G.B., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Butelli, E.; Martin, C. Engineering Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 19, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and Anthocyanins: Colored Pigments as Food, Pharmaceutical Ingredients, and the Potential Health Benefits. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, N.; Roriz, C.L.; Morales, P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Coloring Attributes of Betalains: A Key Emphasis on Stability and Future Applications. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1357–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Biological Properties and Applications of Betalains. Molecules 2021, 26, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraja, T.; Joshi, A.; Sethi, S.; Kaur, C.; Tomar, B.S.; Varghese, E.; Dahuja, A. Stability Enhancement of Beetroot Betalains through Copigmentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 5561–5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as Natural Functional Pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas Santos, P.D.; Rubio, F.T.V.; da Silva, M.P.; Pinho, L.S.; Favaro-Trindade, C.S. Microencapsulation of Carotenoid-Rich Materials: A Review. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, M.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, F.; Liao, L. Stability of Carotenoids and Carotenoid Esters in Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) Slices during Hot Air Drying. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Galvez, A.; Viera, I.; Roca, M. Chemistry in the Bioactivity of Chlorophylls: An Overview. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 24, 4515–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, I.; Pérez-Gálvez, A.; Roca, M. Green Natural Colorants. Molecules 2019, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Chlorophylls (E 140(i)) as Food Additives. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Yañez, J.; Mojica, L.; Luna-Vital, D.A. Technological Applications of Natural Colorants in Food Systems: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamwonglumlert, L.; Devahastin, S.; Chiewchan, N. Natural Colorants: Pigment Stability and Extraction Yield Enhancement via Utilization of Appropriate Pretreatment and Extraction Methods. Crit Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3243–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. 21 CFR Part 73 (Up to Date as of 8/08/2023) Listing of Color Additives Exempt from Certification; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 231/2012 of 9 March 2012. Laying down Specifications for Food Additives Listed in Annexes II and III to Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Souza, C.; Bandoni, D.H.; Bragotto, A.P.A.; De Rosso, V.V. Risk Assessment of Azo Dyes as Food Additives: Revision and Discussion of Data Gaps toward Their Improvement. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Refined Exposure Assessment for Allura Red AC (E 129). EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Refined Exposure Assessment for Azorubine/Carmoisine (E 122). EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Refined Exposure Assessment for Ponceau 4R (E 124). EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commision. Commission Regulation (EU) N° 1129/2011 of 11 November 2011 Amending Annex II to Regulation (EC) N° 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing Union List of Food Additives; EU Commision: Luxembourg, 2011; pp. 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pazmiño-Durán, E.A.; Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E.; Glória, M.B.A. Anthocyanins from Banana Bracts (Musa X paradisiaca) as Potential Food Colorants. Food Chem. 2001, 73, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestario, N.L.; Catur Yoga, M.K.W.; Ignatius Kristijanto, A. Stabilitas Antosianin Jantung Pisang Kepok (Musa paradisiaca L.) Terhadap Cahaya Sebagai Pewarna Agar-Agar. J. Agritech. 2014, 34, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, Y.A.; Deka, S.C. Stability of Spray-Dried Microencapsulated Anthocyanins Extracted from Culinary Banana Bract. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 3135–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, Y.A.; Deka, S.C. Ultrasound-Assisted Extracted Dietary Fibre from Culinary Banana Bract as Matrices for Anthocyanin: Its Preparation, Characterization and Storage Stability. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzinos, I.; Prodromidis, P.; Grigorakis, S.; Makris, D.P.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Moschakis, T. Natural Food Colorants Derived from Onion Wastes: Application in a Yoghurt Product. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krithika, J.S.; Sathiyasree, B.; Beniz Theodore, E.; Chithiraikannu, R.; Gurushankar, K. Optimization of Extraction Parameters and Stabilization of Anthocyanin from Onion Peel. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2560–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, I.; Pereira, E.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C.; Soković, M.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. as a Source of Nutrients, Bioactive Compounds and Colouring Agents. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinela, J.; Prieto, M.A.; Pereira, E.; Jabeur, I.; Barreiro, M.F.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Optimization of Heat- and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Anthocyanins from Hibiscus sabdariffa Calyces for Natural Food Colorants. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Ortiz, A.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Rocha-Guzmán, N.E.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Reynoso-Camacho, R. Anthocyanins Extraction from Hibiscus sabdariffa and Identification of Phenolic Compounds Associated with Their Stability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.-T.; Voilley, A.; Tran, T.T.T.; Waché, Y. Microencapsulation of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Calyx Anthocyanins with Yeast Hulls. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghareaghajlou, N.; Hallaj-Nezhadi, S.; Ghasempour, Z. Red Cabbage Anthocyanins: Stability, Extraction, Biological Activities and Applications in Food Systems. Food Chem. 2021, 365, 130482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, J.; Madhusudhan, M.C.; Raghavarao, K.S.M.S. Extraction of Anthocyanins from Red Cabbage and Purification Using Adsorption. Food Bioprod. Process 2012, 90, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanfar, R.; Moein, M.; Niakousari, M.; Tamaddon, A. Extraction and Fractionation of Anthocyanins from Red Cabbage: Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction and Conventional Percolation Method. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 2271–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.H.; da Rosa Almeida, A.; de Oliveira Brisola Maciel, M.V.; Vitorino, V.B.; Bazzo, G.C.; da Rosa, C.G.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Mendes, C.; Barreto, P.L.M. Microencapsulation by Spray Drying of Red Cabbage Anthocyanin-Rich Extract for the Production of a Natural Food Colorant. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Encapsulation of Red Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea L. var.capitata L. f. Rubra) Anthocyanins by Spray Drying Using Different Encapsulating Agents. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2015, 58, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assous, M.T.M.; Abdel-Hady, M.M.; Medany, G.M. Evaluation of Red Pigment Extracted from Purple Carrots and Its Utilization as Antioxidant and Natural Food Colorants. Ann. Agri. Sci. 2014, 59, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersus, S.; Yurdagel, U. Microencapsulation of Anthocyanin Pigments of Black Carrot (Daucus carota L.) by Spray Drier. J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Morales, P.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, B.M.; Isasa, E.T. Nutrients and Bioactive Compounds in Wild Fruits Through Different Continents. In Wild Plants, Mushrooms and Nuts; Ferreira, C.F.R., Morales, P., Barros, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 263–314. [Google Scholar]

- Buran, T.J.; Sandhu, A.K.; Li, Z.; Rock, C.R.; Yang, W.W.; Gu, L. Adsorption/Desorption Characteristics and Separation of Anthocyanins and Polyphenols from Blueberries Using Macroporous Adsorbent Resins. J. Food Eng. 2014, 128, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Du, X.; Cui, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, G. Improvement of Stability of Blueberry Anthocyanins by Carboxymethyl Starch/Xanthan Gum Combinations Microencapsulation. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 91, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Ma, L.; Miao, S.; Hu, X.; Liao, X.; Chen, F.; Ji, J. The In-Vitro Digestion Behaviors of Milk Proteins Acting as Wall Materials in Spray-Dried Microparticles: Effects on the Release of Loaded Blueberry Anthocyanins. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 115, 106620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, G.A.; Soto, C.Y.; López-R, M.; Riedl, K.M.; Browmiller, C.R.; Howard, L. Phenolic Profile, in Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Antioxidant Capacity of Vaccinium Meridionale Swartz Pomace. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Padilla, A.; Ruiz-Rodriguez, A.; Restrepo Flórez, C.; Rivero Barrios, D.; Reglero, G.; Fornari, T. Vaccinium Meridionale Swartz Supercritical CO2 Extraction: Effect of Process Conditions and Scaling Up. Materials 2016, 9, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñan-Amaya, M.; Fuenmayor, C.A.; López-Córdoba, A. New Freeze-Dried Andean Blueberry Juice Powders for Potential Application as Functional Food Ingredients: Effect of Maltodextrin on Bioactive and Morphological Features. Molecules 2020, 25, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, C.; Chung, M.M.S.; dos Santos, C.; Mayer, C.R.M.; Moraes, I.C.F.; Branco, I.G. Microencapsulation of an Anthocyanin-Rich Blackberry (Rubus spp.) by-Product Extract by Freeze-Drying. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 84, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Boch, K.; Schieber, A. Influence of Copigmentation on the Stability of Spray Dried Anthocyanins from Blackberry. LWT 2017, 75, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, E.N.; Molina, A.K.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Heleno, S.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Stojković, D.; Soković, M.; et al. Anthocyanins from Rubus fruticosus L. and Morus nigra L. Applied as Food Colorants: A Natural Alternative. Plants 2021, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.S.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Costa, S.C.; Madrona, G.S. Antioxidant Compounds from Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) Pomace: Microencapsulation by Spray-Dryer and PH Stability Evaluation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Carvalho, A.M.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Cámara, M.; Morales, R.; Tardío, J. Wild Edible Fruits as a Potential Source of Phytochemicals with Capacity to Inhibit Lipid Peroxidation. Eur. J. Lipid. Sci. Technol. 2013, 115, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska, A.M.; Oleszek, W.; Braca, A. Quali-Quantitative Analyses of Flavonoids of Morus nigra L. and Morus alba L. (Moraceae) Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3377–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada-Bellido, E.; Ferreiro-González, M.; Carrera, C.; Palma, M.; Barroso, C.G.; Barbero, G.F. Optimization of the Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Anthocyanins and Total Phenolic Compounds in Mulberry (Morus nigra) Pulp. Food Chem. 2017, 219, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, E.M.; Yusof, N.; Chatzifragkou, A.; Charalampopoulos, D. Stability Enhancement of Anthocyanins from Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.) Pomace through Intermolecular Copigmentation. Molecules 2022, 27, 5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliaño González, M.J.; Carrera, C.; Barbero, G.F.; Palma, M. A Comparison Study between Ultrasound–Assisted and Enzyme–Assisted Extraction of Anthocyanins from Blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum L.). Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, A.K.; Vega, E.N.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Heleno, S.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Kostić, M.; Soković, M.; et al. Promising Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Food Colourants from Lonicera caerulea L. var. Kamtschatica. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celli, G.B.; Ghanem, A.; Brooks, M.S.-L. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Anthocyanins from Haskap Berries (Lonicera caerulea L.) Using Response Surface Methodology. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 27, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.-J.; Ko, M.-J.; Chung, M.-S. Anthocyanin Structure and PH Dependent Extraction Characteristics from Blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum) and Chokeberries (Aronia melanocarpa) in Subcritical Water State. Foods 2021, 10, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nistor, M.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Frond, A.D.; Stirbu, I.; Socaciu, C.; Pintea, A.; Rugina, D. Comparative Efficiency of Different Solvents for the Anthocyanins Extraction from Chokeberries and Black Carrots, to Preserve Their Antioxidant Activity. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, V.; Vijaeeswarri, J.; Lakshmi, J.A. Effective Natural Dye Extraction from Different Plant Materials Using Ultrasound. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Breksa, A.P., III; Pan, Z.; Ma, H.; Mchugh, T.H. Storage Stability of Sterilized Liquid Extracts from Pomegranate Peel. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C765–C772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykes, L.; Rooney, W.L.; Rooney, L.W. Evaluation of Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity of Black Sorghum Hybrids. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 58, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Gullón, P.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, M.; de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, R.M.; Manzoor, S.; Caceres, J.O. Lycopene: A Review of Chemical and Biological Activity Related to Beneficial Health Effects. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2013; Volume 40, pp. 383–426. [Google Scholar]

- Rizk, E.M.; El-Kady, A.T.; El-Bialy, A.R. Charactrization of Carotenoids (Lyco-Red) Extracted from Tomato Peels and Its Uses as Natural Colorants and Antioxidants of Ice Cream. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2014, 59, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Labarca, V.; Giovagnoli-Vicuña, C.; Cañas-Sarazúa, R. Optimization of Extraction Yield, Flavonoids and Lycopene from Tomato Pulp by High Hydrostatic Pressure-Assisted Extraction. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.H.Y.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Liceaga, A.M.; San Martín-González, M.F. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Lycopene in Tomato Peels: Effect of Extraction Conditions on All-Trans and Cis-Isomer Yields. LWT 2015, 62, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Lima, R.; Nunes, I.L.; Block, J.M. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Carotenoids from Guava’s Pulp and Waste Powders. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeid, A.; Eun, J.B.; Sagor, S.A.; Rahman, A.; Akter, M.S.; Ahmed, M. Effects of Extraction and Purification Methods on Degradation Kinetics and Stability of Lycopene from Watermelon under Storage Conditions. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, C2630–C2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, L.; Comani, F.; Stingone, C.; Vitelli, R.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M.; Sandei, L. Evaluation of Lycopene Content in Industrial Tomato Derivatives for the Development of Products with Particular Nutraceutical and Health-Functional Properties. Acta Hortic. 2022, 1351, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frandsen, R.J.N.; Khorsand-Jamal, P.; Kongstad, K.T.; Nafisi, M.; Kannangara, R.M.; Staerk, D.; Okkels, F.T.; Binderup, K.; Madsen, B.; Møller, B.L.; et al. Heterologous Production of the Widely Used Natural Food Colorant Carminic Acid in Aspergillus Nidulans. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.C.V.; Dionisio, A.P.; de Abreu, F.A.P.; da Silva, G.S.; Junior, R.D.L.; Magalhães, H.C.R.; dos Santos Garruti, D.; da Silva Araújo, I.M.; Artur, A.G.; Taniguchi, C.A.K.; et al. Microfiltered Red–Purple Pitaya Colorant: UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MSE-Based Metabolic Profile and Its Potential Application as a Natural Food Ingredient. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Demir, E.; Aydogdu, N.; Zare, N.; Karimi, F.; Kandomal, S.M.; Rokni, H.; Ghasemi, Y. Recent Advantages in Electrochemical Monitoring for the Analysis of Amaranth and Carminic Acid as Food Color. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 163, 112929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-evaluation of Anthocyanins (E 163) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, A.; Appelhagen, I.; Martin, C. Natural Blues: Structure Meets Function in Anthocyanins. Plants 2021, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, H. Extraction Characteristics and Optimal Parameters of Anthocyanin from Blueberry Powder under Microwave-Assisted Extraction Conditions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 104, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazmiño-Durán, E.A.; Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E.; Glória, M.B.A. Anthocyanins from Oxalis triangularis as Potential Food Colorants. Food Chem. 2001, 75, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadilova, E.; Stintzing, F.C.; Carle, R. Anthocyanins, Colour and Antioxidant Properties of Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) and Violet Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Peel Extracts. Z. Naturforsch. C. J. Biosci. 2006, 61, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dranca, F.; Oroian, M. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Total Monomeric Anthocyanin (TMA) and Total Phenolic Content (TPC) from Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) Peel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 31, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarabandi, K.; Jafari, S.M.; Mahoonak, A.S.; Mohammadi, A. Application of Gum Arabic and Maltodextrin for Encapsulation of Eggplant Peel Extract as a Natural Antioxidant and Color Source. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella-Osuna, D.E.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A.; Ruíz-Cruz, S.; Márquez-Ríos, E.; Ornelas-Paz, J.d.J.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Ocaño-Higuera, V.M.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Estrada-Alvarado, M.I.; Cira-Chávez, L.A. Nanoencapsulation of Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) Peel Extract in Electrospun Gelatin Nanofiber: Preparation, Characterization, and In Vitro Release. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.B.L.; Lim, Y.Y.; Lee, S.M. Rhoeo spathacea (Swartz) Stearn Leaves, a Potential Natural Food Colorant. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nontasan, S.; Moongngarm, A.; Deeseenthum, S. Application of Functional Colorant Prepared from Black Rice Bran in Yogurt. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 2, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, E.N.; García-Herrera, P.; Ciudad-Mulero, M.; Dias, M.I.; Matallana-González, M.C.; Cámara, M.; Tardío, J.; Molina, M.; Pinela, J.; Pires, T.C.; et al. Wild Sweet Cherry, Strawberry and Bilberry as Underestimated Sources of Natural Colorants and Bioactive Compounds with Functional Properties. Food. Chem. 2023, 414, 135669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Vives, C.; García-Herrera, P.; Sánchez-Mata, M.C.; Cámara-Hurtado, R.M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.L.; Aceituno, L.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Días, M.I.; Barros, L.; Morales, P. Wild Fruits of Crataegus monogyna Jacq. and Sorbus aria (L.) Crantz: From Traditional Foods to Innovative Sources of Pigments and Antioxidant Ingredients for Food Products. Foods 2023, 12, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Erythrosine (E 127) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, N.; Puértolas, E.; Condón, S.; Raso, J.; Alvarez, I. Enhancement of the Extraction of Betanine from Red Beetroot by Pulsed Electric Fields. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardelli, C.; Benucci, I.; Mazzocchi, C.; Esti, M. A Novel Process for the Recovery of Betalains from Unsold Red Beets by Low-Temperature Enzyme-Assisted Extraction. Foods 2021, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roriz, C.L.; Barros, L.; Prieto, M.A.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Floral Parts of Gomphrena globosa L. as a Novel Alternative Source of Betacyanins: Optimization of the Extraction Using Response Surface Methodology. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roriz, C.L.; Barros, L.; Prieto, M.A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Modern Extraction Techniques Optimized to Extract Betacyanins from Gomphrena globosa L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 105, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo-Bastante, M.J.; Hurtado, N.; Heredia, F.J. Potential Use of New Colombian Sources of Betalains. Colorimetric Study of Red Prickly Pear (Opuntia dillenii) Extracts under Different Technological Conditions. Food Res. Int. 2015, 71, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M.C.; Carriazo, J.G.; Iturriaga, L.; Osorio, C.; Nazareno, M.A. Encapsulating Betalains from Opuntia ficus-Indica Fruits by Ionic Gelation: Pigment Chemical Stability during Storage of Beads. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obón, J.M.; Castellar, M.R.; Alacid, M.; Fernández-López, J.A. Production of a Red–Purple Food Colorant from Opuntia Stricta Fruits by Spray Drying and Its Application in Food Model Systems. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, M.; Barba, F.J.; Grimi, N.; Mhemdi, H.; Koubaa, W.; Boussetta, N.; Vorobiev, E. Recovery of Colorants from Red Prickly Pear Peels and Pulps Enhanced by Pulsed Electric Field and Ultrasound. Inn. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, N.; Jaime-Fonseca, M.R.; San Martin-Martinez, E.; Zepeda, L.G. Extraction, Stability, and Separation of Betalains from Opuntia joconostle cv. Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11995–12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Reconsideration of the Temporary ADI and Refined Exposure Assessment for Sunset Yellow FCF (E 110). EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation Tartrazine (E 102). EFSA J. 2009, 7, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Summary of Color Additives for Use in the United States in Foods, Drugs, Cosmetics, and Medical Devices. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/industry/color-additive-inventories/summary-color-additives-use-united-states-foods-drugs-cosmetics-and-medical-devices (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Coelho, T.L.S.; Silva, D.S.N.; dos Santos Junior, J.M.; Dantas, C.; de Araujo Nogueira, R.; Lopes Júnior, C.A.; Vieira, E.C. Multivariate Optimization and Comparison between Conventional Extraction (CE) and Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction (UAE) of Carotenoid Extraction from Cashew Apple. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 84, 105980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Prá, V.; Soares, J.F.; Monego, D.L.; Vendruscolo, R.G.; Freire, D.M.G.; Alexandri, M.; Koutinas, A.; Wagner, R.; Mazutti, M.A.; da Rosa, M.B. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Palm (Elaeis guineensis) Pressed Fiber Using Different Compressed Fluids. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 112, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, G.L.; Cuevas, M.S.; Capellini, M.C.; Crevellin, E.J.; de Moraes, L.A.B.; Rodrigues, C.E. da C. Extraction of Carotenoid-Rich Palm Pressed Fiber Oil Using Mixtures of Hydrocarbons and Short Chain Alcohols. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuyen, H.V.; Roach, P.D.; Golding, J.B.; Parks, S.E.; Nguyen, M.H. Optimisation of Extraction Conditions for Recovering Carotenoids and Antioxidant Capacity from Gac Peel Using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuyen, H.V.; Nguyen, M.H.; Roach, P.D.; Golding, J.B.; Parks, S.E. Microwave-Assisted Extraction and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Recovering Carotenoids from Gac Peel and Their Effects on Antioxidant Capacity of the Extracts. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.S.; Kar, A.; Dash, S.; Dash, S.K. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of β-Carotene from Ripe Bitter Melon Pericarp. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, B.-M.; Morales, P.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Sánchez-Mata, M.-C.; Cámara, M.; Díez-Marqués, C.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Molina, M.; Tardío, J. Valorization of Wild Strawberry-Tree Fruits (Arbutus unedo L.) through Nutritional Assessment and Natural Production Data. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Camargo, A.d.P.; Gutiérrez, L.-F.; Vargas, S.M.; Martinez-Correa, H.A.; Parada-Alfonso, F.; Narváez-Cuenca, C.-E. Valorisation of Mango Peel: Proximate Composition, Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Carotenoids, and Application as an Antioxidant Additive for an Edible Oil. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 152, 104574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mendoza, M.P.; Paula, J.T.; Paviani, L.C.; Cabral, F.A.; Martinez-Correa, H.A. Extracts from Mango Peel By-Product Obtained by Supercritical CO2 and Pressurized Solvent Processes. LWT 2015, 62, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobinaitė, R.; Kraujalis, P.; Tamkutė, L.; Urbonavičienė, D.; Viškelis, P.; Venskutonis, P.R. Recovery of Bioactive Substances from Rowanberry Pomace by Consecutive Extraction with Supercritical Carbon Dioxide and Pressurized Solvents. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 85, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, K.; Framboisier, X.; Frochot, C.; Vanderesse, R.; Barth, D.; Kalthoum-Cherif, J.; Blanchard, F.; Guiavarc’h, Y. Response Surface Methodology Applied to Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) of Carotenoids from Persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.). Food Chem. 2016, 208, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez Díaz, L.; Dorta, E.; Maher, S.; Morales, P.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Cámara, M.; Sánchez-Mata, M.-C. Potential Nutrition and Health Claims in Deastringed Persimmon Fruits (Diospyros kaki L.), Variety ‘Rojo Brillante’, PDO ’Ribera Del Xúquer’. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Gharras, H.; Hasib, A.; Jaouad, A.; El-bouadili, A.; Schoefs, B. Stability of Vacuolar Betaxanthin Pigments in Juices from Moroccan Yellow Opuntia Ficus Indica Fruits. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-López, J.A.; Roca, M.J.; Angosto, J.M.; Obón, J.M. Betaxanthin-Rich Extract from Cactus Pear Fruits as Yellow Water-Soluble Colorant with Potential Application in Foods. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otálora, M.C.; Wilches-Torres, A.; Gómez Castaño, J.A. Microencapsulation of Betaxanthin Pigments from Pitahaya (Hylocereus megalanthus) By-Products: Characterization, Food Application, Stability, and In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Foods 2023, 12, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciurlia, L.; Bleve, M.; Rescio, L. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Co-Extraction of Tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) and Hazelnuts (Corylus avellana L.): A New Procedure in Obtaining a Source of Natural Lycopene. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2009, 49, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Viera, I.; Roca, M. Study of the Authentic Composition of the Novel Green Foods: Food Colorants and Coloring Foods. Food Rese Int. 2023, 170, 112974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Green S (E 142) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Re-evaluation of Copper Complexes of Chlorophylls (E 141(i)) and Chlorophyllins (E 141(Ii)) as Food Additives. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Changan, S.; Tomar, M.; Prajapati, U.; Saurabh, V.; Hasan, M.; Sasi, M.; Maheshwari, C.; Singh, S.; Dhumal, S.; et al. Custard Apple (Annona squamosa L.) Leaves: Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, and Health-Promoting Biological Activities. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiekh, K.A.; Olatunde, O.O.; Zhang, B.; Huda, N.; Benjakul, S. Pulsed Electric Field Assisted Process for Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Custard Apple (Annona squamosa) Leaves. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Vega, R.; Rodríguez-Roque, M.J.; Elez-Martínez, P.; Martín-Belloso, O. Impact of Critical High-intensity Pulsed Electric Field Processing Parameters on Oxidative Enzymes and Color of Broccoli Juice. J. Food Process Preserv. 2020, 44, e14362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-H.; Wang, L.-H.; Zeng, X.-A.; Han, Z.; Wang, M.-S. Effect of Pulsed Electric Fields (PEFs) on the Pigments Extracted from Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). Inn. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 43, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamwonglumlert, L.; Devahastin, S.; Chiewchan, N. Molecular Structure, Stability and Cytotoxicity of Natural Green Colorants Produced from Centella Asiatica L. Leaves Treated by Steaming and Metal Complexations. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.-R.; Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, Y.H. Characterization and Storage Stability of Chlorophylls Microencapsulated in Different Combination of Gum Arabic and Maltodextrin. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarry, I.E.; Wang, Z.; Cai, T.; Wu, Z.; Kan, J.; Chen, K. Utilization of Different Carrier Agents for Chlorophyll Encapsulation: Characterization and Kinetic Stability Study. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidana Gamage, G.C.; Lim, Y.Y.; Choo, W.S. Anthocyanins from Clitoria ternatea Flower: Biosynthesis, Extraction, Stability, Antioxidant Activity, and Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 792303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Opinion on the Re-Evaluation of Brilliant Blue FCF (E 133) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1853. [CrossRef]

- Younes, M.; Aquilina, G.; Degen, G.; Engel, K.; Fowler, P.; Frutos Fernandez, M.J.; Fürst, P.; Gürtler, R.; Husøy, T.; Manco, M.; et al. Follow-up of the Re-evaluation of Indigo Carmine (E 132) as a Food Additive. EFSA J. 2023, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneechot, O.; Hahor, W.; Thongprajukaew, K.; Nuntapong, N.; Bubaka, S. A Natural Blue Colorant from Butterfly Pea (Clitoria ternatea) Petals for Traditional Rice Cooking. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loñez, H.E.; Banwa, T.P. Butterfly Pea (Clitoria ternatea): A Natural Colorant for Soft Candy (Gummy Candy). Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 14, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockowandt, L.; Pinela, J.; Roriz, C.L.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Barros, L.; Bredol, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical Features and Bioactivities of Cornflower (Centaurea cyanus L.) Capitula: The Blue Flowers and the Unexplored Non-Edible Part. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 128, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayekpam, C.; Hamsavi, G.K.; Raghavarao, K.S. Efficient Extraction of Food Grade Natural Blue Colorant from Dry Biomass of Spirulina Platensis Using Eco-Friendly Methods. Food Bioprod. Process 2021, 129, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiklahan, R.; Chirasuwan, N.; Bunnag, B. Stability of Phycocyanin Extracted from Spirulina sp.: Influence of Temperature, PH and Preservatives. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo Paes Barretto, F.J.; Clemente, H.A.; Santana, A.L.B.D.; da Silva Vasconcelo, M.A. Stability of Encapsulated and Non-Encapsulated Anthocyanin in Yogurt Produced with Natural Dye Obtained from Solanum melongena L. Bark. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2020, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, F.; Condurache, N.N.; Horincar, G.; Constantin, O.E.; Turturică, M.; Stănciuc, N.; Aprodu, I.; Croitoru, C.; Râpeanu, G. Value-Added Crackers Enriched with Red Onion Skin Anthocyanins Entrapped in Different Combinations of Wall Materials. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, S.; Pasli, A.A.; Ozcelik, B.; Van Camp, J.; capanoglu, e. colour retention, anthocyanin stability and antioxidant capacity in black carrot (daucus carota) jams and marmalades: Effect of processing, storage conditions and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. j. funct. foods 2015, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horincar, G.; Enachi, E.; Bolea, C.; Râpeanu, G.; Aprodu, I. Value-Added Lager Beer Enriched with Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) Peel Extract. Molecules 2020, 25, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Wani, A.A.; Singh, D.P.; Sogi, D.S. Shelf Life Enhancement of Butter, Ice-Cream, and Mayonnaise by Addition of Lycopene. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 1217–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálora, M.C.; de Jesús Barbosa, H.; Perilla, J.E.; Osorio, C.; Nazareno, M.A. Encapsulated Betalains (Opuntia ficus-Indica) as Natural Colorants. Case Study: Gummy Candies. LWT 2019, 103, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roriz, C.L.; Heleno, S.A.; Carocho, M.; Rodrigues, P.; Pinela, J.; Dias, M.I.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Morales, P.; Barros, L.; et al. Betacyanins from Gomphrena globosa L. Flowers: Incorporation in Cookies as Natural Colouring Agents. Food Chem. 2020, 329, 127178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roriz, C.L.; Carocho, M.; Alves, M.J.; Rodrigues, P.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Heleno, S.A.; Barros, L. Betacyanins Obtained from Alternative Novel Sources as Natural Food Colorant Additives: Incorporated in Savory and Sweet Food Products. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 8775–8784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajila, C.M.; Aalami, M.; Leelavathi, K.; Rao, U.J.S.P. Mango Peel Powder: A Potential Source of Antioxidant and Dietary Fiber in Macaroni Preparations. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, D.G.; Durmaz, Y.; Konar, N.; Toker, O.S.; Palabiyik, I.; Tasan, M. Using Encapsulated Nannochloropsis oculata in White Chocolate as Coloring Agent. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 3077–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palabiyik, I.; Durmaz, Y.; Öner, B.; Toker, O.S.; Coksari, G.; Konar, N.; Tamtürk, F. Using Spray-Dried Microalgae as a Natural Coloring Agent in Chewing Gum: Effects on Color, Sensory, and Textural Properties. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkallah, M.; Dammak, M.; Louati, I.; Hentati, F.; Hadrich, B.; Mechichi, T.; Ayadi, M.A.; Fendri, I.; Attia, H.; Abdelkafi, S. Effect of Spirulina Platensis Fortification on Physicochemical, Textural, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties of Yogurt during Fermentation and Storage. LWT 2017, 84, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajila, C.M.; Leelavathi, K.; Rao, U.J.S.P. Improvement of Dietary Fiber Content and Antioxidant Properties in Soft Dough Biscuits with the Incorporation of Mango Peel Powder. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Color | Origin | Scientific Name | Chemical Compound | Isolation | E Number | CFR Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | Butterfly pea flower extract | Clitoria ternatea L. | Anthocyanins | Aqueous extraction | NA | 73.69 |

| Blue-green | Spirulina extract | Arthrospira platensis | Phycocyanins | NA | 73.530 | |

| Green | Edible plant material, grass, lucerne and nettle extract | Gramineae, Medicago sativa L., Urtica dioica L. | Chlorophylls | Solvent extraction | E140i Cl natural green 3; magnesium chlorophyll; magnesium phaeophytin | |

| Green-blue | Edible plant material, grass, lucerne and nettle extract | Gramineae, Medicago sativa L., Urtica dioica L. | Chlorophyllins | Solvent extract and saponification | E140ii Cl natural green 5; sodium chlorophyllin; potassium chlorophyllin | |

| Green-blue | Edible plant material, grass, lucerne and nettle extract | Gramineae, Medicago sativa L., Urtica dioica L. | Copper complex of chlorophylls | Solvent extraction and addition of a salt of copper | E141i Cl natural green 3; copper chlorophyll; copper phaeophytin | |

| Green-blue | EU: Edible plant material, grass, lucerne and nettle. US: alfalfa extract | US: Medicago sativa L. | Copper complex of chlorophylls | Solvent extract, saponification, and addition of a salt of copper | E141 (ii) CI Natural Green 5; Sodium Copper Chlorophyllin; Potassium Copper Chlorophyllin | 73.125 |

| Yellow | Turmeric extract | Curcuma longa L. | Curcumin | Solvent extraction | E100 Cl natural yellow 3, turmeric yellow, diferoyl methane | 73.600 |

| Turmeric oleoresin | Curcuma longa L. | Curcumin | Extraction with exact solvents | NA | 73.615 | |

| Yellow-orange | Edible plants, carrots, vegetable oils, grass, alfalfa, and nettle extract | Daucus carota L. | Carotenoid—Beta-carotene | Solvent extraction | E160a (ii) Cl food orange 5 | 73.95 |

| Yellow-orange | Algae extract | Dunaliella salina Teod. | Carotenoid—Beta-carotene | Essential oil extraction | E160a (iv) Cl Food orange 5 | |

| Yellow-brown | Edible fruits and plants, grass, lucerne and African marigold extract | African marigold: Tagetes erecta L. | Carotenoids–Lutein | Solvent extraction | E161b Lutein; mixed carotenoids; xanthophylls | |

| Red-brown | Annatto tree seeds outer coating extract | Bixa orellana L. | Carotenoid–bixin | Solvent extraction | E160b (i) Annatto; bixin; norbixin; Cl natural orange 4 | 73.30 |

| Annatto tree seeds outer coating extract | Bixa orellana L. | Carotenoid–bixin | Alkali extraction | E160b (ii) Cl natural orange 4 | ||

| Annatto tree seeds outer coating extract | Bixa orellana L. | Carotenoid–bixin | Vegetal oil extraction | E160b (ii) Cl natural orange 4 | ||

| Yellow-orange | Carrot oil | Daucus carota L. | Carotenoid | Solvent extraction | NA | 73.300 |

| Yellow-orange | Dried stigma powder | Crocus sativus L. | Carotenoid–crocin | Dry grinding | NA | 73.500 |

| Red | Ground dried paprika | Capsicum annuum L. | Carotenoid–capsanthin and capsorubin | Dry grinding | NA | 73.340 |

| Red | Paprika oleoresin | Capsicum annuum L. | Carotenoid–capsanthin and capsorubin | Solvent extraction | E160c | 73.345 |

| Red | Red tomatoes extract | Lycopersicon esculentum L. | Lycopene | Solvent extraction | E160d (ii) Natural yellow 27 | 73.585 |

| Red beets roots extract | Beta vulgaris L. var. Rubra | Betalaine | Pressing, aqueous extraction or dehydrating | E162 Beet red | 73.40 | |

| Red-purple | Grape or black carrot extract | Vitis vinifera L., Daucus carota L. | Anthocyanin | Aqueous extraction | 163 | 73.169 |

| Grape skin extract | Vitis vinifera L. | Anthocyanin–enocianina | Aqueous extraction | 163 | 73.170 |

| Pigment | Natural Source | Pigment Content in Extract | Extraction Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pink color | ||||

| Betacyanins | Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) | - | Extraction through pulsed electric fields (PEFs) followed by a mechanical pressing. Parameters for the electric field: - strength: 0–9 kV/cm - number of pulses: 5–100 Parameters for the mechanical pressing process: - pH: 3.0–6.5 - temperature: 10–60 °C - pressure of press: 0–14 kg/cm2 The best conditions: 5 pulses at 7 kV/cm for PEFs followed by mechanical pressing at 10 kg/cm2 for 35 min with an extracting medium with pH 3.5 and at 30 °C. | [113] |

| 14.67 mg betacyanins/L/U | Enzymatic extraction, including the evaluation of the following parameters: - total dosage of the acetate buffer containing the multi-component enzymatic mix: 10–50 U/g - temperature: 25 or 45 °C - time: 0–5 h - pH: 5.5 - ratio s/L: 1/15 The best extraction conditions: 25 U/g of total dose enzymatic mix, 25 °C and 240 min were the best conditions. | [114] | ||

| Bracts and bracelets (Gomphrena globosa L.) | 45 mg/g, dw | Extraction through maceration with different conditions of time, temperature, water–ethanol proportion, and s/L ratio. The best extraction conditions: 0% of ethanol, 5 g/L of s/L ratio, and 25 °C for 165 min. | [115] | |

| 39.6 mg/g, dw | Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE). The optimal processing conditions: 8 min; 60 °C; 0% ethanol content; and solid/liquid ratio of 5 g/L. | [116] | ||

| 46.9 mg/g, dw | Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE). The optimal processing conditions: 22 min; 500 W; 0% ethanol content; and solid/liquid ratio of 5 g/L. | [116] | ||

| Red prickly pear (Opuntia dillenii (Ker Gawl.) Haw.) | - | Extraction through maceration for 24 h at 10 °C with methanol:water (60:40) as solvent. The best extraction conditions: At room temperature and acid pH the extract changed to a yellowish color; however, at 4 °C, any significant change in the color parameters was evidenced despite the pH value, maintaining the initial red color and the betalain content. | [117] | |

| Cactus fruit (Opuntia ficus indica L. Mill) pulp | - | Extraction by maceration for 5 min with 0.1 M phosphate and 0.05 M citric acid pH 5 buffer as extraction solvent. The best storage conditions: to encapsulate the extract with calcium alginate at 34.6 RH at 25 °C. | [118] | |

| Cactus fruit (Opuntia stricta (Haw.) Haw.) | 357 mg betain /100 g powder | Spray dried. The optimum conditions of spray drying were 160 °C, 0.72 L/h and 0.47 m3/h. | [119] | |

| Cactus fruit (Opuntia stricta (Haw.) Haw.) Peels and pulp by-products | 60 mg/100 g, fw | Extraction through electric fields (PEFs) (voltages of 8, 13.3 and 20 kV/cm and from 50 to 300 pulses). The optimal conditions: 50 pulses at 20 kV/cm were the best conditions | [120] | |

| 50 mg/100 g fruit, fw | Extraction through ultrasound (400 W and 100% of amplitude for 5, 10 and 15 min). The optimal conditions: 15 min was determined as the best time. | [120] | ||

| Prickly pear fruit (Opuntia Joconostle Cv) | 92 mg of betacyanin/100 g of fruit | Different extraction parameters: - time: 10–30 min - temperature: 5–30 °C - solvents: water; methanol-water (4–80%, v/v); and ethanol-water (4–80%, v/v). The best extraction conditions: 15 °C for 10 min with methanol-water (20:80) as solvent | [121] | |

| Pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus (F.A.C. Weber) Britton & Rose) | - | Extraction through maceration at 4 °C for 45 min at 150 rpm and a s/L ratio of 2 mg/mL. | [98] | |

| Pigment | Natural Source | Pigment Content | Extraction Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue color | ||||

| Anthocyanins | Butterfly pea (Clitoria Ternatea L.) flowers | 4.48 mg cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent/100 g of powder dw | Butterfly pea petals were cleaned, dried and ground to a fine powder | [154] |

| Flowers of Centaurea cyanus L. | 27 µg of anthocyanins/g of extract | Maceration extraction: - solvent: methanol/water: 80:20, v/v - temperature: 25 °C - agitation: 150 rpm - time: 1 h | [156] | |

| Phycocyanin | Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) | 47.68 of C-phycocyanin/g (dw) 34.18 mg of A-phycocyanin/g (dw). | Extraction by using silver nanoparticles: - nanoparticles: silver, gold and aluminum oxide - nanoparticle concentration: 0–25 µg/mL - solvent: 0.1 M phosphate buffer and distilled water - salt concentration: 0–25 mg/mL - PEG concentration: 0–30% w/w - time: 120–200 min - temperature: 2–35 °C The best conditions were 10 µg/mL of silver nanoparticles, 3 mg/mL of salt, 10% of PEG, phosphate buffer at 35 °C for 160 min | [157] |

| Food Color | Natural Colorant | Food Matrix | Natural Sources | Main Food Characteristics: Color and Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red-purple | Anthocyanins | Yogurt | Black rice bran extract | Pink color with 0.2% (L*: 80.20, C*: 9.67, h: 18.34) and purplish pink with 0.6%, the highest percentage added (L*: 68.42, C*: 15.23, h: 8.73) | [109] |

| Yogurt | Red onion by-products | Time zero: 0.05 mg cya-3-gluE/g (L*: 75.27, a*: 11.20, b*: 9.55) After 4 weeks of storage 0.039 mg cya-3-gluE/g (L*: 75.19, a*: 11.35, b*: 9.75) | [53] | ||

| Yogurt | Eggplant | Color parameters of the yogurt with 1% of encapsulated extract: L*: 83.74, a*: 3.96 b*: 8.18. | [159] | ||

| Bakery products | Onion skin | Color parameters of the extracts: L*: 22.56, a*: 20.84, b*: −0.78. | [160] | ||

| Marmalade | Black carrot | Thermal processing caused a loss of anthocyanins (79.2–89.5%) | [161] | ||

| Red beer | Eggplant peel extract | Color parameters: L*: 74.67, a*: 9.86, b*: 21.76 | [162] | ||

| Carotenoids (lycopene) | Butter | Tomato skin | Extract concentration: 20 mg/kg Color parameters, at initial time: L*: 48.78, a*: 2.36, b*: 14.17 Color parameters at 4 months of storage at 4–6 °C: L*: 48.37, a*: 2.25, b*: 14.18 | [163] | |

| Mayonnaise | Tomato skin | Extract concentration: 50 mg/kg Color parameters, at initial time: L*: 55.82, a*: 10.32, b*: 19.95 Color parameters at 4 months of storage at 4–6 °C: L*: 53.66, a*: 9.64, b*: 19.10 | [163] | ||

| Ice cream | Tomato skin | Extract concentration: 70 mg/kg Color parameters, at initial time: L*: 84.41, a*: 11.56, b*: 28.59 Color parameters at 4 months of storage at −25 °C: 83.97, a*: 11.16, b*: 21.29 | [163] | ||

| Ice cream | Tomato peel | The ice cream prepared with 3% of extract obtained the highest score in all the parameters of the sensorial analysis | [91] | ||

| Pink | Betalains | Gummy candies | Cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica L. Mill.) fruit pulp | High stability of the color in the gummy candies were observed after 30 days of storage al 4 °C | [164] |

| Yogurt | Pitaya | The yogurts with 0.5% and 2% of the colorant were statistically similar to the commercial yogurts with beetroot and carmine colorants, respectively | [98] | ||

| Cookies | Gomphrena globose L. | Color parameters of samples with the lyophilized extract: L*: 56.3, a*: 22.1, b*: 8.0 Color parameters of samples with the spray dried extract: L*: 56.0, a*: 25.5, b*: 4.3 | [165] | ||

| Ice cream | Gomphrena globose L. | Color parameters: L*: 86, a*: 8, b*: 2.4 | [166] | ||

| Tagliatelle pasta | Flowers of Amaranthus caudatus | Color parameters: L*: 62, a*: 17, b*: 8 | [166] | ||

| Meringue cookies | Red-fleshed pitaya peels | Color parameters: L*: 79.6, a*: 14.5, b*: 1.24 | [166] | ||

| Yellow-Orange | Carotenoids | Dough biscuits | Mango peel | Color parameters of product with 20% of mango peel: L*: 52.90, a*: 7.71, b*: 22.02 | [167] |

| Macaroni | Mango peel | - | [167] | ||

| Green | Chlorophylls | Syrup | Centella asiatica L. | The syrups with the extracts treated with zinc and copper were stable and presented minimum change in color, mostly an increase in the h* value. | [148] |

| Bread | Centella asiatica L. | The bread with the extract treated with zinc presented a yellow–green color, while the one with the extract treated with copper presented a green color. All of them changed significantly after 7 days | [148] | ||

| White chocolate | Nannochloropsis oculata D.J. Hibberd | Samples with the encapsulated extract presented a higher quantity of chlorophylls. However, the samples with free extract presented a better stability of the color along the 28 days | [168] | ||

| Chewing gum | Isochrysis galbana Pascher | Samples showed a decrease in hardness as well as in the cohesiveness, which is advantageous for a chewing gum | [169] | ||

| Yogurt | Spirulina | The preparation with 0.25% showed the best acceptability in the sensory analysis | [170] | ||

| Blue | Anthocyanins | Cooked rice | Butterfly pea flowers | The incorporation of 0.6% of extract resulted in better acceptance by consumers | [154] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vega, E.N.; Ciudad-Mulero, M.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Barros, L.; Morales, P. Natural Sources of Food Colorants as Potential Substitutes for Artificial Additives. Foods 2023, 12, 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12224102

Vega EN, Ciudad-Mulero M, Fernández-Ruiz V, Barros L, Morales P. Natural Sources of Food Colorants as Potential Substitutes for Artificial Additives. Foods. 2023; 12(22):4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12224102

Chicago/Turabian StyleVega, Erika N., María Ciudad-Mulero, Virginia Fernández-Ruiz, Lillian Barros, and Patricia Morales. 2023. "Natural Sources of Food Colorants as Potential Substitutes for Artificial Additives" Foods 12, no. 22: 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12224102

APA StyleVega, E. N., Ciudad-Mulero, M., Fernández-Ruiz, V., Barros, L., & Morales, P. (2023). Natural Sources of Food Colorants as Potential Substitutes for Artificial Additives. Foods, 12(22), 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12224102